A brief overview on how to use submarines in War on the Sea to sink ships, as well as how to find and destroy enemy submarines.

Contents

- Submarine and Anti-Submarine Warfare Guide

- Introduction

- Submarine Classes and Armaments

- Surface Ship Classes and Armaments

- Sonar

- Submarine Strategy

- Submarine Attacks

- Escort Evasion

- Anti-Submarine Strategy

- Anti-Submarine Tactics

Introduction

Submarine attacks in War on the Sea can be incredibly powerful, sinking huge amounts of tonnage while risking very little. However, the most effective way to use your submarines isn’t always intuitive, nor is it necessarily obvious how you should go about hunting down your enemy’s submarines. If you’re unfamiliar with WWII era submarine and anti-submarine tactics I hope that this guide can help you get started.

I’ll firstly be covering some basic concepts and historical context, so if you’re already familiar with this information please feel free to scroll down to the actual gameplay tips located below.

Submarine Classes and Armaments

WWII era submarines spent most of their time on the surface, using diesel engines to travel the long distances to their patrol areas and only submerging to attack or evade. While submerged, they used electric batteries for propulsion, and were much, much slower. On the surface, subs were faster than merchants but slower than other warships. Submerged, the subs were slower than everything else by a wide margin.

The main armament of all submarines was the torpedo, spreads of which could be launched while submerged at periscope depth to hopefully catch the enemy unaware. They were also typically armed with a light anti-aircraft gun and a deck gun, which could be used (very rarely) to attack surface targets and in some navies could also fire flak.

The US subs available in the game’s Guadalcanal campaign consist of the Tambor and Gato classes. These were “fleet submarines,” larger than the subs of other navies and designed to keep up with and scout for the surface fleet across the vast distances of the Pacific. The Tambor is distinct from the Gato in that it is very slightly slower, and cannot dive as deep. The succeeding Balao and Tench classes, which can dive even deeper, are modeled in game but are unavailable for the campaign.

In 1942 US subs are armed with the (historically very unreliable) Mark 14 torpedo, which in game will travel ~9000 yards at 30.5 kn. The subs have both passive and active sonar and, very usefully, surface and air radar. Many Japanese ships have excellent passive sonar, so you will want to avoid using the active sonar most of the time or you will give away your presence. By contrast, most Japanese ships have no radar to speak of, so you will be able to use your own with near impunity.

The Japanese subs available in game are the Type B1 and Type B2, which for the purposes of the game are identical. These were even larger than their American counterparts and even featured a catapult launched scout plane that was stored in a compartment on the deck, a feature fully modeled in game.

In 1942 Japanese subs were armed with the excellent Type 95 torpedo, a variant of the famous Type 93 “Long Lance” torpedo used by Japanese destroyers. In game it will travel ~8000 yards at a very fast 46 kn, which gives you somewhat more versatility regarding which targets you can attack and when. Historically, the Type 95 also had a larger warhead than the Mark 14, which I suspect may be modeled in game but don’t know for sure. The Type B1 and B2 subs have comparable active sonar and better passive sonar than American subs, but no air radar.

As mentioned previously, in 1942 the Mark 14 torpedo was notoriously unreliable: it would run too deep, detonate too early or not at all, and in some horrifying cases the gyro would fail and the torpedo would circle around towards the sub that fired it. This is modeled in game as a much higher rate of duds for the Mark 14: in the region of 33% duds vs. around 5% duds for the Type 95. If you’re playing with duds enabled (which you should be, to experience that authentic submarine skipper pain) as the US this will need to be taken into account.

Surface Ship Classes and Armaments

The main type of ship used for anti-submarine warfare in game is the destroyer. Destroyers are extremely fast, maneuverable, equipped with passive and active sonar, and capable of launching patterns of depth charges off their sterns to damage submerged subs. There are many different classes of destroyers in both the Japanese and US navies, but for the purpose of in game ASW all of the destroyers within a given navy are about as capable as the next. One thing to note is that Japanese ships have better passive sonar than US ships, so if you’re playing as the US you will need to be more careful with your subs’ noise levels.

There are a handful of exceptions worth mentioning:

On the US side, Atlanta class light cruisers are also equipped with sonar and depth charges, though their lower speed and larger size relative to destroyers makes them somewhat awkward in an ASW role.

On the Japanese side, The Momi class destroyers, among the oldest and smallest destroyers in the Japanese navy, have neither sonar nor depth charges. The Oyodo class light cruisers are equipped with passive and active sonar, but are only capable of dropping depth charges one at a time off the stern in a much less effective pattern. Amusingly, several classes of Japanese heavy cruiser are also equipped with passive sonar and depth charges, again dropped one at a time. Actually hitting anything with these huge ships and weak patterns is a tall order, but it can be pretty funny. Lastly, Japanese battleships and carriers are equipped with passive sonar, and while they have no depth charges, they will attempt to evade your subs if they detect you.

Sonar

Detecting enemy submarines and avoiding detection for your own subs revolves entirely around sonar, and understanding it is vital to success and survival. There are two types of sonar: passive and active.

Passive sonar essentially just involves sticking microphones into the water and listening for the sounds made by enemy ships: the engines, the sound of turbulence around the hull, and any noise the crew might be making inside. This is limited by contact noise level, the distance from the contact, the local sea conditions, and any masking noise the listening ship may be making.

Active sonar involves making some kind of noise and listening for the echo bouncing off the hulls of enemy ships (this is the high pitched “ping” noise you hear on TV literally every time a submarine is on screen). Active sonar has the advantage of being able to detect contacts that are being perfectly silent, and it allows the listening ship to build a target solution very quickly. It has the disadvantage that it involves continuously making a lot of very loud noise, which will immediately alert any nearby vessels with passive sonar to your presence. What’s worse, active sonar needs to travel all the way to the target and back in order to detect a contact, whereas it only needs to travel as far as the enemy ship in order to be heard via passive sonar. This means that enemy ships can hear your active sonar at a much longer range than you can use it to detect the enemy.

For surface ships this hardly matters: surface ships are so noisy and obvious than any nearby subs almost certainly already know they’re there, and WWII era subs can’t realistically do anything to harm a maneuvering destroyer anyway. There is no harm to turning on the active sonar on your destroyers when hunting for enemy subs. By contrast, a submarine’s best defense is to remain hidden, and turning on the active sonar is a sure way to let everyone know you’re there. This is not recommend unless dodging depth charges is your hobby. Active sonar is limited by distance to contact, the size of the contact (bigger ships reflect more sound), the facing of the contact (a side-on contact will reflect sound waves more strongly), local sea conditions, and again the amount of noise the listening ship is making. Having the seabed close behind a submarine will also make it harder to detect with active sonar, since it’s harder to distinguish the return from the contact vs. the return from the sea floor.

Ships that are traveling faster will make more noise due to louder engines and greater turbulence around the ship’s hull. This will make the ship easier to detect via both passive and active sonar (turbulence helps to reflect active sonar sound waves). Higher speeds will also make the ship’s passive and active sonar less effective, as it will be harder to hear the noise of enemy contacts over the noise the listening ship is making. Both surface ships and submarines also have an area directly behind them called the “baffles,” where they can’t detect anything by either active or passive sonar.

All sonar is affected by the local sea state, which in game is indicated as 0 through 8, with 0 being the calmest seas and 8 being the roughest seas. Rough seas create a lot of ambient noise, which makes listening for enemy contacts much harder. In sea states 0 through 3, submarines can usually be located with relative ease. In sea states 4 and 5 surface ships will need to be going slow and close to pick up a contact. At sea states 6 and above ships will have to be perfectly stationary and directly above an enemy sub in order to hear it, if it’s even possible at all.

If the seas are relatively calm there may also be a thermal layer, which is a depth at which the temperature of the ocean drops sharply. Thermal layers tend to reflect sound waves away from the layer, which makes it harder for ships on opposite sides of the layer to hear each other. Sound waves created above the layer will also tend to bounce between the surface and the layer, which creates a “duct” in which sound waves will travel much farther than they would otherwise. The layer depth, strength, and strength of the duct are available in the menu. A strong layer can help your submarines avoid detection and make getaways in quiet seas where escape would otherwise be impossible.

I also suspect that cavitation may play a roll in sub detection, depending on the fidelity of the WotS sonar model. This is pure conjecture on my part, since it’s not mentioned anywhere in the manual, but cavitation itself seems to be modeled in the game so it seems worth mentioning. Cavitation is when the propeller of the ship is spinning hard enough to turn some of the water around it to gas, and it is extremely loud. You can tell whether or not your subs are cavitating by the presence or absence of bubbles around the propeller. The deeper your sub is, the faster it can go without cavitating. Again, no idea whether noise from cavitation is actually used for passive sonar detection in game, but it can’t hurt to avoid it when possible.

Submarine Strategy

in the campaign, your subs are best used as scouts, convoy raiders, and to pick off any large warships that happen to wander past. Subs cost very few command points and can be deployed in large numbers, so you’ll want to deploy a number of them between the enemy home port and any important objectives in order to intercept convoys. It’s also useful to have a bunch of them positioned around your important fleets, especially your carriers, to detect and harass any enemy surface groups that might otherwise catch you by surprise.

When attacking an enemy surface group, you’ll need to prioritize your targets carefully. You are realistically only going to get one spread of torpedoes away before you have to disengage. This is for two reasons: firstly, as soon as your torpedoes hit anything, the other ships will begin evading, making it very difficult to hit them with any follow up attacks. Secondly, on torpedo impact any escorts will immediately begin making a beeline for the location where you launched the torpedoes from, and it is very much in your best interest not to be there when they arrive.

Targeting destroyers and light cruisers is generally not advisable, given that they are difficult to hit and not worth many command points. If there is only one destroyer guarding a convoy, however, it might be worth trying to knock it out first so that you can reengage the convoy later and attack with no risk of reprisal. If you do manage to successfully get a spread off on a destroyer or light cruiser, it will only take one or two hits to sink it.

Heavy cruisers, battleships, or (the Holy Grail) carriers are much better targets. They’re larger, slower, worth a bunch of command points, and even if you don’t sink them that’s still a lot of firepower out of the fight for the near future. It’s worth giving these a full spread of torpedoes, since depending on the difficulty you’re playing at the largest ships can sometimes eat even a full spread and still stay afloat, especially if you’re using Mark 14’s.

When attacking convoys, it’s best to go for oilers first. Oilers are larger, worth more command points, and no matter how much engineering equipment and supplies the enemy has they won’t be able to upgrade their ports and airfields without any oil. A full oiler is also extremely flammable, understandably, so if you manage to start any kind of fire at all it’s likely to grow into a raging inferno that will take the whole thing down.

I have experimented somewhat with using groups of subs in “wolf pack” attacks. It allows you to really ruin the day of any one particular surface group at the expense of having much less coverage over the wider area. It also requires very careful coordination of your torpedo attacks: if one torpedo spread arrives much earlier than the others, then your other targets will begin maneuvering and those other spreads will likely miss. Personally I prefer the enhanced scouting and reduced micromanagement of using lone subs, but your preferences may vary.

Submarine Attacks

When you first begin an encounter with an enemy surface group, your sub(s) will spawn submerged and likely ahead of the enemy group, in a good position to make a torpedo attack. The very first thing you need to decide is whether you’re going to make an attack at all. Your biggest two concerns are the composition of the surface group and the local sonar conditions. If the surface group is just a few destroyers, it’s probably worth saving your torpedoes for a convoy or large warship.

The best sonar conditions in which to make an attack are during high seas or in the presence of a strong thermal layer, which will make it much easier to make your escape after your attack. Attacking during quiet seas with no thermal layer will nearly guarantee that the enemy escorts will be able to find you, which tends to have a strongly negative effect on your submariners’ life expectancy. Also, if the enemy escorts are going to be within about 2000 or 3000 yards of your sub when you make your attack, it will make it much more difficult to get away. Finally, you should bear in mind that you can only reasonably attack a ship with a constant heading and speed. If your target is maneuvering or changing speed, it’s not worth wasting your torpedoes. If you decide it’s not worth attacking, just set your speed to 0, go to ultra quiet, and start the retreat timer.

Once you’ve decided to make your attack and chosen a target, you need to maneuver into position. Torpedo attacks are most accurate when the torpedoes impact the target side-on with a low gyro angle. This means that you want your sub’s heading to be off by 90 degrees relative to the heading of your target. You also want the torpedoes to run as straight as possible without having to turn very much once they’ve armed. US subs have rear torpedo tubes and can attack while facing away, which makes it easier to begin your escape at the cost of only being able to fire a spread of 4 torpedoes instead of 6. Japanese subs only have forward torpedo tubes and need to be facing their target.

Once you’re in position, kill your speed and wait for your target solution to build up. Your target solution will increase by correctly identifying your target and observing it using your scope, passive sonar, and radar (only if playing as the US: using your radar as the Japanese is not advisable as all US warships will be able to pick up your signal). Active sonar can also help, but you should only turn it on if there are no ships with any passive sonar in the entire surface group, which is very rare. Also, a few Japanese warships do in fact have radar, and you will want to make sure you’re not facing one of them before turning on your radar or your radar signal will give you away.

While waiting for your target solution to build, select how many torpedoes to fire with what spread angle. When playing as the US, the Mark 14 is so unreliable that you’re probably just going to want to go ahead and fire a full spread of six. You’ll thank me when 5 out of those 6 turn out to be duds (yes, this has happened to me. No, I’m still not over it). With Japanese subs you can afford to be more frugal, and throw on maybe one more torpedo than you think you need on the off chance you get a dud.

If you want all your torpedoes to hit the same ship, an angle of 1 degree is best. If you just want to cause as much havoc as possible in a large, crowded convoy, you can crank it all the way up to 10 degrees. If your max firing solution is lower than 99%, usually due to low visibility, you’ll want to increase your angle and add more torpedoes to taste.

Once your solution is as good as it’s going to get, fire your torpedoes once the gyro angle is close to zero (you can see the gyro angle of the current solution by mousing over the torpedo room). Immediately set your depth the the lowest you can go (you can get away with going a bit lower than your test depth) and set a course away from the enemy escorts as fast as you can go. If you’re in a strong duct, you may want to hold off increasing your speed until you’re below the layer to avoid alerting the enemy prematurely. All going to plan, your enemy should be unaware right up until the torpedoes hit them, and you should be long gone by the time the escorts reach your firing position.

The steps to a successful getaway:

- Get as far away as possible as fast as possible.

- Get as deep as possible.

- Face directly away from searching escorts, to minimize active sonar return.

- Hug the seabed if possible, again to avoid active sonar.

- Rig for ultra quiet to stop reloading noise.

- If escorts are nearing your sub despite your efforts, slow to 1 or 2 kn to hopefully avoid passive detection.

- Avoid letting your sub cavitate (again, not sure if this is modeled).

Keep a close eye on the enemy escorts. If they’re still heading towards where you were, you’re still in the clear. If they start heading towards where you are, you have a problem.

Escort Evasion

If the enemy escorts pick you up on their sonar, you’re in serious trouble. Dodging depth charges launched by a ship going 35 kn in a ship going 8-9 kn is a tall order. You want to be as deep as your sub can go, which will give you more time to dodge while the depth charges fall from the surface. Not getting blown out of the water will require a bit of luck, but here’s a method I’ve found that seems to work.

- Go to max speed and line up your heading with the heading of the incoming escort.

- As soon as the depth charges start dropping, turn the rudder fully to port or starboard.

- Pray.

If you survive that pattern of depth charges, the good news is that you’re now in the escort’s baffles, which means they’ve lost contact with you. Reduce your speed to 1-2 kn, turn away from the escort, and if the seas are noisy or there’s a strong layer you might be able to slink away without being reacquired. More likely, the escort will turn around, find you again, and come in for another run, and you’ll need keep dodging depth charges until your pursuers run out.

Japanese destroyers and the Oyodo class normally have 36 depth charges (though some of the early destroyer classes have more or less), enough for two patterns of 15 and one itty bitty pattern of 6. The Japanese heavy cruisers usually have 12 charges, and can only drop 5 at a time, but for some bizarre reason the Takao class has a whopping 60. Dodging twelve runs of 5 charges is easy, but tedious. US destroyers and the Atlanta class, meanwhile, all have 60 depth charges each, enough for four big runs, so buckle up.

Once the escorts run out of depth charges, they’ll keep doing dry runs on your sub. I suppose technically the escorts could just keep following you until either you run out of battery/oxygen and need to surface or sonar conditions change and you can get away, but that would take hours and isn’t modeled in game, so just start the retreat timer.

If you do take any damage from the depth charges, you’re likely screwed. Your repair crew might be able to contain the flooding and let you keep going, but more likely those sections are destroyed and you’re now sinking towards your crush depth. If the seabed is above your crush depth you can try to rest silently on the sea floor, which might give you just that little bit of an edge to confound enemy active sonar. If you should be so lucky, the enemy escorts will just keep circling your last known position ad infinitum, so go ahead and start the retreat timer.

If you’re in deep waters, however, your last desperate measure is to do an emergency blow ballast and surface the ship. At this point you’re essentially as good as sunk. Compared to the hulls of surface ships the pressure hull of a submarine might as well be made out of paper, and even an armed merchant will make short work of you if it catches you on the surface. The best you can hope for is to take a couple of spiteful shots with your deck gun and maybe knock out a turret or two before you go down fighting.

While I scarcely dare mention it, it is possible to exploit your way out of these chases by manipulating the very generous retreat timer system, but where’s the fun in that? Submarine and escort chases are tense and exciting, and you’d essentially be opting out of playing the game you paid for. If you choose to sully your honor in this manner, I’ll let you figure out how to do it on your own. Hopefully Killerfish will revamp the retreat timer system in the future to appease masochists like me.

Anti-Submarine Strategy

In all this talk of sonar and escorts, I’ve neglected to mention probably the biggest threat to submarines: aircraft. WWII era subs spend most of their time on the surface, and it takes a minute or so for them to be able to start diving. This gives aircraft, if not spotted in time, the opportunity to drop bombs on the exposed subs. As such, when you start an encounter between your aircraft and an enemy sub the sub will start on the surface. A direct hit from pretty much any kind of air dropped explosive will blow a submarine’s pressure hull wide open, either sinking the sub outright or forcing it to quickly resurface where it can be strafed to death.

Any time your recon planes spot an enemy sub on the campaign map, you should send a flight or two of bombers after it. Wait until you’re nearly over the top of the sub before starting the encounter, and you’re likely to be able to get your bombs off before it can dive. If you score a hit and don’t get the notification that the sub is sinking, then start circling the area and wait. More likely than not, the sub will eventually be forced to blow ballast and resurface, at which point a few strafing runs will send it back beneath the waves for good. This may take a while, so turn on time compression and be patient.

Any kind of high explosive loadout will work wonders against the unarmored hull of a submarine, provided you land a direct hit. Avengers, however, are especially excellent sub hunters because they have access to rockets and air dropped depth charges. A volley of rockets from a flight of Avengers will turn any surfaced submarine into Swiss cheese, and depth charges will ensure that even a sub that’s able to begin it’s dive won’t escape.

As for escorts, each of your surface groups should have at least two destroyers in its formation to hunt down any attacking enemy subs.

It’s also very useful to establish dedicated ASW patrols, which should consist of two or three destroyers. Your navy’s cheap, outdated destroyers make excellent candidates for these. You should primarily patrol the areas ahead of your important fleets and around where your convoys will be transiting.

Anti-Submarine Tactics

When any of your surface groups (hopefully one of your ASW patrols) begins an encounter with an enemy sub, that sub will start at periscope depth having already launched a spread of torpedoes at your ships. This happens Every. Single. Time. Even if you began the encounter using aircraft, if any of your ships are in the combat area the enemy sub will magically teleport in front of your ships and launch a spread of torpedoes at them. Bear this in mind.

The very first thing you want to do is run the simulation for a few seconds, pause, and then look for the trail of the incoming torpedoes. When you find it, note where the trail is coming from, because that’s where the enemy sub is. Maneuver any of your ships that are being targeted out of the path of the incoming torpedoes, turn on all your active sonar, and send your destroyers that aren’t in danger towards the source of the torpedoes (this is why you always make sure to bring at least two destroyers).

Whether or not you’ll be able to make sonar contact with the enemy sub is largely dependent on the local sonar conditions. In sea states 0-3, you could hear a pin drop inside that sub and it essentially just signed its death warrant by attacking you, in sea states 4-5 you’re going to have your work cut out for you, and in sea state 6 you’ll need to get very lucky and be almost directly over the sub in order to find it. Don’t even bother in states 7 or 8.

Remember: the faster your destroyers are moving, the less effective their sonar will be. You want to rush your destroyers over to where you think the sub is, kill off all your speed, and listen for a few seconds. Experience has caused me to suspect that having your active sonar on interferes with your passive sonar (though I don’t know why this would be) so while you’re listening turn off your active for a few seconds, especially if you’re using Japanese destroyers with their superb passive sonar. If you don’t make contact with the enemy sub, fire your engine back up, move maybe 500 yards or so in a direction you think the sub might have gone, and stop again to listen. Bring your other destroyers into the area and continue this start/stop search pattern until you either find the sub or decide to give up. You need to strike a fine balance here: too slow and the sub will slip away, too fast and you’ll cruise right over the sub without hearing it.

With a little luck, you’ll pick up the contact, and at this point you’ve very nearly got her dead to rights. The AI is not nearly as good at dodging depth charges as you are. Begin lining your destroyers up for depth charge runs. In poor sonar conditions I find that it’s sometimes a good idea to keep one destroyer as a “spotter,” slowly shadowing the submarine so you don’t lose contact while your other destroyers perform depth charge runs. Once you’ve got a destroyer pointed towards the sub and within about 500 yards, use the attack command to start a depth charge run. You could perform the run manually, but honestly it’s kind of a pain and I find the auto attack gets the job done just as well.

Once you’ve managed to damage the enemy sub with your depth charges, it’s all over but the crying. If it doesn’t sink outright, it will be forced to blow ballast and resurface, at which point your destroyers’ guns can rip it to shreds. Do note that the sub is liable to get off a few rounds with it’s deck gun before it sinks, which might knock out something important on your destroyer with a lucky hit, so try to make sure the sub sinks as quickly as possible.

The game is quite big and as a beginner it can be quite overwhelming. I hope this guide can help you get started.

The Factions

You can start a campaign as either the Japanse or the Americans. Both have very interesting elements to their complement of vessels and their starting locations. They are balanced in their difficulty, but require a diffrent type of stratagy. I would recommend reading this first before choosing a faction. A campaing can take an incredible amount of time, especially if you want to use the maximum amount of micro. Here are my thougts on the Factions in the Game.

Japan

The main task of the japanese is to build a level 5 airfield on the island of guadalcanal, wich luckily, is already occupied by a token force. To continue building up your base on the island, your main focus will be supporting your convoys to guadalcanal and securing the waters around the archipellago. It is a more defensive style of gameplay. Expect to invest many hours in patrolling the area and waiting for nightfall to secure a safe passage for your convoys.

They have a wide arrange of fast and strong heavy cruisers. Their battleships, especially the Yamoto, are very strong an versaitaille. (The congo has a very big amount of secondary’s). They do not have a lot of command points at the start, and because many points will be spent on convoys, dont expect to use carriers until mid-game. Their light cruisers at the start of the game are vintage ww1 ships, and wont provide you with a lot of firepower. Their top tier destroyers are a better choise for that task. However these cruisers van withstand a bit more damage. In the mid to late game, new light cruisers will come availible, wich will provide you with a better way of dealing with enemy destroyers. Although the best aspect of the japanese is of course the type 93 torpedo. These never fail to enjoy me. With their inmense range they can play a huge role in any battle. Thats why they have many installed on cruisers and destroyers.

Playstyle: Defence

Pros:

1. The long lance (exelent long range torpedo)

2. Starting with objective secured and many islands already under your control

3. Versaitalle and strong Heavy cruisers and Battleships

Cons:

1. Big focus on guarding convoys

2. A lack of (surface) radar and good sonar on most ships

3. Weak light cruisers

USA

The main goal of the US is to capture Guadalcanal and build a level 5 airfield. So your main focus at first will be to defeat the enemy force (at land and at sea) near and at guadalcanal. The playstyle of the US is aggressive, actively seeking out enemy fleets and disrupting their supply lines to guadalcanal. Due to the fact that your main goal is to eliminate the enemy, you will be commanding bigger fleets, due to less command points being spend on convoy ships (troops can be moved with warships). As you only start with 3 ports, of wich 2 ar very far from your objective, it is very usefull to capture the many ports near guadalcanal to build up a defence perimeter after the capture of your main objective, providing you with air cover and granting spotting oppertunitys by the occupied ports. Most Japanse ports are only garrisoned by a token force.

Their choise of vessels is large and there are many advantages to the American fleet. Their first advantage over the japanese is their more modern navy. This means most vessels have surface radar and a good set of sonars. This will be very helpfull in spotting enemy fleets and will help in engaging enemy’s at large distances or at night. Next in line are their exelent light cruisers. These ships will easily overpower enemy destroyers and light cruisers, providing your heavy ships with protection from the enemey (very effective) torpedo’s. But due to their longe range, always keep on the lookout, even though they are miles away.

Playstyle: Aggressive

Pros:

1. Good radar and sonar

2. Great light cruisers

3. many differerent types of ships

Cons:

1. You have to capture guadalcanal first before you can build up the island.

2. Much of the enemy waters have air cover due to the many Japanese occupied ports (10 in total)

3. Your territory is divided and small (only three ports), causing you to divide your forces

Getting started

Builing a fleet

Your first step is to start builing a fleet. No matter the faction that you have picked. I had a bit of trouble myself finding this out, as there isnt a dedicated button or interface for this. But the creation of a fleet starts as follows:

1. Go to you main port (Rabaul for Japan, New Hebrides for the US)

2. Click on the New Sea icon under the port icon.

3. Now at the bottom of the screen a ship log should pop up.

4. You can scroll through the ships, select the ship that you want to add to your fleet

5. Keep adding ships till you think your task force is complete. Remeber that you will need multiple task forces, so dont put al your ships in one fleet.

Moving your fleets on the map

To move your fleet, select your fleet, and click on course to set a point for your to move to. It is wise to have some fleets patrol a certain area where you think an enemy fleet could be. For this i mostly use a zig zag pattern to cover a area. Recon is the most valuable thing in naval warfare, so make dedicated scout groups if you can.

A simple guide to ship types

Submarines

These ships are the assasins on water (or under water actually). Due to the fact that they start submerged as combat begins, the can sneak up to the enemy fleet or convoy undetected. Their main goal is to snipe big ships and destroy convoy ships. They are also very usefull for scouting, as they have a single scoutplane on board.

Destroyers

Destroyers have 2 functions. They are very good in engaging with enemy subs. They are fast an agile, and can easily position themselves above an enemy sub and dorp their dept charges. They are also the only ship type, besides a few light cruisers, to have depht charges, so using destroyers for convoys is a must since they are otherwise very vurnable to submarines.

Their second function lies in taking out the enemy’s large ships. They often have a lot of torpedo’s on them, and their speed and mobility give them the oppertunity to close distance fast and evade shots of enemy largse ships due to their size.

Light cruisers

These ships are essentially destroyer destroyers. They are fast and have a lot of small guns on board. They will struggle against heavy cruisers due to their low amount of piercing, but they can do effective damage when positioned correctly. Only use these against battleships if the ship has torpedo capabilities and can safely close distance.

Heavy Cruisers

The most versataille of ships. They can engage almost any target (exept subs). But in their versaitility lies their greatest weakness. They are not 100% effective against al. They can take out a destroyer with ease, but multiple destroyers can overrun them. They can engage battleships, but their piercing isnt high enough to pierce the most protected parts. Nevertheless, this will be the ship type you will be using the most.

Battleships

These ships are the monsters of the sea. They can take an absurd amount of damage, and can engage enemy’s from large distances. They are rather slow and are very hard to maneuver. So guard them well from smaller ships, as a couple well placed torpedos can render them useless. They are best used from a safe distance, so dont let them get to close to enemy ships. They are also one of the most expensive, losing one early on can make you lose the entire campaign.

Carriers

These vessels are the most effective on the campaign, where they can deploy numerous aircraft from any location. In battle though, they are vurnable. Try to keep these as far away from the action as possible. They are mostly unarmed, having only a couple of guns in its secondary battery, so keep them guarded at all cost. They are also one of the most expensive, losing one early on can make you lose the entire campaign.

Building up your base

Constructing airfields and ports is of great importance in this game. So expect many recourses to go into buidling these facilities. To build ports and airfields you will need Engineering, Fuel and supplies. These are available at your main base. You will start with a few of these rescources, but you will get a 100 Engineering and fuel every week (plus some supplies and soldiers). To transport Engineering and Supplies, you will need cargo ships, these are found at the end of your ship catalog. To transport fuel, you will need an oil tanker (also found at the end of the ship catalog). Both types can carry 100 Eng. or Fuel and cargoships can carry 2000 supplies as well. As both upgrades cost a lot, make use of a dedicated supply task forces to keep your bases under development.

The cost of these upgrades are listed below:

Finding the enemy

Intel is key, so make full use of your scouting abilities. The greatest addition to your fleet are your scoutplanes. These tiny unarmed aircraft are way more valuable than fighters or bombers, because they can be launched from your ships. Most light and all heavy cruisers have these aircraft available (as do battleships). To launch these aircraft, go to your fleet and click on “manage cargo”. A list should appear underneath it, select launch aircraft. Select the ship that has scoutplanes and select the number of planes you want to launch. I would suggest launching single aircraft, as the extra scoutplanes won’t provide you with more range or firepower (they are unarmed). This way you can also cover more ground with the scoutplanes of a single cruiser or battleship. Once they are launched, start plotting a course for them to fly. A zig zag in front (to find specific targets) or a cirlce around your fleet (as an early warning system) would be my choice, depending on the situation. Radar can also be used to gain a passive scouting bonus to your fleets spotting abilities. So make shure your scouing task forces have surface radar on at least one of their vessels.

Most action will take place in the “canal” between guadalcanal and the shortland islands and its surroundings, so scouting this area would be advised.

Entering combat

Once an enemy fleet has been spotted, and you think you have the upper hand, you can set a course to intercept the enemy fleet. Try to follow the fleet with your scout planes so you won’t lose sight of it.

If you think you are outgunned, try to move your fleet within range of an island with an airfield, an let fighters and bombers join you in battle. To do this, select an island with an airfield, click on new air, and select the planes that you want to deploy. Bombers are good vs ships, fighters can help you defend your fleet from enemy carrier aircraft.

The battle begins

At the start of a battle your ships will usually be formed up in a line. You can change this if you want before combat by changing the formation. The enemy fleet is usually within sight, altough they can be very far away. Most times you can see them yourself (use the binoculars at the right bottom of the screen), but your ships can’t spot them yet.

Your first task is for your ships to spot the enemy. There are 2 ways to do this. The first one is simply to get your ships closer to the enemy. Having radar will decrease the distance needed to spot the enemy ships, so dont forget to turn them on! The second option only applies if you have aircraft in the area. Use them to fly to the enemy fleet and the ships will appear on the map, and your ships can start targeting the enemy.

Targeting the enemy

Before you can open fire on the enemy, you must first decide where to strike. Ships have to recieve targets from you, so they can start calculating the right trajectory for the first strike. Press T (or click on the target button on the bottom right), and click on the vessel you want your ship to engage. Your ship will start generating a solution. The higer the solution, the higer the chance for a hit. There are many options on how to fire. There are diffrent types of ammo and diffrent types of shooting available. I will go trough them with you.

Ammo types

HE – The main type of ammo on all ships. Most destroyers and light cruisers only have these available. They are usefull against low or non armoured targets such as destroyers and cruisers, but will have limeted effect against battleships.

AP – This type of shell is used against armored ships. Mainly heavy cruisers and battleships. These will be available on cruisers and battleships only, and are used to take out (heavy) cruisers, battleships and carriers.

SS – Short for star shell. It is a type of shell used to light up an enemy fleet during night battles. Firing a few volleys at the enemy with star shells wil increasing the firing solution, and thus accuracy.

Types of firing

The first option to choose from is Loose. With this option guns will fire a loose volly of shells on the enemy. This is very usefull if the enemy is far away and/or your firing solution is low. This way you can score a few hits while closing distance to the enemy.

The second option is full. With this option ships will fire all guns simultaniosly with a closer spread. This is usefull for medium range engagements. Make shure your firing solution is at least 50-60%, otherwise loose firing will be a better option.

The final option is NRRW, wich stands for narrow. With this option guns will firing withoud any spread and try to put as much metal as possible in a small area. This is very usefull for close combat or if your firing solution is very high (85-99%)

There is also the option for spotting. This will make your guns fire slower, as they will keep track of how close your shells get to the enemy, and thus increase your solution every shot. Use this from te beginning till your firing solution is around 50-60%.

Opening fire

If the enemy is spotted, and you have decided which vessel will attack wich vessel, you can start firing your guns. At the beginning use Loose and spot as you close distance. Use AP against cruisers and HE against destroyers and lighter cruisers. If your battle is at night, always start with a couple of vollys of star shells (if available). Try to close distance to the enemy fleet, but always maintain a line of battle (or an other formation). It can be usefull to split up your fleet when the enemy is in range. For example, detach your destroyers and use their speed and mobility to get close to the enemy and make them ready for a torpedo attack, while your cruisers maintain supporting fire from further away.

Wich enemy you will focus on depends on the situation. Not always is the biggest ship the biggest treath. Think about your strenght and your weakness. For example, if you have a lot of destroyers, and want to use them to attack the enemy battleships (your strenght), you should focus on the enemy Light cruisers and destroyers (your weakness) to make way for your destroyers.

Closing in

After the first couple of volleys and miles, your firing solution should increase. Use the infromation above to change your ammo type and firing option to your sitiuation. Try to focus on disrupting the formation of the enemy. A disorganised foe is a great target for your ships. Dont forget to change the course your ships take regulary, so the enemy’s firing solution wont go too high and start getting real close to hitting you.

Close quarters combat

If the fight isnt over when the ships come wihtin close range, start making torpedo runs on the enemy’s large ships. Use the smaller ships to get close enough and start dealing damage. But be wary, as the enemy might do the same, so keep on the lookout for enemy torpedo’s. They can be easily seen by the trail of bubbles they leave behind. Altough amidst the chaos of battle, the can be missed by the player. A couple of torpedos can easily take out a cruiser.

Related Posts:

This guide contains instructions on how to launch and operate aircraft from carriers, some generalised recommendations on how to build and operate a carrier fleet and some basic information of the types of aircraft usable by carriers.

Fleet Building

So, you want to be a Carrier Main?

Well, Carriers are a joy to use and a joy to abuse (others) when used correctly. They can absolutely dominate the battlefield when used with care and as such they are entirely worthy of being called flagships and capital ships.

However, unlike their more traditional Battleship counterpart who loves to get into firing range and tear the opponent to shreds bit by bit (Nice armour you got there, shame my 18′ shell just broke it) the Carrier wants nothing to do with it. In fact, if played correctly the ideal situation is your Carrier never even sees AA fire let alone ship to ship fire.

Because of this standoffish nature, when assembling a fleet for your Carrier you need to drop the notions of a traditional battlegroup. You aren’t trying to overwhelm the opponent with raw firepower, that’s what a Battleship is for, so you don’t build a fleet designed to do that.

No, what you need is a Defensive Operations fleet. This fleet type has three general requirements:

1. RED FLEETS GO FASTA! Carriers are quick, so you don’t want your escorts to slow you down. If it isn’t capable of doing 30 knots or more it probably shouldn’t be there as you want to be able to outpace enemy Battleship and Submarine fleets on the global map to keep your Carrier out of gun reach.

2. I ‘AV ALL DA SKY DAKKA! The biggest threat to Carriers is aircraft (funny that) and as such you will NEED to be prepared for this problem. The more anti-aircraft fire you can shove into your fleet, the better. In particular, keep an eye out for ships with dual purpose guns or multiple overlapping fields of AA fire as these will be more useful. You aren’t going to wipe out the attacking planes, but even a few less can have major impacts.

3. I WANT ALL DA BARREL BOMBS LADZ! Submarines are sneaky little gits and sometimes they are just going to pop up if you aren’t careful or they come from a weird angle. (WHY ARE YOU LOITERING OUTSIDE MY MAIN BASE YOU DAMN GATO!?!?!?) As such, when they do show up you’ll want to be able to quickly and efficiently turn them into an artificial reef.

So make sure that some of your ships are capable of doing this job well.

Combining these three needs into a fleet is usually quite achievable, especially if you make use of ships which cover multiple categories. I will take this moment to point out in particular the IJN Akizuki Class DD, the USN Fletcher Class DD and the USN Atlanta class CL as the three top runners for support vessels within in your Carrier fleets.

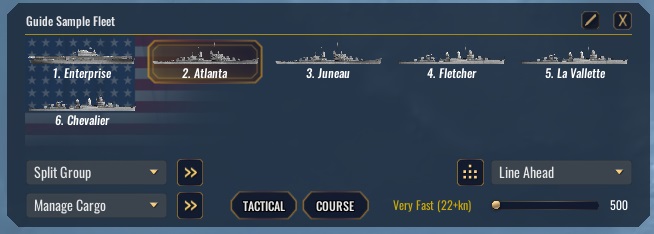

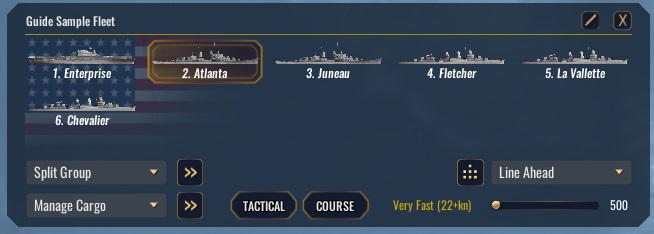

As a final note, keep in mind that your ideal goal is to not actually fight anyone with your carrier group directly. So you can get away with being a bit skimpy if you’re careful. I tend to find that the 1 CV, 1-2 CL’s and 2-3 DD’s are enough to get the job done. Below is an example of a well fleshed out Carrier group for the USN.

Carrier Fleet Positioning

So now that we have an idea of what our Carrier fleet should look like for its composition, lets discuss where our fleet should be. This section will be smaller than the last one I promise.

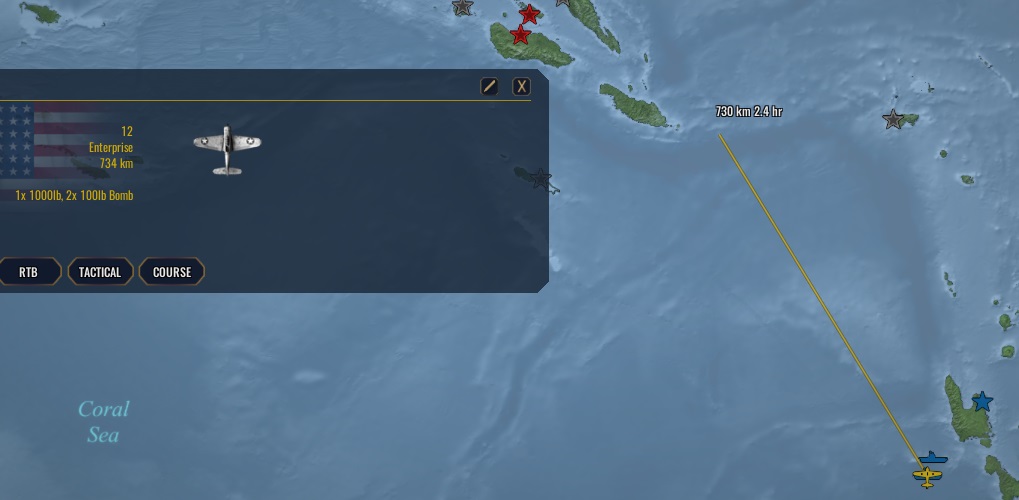

First things first, Carrier fleets don’t want a fair fight. You want to be able to strike your enemy and run, and that is something which you can do very effectively with your long reach. Carrier based aircraft tend to have a range of at least 500-650km and can traverse this in a matter of in-game hours.

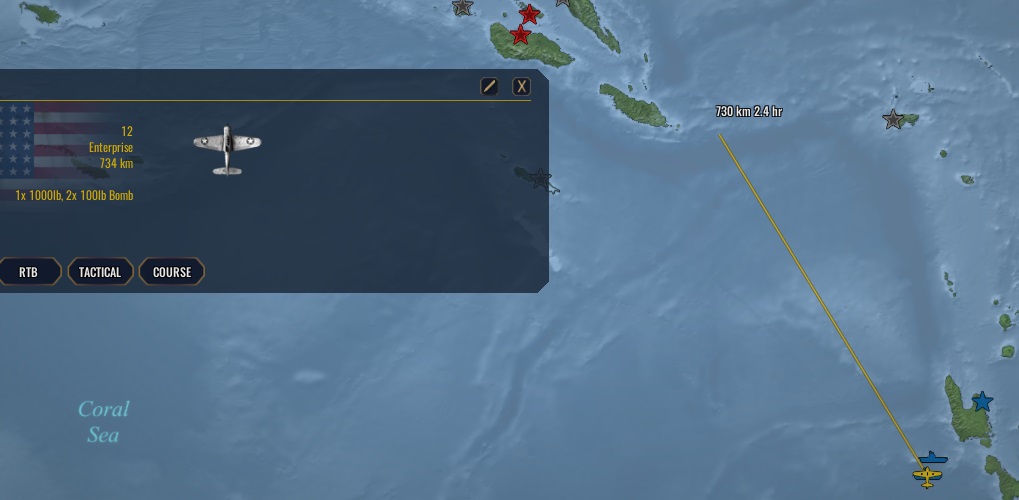

For reference, this is the strike range of the SBD Dauntless from the USN to give an idea of actually how long the attack range is.

The exact distance for each aircraft can be seen in their Endurance stat, such as in the example below.

With this in mind, you can happily maintain a safe distance of 300-400km from any potential threat and through the use of spotting (we will discuss this later) you should be able to avoid any confrontations whilst continuing to strike your foe with impunity.

One thing to note is that you cannot launch planes between 1700-0500hrs. This means that once you get past the 1700hr mark it is not a bad idea to pull your carrier fleet an extra 100-200km as you will not be able to defend yourself as well.

Getting your Aircraft Airborne

The interface for WotS is admittedly not the most intuitive and therefore I can understand why some players don’t realise how to get their aircraft in the air. So lets get onto the explanation and the reason why this guide was made.

Step 1: Own a carrier. Duh.

Step 2: Select your Carrier fleet.

Step 3: Select the bottom left drop down menu and choose the “Launch Aircraft” option.

Step 4: Select your Carrier and then hit the button next to the “Launch Aircraft” menu.

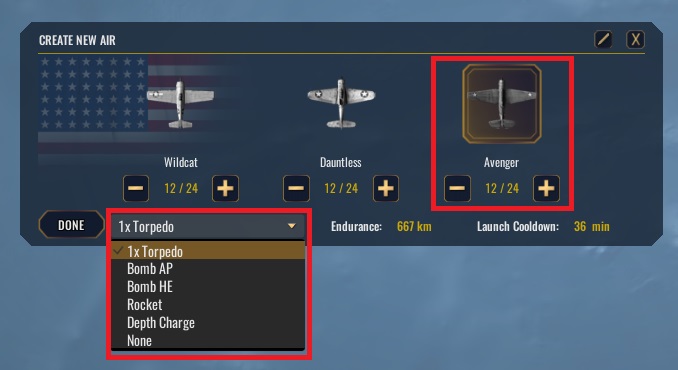

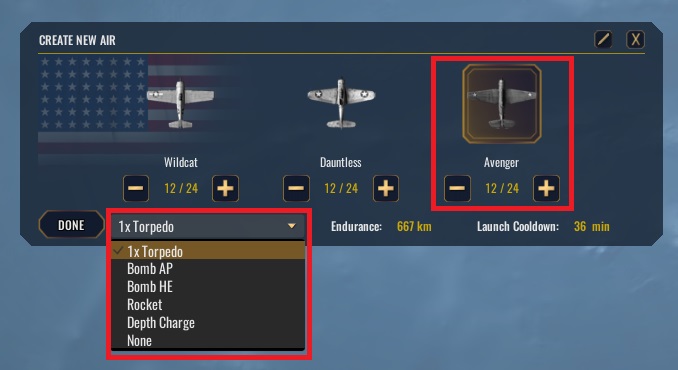

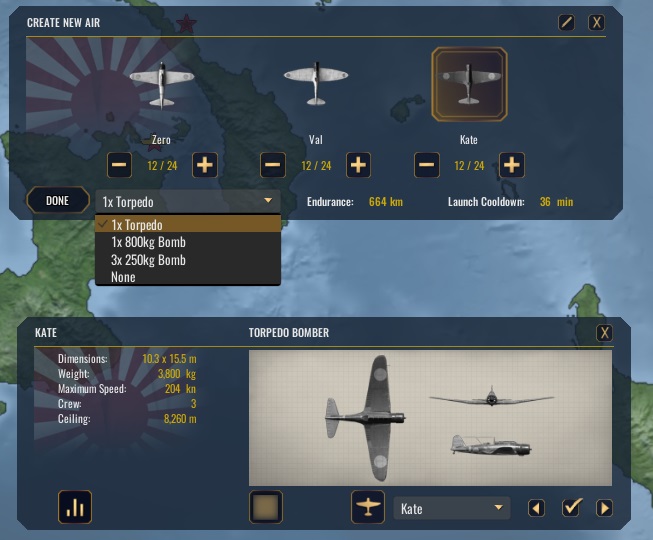

Step 5: This takes you to the “Create New Air” menu. Select the type of aircraft you wish to send out, and specify the number you wish to send in the group. (Between 1-12) In the drop down menu you can also choose the ordnance the aircraft is using. Once you’ve setup the group you want, hit “Done.”

Step 6: Now you can control your squadron by selecting it. “RTB” = Return to Base, which orders the planes to return to their point of origin. “Course” lets you change course as normal. “Tactical” also does the same as normal and takes you into battle mode with local units, which will be your primary way of using strike craft.

Step 7: Sometimes aircraft will get a combat initiation trigger against enemy fleets but this is not always the case. With this in mind, make good use of the “Tactical” button to get your strikers on target as needed.

Operating Aircraft

First let’s take a quick look at the different aircraft that Carriers can operate:

1. The Japanese Zero / American Wildcat are the Carrier Fighters found in WotS. They are fast, agile and armed with machine guns capable of gunning down other aircraft or strafing surface targets at low altitude.

2. The Japanese Val / American Dauntless are the Carrier Dive Bombers found in WotS. While not as fast as their fighter counterparts, they still can maintain a quick pace. Each has a rear gunner which can tickle enemy fighters and a payload of bombs for hitting surface targets.

3. The Japanese Kate / American Avenger are the Carrier Multi-Role Bombers found in WotS. Slower than the others, they are the most offensively oriented when ti comes to anti-shipping gear and can equip a variety of payloads.

And now for a more in-depth look:

The A6M2 “Zero”:

As a fighter, you’ll find yourself using the Zero in one of three ways. Scouting is the most common, as information wins wars. Sending groups of 2-4 Zeroes out regularly to scout is necessary to track targets and maintain safety around your Carrier. Intercepting incoming bombers is an extension of this role and should be prioritised when possible. Finally, a wing of 12 fighters can be scrambled should an enemy bomber wing make it to your carrier, so always try to keep at least 6-12 fighters on deck in case of emergency. To do this, select the fleet before hitting “Begin” and follow the instructions from Section 3 of this guide.

The Aichi D3A “Val”:

Unsurprisingly, these Dive bombers are meant for one job and good at that one job. Have them climb to 1,000m at the start of an engagement, pick your target and give it the good news with some good old fashioned bombs straight through the deck. This is effective vs any class of Surface Vessel, even Submarines should they hit. Keep in mind however the relative short range of the aircraft type, meaning you should hold these craft in reserve until you have found a target for them.

When hitting a target from directly ahead/behind, set your squadron to the Line Ahead formation. When going at a target from the side, I recommend the Vic formation.

The B5N2 “Kate”:

Slower but not necessarily sturdier, the Kate rewards high risk high reward. Her torpedoes require you to get low and slow in order to deploy but will devastate warships if multiple of these aircraft succeed in landing their hits. Alternatively, you may attach bombs to the aircraft and instead attempt to land heavier hits than the Val can muster from the relative safety of higher altitudes.

When torpedo bombing, I recommend getting your Kate’s into groups of 3 in the line abreast formation. This will have the best effect. When doing high altitude bombing, Vic formation should be sufficient.

The F4F Wildcat:

The Wildcat mimics the Zero with it’s role within the Carrier fleet. First, it’s obviously your fighters and meant for taking down enemy aircraft. Second, it’s a quick reaction force for if the carrier is attacked by enemy aircraft. And thirdly, it can act as a scout, although it’s range is inferior to the Zero by 310km. However it trades this inferior range for much better armour, meaning it can survive IJN AA considerably better.

The SBD Dauntless:

The premier scout for the USN and their Dive bomber, the Dauntless will take you places. Send these out in flights of 4 for scouting missions or wings of 12 to devastate enemy shipping, especially Cruiser class vessels. Of special note, the Dauntless is considerably tougher than the Val and in combination with the weak IJN AA can survive a lot more time over an enemy fleet than their Japanese counterparts.

When hitting a target from directly ahead/behind, set your squadron to the Line Ahead formation. When going at a target from the side, I recommend the Vic formation.

The TBF Avenger:

The toolbox bomber of this game, the Avenger has a large variety of payload options that allow it to be effective at, well, any type of anti-surface warfare. Her torpedoes can be very dangerous against enemy shipping, however they are usually duds so if you have dud torpedoes on be ready to cry. Her AP bombs will give Battleships headaches, her HE bombs will make Destroyers wish you’d sent Dauntlesses instead, her Rockets will let you know where the enemy isn’t by all the splashes they’ll leave behind and the Depth Charges will make Submarines hate your soul.

Trial and error will be needed with this, but as some basic pointers, the torpedoes are great if you have duds turned off and pointless if you don’t. The bombs work as well as bombs should but you will probably get more consistency from the Duantlesses. Rockets are having a weird time atm with accuracy but are nasty if they hit. Depth Charges are amazing as long as you have the Submarine spotted. They will even deal some damage (limited) to Submarines on the surface so go ham with them.

Misc Other Information

1. Aircraft will remain airborne for their full distance allowance even after 1700, so launching as many aircraft as you can just before 1700 is a wise idea. An extra 2 hours of air cover makes the night seem just that little bit brighter for your future.

2. Carriers need an in-game hour after launching a squadron before they can launch another squadron, so if you want to launch large strikes you may need to stagger your attacks or have one squadron wait for the other. If the latter, keep in mind that the effective distance of your squadron will be reduced.

3. Only 24 friendly aircraft can be in a battle at a time, so if you want to use all 24 strike craft make sure to pull back friendly fighters and spotter craft ahead of time to let your bombers bring the rain.

4. If your Carrier fleet is being attacked by a surface fleet or Submarine directly, you can select the Carrier fleet and launch a squadron (up to 12 planes) at the last second before hitting begin. This squadron will spawn at low altitude almost directly above the Carrier in the battle.

5. Aircraft returning to base can still take part in a fight if you time it right by using the “Tactical” button.

Here we come to an end for War on the Sea A Basic Guide to Operating Carriers. hope you enjoy it. If you think we forget something to include or we should make an update to the post let us know via comment, and we will fix it asap! Thanks and have a great day!

A brief overview on how to use submarines in War on the Sea to sink ships, as well as how to find and destroy enemy submarines.

Contents

- Submarine and Anti-Submarine Warfare Guide

- Introduction

- Submarine Classes and Armaments

- Surface Ship Classes and Armaments

- Sonar

- Submarine Strategy

- Submarine Attacks

- Escort Evasion

- Anti-Submarine Strategy

- Anti-Submarine Tactics

Introduction

Submarine attacks in War on the Sea can be incredibly powerful, sinking huge amounts of tonnage while risking very little. However, the most effective way to use your submarines isn’t always intuitive, nor is it necessarily obvious how you should go about hunting down your enemy’s submarines. If you’re unfamiliar with WWII era submarine and anti-submarine tactics I hope that this guide can help you get started.

I’ll firstly be covering some basic concepts and historical context, so if you’re already familiar with this information please feel free to scroll down to the actual gameplay tips located below.

Submarine Classes and Armaments

WWII era submarines spent most of their time on the surface, using diesel engines to travel the long distances to their patrol areas and only submerging to attack or evade. While submerged, they used electric batteries for propulsion, and were much, much slower. On the surface, subs were faster than merchants but slower than other warships. Submerged, the subs were slower than everything else by a wide margin.

The main armament of all submarines was the torpedo, spreads of which could be launched while submerged at periscope depth to hopefully catch the enemy unaware. They were also typically armed with a light anti-aircraft gun and a deck gun, which could be used (very rarely) to attack surface targets and in some navies could also fire flak.

The US subs available in the game’s Guadalcanal campaign consist of the Tambor and Gato classes. These were “fleet submarines,” larger than the subs of other navies and designed to keep up with and scout for the surface fleet across the vast distances of the Pacific. The Tambor is distinct from the Gato in that it is very slightly slower, and cannot dive as deep. The succeeding Balao and Tench classes, which can dive even deeper, are modeled in game but are unavailable for the campaign.

In 1942 US subs are armed with the (historically very unreliable) Mark 14 torpedo, which in game will travel ~9000 yards at 30.5 kn. The subs have both passive and active sonar and, very usefully, surface and air radar. Many Japanese ships have excellent passive sonar, so you will want to avoid using the active sonar most of the time or you will give away your presence. By contrast, most Japanese ships have no radar to speak of, so you will be able to use your own with near impunity.

The Japanese subs available in game are the Type B1 and Type B2, which for the purposes of the game are identical. These were even larger than their American counterparts and even featured a catapult launched scout plane that was stored in a compartment on the deck, a feature fully modeled in game.

In 1942 Japanese subs were armed with the excellent Type 95 torpedo, a variant of the famous Type 93 “Long Lance” torpedo used by Japanese destroyers. In game it will travel ~8000 yards at a very fast 46 kn, which gives you somewhat more versatility regarding which targets you can attack and when. Historically, the Type 95 also had a larger warhead than the Mark 14, which I suspect may be modeled in game but don’t know for sure. The Type B1 and B2 subs have comparable active sonar and better passive sonar than American subs, but no air radar.

As mentioned previously, in 1942 the Mark 14 torpedo was notoriously unreliable: it would run too deep, detonate too early or not at all, and in some horrifying cases the gyro would fail and the torpedo would circle around towards the sub that fired it. This is modeled in game as a much higher rate of duds for the Mark 14: in the region of 33% duds vs. around 5% duds for the Type 95. If you’re playing with duds enabled (which you should be, to experience that authentic submarine skipper pain) as the US this will need to be taken into account.

Surface Ship Classes and Armaments

The main type of ship used for anti-submarine warfare in game is the destroyer. Destroyers are extremely fast, maneuverable, equipped with passive and active sonar, and capable of launching patterns of depth charges off their sterns to damage submerged subs. There are many different classes of destroyers in both the Japanese and US navies, but for the purpose of in game ASW all of the destroyers within a given navy are about as capable as the next. One thing to note is that Japanese ships have better passive sonar than US ships, so if you’re playing as the US you will need to be more careful with your subs’ noise levels.

There are a handful of exceptions worth mentioning:

On the US side, Atlanta class light cruisers are also equipped with sonar and depth charges, though their lower speed and larger size relative to destroyers makes them somewhat awkward in an ASW role.

On the Japanese side, The Momi class destroyers, among the oldest and smallest destroyers in the Japanese navy, have neither sonar nor depth charges. The Oyodo class light cruisers are equipped with passive and active sonar, but are only capable of dropping depth charges one at a time off the stern in a much less effective pattern. Amusingly, several classes of Japanese heavy cruiser are also equipped with passive sonar and depth charges, again dropped one at a time. Actually hitting anything with these huge ships and weak patterns is a tall order, but it can be pretty funny. Lastly, Japanese battleships and carriers are equipped with passive sonar, and while they have no depth charges, they will attempt to evade your subs if they detect you.

Sonar

Detecting enemy submarines and avoiding detection for your own subs revolves entirely around sonar, and understanding it is vital to success and survival. There are two types of sonar: passive and active.

Passive sonar essentially just involves sticking microphones into the water and listening for the sounds made by enemy ships: the engines, the sound of turbulence around the hull, and any noise the crew might be making inside. This is limited by contact noise level, the distance from the contact, the local sea conditions, and any masking noise the listening ship may be making.

Active sonar involves making some kind of noise and listening for the echo bouncing off the hulls of enemy ships (this is the high pitched “ping” noise you hear on TV literally every time a submarine is on screen). Active sonar has the advantage of being able to detect contacts that are being perfectly silent, and it allows the listening ship to build a target solution very quickly. It has the disadvantage that it involves continuously making a lot of very loud noise, which will immediately alert any nearby vessels with passive sonar to your presence. What’s worse, active sonar needs to travel all the way to the target and back in order to detect a contact, whereas it only needs to travel as far as the enemy ship in order to be heard via passive sonar. This means that enemy ships can hear your active sonar at a much longer range than you can use it to detect the enemy.

For surface ships this hardly matters: surface ships are so noisy and obvious than any nearby subs almost certainly already know they’re there, and WWII era subs can’t realistically do anything to harm a maneuvering destroyer anyway. There is no harm to turning on the active sonar on your destroyers when hunting for enemy subs. By contrast, a submarine’s best defense is to remain hidden, and turning on the active sonar is a sure way to let everyone know you’re there. This is not recommend unless dodging depth charges is your hobby. Active sonar is limited by distance to contact, the size of the contact (bigger ships reflect more sound), the facing of the contact (a side-on contact will reflect sound waves more strongly), local sea conditions, and again the amount of noise the listening ship is making. Having the seabed close behind a submarine will also make it harder to detect with active sonar, since it’s harder to distinguish the return from the contact vs. the return from the sea floor.

Ships that are traveling faster will make more noise due to louder engines and greater turbulence around the ship’s hull. This will make the ship easier to detect via both passive and active sonar (turbulence helps to reflect active sonar sound waves). Higher speeds will also make the ship’s passive and active sonar less effective, as it will be harder to hear the noise of enemy contacts over the noise the listening ship is making. Both surface ships and submarines also have an area directly behind them called the “baffles,” where they can’t detect anything by either active or passive sonar.

All sonar is affected by the local sea state, which in game is indicated as 0 through 8, with 0 being the calmest seas and 8 being the roughest seas. Rough seas create a lot of ambient noise, which makes listening for enemy contacts much harder. In sea states 0 through 3, submarines can usually be located with relative ease. In sea states 4 and 5 surface ships will need to be going slow and close to pick up a contact. At sea states 6 and above ships will have to be perfectly stationary and directly above an enemy sub in order to hear it, if it’s even possible at all.

If the seas are relatively calm there may also be a thermal layer, which is a depth at which the temperature of the ocean drops sharply. Thermal layers tend to reflect sound waves away from the layer, which makes it harder for ships on opposite sides of the layer to hear each other. Sound waves created above the layer will also tend to bounce between the surface and the layer, which creates a “duct” in which sound waves will travel much farther than they would otherwise. The layer depth, strength, and strength of the duct are available in the menu. A strong layer can help your submarines avoid detection and make getaways in quiet seas where escape would otherwise be impossible.

I also suspect that cavitation may play a roll in sub detection, depending on the fidelity of the WotS sonar model. This is pure conjecture on my part, since it’s not mentioned anywhere in the manual, but cavitation itself seems to be modeled in the game so it seems worth mentioning. Cavitation is when the propeller of the ship is spinning hard enough to turn some of the water around it to gas, and it is extremely loud. You can tell whether or not your subs are cavitating by the presence or absence of bubbles around the propeller. The deeper your sub is, the faster it can go without cavitating. Again, no idea whether noise from cavitation is actually used for passive sonar detection in game, but it can’t hurt to avoid it when possible.

Submarine Strategy

in the campaign, your subs are best used as scouts, convoy raiders, and to pick off any large warships that happen to wander past. Subs cost very few command points and can be deployed in large numbers, so you’ll want to deploy a number of them between the enemy home port and any important objectives in order to intercept convoys. It’s also useful to have a bunch of them positioned around your important fleets, especially your carriers, to detect and harass any enemy surface groups that might otherwise catch you by surprise.

When attacking an enemy surface group, you’ll need to prioritize your targets carefully. You are realistically only going to get one spread of torpedoes away before you have to disengage. This is for two reasons: firstly, as soon as your torpedoes hit anything, the other ships will begin evading, making it very difficult to hit them with any follow up attacks. Secondly, on torpedo impact any escorts will immediately begin making a beeline for the location where you launched the torpedoes from, and it is very much in your best interest not to be there when they arrive.

Targeting destroyers and light cruisers is generally not advisable, given that they are difficult to hit and not worth many command points. If there is only one destroyer guarding a convoy, however, it might be worth trying to knock it out first so that you can reengage the convoy later and attack with no risk of reprisal. If you do manage to successfully get a spread off on a destroyer or light cruiser, it will only take one or two hits to sink it.

Heavy cruisers, battleships, or (the Holy Grail) carriers are much better targets. They’re larger, slower, worth a bunch of command points, and even if you don’t sink them that’s still a lot of firepower out of the fight for the near future. It’s worth giving these a full spread of torpedoes, since depending on the difficulty you’re playing at the largest ships can sometimes eat even a full spread and still stay afloat, especially if you’re using Mark 14’s.

When attacking convoys, it’s best to go for oilers first. Oilers are larger, worth more command points, and no matter how much engineering equipment and supplies the enemy has they won’t be able to upgrade their ports and airfields without any oil. A full oiler is also extremely flammable, understandably, so if you manage to start any kind of fire at all it’s likely to grow into a raging inferno that will take the whole thing down.

I have experimented somewhat with using groups of subs in “wolf pack” attacks. It allows you to really ruin the day of any one particular surface group at the expense of having much less coverage over the wider area. It also requires very careful coordination of your torpedo attacks: if one torpedo spread arrives much earlier than the others, then your other targets will begin maneuvering and those other spreads will likely miss. Personally I prefer the enhanced scouting and reduced micromanagement of using lone subs, but your preferences may vary.

Submarine Attacks

When you first begin an encounter with an enemy surface group, your sub(s) will spawn submerged and likely ahead of the enemy group, in a good position to make a torpedo attack. The very first thing you need to decide is whether you’re going to make an attack at all. Your biggest two concerns are the composition of the surface group and the local sonar conditions. If the surface group is just a few destroyers, it’s probably worth saving your torpedoes for a convoy or large warship.

The best sonar conditions in which to make an attack are during high seas or in the presence of a strong thermal layer, which will make it much easier to make your escape after your attack. Attacking during quiet seas with no thermal layer will nearly guarantee that the enemy escorts will be able to find you, which tends to have a strongly negative effect on your submariners’ life expectancy. Also, if the enemy escorts are going to be within about 2000 or 3000 yards of your sub when you make your attack, it will make it much more difficult to get away. Finally, you should bear in mind that you can only reasonably attack a ship with a constant heading and speed. If your target is maneuvering or changing speed, it’s not worth wasting your torpedoes. If you decide it’s not worth attacking, just set your speed to 0, go to ultra quiet, and start the retreat timer.

Once you’ve decided to make your attack and chosen a target, you need to maneuver into position. Torpedo attacks are most accurate when the torpedoes impact the target side-on with a low gyro angle. This means that you want your sub’s heading to be off by 90 degrees relative to the heading of your target. You also want the torpedoes to run as straight as possible without having to turn very much once they’ve armed. US subs have rear torpedo tubes and can attack while facing away, which makes it easier to begin your escape at the cost of only being able to fire a spread of 4 torpedoes instead of 6. Japanese subs only have forward torpedo tubes and need to be facing their target.

Once you’re in position, kill your speed and wait for your target solution to build up. Your target solution will increase by correctly identifying your target and observing it using your scope, passive sonar, and radar (only if playing as the US: using your radar as the Japanese is not advisable as all US warships will be able to pick up your signal). Active sonar can also help, but you should only turn it on if there are no ships with any passive sonar in the entire surface group, which is very rare. Also, a few Japanese warships do in fact have radar, and you will want to make sure you’re not facing one of them before turning on your radar or your radar signal will give you away.

While waiting for your target solution to build, select how many torpedoes to fire with what spread angle. When playing as the US, the Mark 14 is so unreliable that you’re probably just going to want to go ahead and fire a full spread of six. You’ll thank me when 5 out of those 6 turn out to be duds (yes, this has happened to me. No, I’m still not over it). With Japanese subs you can afford to be more frugal, and throw on maybe one more torpedo than you think you need on the off chance you get a dud.

If you want all your torpedoes to hit the same ship, an angle of 1 degree is best. If you just want to cause as much havoc as possible in a large, crowded convoy, you can crank it all the way up to 10 degrees. If your max firing solution is lower than 99%, usually due to low visibility, you’ll want to increase your angle and add more torpedoes to taste.

Once your solution is as good as it’s going to get, fire your torpedoes once the gyro angle is close to zero (you can see the gyro angle of the current solution by mousing over the torpedo room). Immediately set your depth the the lowest you can go (you can get away with going a bit lower than your test depth) and set a course away from the enemy escorts as fast as you can go. If you’re in a strong duct, you may want to hold off increasing your speed until you’re below the layer to avoid alerting the enemy prematurely. All going to plan, your enemy should be unaware right up until the torpedoes hit them, and you should be long gone by the time the escorts reach your firing position.

The steps to a successful getaway:

- Get as far away as possible as fast as possible.

- Get as deep as possible.

- Face directly away from searching escorts, to minimize active sonar return.

- Hug the seabed if possible, again to avoid active sonar.

- Rig for ultra quiet to stop reloading noise.

- If escorts are nearing your sub despite your efforts, slow to 1 or 2 kn to hopefully avoid passive detection.

- Avoid letting your sub cavitate (again, not sure if this is modeled).

Keep a close eye on the enemy escorts. If they’re still heading towards where you were, you’re still in the clear. If they start heading towards where you are, you have a problem.

Escort Evasion

If the enemy escorts pick you up on their sonar, you’re in serious trouble. Dodging depth charges launched by a ship going 35 kn in a ship going 8-9 kn is a tall order. You want to be as deep as your sub can go, which will give you more time to dodge while the depth charges fall from the surface. Not getting blown out of the water will require a bit of luck, but here’s a method I’ve found that seems to work.

- Go to max speed and line up your heading with the heading of the incoming escort.

- As soon as the depth charges start dropping, turn the rudder fully to port or starboard.

- Pray.

If you survive that pattern of depth charges, the good news is that you’re now in the escort’s baffles, which means they’ve lost contact with you. Reduce your speed to 1-2 kn, turn away from the escort, and if the seas are noisy or there’s a strong layer you might be able to slink away without being reacquired. More likely, the escort will turn around, find you again, and come in for another run, and you’ll need keep dodging depth charges until your pursuers run out.

Japanese destroyers and the Oyodo class normally have 36 depth charges (though some of the early destroyer classes have more or less), enough for two patterns of 15 and one itty bitty pattern of 6. The Japanese heavy cruisers usually have 12 charges, and can only drop 5 at a time, but for some bizarre reason the Takao class has a whopping 60. Dodging twelve runs of 5 charges is easy, but tedious. US destroyers and the Atlanta class, meanwhile, all have 60 depth charges each, enough for four big runs, so buckle up.

Once the escorts run out of depth charges, they’ll keep doing dry runs on your sub. I suppose technically the escorts could just keep following you until either you run out of battery/oxygen and need to surface or sonar conditions change and you can get away, but that would take hours and isn’t modeled in game, so just start the retreat timer.

If you do take any damage from the depth charges, you’re likely screwed. Your repair crew might be able to contain the flooding and let you keep going, but more likely those sections are destroyed and you’re now sinking towards your crush depth. If the seabed is above your crush depth you can try to rest silently on the sea floor, which might give you just that little bit of an edge to confound enemy active sonar. If you should be so lucky, the enemy escorts will just keep circling your last known position ad infinitum, so go ahead and start the retreat timer.

If you’re in deep waters, however, your last desperate measure is to do an emergency blow ballast and surface the ship. At this point you’re essentially as good as sunk. Compared to the hulls of surface ships the pressure hull of a submarine might as well be made out of paper, and even an armed merchant will make short work of you if it catches you on the surface. The best you can hope for is to take a couple of spiteful shots with your deck gun and maybe knock out a turret or two before you go down fighting.