Текущая версия страницы пока не проверялась опытными участниками и может значительно отличаться от версии, проверенной 13 октября 2019;

проверки требуют 44 правки.

Перечень фактических (де-факто) руководителей СССР и Коммунистической Партии Советского Союза.

В годы правления Владимира Ленина формально высшей государственной должностью был Председатель ВЦИК, но вся реальная власть была сосредоточена в Совете народных комиссаров, который и возглавлял Ленин. Должность Генерального секретаря Центрального комитета РКП (б)—ВКП (б)—КПСС была учреждена в апреле 1922 и стала фактически важнейшей государственной должностью после смерти Ленина. Влияние Иосифа Сталина, занимавшего этот пост, росло, и к концу 1920-х годов он фактически обладал неограниченной властью.

Формально же к 1953 Сталин являлся лишь главой исполнительной власти страны (Председатель Совета Министров СССР). Именно поэтому сменивший его на этом посту Георгий Маленков, являвшийся негласным преемником Сталина, стал новым лидером и главой государства[источник не указан 1467 дней]. Маленков вплоть до 1955 возглавлял Совет Министров, однако начиная с избрания на вновь созданную должность Первого секретаря ЦК КПСС в сентябре 1953 постепенно набирает политический вес Никита Хрущёв, который, как считается, сыграл ведущую роль в устранении одного из основных конкурентов в борьбе за власть после смерти Сталина, Лаврентия Берии. В 1955 году Хрущев смещает Маленкова с поста Председателя Совета Министров СССР и власть окончательно переходит в его руки. С 1958 года и вплоть до отставки он совмещает должность Председателя Совмина и главы партии.

В последующем в СССР пост Председателя Совета Министров не воспринимался как главный государственный пост. Юридически (по конституции СССР) руководителями государства были лица, назначаемые на должность Председателя Президиума Верховного Совета СССР (позже — Председателя Верховного Совета СССР). С 1988 этот пост занял Михаил Горбачёв, что позволяло ему, являясь фактическим главой государства, быть руководителем и партии, и государственной власти. Исполнительную власть тогда возглавлял, занимая пост Председателя Совета Министров, Николай Рыжков. С марта 1990 Горбачёв совмещал посты Генерального секретаря ЦК КПСС и Президента СССР. Пост Президента сменил пост Председателя Верховного Совета в качестве главы государства, оставив второму лишь функции руководителя законодательной власти страны, но не руководителя самого государства. Тогда же была отменена статья 6 Конституции СССР и в результате КПСС лишилась монополии на власть, но при этом оставалась правящей партией до событий 19-21 августа 1991 года в Москве. 25 декабря 1991 года СССР окончательно перестал существовать. За 69 лет существования СССР фактически было всего 8 руководителей партии и государства (включая Маленкова, который возглавлял только правительство)

Список руководителей[править | править код]

| Руководитель | Название должности | Период | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Владимир Ильич Ленин | Председатель Совета Народных Комиссаров РСФСР и СССР. | 8 ноября 1917 — 21 января 1924 |

|

|

Иосиф Виссарионович Сталин | Генеральный секретарь Центрального Комитета Российской Коммунистической партии (большевиков) (с 1925 г. — Всесоюзной Коммунистической партии (большевиков), с 1952 г. — Коммунистической партии Советского Союза) (с 3 апреля 1922 г. до 5 марта 1953 г.), Председатель Совета Министров СССР (с 6 мая 1946 г. по 5 марта 1953 г.) | 21 января 1924— 5 марта 1953[1] |

|

|

Георгий Максимилианович Маленков | Председатель Совета Министров СССР | 5 марта— 7 сентября 1953 |

|

|

Никита Сергеевич Хрущёв | Первый Секретарь Центрального Комитета Коммунистической партии Советского Союза | 7 сентября 1953 — 14 октября 1964 |

| Председатель Совета Министров СССР | 27 марта 1958 — 15 октября 1964 | ||

|

|

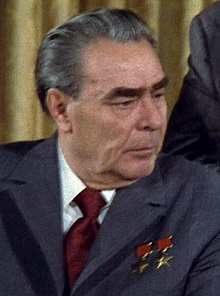

Леонид Ильич Брежнев | Первый секретарь Центрального комитета Коммунистической партии Советского Союза | 14 октября 1964 — 8 апреля 1966 |

| Генеральный секретарь Центрального комитета Коммунистической партии Советского Союза | 8 апреля 1966 — 10 ноября 1982 | ||

|

|

Юрий Владимирович Андропов | Генеральный секретарь Центрального комитета Коммунистической партии Советского Союза | 12 ноября 1982 — 9 февраля 1984 |

|

|

Константин Устинович Черненко | Генеральный секретарь Центрального комитета Коммунистической партии Советского Союза | 13 февраля 1984 — 10 марта 1985 |

|

|

Михаил Сергеевич Горбачёв | Генеральный секретарь Центрального комитета Коммунистической Партии Советского Союза | 11 марта 1985 — 24 августа 1991 |

| Президент СССР | 15 марта 1990 — 25 декабря 1991 |

Список «Троек»[править | править код]

После смерти Ленина в 1924 году и Сталина в 1953 году, в высшем руководстве СССР образовывалась форма олигархии — «тройка». Фактически во главе страны вставал триумвират из самых влиятельных политических деятелей. Такие союзы не были долговременными и возникали на время партийной борьбы.

| Члены

(годы жизни, должность) |

Примечание | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Май 1922 — Апрель 1925 |

Лев Каменев (1883—1936) |

Иосиф Сталин (1878-1953) |

Григорий Зиновьев (1883-1936) |

Тройка сформировалась во время болезни Владимира Ленина с целью отстранения Льва Троцкого от власти. После смерти Ленина и смещения Троцкого, между членами триумвирата начались разногласия. Тройка распалась в апреле 1925 года, и Зиновьев с Каменевым оказались в оппозиции к Сталину. |

| Председатель Моссовета | Генеральный секретарь ЦК РКП(б) | Председатель Ленсовета | ||

| Март — Июнь 1953 |

Лаврентий Берия (1899—1953) |

Георгий Маленков (1901-1988) |

Никита Хрущёв (1894—1971) |

Тройка образовалась после смерти Сталина. Изначально Маленков опирался на поддержку Берии, который возглавлял МВД, но позже перестал делать ставку на союз с ним. В июне Маленков поддержал Хрущёва, организовавшего арест Берии. |

| Министр внутренних дел СССР | Председатель Совета Министров СССР | Секретарь ЦК КПСС |

См. также[править | править код]

- Правители Российского государства

- Президенты России

- История СССР

- Лев Троцкий

- История России

Примечания[править | править код]

- ↑ Сталин — статья из Большой советской энциклопедии (3-е издание)

Литература[править | править код]

- Andrew, Christopher; Gordievsky, Oleg. KGB: The Inside Story of Its Foreign Operations from Lenin to Gorbachev (англ.). — HarperCollins Publishers, 1990. — ISBN 978-0060166052.

- Brown, Archie (англ.)русск.. The Gorbachev Factor (англ.). — Oxford University Press, 1996. — ISBN 978-0-19-827344-8.

- Brown, Archie (англ.)русск.. The Rise & Fall of Communism (неопр.). — Bodley Head (англ.)русск., 2009. — ISBN 978-0061138799.

- Armstrong, John Alexander. Ideology, Politics, and Government in the Soviet Union: An Introduction (англ.). — University Press of America (англ.)русск., 1986.

- Bacon, Edwin; Sandle, Mark. Brezhnev Reconsidered (неопр.). — Palgrave Macmillan, 2002. — ISBN 978-0333794630.

- Baylis, Thomas A. Governing by Committee: Collegial Leadership in Advanced Societies (англ.). — State University of New York Press, 1989. — ISBN 978-0-88706-944-4.

- Cook, Bernard. Europe since 1945: An Encyclopedia (неопр.). — Taylor & Francis, 2001. — Т. 1. — ISBN 978-0815313366.

- Clark, William. Lenin: The Man Behind the Mask (неопр.). — Faber and Faber, 1988. — ISBN 978-0571154609.

- Duiker, William; Spielvogel, Jackson. The Essential World History (неопр.). — Cengage Learning (англ.)русск., 2006. — С. 572. — ISBN 978-0495902270.

- Europa Publications Limited. Eastern Europe, Russia and Central Asia (неопр.). — Routledge, 2004. — ISBN 978-1857431872.

- Ginsburgs, George; Ajani, Gianmaria; van den Berg, Gerard Peter. Soviet Administrative Law: Theory and Policy (англ.). — Brill Publishers (англ.)русск., 1989. — ISBN 978-0792302889.

- Gorbachev, Mikhail (англ.)русск.. Memoirs (неопр.). — University of Michigan: Doubleday, 1996. — ISBN 978-0385480192.

- Green, William C.; Reeves, W. Robert. The Soviet Military Encyclopedia: P–Z (неопр.). — University of Michigan: Westview Press (англ.)русск., 1993. — ISBN 978-0813314310.

- Gregory, Paul. The Political Economy of Stalinism: Evidence from the Soviet Secret Archives (англ.). — Cambridge University Press, 2004. — ISBN 978-0521533676.

- Hill, Kenneth. Cold War chronology: Soviet–American relations, 1945–1991 (англ.). — University of Michigan: Congressional Quarterly (англ.)русск., 1993. — ISBN 978-0871879219.

- Lenin, Vladimir (англ.)русск.. Collected Works (неопр.). — 1920. — Т. 31. — С. 516.

- Marlowe, Lynn Elizabeth. GED Social Studies (неопр.). — Research and Education Association, 2005. — ISBN 978-0738601274.

- Paxton, John. Leaders of Russia and the Soviet Union: from the Romanov dynasty to Vladimir Putin (англ.). — CRC Press, 2004. — ISBN 978-1579581329.

- Phillips, Steven. Lenin and the Russian Revolution (неопр.). — Heinemann (англ.)русск.. — ISBN 978-0-435-32719-4.

- Rappaport, Helen (англ.)русск.. Joseph Stalin: A Biographical Companion (неопр.). — ABC-CLIO, 1999. — ISBN 978-1576070840.

- Sakwa, Richard (англ.)русск.. The Rise and Fall of the Soviet Union, 1917–1991 (англ.). — Routledge, 1999. — ISBN 978-0-415-12290-0.

- Reim, Melanie. The Stalinist Empire (неопр.). — Twenty-first Century Books (англ.)русск., 2002. — ISBN 978-0-7613-2558-1.

- Service, Robert. History of Modern Russia: From Tsarism to the Twenty-first Century (англ.). — Penguin Books Ltd, 2009. — ISBN 978-0674034938.

- Service, Robert (англ.)русск.. Stalin: A Biography (неопр.). — Harvard University Press, 2005. — ISBN 978-0674016972.

- Taubman, William. Khrushchev: The Man and His Era (неопр.). — W.W. Norton & Company (англ.)русск., 2003. — ISBN 978-0393051445.

- Tinggaard Svendsen, Gert; Svendsen, Gunnar Lind Haase. Handbook of Social Capital: The Troika of Sociology, Political Science and Economics (англ.). — Edward Elgar Publishing (англ.)русск., 2009. — ISBN 978-1845423230.

- Zemtsov, Ilya. Chernenko: The Last Bolshevik: The Soviet Union on the Eve of Perestroika (англ.). — Transaction Publishers (англ.)русск., 1989. — ISBN 978-0887382604.

Ссылки[править | править код]

- Фактические и номинальные правители СССР

- Succession of Power in the USSR from the Dean Peter Krogh Foreign Affairs Digital Archives

- Heads of State and Government of the Soviet Union (1922–1991)

|

Communist Party of the Soviet Union Коммунистическая партия Советского Союза |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Leaders[a] | Vladimir Lenin Joseph Stalin Georgy Malenkov Nikita Khrushchev Leonid Brezhnev Yuri Andropov Konstantin Chernenko Mikhail Gorbachev Vladimir Ivashko (acting) |

| Founded | January 1912; 111 years ago[b] |

| Banned | 6 November 1991; 31 years ago[1] |

| Preceded by | Bolshevik faction of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party |

| Succeeded by | UCP–CPSU[2] |

| Headquarters | 4 Staraya Square, Moscow |

| Newspaper | Pravda[3] |

| Youth wing | Komsomol[4] |

| Women’s wing | Zhenotdel (1919–1930) |

| Pioneer wing | Young Pioneers[5] Little Octobrists |

| Military wing | Red Army (1918–1922) |

| Membership (1989 est.) | 19,487,822[6] |

| Ideology |

|

| Political position | Far-left[10][11] |

| Religion | None[12] |

| National affiliation | Bloc of Communists and Non-Partisans (1936–1991)[13][14] |

| International affiliation |

|

| Colours | Red[18] |

| Slogan | «Workers of the world, unite!»[c] |

| Anthem | «The Internationale»[d][19] «Hymn of the Bolshevik Party»[e] |

|

The Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU),[f] at some points known as the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) and All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) and sometimes referred to as the Soviet Communist Party (SCP), was the founding and ruling political party of the Soviet Union. The CPSU was the sole governing party of the Soviet Union until 1990 when the Congress of People’s Deputies modified Article 6 of the 1977 Soviet Constitution, which had previously granted the CPSU a monopoly over the political system.

The party started in 1898 as the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party. In 1903, that party split into a Menshevik (minority) and Bolshevik (majority) faction; the latter, led by Vladimir Lenin, is the direct ancestor of the CPSU and is the party that seized power in the October Revolution of 1917. Its activities were suspended on Soviet territory 74 years later, on 29 August 1991, soon after a failed coup d’état by conservative CPSU leaders against the reforming Soviet president and party general secretary Mikhail Gorbachev.

The CPSU was a communist party based on democratic centralism. This principle, conceived by Lenin, entails democratic and open discussion of policy issues within the party, followed by the requirement of total unity in upholding the agreed policies. The highest body within the CPSU was the Party Congress, which convened every five years. When the Congress was not in session, the Central Committee was the highest body. Because the Central Committee met twice a year, most day-to-day duties and responsibilities were vested in the Politburo, (previously the Presidium), the Secretariat and the Orgburo (until 1952). The party leader was the head of government and held the office of either General Secretary, Premier or head of state, or two of the three offices concurrently, but never all three at the same time. The party leader was the de facto chairman of the CPSU Politburo and chief executive of the Soviet Union. The tension between the party and the state (Council of Ministers of the Soviet Union) for the shifting focus of power was never formally resolved.

After the founding of the Soviet Union in 1922, Lenin had introduced a mixed economy, commonly referred to as the New Economic Policy, which allowed for capitalist practices to resume under the Communist Party dictation in order to develop the necessary conditions for socialism to become a practical pursuit in the economically undeveloped country. In 1929, as Joseph Stalin became the leader of the party, Marxism–Leninism, a fusion of the original ideas of German philosopher and economic theorist Karl Marx, and Lenin, became formalized as the party’s guiding ideology and would remain so throughout the rest of its existence. The party pursued state socialism, under which all industries were nationalized, and a command economy was implemented. After recovering from the Second World War, reforms were implemented which decentralized economic planning and liberalized Soviet society in general under Nikita Khrushchev. By 1980, various factors, including the continuing Cold War, and ongoing nuclear arms race with the United States and other Western European powers and unaddressed inefficiencies in the economy, led to stagnant economic growth under Alexei Kosygin, and further with Leonid Brezhnev and growing disillusionment. After the younger, vigorous Mikhail Gorbachev assumed leadership in 1985 (following two short-term elderly leaders, Yuri Andropov and Konstantin Chernenko, who quickly died in succession), rapid steps were taken to transform the tottering Soviet economic system in the direction of a market economy once again. Gorbachev and his allies envisioned the introduction of an economy similar to Lenin’s earlier New Economic Policy through a program of «perestroika», or restructuring, but their reforms, along with the institution of free multi-candidate elections led to a decline in the party’s power, and after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the banning of the party by later last RSFSR President Boris Yeltsin and subsequent first President of an evolving democratic and free-market economy of the successor Russian Federation.

A number of causes contributed to CPSU’s loss of control and the dissolution of the Soviet Union during the early 1990s. Some historians have written that Gorbachev’s policy of «glasnost» (political openness) was the root cause, noting that it weakened the party’s control over society. Gorbachev maintained that perestroika without glasnost was doomed to failure anyway. Others have blamed the economic stagnation and subsequent loss of faith by the general populace in communist ideology. In the final years of the CPSU’s existence, the Communist Parties of the federal subjects of Russia were united into the Communist Party of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR). After the CPSU’s demise, the Communist Parties of the Union Republics became independent and underwent various separate paths of reform. In Russia, the Communist Party of the Russian Federation emerged and has been regarded as the inheritor of the CPSU’s old Bolshevik legacy into the present day.[20]

History[edit]

Name[edit]

- 16 August 1917 – 8 March 1918: Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (Bolsheviks) (Russian: Российская социал-демократическая рабочая партия (большевиков); РСДРП(б), romanized: Rossiyskaya sotsial-demokraticheskaya rabochaya partiya (bol’shevikov); RSDRP(b))

- 8 March 1918 – 31 December 1925: Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) (Russian: Российская коммунистическая партия (большевиков); РКП(б), romanized: Rossiyskaya kommunisticheskaya partiya (bol’shevikov); RKP(b))

- 31 December 1925 – 14 October 1952: All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) (Russian: Всесоюзная коммунистическая партия (большевиков); ВКП(б), romanized: Vsesoyuznaya kommunisticheskaya partiya (bol’shevikov); VKP(b))

- 14 October 1952 – 6 November 1991: Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Russian: Коммунистическая партия Советского Союза; КПСС, romanized: Kommunisticheskaya partiya Sovetskogo Soyuza; KPSS)

Early years (1898–1924)[edit]

The origin of the CPSU was in the Bolshevik faction of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP). This faction arose out of the split between followers of Julius Martov and Vladimir Lenin in August 1903 at the Party’s second conference. Martov’s followers were called the Mensheviks (which means minority in Russian); and Lenin’s, the Bolsheviks (majority). (The two factions were in fact of fairly equal numerical size.) The split became more formalized in 1914, when the factions became named the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (Bolsheviks), and Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (Mensheviks). Prior to the February Revolution, the first phase of the Russian Revolutions of 1917, the party worked underground as organized anti-Tsarist groups. By the time of the revolution, many of the party’s central leaders, including Lenin, were in exile.

With Emperor Nicholas II (1868–1918, reigned 1894–1917), deposed in February 1917, a republic was established and administered by a provisional government, which was largely dominated by the interests of the military, former nobility, major capitalists business owners and democratic socialists. Alongside it, grassroots general assemblies spontaneously formed, called soviets, and a dual-power structure between the soviets and the provisional government was in place until such a time that their differences would be reconciled in a post-provisional government. Lenin was at this time in exile in Switzerland where he, with other dissidents in exile, managed to arrange with the Imperial German government safe passage through Germany in a sealed train back to Russia through the continent amidst the ongoing World War. In April, Lenin arrived in Petrograd (renamed former St. Petersburg) and condemned the provisional government, calling for the advancement of the revolution towards the transformation of the ongoing war into a war of the working class against capitalism. The rebellion proved not yet to be over, as tensions between the social forces aligned with the soviets (councils) and those with the provisional government now led by Alexander Kerensky (1881–1970, in power 1917), came into explosive tensions during that summer.

The Bolsheviks had rapidly increased their political presence from May onward through the popularity of their program, notably calling for an immediate end to the war, land reform for the peasants, and restoring food allocation to the urban population. This program was translated to the masses through simple slogans that patiently explained their solution to each crisis the revolution created. Up to July, these policies were disseminated through 41 publications, Pravda being the main paper, with a readership of 320,000. This was roughly halved after the repression of the Bolsheviks following the July Days demonstrations so that even by the end of August, the principal paper of the Bolsheviks had a print run of only 50,000 copies. Despite this, their ideas gained them increasing popularity in elections to the soviets.[21]

The factions within the soviets became increasingly polarized in the later summer after armed demonstrations by soldiers at the call of the Bolsheviks and an attempted military coup by commanding Gen. Lavr Kornilov to eliminate the socialists from the provisional government. As the general consensus within the soviets moved leftward, less militant forces began to abandon them, leaving the Bolsheviks in a stronger position. By October, the Bolsheviks were demanding the full transfer of power to the soviets and for total rejection of the Kerensky led provisional government’s legitimacy. The provisional government, insistent on maintaining the universally despised war effort on the Eastern Front because of treaty ties with its Allies and fears of Imperial German victory, had become socially isolated and had no enthusiastic support on the streets. On 7 November (25 October, old style), the Bolsheviks led an armed insurrection, which overthrew the Kerensky provisional government and left the soviets as the sole governing force in Russia.

In the aftermath of the October Revolution, the soviets united federally and the Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic, the world’s first constitutionally socialist state, was established.[22] The Bolsheviks were the majority within the soviets and began to fulfill their campaign promises by signing a damaging peace to end the war with the Germans in the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk and transferring estates and imperial lands to workers’ and peasants’ soviets.[22] In this context, in 1918, RSDLP(b) became All-Russian Communist Party (bolsheviks). Outside of Russia, social-democrats who supported the Soviet government began to identify as communists, while those who opposed it retained the social-democratic label.

In 1921, as the Civil War was drawing to a close, Lenin proposed the New Economic Policy (NEP), a system of state capitalism that started the process of industrialization and post-war recovery.[23] The NEP ended a brief period of intense rationing called «war communism» and began a period of a market economy under Communist dictation. The Bolsheviks believed at this time that Russia, being among the most economically undeveloped and socially backward countries in Europe, had not yet reached the necessary conditions of development for socialism to become a practical pursuit and that this would have to wait for such conditions to arrive under capitalist development as had been achieved in more advanced countries such as England and Germany. On 30 December 1922, the Russian SFSR joined former territories of the Russian Empire to form the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), of which Lenin was elected leader.[24] On 9 March 1923, Lenin suffered a stroke, which incapacitated him and effectively ended his role in government. He died on 21 January 1924,[24] only thirteen months after the founding of the Soviet Union, of which he would become regarded as the founding father.

Stalin era (1924–53)[edit]

After Lenin’s death, a power struggle ensued between Joseph Stalin, the party’s General Secretary, and Leon Trotsky, the Minister of Defence, each with highly contrasting visions for the future direction of the country. Trotsky sought to implement a policy of permanent revolution, which was predicated on the notion that the Soviet Union would not be able to survive in a socialist character when surrounded by hostile governments and therefore concluded that it was necessary to actively support similar revolutions in the more advanced capitalist countries. Stalin, however, argued that such a foreign policy would not be feasible with the capabilities then possessed by the Soviet Union and that it would invite the country’s destruction by engaging in armed conflict. Rather, Stalin argued that the Soviet Union should, in the meantime, pursue peaceful coexistence and invite foreign investment in order to develop the country’s economy and build socialism in one country.

Ultimately, Stalin gained the greatest support within the party, and Trotsky, who was increasingly viewed as a collaborator with outside forces in an effort to depose Stalin, was isolated and subsequently expelled from the party and exiled from the country in 1928. Stalin’s policies henceforth would later become collectively known as Stalinism. In 1925, the name of the party was changed to the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks), reflecting that the republics outside of Russia proper were no longer part of an all-encompassing Russian state. The acronym was usually transliterated as VKP(b), or sometimes VCP(b). Stalin sought to formalize the party’s ideological outlook into a philosophical hybrid of the original ideas of Lenin with orthodox Marxism into what would be called Marxism–Leninism. Stalin’s position as General Secretary became the top executive position within the party, giving Stalin significant authority over party and state policy.

By the end of the 1920s, diplomatic relations with Western countries were deteriorating to the point that there was a growing fear of another allied attack on the Soviet Union. Within the country, the conditions of the NEP had enabled growing inequalities between increasingly wealthy strata and the remaining poor. The combination of these tensions led the party leadership to conclude that it was necessary for the government’s survival to pursue a new policy that would centralize economic activity and accelerate industrialization. To do this, the first five-year plan was implemented in 1928. The plan doubled the industrial workforce, proletarianizing many of the peasants by removing them from their land and assembling them into urban centers. Peasants who remained in agricultural work were also made to have a similarly proletarian relationship to their labor through the policies of collectivization, which turned feudal-style farms into collective farms which would be in a cooperative nature under the direction of the state. These two shifts changed the base of Soviet society towards a more working-class alignment. The plan was fulfilled ahead of schedule in 1932.

The success of industrialization in the Soviet Union led Western countries, such as the United States, to open diplomatic relations with the Soviet government.[25] In 1933, after years of unsuccessful workers’ revolutions (including a short-lived Bavarian Soviet Republic) and spiraling economic calamity, Adolf Hitler came to power in Germany, violently suppressing the revolutionary organizers and posing a direct threat to the Soviet Union that ideologically supported them. The threat of fascist sabotage and imminent attack greatly exacerbated the already existing tensions within the Soviet Union and the Communist Party. A wave of paranoia overtook Stalin and the party leadership and spread through Soviet society. Seeing potential enemies everywhere, leaders of the government security apparatuses began severe crackdowns known as the Great Purge. In total, hundreds of thousands of people, many of whom were posthumously recognized as innocent, were arrested and either sent to prison camps or executed. Also during this time, a campaign against religion was waged in which the Russian Orthodox Church, which had long been a political arm of Tsarism before the revolution, was targeted for repression and organized religion was generally removed from public life and made into a completely private matter, with many churches, mosques and other shrines being repurposed or demolished.

The Soviet Union was the first to warn of the impending danger of invasion from Nazi Germany to the international community. The Western powers, however, remained committed to maintaining peace and avoiding another war breaking out, many considering the Soviet Union’s warnings to be an unwanted provocation. After many unsuccessful attempts to create an anti-fascist alliance among the Western countries, including trying to rally international support for the Spanish Republic in its struggle against a fascist military coup supported by Germany and Italy, in 1939 the Soviet Union signed a non-aggression pact with Germany which would be broken in June 1941 when the German military invaded the Soviet Union in the largest land invasion in history, beginning the Great Patriotic War.

The Communist International was dissolved in 1943 after it was concluded that such an organization had failed to prevent the rise of fascism and the global war necessary to defeat it. After the 1945 Allied victory of World War II, the Party held to a doctrine of establishing socialist governments in the post-war occupied territories that would be administered by Communists loyal to Stalin’s administration. The party also sought to expand its sphere of influence beyond the occupied territories, using proxy wars and espionage and providing training and funding to promote Communist elements abroad, leading to the establishment of the Cominform in 1947.

In 1949, the Communists emerged victorious in the Chinese Civil War, causing an extreme shift in the global balance of forces and greatly escalating tensions between the Communists and the Western powers, fueling the Cold War. In Europe, Yugoslavia, under the leadership of Josip Broz Tito, acquired the territory of Trieste, causing conflict both with the Western powers and with the Stalin administration who opposed such a provocative move. Furthermore, the Yugoslav Communists actively supported the Greek Communists during their civil war, further frustrating the Soviet government. These tensions led to a Tito–Stalin split, which marked the beginning of international sectarian division within the world communist movement.

Post-Stalin years (1953–85)[edit]

After Stalin’s death, Nikita Khrushchev rose to the top post by overcoming political adversaries, including Lavrentiy Beria and Georgy Malenkov, in a power struggle.[26] In 1955, Khrushchev achieved the demotion of Malenkov and secured his own position as Soviet leader.[27] Early in his rule and with the support of several members of the Presidium, Khrushchev initiated the Thaw, which effectively ended the Stalinist mass terror of the prior decades and reduced socio-economic oppression considerably.[28] At the 20th Congress held in 1956, Khrushchev denounced Stalin’s crimes, being careful to omit any reference to complicity by any sitting Presidium members.[29] His economic policies, while bringing about improvements, were not enough to fix the fundamental problems of the Soviet economy. The standard of living for ordinary citizens did increase; 108 million people moved into new housing between 1956 and 1965.[30]

Khrushchev’s foreign policies led to the Sino-Soviet split, in part a consequence of his public denunciation of Stalin.[31] Khrushchev improved relations with Josip Broz Tito’s League of Communists of Yugoslavia but failed to establish the close, party-to-party relations that he wanted.[30] While the Thaw reduced political oppression at home, it led to unintended consequences abroad, such as the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 and unrest in Poland, where the local citizenry now felt confident enough to rebel against Soviet control.[32] Khrushchev also failed to improve Soviet relations with the West, partially because of a hawkish military stance.[32] In the aftermath of the Cuban Missile Crisis, Khrushchev’s position within the party was substantially weakened.[33] Shortly before his eventual ousting, he tried to introduce economic reforms championed by Evsei Liberman, a Soviet economist, which tried to implement market mechanisms into the planned economy.[34]

Khrushchev was ousted on 14 October 1964 in a Central Committee plenum that officially cited his inability to listen to others, his failure in consulting with the members of the Presidium, his establishment of a cult of personality, his economic mismanagement, and his anti-party reforms as the reasons he was no longer fit to remain as head of the party.[35] He was succeeded in office by Leonid Brezhnev as First Secretary and Alexei Kosygin as Chairman of the Council of Ministers.[36]

The Brezhnev era began with a rejection of Khrushchevism in virtually every arena except one: continued opposition to Stalinist methods of terror and political violence.[38] Khrushchev’s policies were criticized as voluntarism, and the Brezhnev period saw the rise of neo-Stalinism.[39] While Stalin was never rehabilitated during this period, the most conservative journals in the country were allowed to highlight positive features of his rule.[39]

At the 23rd Congress held in 1966, the names of the office of First Secretary and the body of the Presidium reverted to their original names: General Secretary and Politburo, respectively.[40] At the start of his premiership, Kosygin experimented with economic reforms similar to those championed by Malenkov, including prioritizing light industry over heavy industry to increase the production of consumer goods.[41] Similar reforms were introduced in Hungary under the name New Economic Mechanism; however, with the rise to power of Alexander Dubček in Czechoslovakia, who called for the establishment of «socialism with a human face», all non-conformist reform attempts in the Soviet Union were stopped.[42]

During his rule, Brezhnev supported détente, a passive weakening of animosity with the West with the goal of improving political and economic relations.[43] However, by the 25th Congress held in 1976, political, economic and social problems within the Soviet Union began to mount, and the Brezhnev administration found itself in an increasingly difficult position.[44] The previous year, Brezhnev’s health began to deteriorate. He became addicted to painkillers and needed to take increasingly more potent medications to attend official meetings.[45] Because of the «trust in cadres» policy implemented by his administration, the CPSU leadership evolved into a gerontocracy.[46] At the end of Brezhnev’s rule, problems continued to amount; in 1979 he consented to the Soviet intervention in Afghanistan to save the embattled communist regime there and supported the oppression of the Solidarity movement in Poland. As problems grew at home and abroad, Brezhnev was increasingly ineffective in responding to the growing criticism of the Soviet Union by Western leaders, most prominently by US Presidents Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan, and UK Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher.[47] The CPSU, which had wishfully interpreted the financial crisis of the 1970s as the beginning of the end of capitalism, found its country falling far behind the West in its economic development.[48] Brezhnev died on 10 November 1982, and was succeeded by Yuri Andropov on 12 November.[49]

Andropov, a staunch anti-Stalinist, chaired the KGB during most of Brezhnev’s reign.[50] He had appointed several reformers to leadership positions in the KGB, many of whom later became leading officials under Gorbachev.[50] Andropov supported increased openness in the press, particularly regarding the challenges facing the Soviet Union.[51] Andropov was in office briefly, but he appointed a number of reformers, including Yegor Ligachev, Nikolay Ryzhkov and Mikhail Gorbachev, to important positions. He also supported a crackdown on absenteeism and corruption.[51] Andropov had intended to let Gorbachev succeed him in office, but Konstantin Chernenko and his supporters suppressed the paragraph in the letter which called for Gorbachev’s elevation.[51] Andropov died on 9 February 1984 and was succeeded by Chernenko.[52] The elderly Cherneko was in poor health throughout his short leadership and was unable to consolidate power; effective control of the party organization remained with Gorbachev.[52] Chernenko died on 10 March 1985 and was succeeded in. office by Gorbachev on 11 March 1985.[52]

Gorbachev and the party’s demise (1985–91)[edit]

The Politburo did not want another elderly and frail leader after its previous three leaders, and elected Gorbachev as CPSU General Secretary on 11 March 1985, one day after Chernenko’s death.[53] When Gorbachev acceded to power, the Soviet Union was stagnating but was stable and might have continued largely unchanged into the 21st century if not for Gorbachev’s reforms.[54]

Gorbachev conducted a significant personnel reshuffling of the CPSU leadership, forcing old party conservatives out of office.[55] In 1985 and early 1986 the new leadership of the party called for uskoreniye (Russian: ускоре́ние, lit. ‘acceleration’).[55] Gorbachev reinvigorated the party ideology, adding new concepts and updating older ones.[55] Positive consequences of this included the allowance of «pluralism of thought» and a call for the establishment of «socialist pluralism» (literally, socialist democracy).[56] Gorbachev introduced a policy of glasnost (Russian: гла́сность, meaning openness or transparency) in 1986, which led to a wave of unintended democratization.[57] According to the British researcher of Russian affairs, Archie Brown, the democratization of the Soviet Union brought mixed blessings to Gorbachev; it helped him to weaken his conservative opponents within the party but brought out accumulated grievances which had been suppressed during the previous decades.[57]

In reaction to these changes, a conservative movement gained momentum in 1987 in response to Boris Yeltsin’s dismissal as First Secretary of the CPSU Moscow City Committee.[58] On 13 March 1988, Nina Andreyeva, a university lecturer, wrote an article titled «I Cannot Forsake My Principles».[59] The publication was planned to occur when both Gorbachev and his protege Alexander Yakovlev were visiting foreign countries.[59] In their place, Yegor Ligachev led the party organization and told journalists that the article was «a benchmark for what we need in our ideology today».[59] Upon Gorbachev’s return, the article was discussed at length during a Politburo meeting; it was revealed that nearly half of its members were sympathetic to the letter and opposed further reforms which could weaken the party.[59] The meeting lasted for two days, but on 5 April a Politburo resolution responded with a point-by-point rebuttal to Andreyeva’s article.[59]

Gorbachev convened the 19th Party Conference in June 1988. He criticized leading party conservatives—Ligachev, Andrei Gromyko and Mikhail Solomentsev.[59] In turn, conservative delegates attacked Gorbachev and the reformers.[60] According to Brown, there had not been as much open discussion and dissent at a party meeting since the early 1920s.[60]

Despite the deep-seated opposition to further reform, the CPSU remained hierarchical; the conservatives acceded to Gorbachev’s demands in deference to his position as the CPSU General Secretary.[60] The 19th Conference approved the establishment of the Congress of People’s Deputies (CPD) and allowed for contested elections between the CPSU and independent candidates. Other organized parties were not allowed.[60] The CPD was elected in 1989; one-third of the seats were appointed by the CPSU and other public organizations to sustain the Soviet one-party state.[60] The elections were democratic, but most elected CPD members opposed any more radical reform.[61] The elections featured the highest electoral turnout in Russian history; no election before or since had a higher participation rate.[62] An organized opposition was established within the legislature under the name Inter-Regional Group of Deputies by dissident Andrei Sakharov.[62] An unintended consequence of these reforms was the increased anti-CPSU pressure; in March 1990, at a session of the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union, the party was forced to relinquish its political monopoly of power, in effect turning the Soviet Union into a liberal democracy.[63]

The CPSU’s demise began in March 1990, when state bodies eclipsed party elements in power.[63] From then until the Soviet Union’s disestablishment, Gorbachev ruled the country through the newly created post of President of the Soviet Union.[63] Following this, the central party apparatus did not play a practical role in Soviet affairs.[63] Gorbachev had become independent from the Politburo and faced few constraints from party leaders.[63] In the summer of 1990 the party convened the 28th Congress.[64] A new Politburo was elected, previous incumbents (except Gorbachev and Vladimir Ivashko, the CPSU Deputy General Secretary) were removed.[64] Later that year, the party began work on a new program with a working title, «Towards a Humane, Democratic Socialism».[64] According to Brown, the program reflected Gorbachev’s journey from an orthodox communist to a European social democrat.[64] The freedoms of thought and organization which Gorbachev allowed led to a rise in nationalism in the Soviet republics, indirectly weakening the central authorities.[65] In response to this, a referendum took place in 1991, in which most of the union republics[g] voted to preserve the union in a different form.[65] In reaction to this, conservative elements within the CPSU launched the August 1991 coup, which overthrew Gorbachev but failed to preserve the Soviet Union.[65] When Gorbachev resumed control (21 August 1991) after the coup’s collapse, he resigned from the CPSU on 24 August 1991 and operations were handed over to Ivashko.[66] On 29 August 1991 the activity of the CPSU was suspended throughout the country,[67] on 6 November Yeltsin banned the activities of the party in Russia[68] and Gorbachev resigned from the presidency on 25 December; the following day the Soviet of Republics dissolved the Soviet Union.[69]

On 30 November 1992, the Constitutional Court of the Russian Federation recognized the ban on the activities of the primary organizations of the Communist Party, formed on a territorial basis, as inconsistent with the Constitution of Russia, but upheld the dissolution of the governing structures of the CPSU and the governing structures of its republican organization—the Communist Party of the RSFSR.[70]

After the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, Russian adherents to the CPSU tradition, particularly as it existed before Gorbachev, reorganized themselves within the Communist Party of the Russian Federation (CPRF). Today a wide range of parties in Russia present themselves as successors of CPSU. Several of them have used the name «CPSU». However, the CPRF is generally seen (due to its massive size) as the heir of the CPSU in Russia. Additionally, the CPRF was initially founded as the Communist Party of the Russian SFSR in 1990 (sometime before the abolition of the CPSU) and was seen by critics as a «Russian-nationalist» counterpart to the CPSU.[citation needed]

Governing style[edit]

The style of governance in the party alternated between collective leadership and a cult of personality. Collective leadership split power between the Politburo, the Central Committee, and the Council of Ministers to hinder any attempts to create a one-man dominance over the Soviet political system. By contrast, Stalin’s period as the leader was characterized by an extensive cult of personality. Regardless of leadership style, all political power in the Soviet Union was concentrated in the organization of the CPSU.

Democratic centralism[edit]

Democratic centralism is an organizational principle conceived by Lenin.[71] According to Soviet pronouncements, democratic centralism was distinguished from «bureaucratic centralism», which referred to high-handed formulae without knowledge or discussion.[71] In democratic centralism, decisions are taken after discussions, but once the general party line has been formed, discussion on the subject must cease.[71] No member or organizational institution may dissent on a policy after it has been agreed upon by the party’s governing body; to do so would lead to expulsion from the party (formalized at the 10th Congress).[71] Because of this stance, Lenin initiated a ban on factions, which was approved at the 10th Congress.[72]

Lenin believed that democratic centralism safeguarded both party unity and ideological correctness.[71] He conceived of the system after the events of 1917 when several socialist parties «deformed» themselves and actively began supporting nationalist sentiments.[73] Lenin intended that the devotion to policy required by centralism would protect the parties from such revisionist ills and bourgeois deformation of socialism.[73] Lenin supported the notion of a highly centralized vanguard party, in which ordinary party members elected the local party committee, the local party committee elected the regional committee, the regional committee elected the Central Committee, and the Central Committee elected the Politburo, Orgburo, and the Secretariat.[71] Lenin believed that the party needed to be ruled from the center and have at its disposal power to mobilize party members at will.[71] This system was later introduced in communist parties abroad through the Communist International (Comintern).[72]

Vanguardism[edit]

A central tenet of Leninism was that of the vanguard party.[74] In a capitalist society, the party was to represent the interests of the working class and all of those who were exploited by capitalism in general; however, it was not to become a part of that class.[74] Lenin decided that the party’s sole responsibility was to articulate and plan the long-term interests of the oppressed classes. It was not responsible for the daily grievances of those classes; that was the responsibility of the trade unions.[74] According to Lenin, the party and the oppressed classes could never become one because the party was responsible for leading the oppressed classes to victory.[75] The basic idea was that a small group of organized people could wield power disproportionate to their size with superior organizational skills.[75] Despite this, until the end of his life, Lenin warned of the danger that the party could be taken over by bureaucrats, by a small clique, or by an individual.[75] Toward the end of his life, he criticized the bureaucratic inertia of certain officials and admitted to problems with some of the party’s control structures, which were to supervise organizational life.[75]

Organization[edit]

|

|

Congress[edit]

The Congress, nominally the highest organ of the party, was convened every five years.[76] Leading up to the October Revolution and until Stalin’s consolidation of power, the Congress was the party’s main decision-making body.[77] However, after Stalin’s ascension, the Congresses became largely symbolic.[77] CPSU leaders used Congresses as a propaganda and control tool.[77] The most noteworthy Congress since the 1930s was the 20th Congress, in which Khrushchev denounced Stalin in a speech titled «The Personality Cult and its Consequences».[77]

Despite delegates to Congresses losing their powers to criticize or remove party leadership, the Congresses functioned as a form of elite-mass communication.[78] They were occasions for the party leadership to express the party line over the next five years to ordinary CPSU members and the general public.[78] The information provided was general, ensuring that party leadership retained the ability to make specific policy changes as they saw fit.[78]

The Congresses also provided the party leadership with formal legitimacy by providing a mechanism for the election of new members and the retirement of old members who had lost favor.[79] The elections at Congresses were all predetermined and the candidates who stood for seats to the Central Committee and the Central Auditing Commission were approved beforehand by the Politburo and the Secretariat.[79] A Congress could also provide a platform for the announcement of new ideological concepts.[79] For instance, at the 22nd Congress, Khrushchev announced that the Soviet Union would see «communism in twenty years»—[80] a position later retracted.

A Conference, officially referred to as an All-Union Conference, was convened between Congresses by the Central Committee to discuss party policy and to make personnel changes within the Central Committee.[81] 19 conferences were convened during the CPSU’s existence.[81] The 19th Congress held in 1952 removed the clause in the party’s statute which stipulated that a party Conference could be convened.[81] The clause was reinstated at the 23rd Congress, which was held in 1966.[81]

Central Committee[edit]

The Central Committee was a collective body elected at the annual party congress.[82] It was mandated to meet at least twice a year to act as the party’s supreme governing body.[82] Membership of the Central Committee increased from 71 full members in 1934 to 287 in 1976.[83] Central Committee members were elected to the seats because of the offices they held, not on their personal merit.[84] Because of this, the Central Committee was commonly considered an indicator for Sovietologists to study the strength of the different institutions.[84] The Politburo was elected by and reported to the Central Committee.[85] Besides the Politburo, the Central Committee also elected the Secretariat and the General Secretary—the de facto leader of the Soviet Union.[85] In 1919–1952, the Orgburo was also elected in the same manner as the Politburo and the Secretariat by the plenums of the Central Committee.[85] In between Central Committee plenums, the Politburo and the Secretariat were legally empowered to make decisions on its behalf.[85] The Central Committee or the Politburo and/or Secretariat on its behalf could issue nationwide decisions; decisions on behalf of the party were transmitted from the top to the bottom.[86]

Under Lenin, the Central Committee functioned much as the Politburo did during the post-Stalin era, serving as the party’s governing body.[87] However, as the membership in the Central Committee increased, its role was eclipsed by the Politburo.[87] Between Congresses, the Central Committee functioned as the Soviet leadership’s source of legitimacy.[87] The decline in the Central Committee’s standing began in the 1920s; it was reduced to a compliant body of the Party leadership during the Great Purge.[87] According to party rules, the Central Committee was to convene at least twice a year to discuss political matters—but not matters relating to military policy.[88] The body remained largely symbolic after Stalin’s consolidation; leading party officials rarely attended meetings of the Central Committee.[89]

Central Auditing Commission[edit]

The Central Auditing Commission (CAC) was elected by the party Congresses and reported only to the party Congress.[90] It had about as many members as the Central Committee.[90] It was responsible for supervising the expeditious and proper handling of affairs by the central bodies of the Party; it audited the accounts of the Treasury and the enterprises of the Central Committee.[90] It was also responsible for supervising the Central Committee apparatus, making sure that its directives were implemented and that Central Committee directives complied with the party Statute.[90]

Statute[edit]

The Statute (also referred to as the Rules, Charter and Constitution) was the party’s by-laws and controlled life within the CPSU.[91] The 1st Statute was adopted at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party—the forerunner of the CPSU.[91] How the Statute was to be structured and organized led to a schism within the party, leading to the establishment of two competing factions; Bolsheviks (literally majority) and Mensheviks (literally minority).[91] The 1st Statute was based upon Lenin’s idea of a centralized vanguard party.[91] The 4th Congress, despite a majority of Menshevik delegates, added the concept of democratic centralism to Article 2 of the Statute.[92] The 1st Statute lasted until 1919 when the 8th Congress adopted the 2nd Statute.[93] It was nearly five times as long as the 1st Statute and contained 66 articles.[93] It was amended at the 9th Congress. At the 11th Congress, the 3rd Statute was adopted with only minor amendments being made.[94] New statutes were approved at the 17th and 18th Congresses respectively.[95] The last party statute, which existed until the dissolution of the CPSU, was adopted at the 22nd Congress.[96]

Central Committee apparatus[edit]

General Secretary[edit]

General Secretary of the Central Committee was the title given to the overall leader of the party. The office was synonymous with the leader of the Soviet Union after Joseph Stalin’s consolidation of power in the 1920s. Stalin used the office of General Secretary to create a strong power base for himself. The office was formally titled First Secretary between 1953 and 1966.

Politburo[edit]

The Political Bureau (Politburo), known as the Presidium from 1952 to 1966, was the highest party organ when the Congress and the Central Committee were not in session.[97] Until the 19th Conference in 1988, the Politburo alongside the Secretariat controlled appointments and dismissals nationwide.[98] In the post-Stalin period, the Politburo controlled the Central Committee apparatus through two channels; the General Department distributed the Politburo’s orders to the Central Committee departments and through the personnel overlap which existed within the Politburo and the Secretariat.[98] This personnel overlap gave the CPSU General Secretary a way of strengthening his position within the Politburo through the Secretariat.[99] Kirill Mazurov, Politburo member from 1965 to 1978, accused Brezhnev of turning the Politburo into a «second echelon» of power.[99] He accomplished this by discussing policies before Politburo meetings with Mikhail Suslov, Andrei Kirilenko, Fyodor Kulakov and Dmitriy Ustinov among others, who held seats both in the Politburo and the Secretariat.[99] Mazurov’s claim was later verified by Nikolai Ryzhkov, the Chairman of the Council of Ministers under Gorbachev. Ryzhkov said that Politburo meetings lasted only 15 minutes because the people close to Brezhnev had already decided what was to be approved.[99]

The Politburo was abolished and replaced by a Presidium in 1952 at the 19th Congress.[100] In the aftermath the 19th Congress and the 1st Plenum of the 19th Central Committee, Stalin ordered the creation of the Bureau of the Presidium, which acted as the standing committee of the Presidium.[101] On 6 March 1953, one day after Stalin’s death, a new and smaller Presidium was elected, and the Bureau of the Presidium was abolished in a joint session with the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet and the Council of Ministers.[102]

Until 1990, the CPSU General Secretary acted as the informal chairman of the Politburo.[103] During the first decades of the CPSU’s existence, the Politburo was officially chaired by the Chairman of the Council of People’s Commissars; first by Lenin, then by Aleksey Rykov, Molotov, Stalin and Malenkov.[103] After 1922, when Lenin was incapacitated, Lev Kamenev as Deputy Chairman of the Council of People’s Commissars chaired the Politburo’s meetings.[103] This tradition lasted until Khrushchev’s consolidation of power.[103] In the first post-Stalin years, when Malenkov chaired Politburo meetings, Khrushchev as First Secretary signed all Central Committee documents into force.[103] From 1954 until 1958, Khrushchev chaired the Politburo as First Secretary, but in 1958 he dismissed and succeeded Nikolai Bulganin as Chairman of the Council of Ministers.[104] During this period, the informal position of Second Secretary—later formalized as Deputy General Secretary—was established.[104] The Second Secretary became responsible for chairing the Secretariat in place of the General Secretary. When the General Secretary could not chair the meetings of the Politburo, the Second Secretary would take his place.[104] This system survived until the dissolution of the CPSU in 1991.[104]

To be elected to the Politburo, a member had to serve in the Central Committee.[105] The Central Committee elected the Politburo in the aftermath of a party Congress.[105] Members of the Central Committee were given a predetermined list of candidates for the Politburo having only one candidate for each seat; for this reason, the election of the Politburo was usually passed unanimously.[105] The greater the power held by the sitting CPSU General Secretary, the higher the chance that the Politburo membership would be approved.[105]

Secretariat[edit]

The Secretariat headed the CPSU’s central apparatus and was solely responsible for the development and implementation of party policies.[106] It was legally empowered to take over the duties and functions of the Central Committee when it was not in the plenum (did not hold a meeting).[106] Many members of the Secretariat concurrently held a seat in the Politburo.[107] According to a Soviet textbook on party procedures, the Secretariat’s role was that of «leadership of current work, chiefly in the realm of personnel selection and in the organization of the verification of fulfillment of party-state decisions».[107] «Selections of personnel» (Russian: podbor kadrov) in this instance meant the maintenance of general standards and the criteria for selecting various personnel. «Verification of fulfillment» (Russian: proverka ispolneniia) of party and state decisions meant that the Secretariat instructed other bodies.[108]

The powers of the Secretariat were weakened under Mikhail Gorbachev, and the Central Committee Commissions took over the functions of the Secretariat in 1988.[109] Yegor Ligachev, a Secretariat member, said that the changes completely destroyed the Secretariat’s hold on power and made the body almost superfluous.[109] Because of this, the Secretariat rarely met during the next two years.[109] It was revitalized at the 28th Party Congress in 1990, and the Deputy General Secretary became the official head of the Secretariat.[110]

Orgburo[edit]

The Organizational Bureau, or Orgburo, existed from 1919 to 1952 and was one of three leading bodies of the party when the Central Committee was not in session.[97] It was responsible for «organizational questions, the recruitment, and allocation of personnel, the coordination of activities of the party, government and social organizations (e.g., trade unions and youth organizations), improvement to the party’s structure, the distribution of information and reports within the party».[105] The 19th Congress abolished the Orgburo and its duties and responsibilities were taken over by the Secretariat.[105] At the beginning, the Orgburo held three meetings a week and reported to the Central Committee every second week.[111] Lenin described the relation between the Politburo and the Orgburo as «the Orgburo allocates forces, while the Politburo decides policy».[112] A decision of the Orgburo was implemented by the Secretariat.[112] However, the Secretariat could make decisions in the Orgburo’s name without consulting its members, but if one Orgburo member objected to a Secretariat resolution, the resolution would not be implemented.[112] In the 1920s, if the Central Committee could not convene the Politburo and the Orgburo would hold a joint session in its place.[112]

Control Commission[edit]

The Central Control Commission (CCC) functioned as the party’s supreme court.[113] The CCC was established at the 9th All-Russian Conference in September 1920, but rules organizing its procedure were not enacted before the 10th Congress.[114] The 10th Congress formally established the CCC on all party levels and stated that it could only be elected at a party congress or a party conference.[114] The CCC and the CCs were formally independent but had to make decisions through the party committees at their level, which led them in practice to lose their administrative independence.[114] At first, the primary responsibility of the CCs was to respond to party complaints, focusing mostly on party complaints of factionalism and bureaucratism.[115] At the 11th Congress, the brief of the CCs was expanded; it became responsible for overseeing party discipline.[116] In a bid to further centralize the powers of the CCC, a Presidium of the CCC, which functioned in a similar manner to the Politburo in relation to the Central Committee, was established in 1923.[117] At the 18th Congress, party rules regarding the CCC were changed; it was now elected by the Central Committee and was subordinate to the Central Committee.[118]

CCC members could not concurrently be members of the Central Committee.[119] To create an organizational link between the CCC and other central-level organs, the 9th All-Russian Conference created the joint CC–CCC plenums.[119] The CCC was a powerful organ; the 10th Congress allowed it to expel full and candidate Central Committee members and members of their subordinate organs if two-thirds of attendants at a CC–CCC plenum voted for such.[119] At its first such session in 1921, Lenin tried to persuade the joint plenum to expel Alexander Shliapnikov from the party; instead of expelling him, Shliapnikov was given a severe reprimand.[119]

Departments[edit]

The leader of a department was usually given the title «head» (Russian: zaveduiuschchii).[120] In practice, the Secretariat had a major say in the running of the departments; for example, five of eleven secretaries headed their own departments in 1978.[121] Normally, specific secretaries were given supervising duties over one or more departments.[121] Each department established its own cells—called sections—which specialized in one or more fields.[122] During the Gorbachev era, a variety of departments made up the Central Committee apparatus.[123] The Party Building and Cadre Work Department assigned party personnel in the nomenklatura system.[123] The State and Legal Department supervised the armed forces, KGB, the Ministry of Internal Affairs, the trade unions, and the Procuracy.[123] Before 1989, the Central Committee had several departments, but some were abolished that year.[123] Among these departments was the Economics Department that was responsible for the economy as a whole, one for machine building, one for the chemical industry, etc.[123] The party abolished these departments to remove itself from the day-to-day management of the economy in favor of government bodies and a greater role for the market, as a part of the perestroika process.[123] In their place, Gorbachev called for the creations of commissions with the same responsibilities as departments, but giving more independence from the state apparatus. This change was approved at the 19th Conference, which was held in 1988.[124] Six commissions were established by late 1988.[124]

Pravda[edit]

Pravda (The Truth) was the leading newspaper in the Soviet Union.[125] The Organizational Department of the Central Committee was the only organ empowered to dismiss Pravda editors.[126] In 1905, Pravda began as a project by members of the Ukrainian Social Democratic Labour Party.[127] Leon Trotsky was approached about the possibility of running the new paper because of his previous work on Ukrainian newspaper Kyivan Thought.[127] The first issue of Pravda was published on 3 October 1908[127] in Lvov, where it continued until the publication of the sixth issue in November 1909, when the operation was moved to Vienna, Austria-Hungary.[127] During the Russian Civil War, sales of Pravda were curtailed by Izvestia, the government run newspaper.[128] At the time, the average reading figure for Pravda was 130,000.[128] This Vienna-based newspaper published its last issue in 1912 and was succeeded the same year by a new newspaper dominated by the Bolsheviks, also called Pravda, which was headquartered in St. Petersburg.[129] The paper’s main goal was to promote Marxist–Leninist philosophy and expose the lies of the bourgeoisie.[130] In 1975, the paper reached a circulation of 10.6 million.[130] It is currently owned by the Communist Party of the Russian Federation.

Higher Party School[edit]

The Higher Party School (HPS) was the organ responsible for teaching cadres in the Soviet Union.[131] It was the successor of the Communist Academy, which was established in 1918.[131] The HPS was established in 1939 as the Moscow Higher Party School and it offered its students a two-year training course for becoming a CPSU official.[132] It was reorganized in 1956 to that it could offer more specialized ideological training.[132] In 1956, the school in Moscow was opened for students from socialist countries outside the Soviet Union.[132] The Moscow Higher Party School was the party school with the highest standing.[132] The school itself had eleven faculties until a 1972 Central Committee resolution demanded a reorganization of the curriculum.[133] The first regional HPS outside Moscow was established in 1946[133] and by the early 1950s there were 70 Higher Party Schools.[133] During the reorganization drive of 1956, Khrushchev closed 13 of them and reclassified 29 as inter-republican and inter-oblast schools.[133]

Lower-level organization[edit]

Republican and local organization[edit]

The lowest organ above the primary party organization (PPO) was the district level.[134] Every two years, the local PPO would elect delegates to the district-level party conference, which was overseen by a secretary from a higher party level. The conference elected a Party Committee and First Secretary and re-declared the district’s commitment to the CPSU’s program.[134] In between conferences, the «raion» party committee—commonly referred to as «raikom»—was vested with ultimate authority.[134] It convened at least six times a year to discuss party directives and to oversee the implementation of party policies in their respective districts, to oversee the implementation of party directives at the PPO-level, and to issue directives to PPOs.[134] 75–80 percent of raikom members were full members, while the remaining 20–25 were non-voting, candidate members.[134] Raikom members were commonly from the state sector, party sector, Komsomol or the trade unions.[134]

Day-to-day responsibility of the raikom was handed over to a Politburo, which usually composed of 12 members.[134] The district-level First Secretary chaired the meetings of the local Politburo and the raikom, and was the direct link between the district and the higher party echelons.[134] The First Secretary was responsible for the smooth running of operations.[134] The raikom was headed by the local apparat—the local agitation department or industry department.[135] A raikom usually had no more than 4 or 5 departments, each of which was responsible for overseeing the work of the state sector but would not interfere in their work.[135]

This system remained identical at all other levels of the CPSU hierarchy.[135] The other levels were cities, oblasts (regions) and republics.[135] The district-level elected delegates to a conference held at least every three years to elect the party committee.[135] The only difference between the oblast and the district level was that the oblast had its own Secretariat and had more departments at its disposal.[135] The oblast’s party committee in turn elected delegates to the republican-level Congress, which was held every five years.[136] The Congress then elected the Central Committee of the republic, which in turn elected a First Secretary and a Politburo.[136] Until 1990, the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic was the only republic that did not have its own republican branch, being instead represented by the CPSU Central Committee.

Primary party organizations[edit]

The primary party organization (PPO) was the lowest level in the CPSU hierarchy.[137] PPOs were organized cells consisting of three or more members.[137] A PPO could exist anywhere; for example, in a factory or a student dormitory.[137] They functioned as the party’s «eyes and ears» at the lowest level and were used to mobilize support for party policies.[137] All CPSU members had to be a member of a local PPO.[138] The size of a PPO varied from three people to several hundred, depending upon its setting.[138] In a large enterprise, a PPO usually had several hundred members.[138] In such cases, the PPO was divided into bureaus based upon production-units.[138] Each PPO was led by an executive committee and an executive committee secretary.[138] Each executive committee is responsible for the PPO executive committee and its secretary.[138] In small PPOs, members met periodically to mainly discuss party policies, ideology, or practical matters. In such a case, the PPO secretary was responsible for collecting party dues, reporting to higher organs, and maintaining the party records.[138] A secretary could be elected democratically through a secret ballot, but that was not often the case; in 1979, only 88 out of the over 400,000 PPOs were elected in this fashion.[138] The remainder were chosen by a higher party organ and ratified by the general meetings of the PPO.[138] The PPO general meeting was responsible for electing delegates to the party conference at either the district- or town-level, depending on where the PPO was located.[139]

Membership[edit]

Membership of the party was not open. To become a party member, one had to be approved by various committees, and one’s past was closely scrutinized. As generations grew up having known nothing before the Soviet Union, party membership became something one generally achieved after passing a series of stages. Children would join the Young Pioneers and, at the age of 14, might graduate to the Komsomol (Young Communist League). Ultimately, as an adult, if one had shown the proper adherence to party discipline—or had the right connections, one would become a member of the Communist Party itself. Membership of the party carried obligations as it expected Komsomol and CPSU members to pay dues and to carry out appropriate assignments and «social tasks» (общественная работа).[citation needed]

In 1918, party membership was approximately 200,000. In the late 1920s under Stalin, the party engaged in an intensive recruitment campaign, the «Lenin Levy», resulting in new members referred to as the Lenin Enrolment,[140] from both the working class and rural areas. This represented an attempt to «proletarianize» the party and an attempt by Stalin to strengthen his base by outnumbering the Old Bolsheviks and reducing their influence in the Party. In 1925, the party had 1,025,000 members in a Soviet population of 147 million. In 1927, membership had risen to 1,200,000. During the collectivization campaign and industrialization campaigns of the first five-year plan from 1929 to 1933, party membership grew rapidly to approximately 3.5 million members. However, party leaders suspected that the mass intake of new members had allowed «social-alien elements» to penetrate the party’s ranks and document verifications of membership ensued in 1933 and 1935, removing supposedly unreliable members. Meanwhile, the party closed its ranks to new members from 1933 to November 1936. Even after the reopening of party recruiting, membership fell to 1.9 million by 1939.[citation needed] Nicholas DeWitt gives 2.307 million members in 1939, including candidate members, compared with 1.535 million in 1929 and 6.3 million in 1947. In 1986, the CPSU had over 19 million members—approximately 10% of the Soviet Union’s adult population. Over 44% of party members were classified as industrial workers and 12% as collective farmers. The CPSU had party organizations in 14 of the Soviet Union’s 15 republics. The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic itself had no separate Communist Party until 1990 because the CPSU controlled affairs there directly.[citation needed]

Komsomol[edit]

The All-Union Leninist Communist Youth League, commonly referred to as Komsomol, was the party’s youth wing.[141] The Komsomol acted under the direction of the CPSU Central Committee.[141] It was responsible for indoctrinating youths in communist ideology and organizing social events.[142] It was closely modeled on the CPSU; nominally the highest body was the Congress, followed by the Central Committee, Secretariat and the Politburo.[141] The Komsomol participated in nationwide policy-making by appointing members to the collegiums of the Ministry of Culture, the Ministry of Higher and Specialized Secondary Education, the Ministry of Education and the State Committee for Physical Culture and Sports.[141] The organization’s newspaper was the Komsomolskaya Pravda.[143] The First Secretary and the Second Secretary were commonly members of the Central Committee but were never elected to the Politburo.[143] However, at the republican level, several Komsomol first secretaries were appointed to the Politburo.[143]

Ideology[edit]

Marxism–Leninism[edit]

Marxism–Leninism was the cornerstone of Soviet ideology.[7] It explained and legitimized the CPSU’s right to rule while explaining its role as a vanguard party.[7] For instance, the ideology explained that the CPSU’s policies, even if they were unpopular, were correct because the party was enlightened.[7] It was represented as the only truth in Soviet society; the party rejected the notion of multiple truths.[7] Marxism–Leninism was used to justify CPSU rule and Soviet policy, but it was not used as a means to an end.[7] The relationship between ideology and decision-making was at best ambivalent; most policy decisions were made in the light of the continued, permanent development of Marxism–Leninism.[144] Marxism–Leninism as the only truth could not—by its very nature—become outdated.[144]

Despite having evolved over the years, Marxism–Leninism had several central tenets.[145] The main tenet was the party’s status as the sole ruling party.[145] The 1977 Constitution referred to the party as «The leading and guiding force of Soviet society, and the nucleus of its political system, of all state and public organizations, is the Communist Party of the Soviet Union».[145] State socialism was essential and from Stalin until Gorbachev, official discourse considered that private social and economic activity retarding the development of collective consciousness and the economy.[146] Gorbachev supported privatization to a degree but based his policies on Lenin’s and Nikolai Bukharin’s opinions of the New Economic Policy of the 1920s, and supported complete state ownership over the commanding heights of the economy.[146] Unlike liberalism, Marxism–Leninism stressed the role of the individual as a member of a collective rather than the importance of the individual.[146] Individuals only had the right to freedom of expression if it safeguarded the interests of a collective.[146] For instance, the 1977 Constitution stated that every person had the right to express his or her opinion, but the opinion could only be expressed if it was in accordance with the «general interests of Soviet society».[146] The number of rights granted to an individual was decided by the state, and the state could remove these rights if it saw fit.[146] Soviet Marxism–Leninism justified nationalism; the Soviet media portrayed every victory of the state as a victory for the communist movement as a whole.[146] Largely, Soviet nationalism was based upon ethnic Russian nationalism.[146] Marxism–Leninism stressed the importance of the worldwide conflict between capitalism and socialism; the Soviet press wrote about progressive and reactionary forces while claiming that socialism was on the verge of victory and that the «correlations of forces» were in the Soviet Union’s favor.[146] The ideology professed state atheism and party members were consequently not allowed to be religious.[147]

Marxism–Leninism believed in the feasibility of a communist mode of production. All policies were justifiable if it contributed to the Soviet Union’s achievement of that stage.[148]

Leninism[edit]

In Marxist philosophy, Leninism is the body of political theory for the democratic organization of a revolutionary vanguard party and the achievement of a dictatorship of the proletariat as a political prelude to the establishment of the socialist mode of production developed by Lenin.[149] Since Karl Marx rarely, if ever wrote about how the socialist mode of production would function, these tasks were left for Lenin to solve.[149] Lenin’s main contribution to Marxist thought is the concept of the vanguard party of the working class.[149] He conceived the vanguard party as a highly knit, centralized organization that was led by intellectuals rather than by the working class itself.[149] The CPSU was open only to a small number of workers because the workers in Russia still had not developed class consciousness and needed to be educated to reach such a state.[149] Lenin believed that the vanguard party could initiate policies in the name of the working class even if the working class did not support them. The vanguard party would know what was best for the workers because the party functionaries had attained consciousness.[149]

Lenin, in light of the Marx’s theory of the state (which views the state as an oppressive organ of the ruling class), had no qualms of forcing change upon the country.[149] He viewed the dictatorship of the proletariat, rather than the dictatorship of the bourgeoisie, to be the dictatorship of the majority.[149] The repressive powers of the state were to be used to transform the country, and to strip of the former ruling class of their wealth.[149] Lenin believed that the transition from the capitalist mode of production to the socialist mode of production would last for a long period.[150] According to some authors, Leninism was by definition authoritarian.[149] In contrast to Marx, who believed that the socialist revolution would comprise and be led by the working class alone, Lenin argued that a socialist revolution did not necessarily need to be led or to comprise the working class alone. Instead, he said that a revolution needed to be led by the oppressed classes of society, which in the case of Russia was the peasant class.[151]

Stalinism[edit]