Подготовлено на основе исследований Дэниела Гоулмана (Daniel Goleman) — сопредседателья Консорциума по исследованию эмоционального интеллекта в организациях в Rogers State University

Менеджерам очень сложно оценить степень влияния рабочей атмосферы на финансовые результаты компании. Исследования показали, что внутренняя атмосфера организации практически на 30% определяет ее коммерческие результаты. Внутренний климат организации во многом определяется стилем управления, которым менеджеры «мотивируют» своих подчиненных, ставят задачи, собирают информацию, принимают решения и решают проблемы.

Существует 6 базовых стилей управления. Каждый стиль определяется различными элементами эмоционального интеллекта; лучше всего работает в определенных ситуациях; по-разному влияет на атмосферу в организации.

1. Авторитарный (или диктаторский) стиль.

Почти как в армии, требует немедленного повиновения — «Делайте как я вам сказал!». Руководитель спускает распоряжения на подчиненных, а подчиненные строго их выполняют. Авторитарный руководитель говорит подчиненным «что» делать и «как» делать.

Тут нет простора для творчества, дискуссий и обсуждений. Такой стиль управления сильно снижает мотивацию.

Авторитарный стиль применим в кризисных ситуациях, реорганизации, когда у руководителя нет взаимопонимания с сотрудниками.

Общее воздействие на атмосферу внутри коллектива – разрушительное.

2. Авторитетный стиль

Руководитель мобилизует и вдохновляет сотрудников на воплощение своих замыслов. Он формулирует конечную цель, но предоставляет подчиненным достаточную свободу действий для достижения цели.

Руководитель авторитетного стиля говорит подчиненным «что» нужно делать, а «как делать» — чаще всего сотрудники решают сами. Такому руководителю доверяют, уважают, хотят за ним следовать.

Авторитетный стиль применим в ситуациях, когда бизнес находится в тупике или стагнации, для перемен требуются новые идеи, новый стратегический курс.

Такой стиль не очень подходит, когда команда с которой работает авторитетный лидер более экспертна и профессиональна, чем руководитель.

Общее воздействие на атмосферу внутри коллектива – максимально положительное.

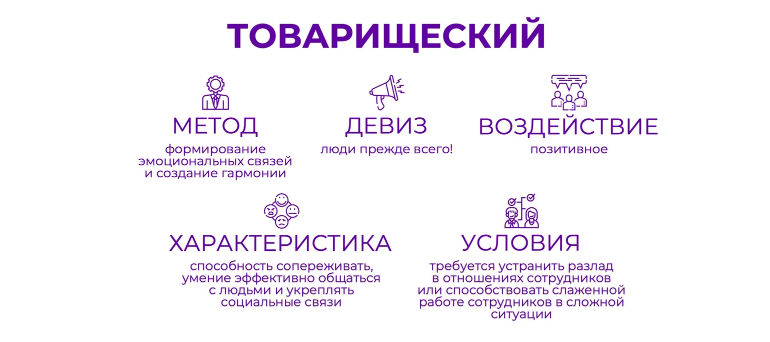

3. Дружественный стиль

Девиз такого руководителя- «Мои сотрудники это главное!» Руководитель формирует эмоциональные связи и создает внутри коллектива атмосферу мира и гармонии. Поддерживает приятельские или даже дружеские отношения с подчиненными, вместе проводят свободное время, ходят в рестораны и т.д.

В ситуациях, когда подчиненный допустил ошибку, руководитель поддерживает и подбадривает, но редко дает объективную и развивающую обратную связь, чтобы не испортить отношения – это большой минус. Поэтому некоторые результаты могут быть слабые и работники решат, что посредственность в такой организации вполне допустима.

Руководители такого типа редко дают конструктивные советы и при возникновении трудностей сотрудники остаются со своей проблемой один на один, без помощи руководства.

Применим в ситуациях, когда требуется поднять моральный дух, наладить общение и устранить разлад между сотрудниками, восстановить утраченное доверие или заставить подчиненных много работать в сложных обстоятельствах.

Общее воздействие на атмосферу внутри коллектива –положительное.

4. Демократический стиль

Выслушать все мнения и принять коллективное решение. При использовании данного стиля в организации проводится большое кол-во совещаний, которые способствуют большому количеству новых идей.

Негативная сторона– постоянные совещания и запутавшиеся сотрудники, которым сложно выработать единое мнение и принять общее решение. Это приводит к неразберихе, а сотрудникам кажется, что ими никто не руководит.

Демократический стиль применим в обстоятельствах, когда необходимо убедить работников в правилах корпоративной политики, добиться общего видения и понимания, узнать идеи сотрудников.

Общее воздействие на атмосферу внутри коллектива –положительное (но не сверх положительное, как может казаться).

5. Образцовый стиль

Девиз такого руководителя «Мы должны быть лучшими во всем!». Руководитель устанавливает крайне высокие стандарты производительности и сам им следует. Нанимает целеустремленных высокопрофессиональных сотрудников с высокой мотивацией, хорошо ладит с такими сотрудниками и выжимает из них максимум.

Остальные (сотрудники среднего уровня, а таких большинство) чувствуют себя неспособными справиться с требованиями руководителя, они выматываются и их моральный дух падает.

Образцовый стиль применим в обстоятельствах, когда нужно добиться быстрого выполнения работы.

Общее воздействие на атмосферу внутри коллектива –разрушительное.

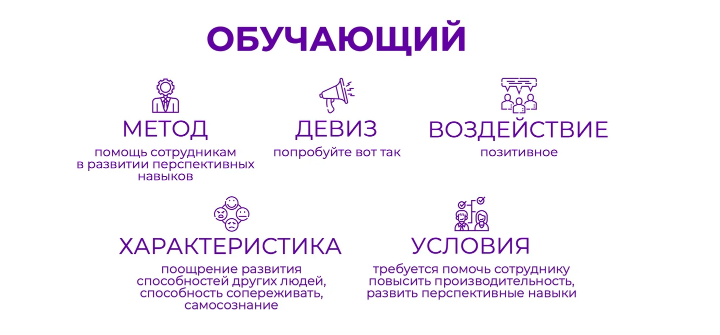

6. Обучающий стиль

Один из самых редких стилей управления, при этом один из самых сильных. Руководитель, в первую очередь уделяет внимание индивидуальному развитию подчиненных, а уже потом выполнению ими текущих рабочих задач. Определяет сильные и слабые стороны сотрудников, делегирует дела, которые способствуют развитию их перспективных способностей.

Руководитель как бы говорит: «я верю в тебя, вкладываю в твой талант и рассчитываю на исключительные усилия с твоей стороны».

Обучающий стиль эффективен, если сотрудники стремятся к развитию, понимают свои слабые стороны. И не подойдет, если подчиненные не хотят перемен и не хотят развиваться лично и профессионально.

Стиль применим в ситуациях, когда сотруднику требуется помочь повысить производительность или развить перспективные качества, умения и навыки.

Общее воздействие на атмосферу внутри коллектива –положительное.

Связь стилей управления с эмоциональным интеллектом руководителя

Многие считают, что стиль управления соответствует особенностям личности и не является результатом осознанного стратегического выбора руководителя. Но это не так.

Согласно исследованиям Дэниела Гоулмана, каждый стиль лидерства определяется различными доминирующими характеристиками эмоционального интеллекта, а его как известно, можно развивать.

1. Авторитарный стиль. Доминирующие характеристики эмоционального интеллекта:

-

инициативность

-

самоконтроль

- воля к достижению цели

2. Авторитетный стиль. Доминирующие характеристики эмоционального интеллекта:

-

уверенность в себе

-

способность сопереживать

- умение внедрять нововведения

3. Дружественный стиль. Доминирующие характеристики эмоционального интеллекта:

-

способность сопереживать

-

умение налаживать социальные связи

- эффективно общаться с людьми

4. Демократический стиль. Доминирующие характеристики эмоционального интеллекта:

-

умение грамотно взаимодействовать с другими сотрудниками

-

руководить работой команды

- эффективно общаться с людьми

5. Образцовый стиль. Доминирующие характеристики эмоционального интеллекта:

-

добросовестность

-

воля к достижениям

- инициативность

6. Обучающий стиль. Доминирующие характеристики эмоционального интеллекта:

-

поощрение развития способностей других людей

- способность сопереживать

- самосознание

Лучшие руководители не ограничиваются одним стилем управления, они сильны в нескольких, сочетают их в зависимости от ситуации, постоянно развиваются, а недостающие и слабые стороны восполняют другими членами команды.

Такой подход создает наилучший организационный климат, что способствует повышению эффективности бизнеса до 30%.

Исследования показали, что наиболее успешные управленцы наиболее сильны в следующих проявлениях эмоционального интеллекта:

-

Мотивация

- Эмпатия

- Коммуникабельность

- Способность к самоанализу

- Способность к саморегуляции

Иван Корчагин

- Jul 26, 2021

Феномен лидерство относится к влияние человека (лидер) над остальными членами группы. Согласно словарю American Heritage Dictionary, лидерство — это «знания, отношения и поведение, используемые для влияния на людей для достижения их желаемой миссии».

Если вы прочитаете следующую статью Psychology-online, вы сможете определить характеристики лидера, узнать стили лидерства по Дэниелу Гоулману, чтобы знать, кто являются лучшими лидерами, и знать некоторые черты, которые могут способствовать хорошему лидерству.

Начальник может лично воспринимать успех, навязывать свою позицию и мнение и часто внушать страх. Вместо этого лидер делится успехом со своей командой, прислушивается, вызывает энтузиазм и вдохновляет на улучшение. Можно сказать, что у лидера есть рабочая команда, которая является его подписчикив то время как у директора есть подчиненные сотрудники.

Один из самых интересных вкладов в теорию лидерства был разработан известным американским психологом и профессором Гарварда Дэниелом Гоулманом. Ниже представлены 6 типов лидерства по Гоулману:

1. Принудительное лидерство

«Делай, что я говорю»

Лидер заказать и отправить. Стремится к немедленному выполнению поставленных задач с помощью точных инструкций. Никто не может задавать ему вопросы, и он не спрашивает мнения. Его рекомендуется использовать только тогда, когда это необходимо, поскольку в долгосрочной перспективе этот стиль нарушает рабочую среду и отрицательно влияет на достижение целей компании, так как работники демотивированы, не сотрудничают, перестают передавать идеи из страха быть отвергнутыми, и т.п.

Он хорошо работает в кризисных ситуациях, когда решающим фактором является немедленная реакция, или с проблемными работниками, у которых все остальное уже не удалось.

2. Ориентационный стиль

«Иди со мной»

Наставник-лидер — это провидец; У него четкое долгосрочное видение, и с его энтузиазмом он мобилизует людей на это видение. Руководящее руководство порождает большую приверженность целям и стратегии организации. Этот стиль улучшает рабочую среду. Правила успеха ставятся на стол одинаково для всех, что дает им свободу экспериментировать и вводить новшества.

Обычно это хорошо работает в большинстве ситуаций, хотя и терпит неудачу, если команда состоит из экспертов, которые более опытны, чем лидер. Создает большую мотивацию.

3. Партнерский стиль

«Люди на первом месте»

Этот стиль руководства вращается вокруг людей. Он стремится к тому, чтобы отношения между людьми были гармоничными. Ваши эмоции выше задач и целей. Сотрудники могут выполнять свою работу так, как они считают нужным.

Это подходящий тип лидерства, если вы хотите построить гармонию в команде, улучшить коммуникацию, когда команда новая или когда вам нужно мотивировать их во время стрессовых ситуаций. Напротив, может создаться впечатление, что низкая производительность допустима. Его следует сочетать с другими стилями, например стилем ориентации.

4. Демократический стиль

“Что вы думаете?»

У рабочих есть право голоса и право голоса при принятии решений, тем самым увеличивая гибкость и обязанность. Лидер, основанный на широком участии, всегда стремится к принятию решений на основе консенсуса, люди, которые находятся в демократической системе, как правило, очень реалистично относятся к тому, чего можно или нельзя достичь.

Восток тип делового лидерства он работает очень хорошо, когда лидер не уверен в правильном направлении движения или когда ему нужно генерировать свежие идеи для достижения целей. Этот стиль теряет свое значение, когда сотрудники не обучены или не имеют достаточной информации, чтобы высказать свое мнение.

5. Образцовый стиль

«Делай то, что я ожидаю, не говоря тебе”

Имплантаты лидера очень высокие стандарты маркировка производительности очень конкретные рекомендации. Правила работы обычно ясны руководителю, но он не объясняет их четко, вместо этого он ожидает, что люди будут знать, что им нужно делать. Многие сотрудники обременены требованиями к совершенству со стороны лидера, который устанавливает стандарты. Гибкости и ответственности не существует, и работа становится сосредоточенной на задаче и становится рутинной. Если лидер отсутствует, люди чувствуют себя лишенными направления, поскольку они привыкли к тому, что лидер устанавливает правила.

Образцовый стиль следует использовать редко, так как он портит настроение команды. Это может быть полезно, когда у нас есть отличный специалист в этой области, и мы стремимся учиться, подражая их способам работы.

6. Формирующий стиль

«Попробуй …»

Согласно Гоулману, его главная цель этого стиля лидерства — развитие талантов людей. Они помогают сотрудникам определить свои профессиональные сильные и слабые стороны и стремления, помогая ставить цели развития. Эти лидеры ставят перед своими сотрудниками сложные задачи и готовы терпеть краткосрочные неудачи, поскольку в первую очередь сосредоточены на личном развитии. Это мотивирует их проявлять инициативу и создает среду для совместного роста. Такое лидерство хорошо работает, если сотрудники знают о своих слабостях и хотят улучшить свою работу. В этом мало смысла, если по какой-либо причине они сопротивляются обучению или совершенствованию.

Если вы хотите узнать, какой у вас стиль лидерства, мы рекомендуем это сделать. тест на лидерство с результатами.

Вы хотите знать, как быть хорошим лидером? Теперь, когда вы знаете стили лидерства по Гоулману, мы предлагаем вам список качеств, способствующих хорошему лидерству:

- Эмоциональный интеллект: мы определяем Эмоциональный интеллект как чувствительность замечать настроение и общий климат в группе.

- Самоуверенность: не зависеть от одобрения других.

- Примите свои собственные ограничения: знать и уважать свои собственные и чужие ограничения.

- Сдерживать и откладывать действия: отдавать предпочтение размышлениям над импульсами, откладывать решения. Развивайте стратегическое видение.

- Скромность: учиться на критике других.

- Щедрость: применяйте его, особенно когда есть проблемы, не обвиняйте других.

Гоулман утверждает, что лучшие лидеры не используют только один тип лидерства. Эффективность лидера в иметь возможность гибко переключаться с одного стиля на другой в сложившейся ситуации.

На практике каждому из шести стилей отведено свое место. Гоулман подчеркивает, что деловой климат и ситуация находятся в постоянном движении, поэтому лидер должен знать, когда использовать тот или иной тип лидерства для большей эффективности.

Однако можно сказать, что лидеры, освоившие четыре или более стиля, особенно ориентировочный, демократический, аффилиативный и формирующий— иметь лучший деловой климат и лучшие результаты. Они способствуют развитию профессиональных навыков и приверженности делу. С другой стороны, мы должны помнить, что мы можем быть приятными и преданными, но если мы не достигнем целей, мы не будем лидерами.

Даже если у нас нет людей на попечении, знание различных стилей лидерства может быть полезно для рабочих групп, групп друзей и даже для ваших личных отношений.

Эта статья носит чисто информативный характер, в Psychology-Online мы не можем поставить диагноз или рекомендовать лечение. Приглашаем вас обратиться к психологу для лечения вашего конкретного случая.

На чтение 4 мин. Просмотров 2.4k. Опубликовано

Известный психолог Дэниел Гоулман считает, что существует шесть различных стилей лидерства, и каждый можно использовать в зависимости от желаемого результата.

В современном обществе мы почти все время проводим с людьми. Вот поэтому лидерство – фундаментальный навык. Многие психологи изучали эту концепцию, и одним из них был Дэниел Гоулман. Гоулман наиболее известен своими работами по эмоциональному интеллекту. Однако, он также пишет о стилях лидерства и исследует их.

Классификация cтилей лидерства Гоулмана часто используется в различных дисциплинах. В бизнесе, например, многие руководители и менеджеры изучают его работу, чтобы улучшить свои лидерские качества. Прочитав эту статью, вы узнаете больше о различных стилях лидерства.

Содержание

- Какие стили лидерства существуют по Дэниелу Гоулману?

- 1 – Авторитетное лидерство

- 2- Лидер-демократ

- 3- Товарищеское лидерство

- 4- Визионер

- 5- Ведущий лидер

- 6- Лидер-коуч

Какие стили лидерства существуют по Дэниелу Гоулману?

В своей книге « Лидерство, которое приносит результаты» Дэниел Гоулман описывает шесть различных типов управления. Каждый тип основан на компоненте эмоционального интеллекта .

По словам Гоулмана, эти шесть стилей лидерства не являются несовместимыми. Напротив, хорошие лидеры могут использовать элементы каждого стиля, чтобы лучше адаптироваться к текущей ситуации.

В любом случае, чтобы выбрать лучший стиль для той ситуации, в которой вы находитесь, вы сначала должны знать, что они собой представляют:

- Авторитетный

- Демократичный

- Аффилиативный

- Визионер

- Ведущий лидер

- Коучинг

1 – Авторитетное лидерство

Этот первый стиль руководства основан на дисциплине. Лидеры, которые следуют этому стилю, превыше всего ставят поддержание порядка. С этой целью они обычно дают короткие, конкретные и точные инструкции. В общем, последствия невыполнения этих инструкций суровы. Такие лидеры пытаются показать пример плохого поведения других людей, чтобы ни у кого не возникло соблазна расслабиться.

Такой стиль руководства обычно не мотивирует команду. Сотрудники чувствуют, что сами не могут контролировать свою работу. У них создается впечатление, что они как машины.

Следовательно, такой стиль руководства нужно применять только в экстремальных ситуациях. Это полезно, если вам нужно предпринять конкретные действия или если у вашей организации или группы много проблем. Например, во время чрезвычайной ситуации или для чрезвычайно сложной задачи, требующей точности.

2- Лидер-демократ

Этот стиль руководства гласит, что при принятии решения очень важно учитывать мнение каждого. Обычно лидеры назначают много встреч, проводят дебаты и дискуссии. Этот стиль особенно полезен в случаях, когда у вас много времени, чтобы выбрать правильный путь.

Демократичное лидерство подойдет, если вы работаете с профессиональной командой, где люди уже знают кому и что выполнять. Вам нужно просто иногда предлагать свою помощь.

3- Товарищеское лидерство

Третий тип лидерства основан на создании связей между членами команды. Таким образом, они могут работать и сотрудничать в гармонии. Руководители, использующие этот стиль, стараются создать хорошую рабочую атмосферу, потому что понимают, как это влияет на их сотрудников.

Основная проблема, с которой сталкиваются такие лидеры- отсутствие дисциплины и организации. У них также могут быть проблемы во время конфликтов, потому что люди будут более эмоционально вовлечены в ситуацию.

4- Визионер

Руководители, использующие этот стиль лидерства, мотивируют своих сотрудников ясными и захватывающими перспективами. Они также помогают каждому увидеть свою роль в проекте. Главное преимущество этого типа лидерства в том, что у каждого есть четкое представление о конечной цели. Это заставляет всех чувствовать себя более мотивированными .

В целом этот стиль руководства – один из самых популярных на сегодняшний день.

5- Ведущий лидер

Роль ведущего лидера заключается в том, чтобы определить курс действий и убедиться, что все его придерживаются. Лицо, задающее ритм, хочет показать всем остальным пример. Как правило, это менеджеры и начальники, которым нравится чувствовать, что они играют ведущую роль в проекте.

Проблема с этим стилем лидерства заключается в том, что он не предполагает какие-то новые действия команды. Нужно просто следовать заданному курсу.

Этот тип лидерства особенно эффективен, когда лидер является экспертом в своей области. В результате остальные члены группы должны рассматривать проект как возможность обучения.

6- Лидер-коуч

Последний тип лидерства основан на помощи членам группы в поиске их сильных и слабых сторон. Лидер помогает каждому человеку полностью раскрыть свой потенциал. Идея этого стиля заключается в том, что такой работник сможет эффективнее работать, чем тот, кто не раскрыл свой потенциал.

У каждого стиля лидерства Дэниела Гоулмана есть свои преимущества и недостатки. Вот почему так важно тщательно проанализировать ситуацию и выбрать наиболее подходящий вариант в зависимости от обстоятельств. Развитие лидерских навыков полезно не только для менеджеров и руководителей, но и для всех, кто должен работать в команде для достижения цели.

Если вы нашли ошибку, пожалуйста, выделите фрагмент текста и нажмите Ctrl+Enter.

В книге Джо Оуэна «Как управлять людьми» раскрываются три составляющие менеджмента: рациональная, эмоциональная, политическая. Другие исследователи тоже отметили, что в мире управления играет роль не только рациональное начало, важно и эмоциональное. Именно эмоциональной составляющей лидерства уделяется внимание в книге «Эмоциональное лидерство. Искусство управления людьми на основе эмоционального интеллекта». Авторами книги выступают признанные эксперты по управлению бизнесом Дэниел Гоулман, Ричард Бояцис и Энни Макки.

Поговорим об эмоциональном лидерстве и шести стилях эмоционального управления «по Гоулману».

Об эмоциональном интеллекте

Любой тренинг лидерства прежде всего объяснит, что основная задача лидера — «зажечь», воодушевить, вызвать готовность к действию. Одни только интеллект или логика с этим вряд ли справятся. Видимо, подключаются «другие силы», пробуждающие определённые чувства и эмоции. Чтобы достигать подобного эффекта лидер владеет неким разумным поведением в эмоциональной области, которое называют эмоциональным интеллектом.

Значительной доле успеха лидер обязан именно эмоциональному интеллекту. Это он помогает лидеру вдохновлять людей на трудовые подвиги, воспитывать преданность. Благодаря грамотно организованному эмоциональному климату подчинённые такого руководителя не поддадутся, если их попытаются переманить, будут демонстрировать полную отдачу и приносить максимальную пользу по сути не своему бизнесу, но не без удовольствия для себя самих.

Высший пилотаж лидерства — затрагивать эмоции. Этому учат лидерские тренинги, а значит эмоциональный интеллект можно в себе развить.

Эмоциональный интеллект — это способность управлять собой и отношениями с другими людьми. Эмоциональным лидерством называют управление, основанное на эмоциональном интеллекте. Гоулман убеждает, что эмоциональный интеллект в управлении намного важнее рационального.

Физиологическое объяснение эмоционального воздействия

Причины эмоционального воздействия лидера на людей лежат в физиологической плоскости и связаны с устройством человеческого мозга. Наши эмоциональные центры контролируются лимбической системой, которая является открытой. Если сравнить её с системой другого типа, например, кровеносной, то кровеносная — закрытая, поэтому регулируется самостоятельно, в то время как открытые системы очень зависят от внешних источников.

То, что происходит в кровеносных системах окружающих нас людей, никак не влияет на наше кровообращение. А вот эмоциональная стабильность человека довольно зависима от того, что его окружает.

Это совершенно понятно с точки зрения физиологии, но является открытием для многих — находящиеся рядом люди способны влиять на нашу лимбическую систему (а это физиология), которая под этим влиянием корректирует наши эмоции.

Чем сплочённее группа, тем свободнее обращаются внутри неё чувства, эмоции, и даже свежая информация. При постоянном взаимодействии лимбических систем членов группы образуется общий эмоциональный фон, в который каждый вносит свои оттенки. Но именно лидер управляет им, создавая необходимый резонанс.

Резонансное лидерство

В свете выше описанного, лидер, который не интересуется чувствами окружающих, создаёт диссонанс, не обеспечивая присутствующих условиями для обмена эмоциями. Это может привести к выходу негатива, подавленности и тяжёлой нагнетённой атмосферы.

Третьего не дано: если лидеру не удаётся создать резонанс, он создаёт диссонанс, посылая коллективу отрицательные сигналы.

Это недопустимо для лидера, поэтому любой тренинг лидерства прежде всего учит чувствовать группу, взаимодействовать с ней, грамотно толковать её эмоции, «читать» чувства каждого участника. Везде, где есть диссонансный лидер, люди плохо работают, устают, страдают, у них потеряно внутреннее равновесие.

Резонансный лидер проникается чувствами коллектива и «подключаясь» к эмоциональному фону, направляет эмоции людей в позитивное русло. При такой ситуации достаточно быть искренним, делиться своими идеями, в которые веришь, и они тут же получат отклик в эмоциях окружающих. Получить соответствующие навыки можно на тренинге по эмоциональному интеллекту.

Но не все лидеры такие.

Если лидеры, которых условно называют «несведущими». Они пытаются вызвать положительный резонанс, не учитывая ситуацию. Возможно подчинённым плохо, может они находятся в негативном эмоциональном фоне, но «несведущий» не заметит этого. В каком случае подобное возможно? Такое встречается, если лидер эгоцентричен, соответственно не умеет чувствовать окружающих.

Ещё один тип лидеров — демагоги, под воздействие которых нежелательно попадаться. С одной стороны, они умеют вести за собой и влиять на массы. С другой — они ведут не «к светлому», а наоборот, к негативу и разрушению. Для влияния эти лидеры используют деструктивные эмоции, например, страх или гнев.

Управление на основе одного только интеллекта не менее опасно. Интеллект, развитое мышление — качества, которые открывают двери к лидерству. Даже больше: без интеллекта вход в лидерство воспрещён. Но сам по себе интеллект не делает человека лидером.

Свои замыслы лидеры осуществляют не только разумом, но и сердцем. Они мотивируют, направляют, вдохновляют, прислушиваются, убеждают и, что очень важно, находят живой отклик.

Без чувств лидерство невозможно. И, кстати, человек, не способный слышать собственные чувства, не способен услышать других. Без сердца управление будет использованием, манипуляцией, только не лидерством.

Об этом предостерегал Альберт Эйнштейн: «Мы должны постараться не сделать интеллект нашим богом. Он, конечно, обладает мощными мускулами, но лишён личности. Он не может управлять — он может только служить».

Стили эмоционального лидерства

Эмоциональные лидеры воздействуют на эмоции разными способами. Ниже представлены 6 стилей, которые выделил Гоулман в своей книге. Если вы чувствуете себя лидером или иногда проявляете себя как лидер, попробуйте определить свой стиль, возьмите на вооружение рекомендации для каждого стиля лидерства, запомните лучшие приёмы. Понимать себя иногда эффективнее, чем любые лидерские тренинги и семинары.

Лидер-коуч

Он действует под девизом: «Попробуйте это!» Этот лидер отлично мотивирует, вдохновляет на новые достижения. Он умеет проявить эмпатию, доверять, развивать чувство принадлежности к группе.

Иллюстрацией этого типа лидерства может стать легендарный «отец рекламы» Дэвид Огилви. Он помогал каждому члену команды развиваться, практикуя задушевные разговоры с коллегами, которые выходили далеко за рамки должностей и формальностей — о личной жизни, мечтах, планах. Многие сказали бы, что на подобное нет времени, но только не он. Он всегда находил время на общение, в результате — всегда был в курсе настроения команды, которая ему доверяла.

Сила этого стиля лидерства в погружении в жизнь каждого члена своей команды и искреннем соучастии.

Лидер-демократ

Основным вопросом демократического лидера является «И какие у вас мысли?» Его сила — в коммуникациях, в которых учитывается мнение каждого.

Такой стиль лидерства идеален, когда существует много возможных путей и приходится делать выбор. Демократический лидер открыт к самым разным мнениям и умеет с ними работать.

Такому лидеру важно не забывать, что негативная оценка тоже может быть полезной, поэтому вовсе не нужно её избегать или игнорировать.

Самое важное в этом стиле лидерства:

- Командная работа.

- Менеджмент конфликтных ситуаций.

- Влияние.

Примером такого стиля может быть лидерство Дэвида Моргана, который был главой австралийского Westpac Bank. 20 дней в год он отводил на сессию, где собиралось 40 человек, чтобы рассказать, как «реально обстоят дела».

Отеческий лидер

Этот тип характерен девизом: «Человек всегда на первом месте!» У него всегда в приоритете создание позитивного настроя в коллективе. Этот лидер каждого видит индивидуальностью и стремиться сделать его работу максимально уютной. Он может предлагать поддержку даже в семейных и бытовых проблемах, в общем вести себя как заботливый отец.

Его сильная сторона — эмпатия, способность чувствовать других, как бы примеряя на себя их эмоции и состояние. Если нужно — он ставит интересы коллег выше целей проекта или бизнеса.

Важно не сомневаться, что это правильный выбор. Лучшая инвестиция в бизнес — это инвестиция в людей.

Руководящий лидер

Его основной подход: «Делайте, что я сказал». Он даёт ясные указания и требует строгого выполнения, устанавливая индивидуальную ответственность.

Основные черты такого лидерства:

- Влияние.

- Направленность на успехи.

- Инициатива.

При этом руководящий лидер активно использует эмпатию и эмоциональный контроль.

Этот тип лидерства идеально проявляет себя в кризисных ситуациях благодаря высокой степени рациональности в руководстве, устойчивости к стрессу, умению контролировать ситуацию и преодолевать трудности эффективнее других типов лидерства.

Лидер достижений

Девиз этого лидера — «Делайте, как я!» Очень ценный тип руководства. Такой лидер ведёт за собой собственным примером. Он может показать, как нужно делать и передаёт свои умения другим членам команды.

Он умеет вживить уверенность, что всегда есть куда расти, всегда нужно стремиться к более высоким результатам, более крупным целям, постоянно развивая свой успех. Это для него важная задача, ради которой он постоянно расширяет горизонты, осваивает новые виды деятельности, возможности, технологии.

Такого лидера отличает ориентированность не на материальные ценности, прибыль или титулы. Самое важное для него — установить собственные стандарты и стандарты команды, которые нужно достичь.

Лидер визуализации

Этот лидер живёт с девизом: «Идите за мной!» Своей основной задачей он видит определение и визуализацию того, как именно достижение каждого участника проекта сложатся в общую картину, к которой стремится все предприятие.

Лидер создаёт видение, верит в него, внушает веру в других и этим вдохновляет сотрудников на инициативу и движение вперёд. Этот тип особенно эффективен, когда предприятию нужна перезагрузка или оно находится на этапе выработки стратегии.

Лидерская стратегия визуализации не совсем подойдёт в случае, если в команде лидера будут люди, разбирающиеся в деятельности предприятия больше, чем руководитель. В этом случае больше подойдёт демократический лидер.

Основы лидерства

Какой бы стиль лидера ни показался вам вашим собственным, или какой бы вы ни выбрали в качестве образца, основой лидерства всегда будет оставаться уважение и доверие членов команды, что удаётся только руководителю с развитой эмоциональной интеллигентностью. Развивая ее, можно стать настоящим лидером, которого поддерживают и за которым идут. Укрепляйте навыки эмоционального лидерства на тренингах по эмоциональному интеллекту и других тренингах, развивающих необходимые для лидера качества.

Укрепить и развить свои лидерские качества можно с ManGO! Games, выбрав необходимые тренинги по лидерству, заказав полный каталог тренингов или подобрав программу обучения вместе с профессионалами ManGO! Games. И помните: лидерами не рождаются — лидерами становятся!

- Research article

- Open Access

- Published:

- Loni Desanghere1,

- Kent Stobart2 &

- …

- Keith Walker3

BMC Medical Education

volume 17, Article number: 169 (2017)

Cite this article

-

31k Accesses

-

13 Citations

-

3 Altmetric

-

Metrics details

Abstract

Background

With current emphasis on leadership in medicine, this study explores Goleman’s leadership styles of medical education leaders at different hierarchical levels and gain insight into factors that contribute to the appropriateness of practices.

Methods

Forty two leaders (28 first-level with limited formal authority, eight middle-level with wider program responsibility and six senior- level with higher organizational authority) rank ordered their preferred Goleman’s styles and provided comments. Eight additional senior leaders were interviewed in-depth. Differences in ranked styles within groups were determined by Friedman tests and Wilcoxon tests. Based upon style descriptions, confirmatory template analysis was used to identify Goleman’s styles for each interviewed participant. Content analysis was used to identify themes that affected leadership styles.

Results

There were differences in the repertoire and preferred styles at different leadership levels. As a group, first-level leaders preferred democratic, middle-level used coaching while the senior leaders did not have one preferred style and used multiple styles. Women and men preferred democratic and coaching styles respectively. The varied use of styles reflected leadership conceptualizations, leader accountabilities, contextual adaptations, the situation and its evolution, leaders’ awareness of how they themselves were situated, and personal preferences and discomfort with styles. The not uncommon use of pace-setting and commanding styles by senior leaders, who were interviewed, was linked to working with physicians and delivering quickly on outcomes.

Conclusions

Leaders at different levels in medical education draw from a repertoire of styles. Leadership development should incorporate learning of different leadership styles, especially at first- and mid-level positions.

Peer Review reports

Background

The need to develop leadership competencies in physicians stems from the recognition that physician leaders support and drive change in reforming healthcare systems [1,2,3,4]. Leadership development in medicine is now emphasized for practicing physicians [5] as well as during their education [6, 7], and is reflected in competency-based medical education [8,9,10,11,12].

Ultimately, leadership development is aimed at effective leadership behaviors. Since leadership is a process of intentional influence [13,14,15], a leader’s behavior towards others is at the heart of leadership. As defined in the Merriam-Webster dictionary, the word “style” refers to “a way of behaving or doing things” [16]. At its core then, leadership style is the leader’s interactions with others. The success of leaders within organizations is not dependent on what they aim to do, but rather on how they do it. Of the many underlying factors that affect leadership behaviour, such as intentions and motivations, there has been considerable importance attached to emotional intelligence (EI).

EI is “the ability to monitor one’s own and others’ feelings and emotions, to discriminate among them and to use this information to guide one’s thinking and actions” [17] (p188). EI is generally conceptualized as having four overarching domains — self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, and relationship management — embracing eighteen different competencies [18]. EI has been linked to better interpersonal relations [19] and compassionate and empathetic patient care, and better communication and professionalism skills [20]. Despite concerns with the reliability and validity of EI measures [21], EI has been linked to effective leadership in many professional arenas [18, 22,23,24], including in medicine [20, 25, 26], hence a model of leadership styles based upon EI. Additionally, it has been incorporated as a key aspect of learning the leader role in the CanMEDS 2015 tools guide [27].

Goleman’s work on leadership styles incorporates EI [28] and is based on the studies carried out by the Hay Group (as referenced in [29]), which claimed that EI accounts for more than 85% of exceptional performance in top leaders. These leadership styles are understood in terms of the leaders’ underlying EI capabilities and each style’s causal link with outcomes [28]. The most effective leaders act according to one or more of six distinct leadership styles depending on the situation: visionary (syn. Authoritative – outlining the vision and allowing innovations and experimentation), coaching (developing long-term goals based upon peoples’ strengths and weaknesses), affiliative (promoting harmony and personal relationships), democratic (emphasizing teamwork and collaboration), pacesetting (focusing on learning new approaches and performance to meet challenging goals), and commanding (seeking immediate compliance) [18]. Although successful leaders are able to adapt the type of leadership style they use to a specific situation or circumstance [30], many leaders may use one style more often than others, which compromises their effectiveness.

Given EI’s link to interpersonal behaviors and leadership effectiveness, Goleman’s six leadership styles are useful for investigating leadership behaviors in medical education. The purpose of this study was to identify Goleman’s leadership styles used by medical education leaders, to delineate any differences across participant groups (first-, middle- and senior-level leaders; study phase I) and to lend insight into the factors that contribute to the appropriateness of the practices in different leadership roles (study phase II). The findings are likely to have implications for individual practice, leadership development and recruitment of future leaders.

Methods

Participants

The participants were medical education leaders at various levels at the College of Medicine of the University of Saskatchewan and at senior-level nationally in Canada. Based upon Adair’s work [31], participants were grouped into one of three formal hierarchical leadership levels: First-level (with limited formal responsibility e.g., medical student and resident leaders), middle-level (responsibilities for larger cross-discipline programs such as undergraduate curriculum and postgraduate programs e.g., course coordinators, curriculum chairs, program directors), and senior-level (with higher and wider responsibility e.g., Associate Deans and Deans). In phase I of this study, participants were recruited from all hierarchical leadership levels within the College of Medicine. Phase II involved only senior-level leaders (who did not participate in phase I of this study) with either a provincial mandate or leadership positions in national level educational organizations (see Table 1).

Full size table

Full size table

Full size table

Phase I

Recruitment letters were sent to all current and six previous leaders at the College of Medicine. The response rate to participate in the study was 35% for the first level leaders, 27% for the middle level leaders and 33% for the senior level leaders. There were 28 first-level, eight middle-level, and six senior-level participants.

Phase II

Semi-structured interviews of eight additional senior medical education leaders (as defined above) selected through purposive sampling were conducted by researcher AS; ten senior level leaders were contacted and eight agreed to participate (response rate: 80%).

Materials and procedure

Phase I

To explore differences in leadership conceptualizations between groups, participants were first instructed to provide a simple written definition of their perception of leadership. To gather data on differences in the leadership styles, the participants filled out a questionnaire, which asked them to reflect on their experiences as a leader, and rank order Goleman’s leadership styles. The participants ranked Goleman’s six styles from most- to least commonly used by ranking their most preferred leadership style as 1, the next preferred leadership style a 2, and so on. If a leadership style was not used, then either a “x” was put against it or left blank, this was later coded by the researchers for analysis purposes as a 7. A Brief description of each leadership style was provided to participants. Qualitative responses of the leadership definitions were thematically categorized within each group and common themes are reported. Descriptive statistics were used to explore the dominant leadership style within each participant group and between gender; for gender differences for first level leaders, results are based on available demographics (9 participants only). Friedman tests were used to determine if there were differences in ranked leadership styles within each leadership group as well as by gender. For any significant effects (p < 0.05), Wilcoxon signed-rank tests, with Bonferroni corrections applied for multiple comparisons, were used to determine which domains differed in their rankings.

Phase II

The semi-structured interview questions were framed to encourage the participants to recall stories and experiences to explore a deeper understanding of their leadership behaviors and describe their leadership styles. Additional questions that explored their interactions with stakeholders included recall and descriptions of when they led a major change and had to rally people around them (see Additional file 1). The interview questions were pilot tested to establish the trustworthiness and credibility of the questionnaire (n = 2) and based upon the pilot data the questions were revised to generate sharing of unique and extraordinary experiences and encourage imagination (see Additional file 1). The interviews incorporated an “ethic of care” [32] aimed at developing trust and openness between the researcher and the participant(s) by attempting to become “co-equals” conversing about a mutually relevant subject. The data were collected by note taking and tape recording. The interview transcripts and the notes were analyzed by one author (AS) in two ways. First, these were reviewed to identify Goleman’s styles for each participant based upon the descriptions of these styles and the process of confirmatory template analysis [33, 34]. Secondly, transcripts were inductively analyzed through content analysis process of coding to identify common themes that affect leadership styles [35, 36].

Results

Phase I

Definition of leadership

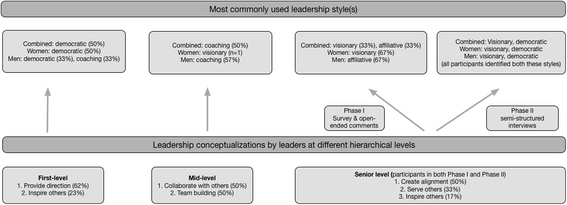

There were two common themes in the conceptualization of leadership by the first-level leaders; these included, 1) providing direction when assisting a group towards a common goal (62%); and 2) inspiring others (23%). For the Mid-level Leaders, two different common themes emerged; leadership entails: (1) collaborative actions with others (50%); and (2) team building (50%). Senior leaders conceptualizations could be summarized in three common leadership themes: (1) alignment (50%); (2) servant leadership (33%); and (3) inspiration (17%).

Rank order of styles and group differences (see Table 2):

The most frequently used leadership style by the first-level leaders (50%) was the democratic style, followed by coaching in both the second (43%) and third ranked (29%) positions. Women within this group identified democratic (50%) as their top ranked style, while men identified both democratic (33%) and coaching (33%) as their top leadership style. Most mid-level leaders (50%) relied on the coaching style as their first and second (38%) ranked styles, followed by affiliative as the third ranking style (38%). This pattern was reflective of the male participants in this group (n = 7) while the single female participant identified visionary followed by coaching and democratic as the top three leadership styles. Senior leaders did not identify one dominant style, but most commonly used visionary (33%) and affiliative (33%) styles, followed by democratic (50%) and coaching (50%) as the second and third ranked styles. Women identified visionary (67%), democratic (67%) and coaching (100%) as the top three styles in decreasing order of frequency, whereas men identified affiliative (67%) as their most frequent style, and coaching (33%), democratic (33%) and pacesetting (33%) as their second most used style. Figure 1 depicts how the leaders at different levels conceptualized leadership and their most commonly used leadership styles.

Leadership styles related to leadership conceptualizations (Phase I)

Full size image

Within each leader group, Friedman tests revealed significant differences in the ranked leadership styles most commonly used for first-[χ2(5) =71.338, p < 0.001], middle- [χ2(5) =23.139, p < 0.001], and senior- [χ2(5) =15.788, p = 0.007] level leaders; as well as across gender [female = χ2(5) =34.311, p < 0.001; male = χ2(5) =34.92, p < 0.001]. Table 3a displays the rank orders for the different leadership styles within each group separately. For the first-level leaders, post hoc comparisons revealed significant differences in the ranked order of the dominant leadership style (democratic) as being ranked significantly higher than affiliative, pacesetting, and commanding styles(ps < 0.05). Middle-level leaders ranked their dominant leadership style (coaching) as significantly more used than pacesetting and commanding styles (ps < 0.05). Among senior-level leaders [χ2(5) =19.00, p = 0.002], post hoc comparisons did not reveal any significant differences between ranked leadership styles except between democratic and commanding styles (p < 0.05). Across all participants, the differences within gender showed that female and male participants ranked their dominant leadership style (democratic and coaching styles respectively) as significantly more used than both pacesetting and commanding styles (ps < 0.05).

Phase II

Semi structured interviews

The following themes were identified. Table 3b displays the leadership styles used by senior-level leaders who were interviewed.

Although most senior leaders prefer democratic and visionary styles, pace-setting and commanding styles are not uncommon: All eight senior leaders described the use of democratic and visionary styles as the most preferred and the most commonly used styles. Most senior leaders used language to reflect democratic style such as, “my leadership style is very much built around generating consensus, bringing people along carefully and I do not tend to be the way out in front or a vocal follow me kind of a leader.” Another leader recalled, “I have used mostly the collaborative style but I have become authoritarian, when I have to.” Most senior leaders found that they had to use the pace-setting style when working with physicians as reflected in the comments, “I am a bit more directive…….most often with physicians,” and “…. who are often difficult to engage and need to be prodded towards organizational goals, but when get motivated produce high-quality results.” The leaders recalled, “to get movement with busy physicians on some issues to be addressed,” e.g., around creating policies, when “it’s really like pulling teeth,” they had to do, “some initial work themselves” and “drop in on the work” themselves to ensure its’ progress. The leaders were cognizant that this may come across as, “autocratic, because you have to get a job done and it’s really hard.”

Even for a specific situation, as the work progresses, styles may need to change to facilitate progress: Most senior leaders were comfortable with, “really good leaders understand the concept of situational leadership… and I have had to adapt my styles…” A common theme was that to achieve results in a timely manner leaders often had to move from visionary, through collaborative to pace-setting /directive styles as reflected in, “my job is to help enable things to happen and get out of the way of bright people who can make it happen,” however, “if you cannot reach consensus, then I change my tactics and if a decision needs to be made, then a majority decision – if that doesn’t work then I make a decision and take responsibility for it.”

Leaders account for the influence of contextual factors and organizational needs: All senior leaders took into account the larger context in which they were operating, as captured in phrases like, “how the college of medicine is situated in and affected by the overarching changes at the university,” “the changes at my institution are affected by the national conversation around educational reform,” and “the work involves fundamental organization-wide deep changes such as a drastic culture change.”

Leaders consider how they themselves are situated in the organization and the situation: One senior leader who had an “easy going” personality and preferred to develop personal relationships found himself in a leadership position where the “culture was very position authority oriented, a little bit formal, a little bit too rules-oriented” limiting the ability to “joke, say something that could be misunderstood.” Another senior leader remarked, “I need to know where I stand with people and how am I perceived?”

Staying authentic to the true nature of “self” makes some styles difficult to practice: According to one senior leader, “I prefer collegial, collaborative, friendly….that’s my preferred modus operandi, …..but when I needed to be autocratic and more directive than I would choose, that is intentional and hard work for me, that is not intuitive.” Another leader mentioned “where I am not doing what comes naturally and I am consuming energy to behave in ways that are not natural or intuitive for me” it creates “stress points,” “as I want to be controlling the outcome but not by overly controlling the people.”

As the leaders mature they become more adept at using multiple styles: Senior leaders were very frank in describing their leadership journey alluding to using a smaller repertoire of styles, more use of autocratic style — “save time, see it my way” early on in their careers to more collaborative and participative styles and expressing divergent opinions in more engaging language such as, “I actually see that differently” compared to earlier phases, “I am right and you are wrong.” However, the journey for some leaders was in the opposite direction, where early on in their careers they were collaborative to the point of being ineffective and had to learn to use “firm” styles such as pace-setting and directive to achieve results.

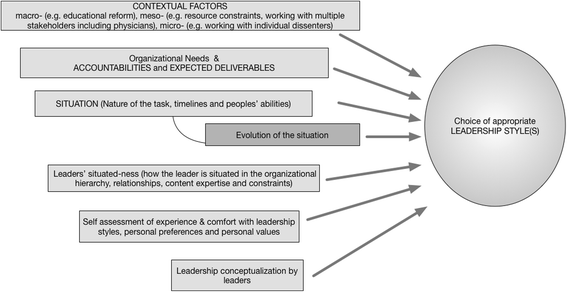

Discussion

Using a mixed methods approach this study on 42 participants identified differences in the repertoire and preferred styles at different levels of medical education leadership. These differences are likely to reflect participants’ conceptualization of leadership, expected accountabilities and deliverables, and adaptation to the situation and latter’s evolution, the larger context, leaders’ awareness of how they are themselves situated, and personal preferences. These are depicted in Fig. 2 and discussed below.

Identified factors affecting the use of leadership styles in medical education (Phase II)

Full size image

The top three most frequently used leadership styles across all leadership levels were democratic, coaching and visionary (authoritative) styles. These three styles are highly positive, and create resonance within the organizations with the potential to boost performance [18]. Our finding that leaders at all three levels were drawing from a large repertoire of styles is consistent with an earlier report that effective leaders are able to utilize a wide range of leadership styles [28]. However, five out of eight senior leaders (semi-structured interviews) did not use coaching or affiliative styles (discussed below).

The preferred use of the democratic style by the first-level leaders could be reflective of their main leadership conceptualization and the interactions with their peer group over whom they have limited, if any, positional authority; the democratic style provides the best opportunity for collaboration with the stakeholders feeling “being heard.” Middle -level leaders are responsible for larger cross-discipline programs and their top ranked leadership style, coaching, also fits in with this level of responsibility as well as their perception that leadership is about working with and developing others; the coaching style typically connects the goals of the followers with the organization’s goals [37] and is a good engagement strategy to promote wider ownership. The senior-level leaders frequent use of visionary and affiliative (Phase I) and visionary and democratic (Phase II) styles as their top ranked styles could indicate a) a broader conceptualization of leadership and a more robust internalization of EI, b) the necessity to engage a wider group of stakeholders over whom they have some positional authority, b) the broad spectrum of accountabilities of senior level positions, and c) their experience and maturity in leadership roles and comfort with the artful practice of leadership.

These findings highlight differences in leadership styles at different levels within the organizational hierarchy where different leadership roles fundamentally serve different purposes (e.g., team leaders with managerial accountabilities vs. strategic leaders involved in policy creation). This idea has some support in the literature; differences in leadership styles were shown between first-, middle-, and senior- leaders in diverse UK organizations, with participative (similar to democratic) and delegative (similar to visionary) leadership styles used increasingly more often with increases in leadership levels [38]. Indeed, a wider range of leadership behaviours in upper leadership positions has been shown to be associated with leader effectiveness in various industries including construction [39] and marketing [40] and other business sectors [41]. However, other factors, such as age and number of years in leadership roles, could have also contributed to differences in the use of specific leadership styles. Previous research has highlighted subtle differences in the use of leadership styles of managers and leaders in various UK organizations [42], with older managers favoring more participative styles than younger managers.

Although, generalizations are fraught with risk, and a deeper analysis of gender differences was not the aim of this study, the overlap in the use of leadership styles by men and women, especially among the first level leaders, may be linked to similar professional identities and leadership conceptualizations. Overall, the democratic style was most frequently used by women leaders whereas their male counterparts placed more emphasis on a coaching style. These findings are somewhat consistent with earlier reports, which showed that women generally make use of more democratic/participative leadership styles whereas men utilize more of a directive/autocratic leadership approach [43]. A preference by women leaders for leadership styles associated with greater effectiveness [44] has been attributed to women’s use of feelings, greater emotional intensities [45, 46], and attention to social sensitivities prior to taking action [47]. Although there are only minimal differences in the leadership ability of men and women [15], women’s leadership styles have been defined as more people-based [48] and collaborative and relationship oriented [49] and this could be leveraged in leadership development programs.

Many contextual factors, which can be considered at three different levels – macro-, meso- and micro — affected a leader’s use of different styles. The senior leaders (phase II) identified the ongoing educational reform — articulated in multiple reports including FMEC-MD [6], FMEC-PG [7], and health professionals for a new century [50] — as the key national-level contextual factor that affected their interactions with stakeholders. Visionary, democratic and coaching styles helped with this engagement through collaborative leadership efforts to guide their thinking, behavior, and outcomes.

A factor associated with the use of pace-setting styles was working with the physicians, who are often difficult to engage. This challenge is likely reflective of the inherent knowledge work nature of physicians and the attendant need for autonomy [51] and associated intrinsic conflict between professionalism and bureaucracy [52]. A surprising finding of our study is that many senior leaders used the commanding and pace-setting styles more often than was expected. It could be that the study sample reflects a higher proportion of those leaders who took charge at a time that required galvanizing change in their organization, e.g., fixing multiple ongoing accreditation issues, or changes in the identity of the organization as opposed to building upon strengths in an already established institution. These two styles often needed to deliver on challenging organizational outcomes require the apex leaders to hold people to high standards [21]. This is also a likely reason for the non-use of coaching and affiliative styles by five out of eight senior leaders in our study (phase II). The use of pace-setting and commanding styles often required reparative work on relationships after the fact or involved drawing upon the relationship capital accrued earlier. This is consistent with an earlier observation that when used too frequently these styles can create dissention and conflict within an organization [18]. A few senior leaders identified the need for supporting others prior to complex and difficult undertakings, which is consistent with the finding that leaders with a high EI provide socio-emotional support before the pressures linked to tasks come into play [53].

An important insight from our study is the senior leaders’ cognizance of how they themselves are established in the “situation” in terms of their position in the organizational hierarchy, relationships with and perceptions of the people, their own content expertise, and constraints. This highlighted the use of emotional intelligence (e.g., self-awareness, self-regulation, motivation, empathy and social skills [37]) required to adapt their style to the peoples’ preferences, motivations and willingness to engage.

Conclusions

The findings from this study have helped elucidate how medical education leaders use different style(s) at each leadership level and the appropriateness of these styles for different accountabilities – with senior leaders using a broader range of styles. Leadership education could be broadened to include the knowledge and use of different leadership styles, especially at first- and middle- level positions. Since EI can be cultivated and refined through emotional competency training and coaching [28]; it is useful to include it in leadership development initiatives within medical education [26, 54, 55]. For the practice of leadership, the styles (i.e. preferences for interactions with people), although prescribed for different situations, need to be rooted in personal philosophy of leadership, and ones’ values and beliefs to be an authentic leader. Mere practice of superficial behaviors may not be sufficient, and often counterproductive when people sense artificiality and pretense. Our results highlight several factors (Fig. 2) affecting the use of leadership styles, which could be considered when moving nimbly between styles. A flexible repertoire of four or more styles makes a highly effective leader [28], so some styles would need to be deliberately developed through formal leadership development combined with an inner journey rooted in self-discovery.

Limitations of the study and future investigations

The findings of our study should be considered in light of the following limitations: (1) participation was limited mostly to leaders at one institution and specific leaders at the national level thereby affecting affect transferability to other settings, (2) the study did not include analysis of objective data on leadership effectiveness, such as performance reviews of leaders or self-reflection of effectiveness, and (3) small sample sizes within leader levels and limited demographic information in the first-level leader group limit generalizability. Future investigations may explore correlations between leader behaviour, EI measures and leader effectiveness and deeper dimensions of gender differences.

Abbreviations

- EI:

-

Emotional Intelligence

- FMEC MD:

-

The Future of Medical Education in Canada Medical Doctor

- FMEC PG:

-

The Future of Medical Education in Canada Postgraduate

References

-

Cunningham TT. Developing physician leaders in today’s hospitals. Front Health Serv Manag. 1999;15(4):42–4.

Google Scholar

-

Clark JE, Armit K. Leadership competency for doctors: a framework. Leadersh Health Serv. 2010;23(2):115–29.

Article

Google Scholar

-

Gowan I. Encouraging a new kind of leadership. BJHCM. 2011;17(3):108–12.

Google Scholar

-

O’Connell MT, Pascoe JM. Undergraduate medical education for the 21st century: leadership and teamwork. Famy med. 2004;36(Suppl):S51–6.

Google Scholar

-

Mountford J, Webb C: When clinicians lead. The Mckinsey Quarterly 2009(February):1–8.

-

The future of medical education in Canada (FMEC): A collective vision for MD education [https://www.afmc.ca/future-of-medical-education-in-canada/medical-doctor-project/index.php].

-

Future of Medical Education in Canada: A collective vision for postgraduate medical education in Canada [http://www.afmc.ca/future-of-medical-education-in-canada/postgraduate-project/pdf/FMEC_PG_Final-Report_EN.pdf. ].

-

Frank JR, Danoff D. The CanMEDS initiative: implementing an outcomes-based framework of physician competencies. Med Teach. 2007;29(7):642–7.

Article

Google Scholar

-

Batalden P, Leach D, Swing S, Dreyfus H, Dreyfus S. General competencies and accreditation in graduate medical education. Health aff (Project Hope). 2002;21(5):103–11.

Article

Google Scholar

-

Simpson JG, Furnace J, Crosby J, Cumming AD, Evans PA, Friedman ben David M, Harden RM, Lloyd D, McKenzie H, JC ML, et al. the Scottish doctor—learning outcomes for the medical undergraduate in Scotland: a foundation for competent and reflective practitioners. Med Teach. 2002;24(2):136–43.

Article

Google Scholar

-

Frank JR (ed.): The CanMEDS 2005 Physician competency network: better standards. Better Physicians. Better Care. Ottawa: The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada; 2005.

-

CanMEDS 2015: Physician competency framework [http://www.royalcollege.ca/rcsite/canmeds/canmeds-framework-e].

-

Bennis WG. On becoming a leader. Oxford: Perseus; 2003.

Google Scholar

-

Kotter JP. What leaders really do. Harv Bus Rev. 1990;68(3):103–11.

Google Scholar

-

Yukl G. Leadership in organizations. 6th ed. Pearson / Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ; 2006.

Google Scholar

-

Style [http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/styles.]

-

Salovey P, Mayer JD. A first formaltheory of emotional intelligence, and a review of then-esixting literature that might pertain to it. Imagination, Cognition, and Personality. 1990;9:185–211.

Article

Google Scholar

-

Goleman D, Boyatzis R, McKee A: Primal Leadership: Realizing the Power of Emotional Intelligence. Boston, Mass.: Harvard Business School Press; 2002.

-

Schutte NS, Malouff JM, Bobik C, Coston TD, Greeson C, Jedlicka C, et al. Emotional intelligence and interpersonal relations. J Soc Psychol. 2001;141(4):523–36.

Article

Google Scholar

-

Arora S, Ashrafian H, Davis R, Athanasiou T, Darzi A, Sevdalis N. Emotional intelligence in medicine: a systematic review through the context of the ACGME competencies. Med Educ. 2010;44(8):749–64.

Article

Google Scholar

-

Santry C. Resilient NHS managers lack required leadership skills, DH research says. Health Serv J. 2011.

-

Prati LM, Douglas C, Ferris GR, Ammeter AP, Buckley MR. Emotional intelligence, leadership effectiveness, and team outcomes. IJOA. 2003;11(1):21–40.

Google Scholar

-

Palmer B, Walls M, Burgess Z, Stough C. Emotional intelligence and effective leadership. Aust J Psychol. 2001;22(1):5–10.

Google Scholar

-

George JM. Emotions and leadership: the role of emotional intelligence. Hum Relat. 2000;53(8):1027–55.

Article

Google Scholar

-

Hammerly ME, Harmon L, Schwaitzberg SD. Good to great: using 360-degree feedback to improve physician emotional intelligence. J Healthc Manag. 2014;59(5):354–65.

Google Scholar

-

Mintz LJ, Stoller JK. A systematic review of physician leadership and emotional intelligence. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6(1):21–31.

Article

Google Scholar

-

Glover Takahashi S, Abbot C, Oswald A, Frank JR. CanMEDS teaching and assessment tools guide. Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada: Ottawa; 2015.

Google Scholar

-

Goleman D, Boyatzis RE, McKee A: Primal Leadership: Learning to Lead with Emotional Intelligence. Boston, Mass.: Harvard Business School Press; 2004.

-

Goleman D. Leadership that gets results. Harv Bus Rev. 2000;78(2):78–90.

Google Scholar

-

Vroom VH, Jago AG. The role of the situation in leadership. Am Psychol. 2007;62(1):17–24.

Article

Google Scholar

-

Adair J. The concise Adair on leadership. London: Thorgood Publishing Ltd.; 2003.

Google Scholar

-

Fontana A, Frey J: The interview: From structured questions to negotiated text. In: Handbook of Qualitative Research. 2nd edn. Edited by Denizen NK, Lincoln YS. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAge; 2000: 645–672.

-

Guest G, MacQueen KM, Namey EE. Introduction to applied thematic analysis, applied thematic analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2012.

Google Scholar

-

King N: Using templates in the thematic analysis of text. In: Essential Guide to Qualitative Methods in Organisational Research. edn. Edited by Cassell C, Symon G. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2004: 256–270.

-

Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research, 2nd edition edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998.

Google Scholar

-

Gall MD, Gall JP, Borg WR: Educational Research: An Introduction, 8th edn. Boston, MA: Pearson Education Inc. (Allyn and Bacon); 2007.

-

Goleman D. What makes a leader? Harv Bus Rev. 2004;82(1):82–91.

Google Scholar

-

Oshagbemi T, Gill R. Differences in leadership styles and behaviour across hierarchical levels in UK organisations. Leadership Org Dev J. 2003;25(1):93–106.

Article

Google Scholar

-

Yang LR, Huang CF, Wu KS. The association among project manager’s leadership style, teamwork and project success. Int J Proj Manag. 2011;29(3):258–67.

Article

Google Scholar

-

Lindgreen A, Palmer R, Wetzels M, Antioco M. Do different marketing practices require different leadership styles? An exploratory study. J Bus Ind Mark. 2009;24(1–2):14–26.

Google Scholar

-

Mishra GP, Grunewald D, Kulkarni NA. Leadership styles of senior and middle level managers: a study of selected firms in Muscat. Sultanate of Oman IJBM. 2014;9(11):72–9.

Google Scholar

-

Oshagbemi T: Age influences on the leadership styles and behaviour of managers. Employee Relations 2004, .26(1):pp.

-

Eagly AH, Johnson BT. Gender and leadership-style — a Metaanalysis. Psychol Bull. 1990;108(2):233–56.

Article

Google Scholar

-

Eagly AH, Johannesen-Schmidt MC: The leadership styles of women and men. Psychol Bull 2001, .57(4):pp.

-

Harshman RA, Paivio A. Paradoxical sex-differences in self-reported imagery. Can J Psychol. 1987;41(3):287–302.

Article

Google Scholar

-

Stevens JS, Hamann S. Sex differences in brain activation to emotional stimuli: a meta-analysis of neuroimaging studies. Neuropsychologia. 2012;50(7):1578–93.

Article

Google Scholar

-

Patel G, Buiting S. Gender differences in leadership styles and the impact within corporate boards. In Commonwealth Secretariat. 2013;39

-

McKinsey: Women leaders, a competitive edge in and after the crisis. Mckinsey & Company 2009, 3:1–28.

-

Eagly AH, Johannesen-Schmidt MC, van Engen ML. Transformational, transactional, and laissez-faire leadership styles: a meta-analysis comparing women and men. Psychol Bull. 2003;129(4):569–91.

Article

Google Scholar

-

Frenk J, Chen L, Bhutta ZA, Cohen J, Crisp N, Evans T, et al. Health professionals for a new century: transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. Lancet. 2010;376(9756):1923–58.

Article

Google Scholar

-

Alvesson M. Knowledge work and knowledge intensive firms. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2004.

Google Scholar

-

Sheldon A. Managing doctors. Frederick. MA: Beard Books; 2002.

Google Scholar

-

Li ZD, Gupta B, Loon M, Casimir G. Combinative aspects of leadership style and emotional intelligence. Leadership Org Dev J. 2016;37(1):107–25.

Article

Google Scholar

-

Johnson JM, Stern TA. Teaching residents about emotional intelligence and its impact on leadership. Acad Psychiatry. 2014;38(4):510–3.

Article

Google Scholar

-

Nowacki AS, Barss C, Spencer SM, Christensen T, Fralicx R, Stoller JK. Emotional intelligence and physician leadership potential: a longitudinal study supporting a link. JHAE. 2016:23–41.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank all of the undergraduate medical students, residents and physician leaders for participating in this study.

Funding

No funding was received for this study.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

-

St. Andrews College, College of Medicine, University of Saskatchewan, Rm 412, 1121 College Drive, Saskatoon, SK, S7N 0W3, Canada

Anurag Saxena & Loni Desanghere

-

College of Medicine, University of Saskatchewan, 5D40 Health Sciences Building Box 19, 107 Wiggins Road, Saskatoon, SK, S7N 5E5, Canada

Kent Stobart

-

College of Education, University of Saskatchewan, Room 3079 28 Campus Drive, Saskatoon, SK, S7N 0X1, Canada

Keith Walker

Authors

- Anurag Saxena

You can also search for this author in

PubMed Google Scholar - Loni Desanghere

You can also search for this author in

PubMed Google Scholar - Kent Stobart

You can also search for this author in

PubMed Google Scholar - Keith Walker

You can also search for this author in

PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Authors AS, KS and KW all made substantial contributions to conception and design of the project. Authors AS and LD contributed to data acquisition, analysis and interpretation of results. All authors were involved in drafting and revising the manuscript and have given final approval and have agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to

Anurag Saxena.

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This research was approved by the Behavioural Research Ethics Board at the University of Saskatchewan (Beh#08–235). All participants provided signed, informed, written consent.

Consent for publication

N/A

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Semi-structured interviews. Interview guide to semi-structured interviews. (DOCX 93 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Saxena, A., Desanghere, L., Stobart, K. et al. Goleman’s Leadership styles at different hierarchical levels in medical education.

BMC Med Educ 17, 169 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-017-0995-z

Download citation

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-017-0995-z

Keywords

- Leadership

- Medical education

- Leadership styles

- Emotional intelligence