| Wagner Group | ||

|---|---|---|

| Группа Вагнера, ЧВК «Вагнер» | ||

Logo of the Wagner Group since April 2023[1] |

||

| Also known as | Wagnerites,[2] Wagners,[3] Musicians,[4] Orchestra[3] | |

| Founders | Yevgeny Prigozhin Dmitry Utkin |

|

| Leader | Vacant | |

| Military leader | Vacant | |

| Ruling body | Council of Commanders[5][6] | |

| Notable leaders |

|

|

| Dates of operation | 2014–present[9] | |

| Headquarters | PMC Wagner Center, Saint Petersburg, Russia | |

| Slogan | «Blood, Honor, Justice, Homeland, Courage» (Russian: Кровь, Честь, Справедливость, Родина, Отвага)[1] | |

| Size |

|

|

| Allies | ||

|

||

| Opponents | ||

|

||

| Battles and wars | ||

|

||

| Designated as a terrorist group by |

|

|

| Alternative logos |   |

|

| Website | wagnercentr |

The Wagner Group (Russian: Группа Вагнера, tr. Gruppa Vagnera), officially PMC Wagner[7] (Russian: ЧВК «Вагнер», tr. ChVK «Vagner»[59]), is a Russian state-funded[60] private military company (PMC) controlled until 2023 by Yevgeny Prigozhin, a former close ally of Russia’s president Vladimir Putin.[7][61] The Wagner Group has used infrastructure of the Russian Armed Forces.[62] Evidence suggests that Wagner has been used as a proxy by the Russian government, allowing it to have plausible deniability for military operations abroad, and hiding the true casualties of Russia’s foreign interventions.[62][63]

The group emerged during the Donbas War in Ukraine, where it helped pro-Russian forces from 2014 to 2015.[7] Wagner played a significant role in the subsequent full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine,[64] for which it recruited Russian prison inmates for frontline combat.[65][66] By the end of 2022, its strength in Ukraine had grown from 1,000 to between 20,000 and 50,000.[67][68][69] It was reportedly Russia’s main assault force in the Battle of Bakhmut. Wagner has also supported regimes friendly with Putin’s Russia, including in the civil wars in Syria, Libya, the Central African Republic, and Mali.[7] In Africa, it has offered regimes security in exchange for the transfer of diamond and gold mining contracts to Russian companies.[70]

Wagner operatives have been accused of war crimes including murder, torture, rape and robbery of civilians,[7][71][72][73] as well as torturing and killing accused deserters.[74][75]

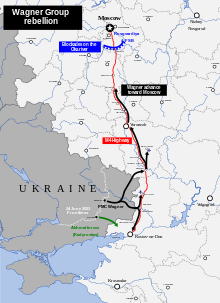

Prigozhin admitted being the leader of Wagner in September 2022.[76][77] He began openly criticizing the Russian Defense Ministry for mishandling the war against Ukraine, eventually saying their reasons for the invasion were lies.[78] On 23 June 2023, he led the Wagner Group in an armed rebellion after accusing the Defense Ministry of shelling Wagner soldiers. Wagner units seized the Russian city of Rostov-on-Don, while a Wagner convoy headed towards Moscow. The mutiny was halted the next day when an agreement was reached: Wagner mutineers would not be prosecuted if they chose to either sign contracts with the Defense Ministry or withdraw to Belarus.[79]

On 23 August 2023, Prigozhin and Wagner commander Dmitry Utkin died in a plane crash in Russia, leaving Wagner’s leadership structure unclear.[80] Western intelligence reported that it was likely caused by an explosion on board, and it is widely suspected that the Russian state was involved.[81]

Origins and leadership

The Wagner Group first appeared in 2014, during the Russian annexation of Crimea.[82] Until 2022 it was unclear who founded and led the group. Both Dmitry Utkin and Yevgeny Prigozhin have been named as its founders and leaders. During the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Prigozhin claimed to have founded Wagner and he was referred to as the group’s head.[76] Some sources say Prigozhin was its owner and financier while Utkin was its military commander.[83]

Yevgeny Prigozhin

It was long reported that Prigozhin had links with Wagner[84][85] and Utkin personally.[86][87] He was sometimes called «Putin’s chef», because of his catering businesses that hosted dinners for Vladimir Putin.[88][89][90] The businessman was said to be the main funder[91][92] and actual owner of the Wagner Group.[93][94] Prigozhin denied any link with Wagner[95] and had sued Bellingcat, Meduza, and Echo of Moscow for reporting his links to the mercenary group.[77] In September 2022, he claimed to have founded the group, saying «I cleaned the old weapons myself, sorted out the bulletproof vests myself and found specialists who could help me with this. From that moment, on May 1, 2014, a group of patriots was born, which later came to be called the Wagner Battalion».[76] Prigozhin became Wagner’s public face and was referred to as its chief, but as he had no military background, he reportedly relied on Utkin to command Wagner’s military operations.[83]

Dmitry Utkin

Utkin was a Russian military veteran. Before his involvement with the Wagner Group, he was a lieutenant colonel and brigade commander of a Spetsnaz GRU unit,[96][9][97][98] and fought in the First and Second Chechen wars. Many sources name Utkin as a founder and the first commander of Wagner.[83][99] Reportedly, Utkin was an admirer of Nazi Germany and the group was named from his alias «Wagner».[100] The European Union sanctions against the Wagner Group name Utkin as its founder and leader.[83] It is reported that Utkin was Wagner’s military commander, responsible for overseeing its military operations, while Prigozhin was its owner, financier and public face.[83] According to Bellingcat, evidence suggests Utkin «was more of a field commander» and «was not in the driver’s seat of setting up this private army, but was employed as a convenient and deniable decoy to disguise its state provenance».[100]

In December 2016, Utkin was photographed with Russian president Putin at a Kremlin reception in honour of those who had been awarded the Order of Courage and the title Hero of the Russian Federation, along with Alexander Kuznetsov, Andrey Bogatov [ru] and Andrei Troshev.[101] Kuznetsov (alias «Ratibor») was said to be the commander of Wagner’s first reconnaissance and assault company, Bogatov was the commander of the fourth reconnaissance and assault company, and Troshev served as the company’s «executive director».[102] A few days after, Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov confirmed the presence of Utkin at the reception.[103][104]

Konstantin Pikalov

Colonel Konstantin Aleksandrovich Pikalov (alias «Mazay») was said to have been put in charge of Wagner’s African operations in 2019.[100] Pikalov served as an officer in Russia’s experimental military unit numbered 99795, based in the village of Storozhevo, near Saint Petersburg. The unit was tasked, in part, with «determining the effects of radioactive rays on living organisms». Following his retirement, he continued to live on the military base until at least 2012 and ran a private detective agency. In 2014 he allegedly took part in suppressing opponents of the Russian-backed president of Republika Srpska, Milorad Dodik, during the Republika Srpska general election. Between 2014 and 2017, Pikalov traveled several times to destinations near the Ukrainian border, sometimes on joint bookings with known Wagner officers.[100] Former employees of Prigozhin said Pikalov took part in military operations in Ukraine and Syria.[100]

Organization

In early 2016, Wagner had 1,000 employees,[13] which later rose to 5,000 by August 2017,[105] and 6,000 by December 2017.[12] The organization was said to be registered in Argentina[13][105] and has offices in Saint Petersburg[106] and Hong Kong.[107] In November 2022, Wagner opened a new headquarters and technology center at the PMC Wagner Center building in the east of Saint Petersburg.[108]

In early October 2017, the SBU said that Wagner’s funding in 2017 had been increased by 185 million rubles ($3.1 million) and that around forty Ukrainian nationals were working for Wagner, with the remaining 95 percent of the personnel being Russian citizens.[109] One Ukrainian was killed in Syria while fighting in the ranks of Wagner in March 2016,[110] and three were reported overall to have died that spring.[111] Armenians, Kazakhs and Moldovans have also worked for Wagner.[112]

Following the deployment of its contractors between 2017 and 2019, to Sudan,[31] the Central African Republic,[32] Madagascar,[113] Libya[39] and Mozambique,[43] the Wagner Group had offices in 20 African countries, including Eswatini, Lesotho and Botswana, by the end of 2019.[114] Early in 2020, Erik Prince, founder of the Blackwater private military company, sought to provide military services to the Wagner Group in its operations in Libya and Mozambique, according to The Intercept.[115] By March 2021, Wagner PMCs were reportedly also deployed in Zimbabwe, Angola, Guinea, Guinea Bissau, and possibly the Democratic Republic of Congo.[116]

According to the Financial Times, the Wagner Group does not exist as a single incorporated entity, but instead as a «sprawling network of interacting companies with varying degrees of proximity to [Prigozhin’s] Concord group» – such as Concord Management and Consulting and Concord Catering. This abstruse structure has allegedly complicated efforts by western governments to restrict Wagner’s activities.[117]

Based partly on leaked documents provided by the Dossier Center, investigative journalist David Patrikarakos has stated that Wagner has never been under the control of either the GRU or the Ministry of Defense, as has often been claimed, but is instead exclusively run by Prigozhin.[118]

Recruitment, training, techniques

The company trains its personnel at a Russian MoD facility, Molkino (Молькино),[97][119] near the remote village of Molkin, Krasnodar Krai.[120][121][122] The barracks at the base are officially not linked to the Russian MoD, with court documents describing them as a children’s vacation camp.[123] According to a report published by Russian monthly Sovershenno Sekretno [ru], the organisation that hired personnel for Wagner did not have a permanent name and had a legal address near the military settlement Pavshino in Krasnogorsk, near Moscow.[124] In December 2021, New Lines magazine analyzed data about 4,184 Wagner members who had been identified by researchers at the Ukrainian Center of Analytics and Security, finding that the average age of a Wagner private military contractor (PMC) is forty years old and that the PMCs came from as many as fifteen different countries, though the majority were from Russia.[125]

When new PMC recruits arrive at the training camp, they are no longer allowed to use social network services and other Internet resources. Company employees are not allowed to post photos, texts, audio and video recordings or any other information on the Internet that was obtained during their training. They are not allowed to tell anyone their location, whether they are in Russia or another country. Mobile phones, tablets and other means of communication are left with the company and issued at a certain time with the permission of their commander.[126]

Passports and other documents are surrendered and in return company employees receive a nameless dog tag with a personal number. The company only accepts new recruits if a 10-year confidentiality agreement is established and in case of a breach of the confidentiality the company reserves the right to terminate the employee’s contract without paying a fee.[126] According to the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU), Russian military officers are assigned the role of drill instructors for the recruits.[127][128] During their training, the PMCs receive $1,100 per month.[129]

The pay of Wagner PMCs, who are usually retired regular Russian servicemen aged between 35 and 55,[129] is estimated to be between 80,000 and 250,000 Russian rubles a month (667–2,083 USD).[130] One source stated the pay was as high as 300,000 (US$2,500).[101]

In late 2019, a so-called Wagner code of honor was revealed that lists ten commandments for Wagner’s PMCs to follow. These include, among others, to protect the interests of Russia always and everywhere, to value the honor of a Russian soldier, to fight not for money, but from the principle of winning always and everywhere.[131][132]

With increasing casualties on both sides in the war in Ukraine, the Russian government used the Wagner Group for recruitment. The NGO Meduza reported that the Russian Defense Ministry had taken control of Wagner’s networks and was using its reputation for recruitment, but that the requirements had been reduced, with drug tests also reportedly not being done before duty.[133] According to British intelligence, since July 2022 at the latest, the Wagner Group has been trying to recruit inmates from Russian prisons in order to alleviate the lack of cadets. In return for agreeing to fight in Ukraine, the criminals are promised a shortening of the sentence and monetary remuneration.[134] BBC Russian Service reported that according to jurists, it is not legal to send inmates to war.[135] Captured and retired members report that the Wagner policy of «zeroing out» (summary execution) of fighters who retreat or desert means that in situations where regular Army units would retreat, Wagner continues its assault. «If they move forward, they at least have the chance to live another day. If they go back, they’re dead for sure.» A Ukrainian battalion commander reported that in intercepted radio traffic on the battlefield, Ukrainians hear «over and over» Wagner commanders giving the order: «Anyone who takes a step back, zero them out.»[136]

The Wagner Group reportedly recruited imprisoned UPC rebels in the Central African Republic to fight in Mali and Ukraine. They are reportedly nicknamed the «Black Russians».[137]

Units

Rusich unit

The Wagner Group includes a contingent known as Rusich, or Task Force Rusich,[138] referred to as a «sabotage and assault reconnaissance group», which has been fighting as part of the Russian separatist forces in eastern Ukraine.[139] Rusich are described as a far-right extremist[140][141] or neo-Nazi unit,[142] and their logo features a Slavic swastika.[143] The group was founded by Alexey Milchakov and Yan Petrovsky in the summer of 2014, after graduating from a paramilitary training program run by the Russian Imperial Legion, the fighting arm of the Russian Imperial Movement.[144] As of 2017, the Ukrainian Prosecutor General and the International Criminal Court (ICC) were investigating fighters of this unit for alleged war crimes committed in Ukraine.[145]

Serb unit

Wagner is believed to have a Serb unit, which was, until at least April 2016, under the command of Davor Savičić, a Bosnian Serb[19] who was a member of the Serb Volunteer Guard (also known as Arkan’s Tigers) during the Bosnian War and the Special Operations Unit (JSO) during the Kosovo War.[146][147] His call sign in Bosnia was «Elvis».[147] Savičić was reportedly only three days in the Luhansk region when a BTR armored personnel carrier fired at his checkpoint, leaving him shell-shocked. After this, he left to be treated.[19] He was also reported to had been involved in the first offensive to capture Palmyra from the Islamic State (ISIL) in early 2016.[146]

One member of the Serbian unit was killed in Syria in June 2017,[148] while the SBU issued arrest warrants in December 2017, for six Serbian PMCs that belonged to Wagner and fought in Ukraine, including Savičić.[149] In early February 2018, the SBU reported that one Serb member of Wagner, who was a veteran of the conflict in Syria, had been killed while fighting in eastern Ukraine.[150][151] In January 2023, Serbian president Aleksandar Vučić criticized Wagner for recruiting Serbian nationals and called on Russia to put an end to the practice, noting that it is illegal under Serbian law for Serbian citizens to take part in foreign armed conflicts.[152]

Relationship with the Russian state

On 27 June 2023 President Putin, while declaring an investigation into Wagner Group spending, confirmed that the Russian state fully funded it from the country’s defense budget and state budget. From May 2022 to May 2023 alone, the Russian state paid 86.262 billion RUB to the group, approximately $1 billion.[153] Putin in the past frequently denied any links between Russian state and «Wagner» and insisted it’s a «private military company».[154][155]

Before that, many Russian and Western observers[who?] believed that the organization does not actually exist as a private military company but is in reality a disguised branch of the Russian MoD that ultimately reports to the Russian government.[156][157][158][159] The company shares bases with the Russian military,[160] is transported by Russian military aircraft,[161][162][163] and uses Russia’s military health care services.[164][165][62] The Russian state is also documented supporting the Wagner Group with passports.[62][166]

The legal status of private military companies in Russia is vague: on one hand, Russian legislation explicitly prohibits «illegal armed formations and mercenary groups», but at the same time the Russian state does not prosecute numerous PMCs employing Russians and operating in Russia, including but not limited to Wagner. Viktor Ozerov once hinted that this ban does not apply for companies «registered abroad» and in such case «Russia is not legally responsible for anything». This vagueness was interpreted as a tool that enables the Russian state to selectively allow operations of PMCs it needs, while preventing creation of any PMCs that would create a risk for Putin and at the same time manage plausible deniability for their actions.[167][168]

As result, a number of PMCs appear to have been operating in Russia, and in April 2012 Vladimir Putin, speaking in the State Duma as Russian prime minister, endorsed the idea of setting up PMCs in Russia.[169][170] Several military analysts described Wagner as a «pseudo-private» military company that offers the Russian military establishment certain advantages such as ensuring plausible deniability, public secrecy about Russia’s military operations abroad, as well as about the number of losses.[171][169][172] Thus, Wagner contractors have been described as «ghost soldiers», due to the Russian government not officially acknowledging them.[173]

In March 2017, Radio Liberty characterized the PMC Wagner as a «semi-legal militant formation that exists under the wing and on the funds of the Ministry of Defence».[174] In September 2017, the chief of Ukraine’s Security Service (SBU) Vasyl Hrytsak said that, in their opinion, Wagner was in essence «a private army of Putin» and that the SBU were «working on identifying these people, members of Wagner PMC, to make this information public so that our partners in Europe knew them personally».[175][176] The Wagner Group has also been compared with Academi, the American security firm formerly known as Blackwater.[177]

According to the SBU, Wagner employees were issued international passports in bulk by the GRU via Central Migration Office Unit 770–001 in the second half of 2018, allegations partially verified by Bellingcat.[178][179]

In an interview in December 2018, Russian president Putin said, in regard to Wagner PMC’s operating in Ukraine, Syria and elsewhere, that «everyone should remain within the legal framework» and that if the Wagner group was violating the law, the Russian Prosecutor General’s Office «should provide a legal assessment». But, according to Putin, if they did not violate Russian law, they had the right to work and promote their business interests abroad. Putin also denied allegations that Prigozhin had been directing Wagner’s activities.[180]

In September 2022 Prigozhin officially admitted to founding and managing «Wagner Group» which started as a battalion participating from May 2014 on the Russian side in the War in Donbas.[181]

According to a Russia investigative media Russkiy Kriminal, the military command of «Wagner» is held directly by the GRU, including its current head Igor Kostyukov and former head of Russian SSO Aleksey Dyumin, with Prigozhin being responsible for its business administration. «Wagner» is mostly populated by current and former GRU operatives, and used for operations where direct GRU participation is undesirable.[182] Russian journalists also link Prigozhin to Yuri Kovalchuk and Sergey Kiryenko, both influential figures close to Putin.[183] «Wagner’s» interests in the official structures of Russian Ministry of Defense are reportedly represented by general Sergey Surovikin.[184]

Private military companies are still illegal in Russia, but with their heavy participation in the war in Ukraine they have been legitimized by being referred by the Ministry of Defense and Russian government with the umbrella term of «volunteer detachments».[185]

On 5 May 2023, Prigozhin blamed Russian defense minister Sergei Shoigu and Chief of Staff of the Russian Armed Forces Gen. Valery Gerasimov for «tens of thousands» of Wagner casualties, saying «They came here as volunteers and are dying so you can sit like fat cats in your luxury offices.»[186]

In 2023, the Russian government granted the status of combat veterans to Wagner contractors who took part in Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.[187]

In a video released on 23 June 2023, Prigozhin said that Russian government justifications for the Russian invasion of Ukraine were based on lies.[188] He accused the Russian Defense Ministry under Shoigu of «trying to deceive society and the president and tell us how there was crazy aggression from Ukraine and that they were planning to attack us with the whole of NATO.»[189]

Wagner Group rebellion

On 24 June 2023, Prigozhin was accused by the Russian government of organizing an armed uprising after he threatened to attack Russian forces in response to a claimed air strike on his paramilitary soldiers. Russian security forces accused the founder of the Wagner group of launching a coup attempt as he pledged a «march of justice» against the Russian army. Prigozhin posted a voice memo claiming that Wagner had left Ukraine and was advancing on the Russian city of Rostov-on-Don. Senior Russian generals urged Wagner’s fighters to withdraw. Meanwhile Russia’s national security service, FSB, said it had filed criminal charges against Prigozhin and moved to arrest him.[190] Prigozhin claimed that Wagner mercenary forces entered Rostov without any resistance.[191][192][193][194]

Russian president Putin had stated on 8 February 2022 that the Russian state is not involved and has nothing to do with Wagner’s activities in Africa.[195] On 27 June 2023, he said that Wagner is fully funded by Russia, amounting to $1 billion from the defense ministry and state budget for May 2022 to May 2023 alone.[196] In July, Russian state media said Prigozhin’s Wagner Group had received the equivalent of $9.8B and his Concord catering business $9.6B from state sources.[197] Two weeks later Putin once again stated that «legally Wagner Group does not exist».[198]

On 26 August 2023, following Prigozhin’s death in a plane crash in Tver Oblast, Putin signed a decree ordering Wagner Group fighters to swear an «oath of allegiance» to the Russian state. This new oath applies to all PMCs, including those fighting in Ukraine.[199]

Activities

Russia

Known to operate

Suspected or reported but unconfirmed presence

The Wagner Group is known to have operated in at least 11 countries; Russia, Belarus, Ukraine, Syria, Sudan, Mozambique, Central African Republic, Mali, Libya, Venezuela, and Madagascar, spanning three continents, Europe, Africa and South America. There are unconfirmed reports of activities in other countries.

In August 2023 two Russian citizens were detained in Poland after they were spotted placing «Wagner» stickers and other recruitment materials in public places. According to law enforcement they had over 3000 «Wagner» propaganda items and documented placing over 300 of them in various places in Poland, for which they received 500’000 RUB from Russia.[200]

Ukraine

Wagner has played a significant role in the Russian invasion of Ukraine, where it has been reportedly deployed to assassinate Ukrainian leaders,[64] among other activities, and for which it has recruited prison inmates from Russia for frontline combat.[65][66] In December 2022, United States National Security Council Coordinator for Strategic Communications John Kirby claimed Wagner had 50,000 fighters in Ukraine, including 10,000 contractors and 40,000 convicts.[67] Others put the number of recruited prisoners at more than 20,000,[68] with the overall number of PMC forces present in Ukraine estimated at 20,000.[69] In 2023, Russia granted combat veteran status to Wagner contractors who took part in the invasion.[187]

Crimea annexation and War in Donbas

Wagner PMCs were first active in February 2014 in Crimea[15][16] during Russia’s 2014 annexation of the peninsula where they operated in line with regular Russian army units, disarmed the Ukrainian Army and took control over facilities. The takeover of Crimea was almost bloodless.[201] The PMCs, along with the regular soldiers, were called «polite people» at the time[202] due to their well-mannered behavior. They kept to themselves, carried weapons that were not loaded, and mostly made no effort to interfere with civilian life.[203] Another name for them was «little green men» since they were masked, wearing unmarked green army uniforms and their origin was initially unknown.[204]

After the takeover of Crimea,[201] some 300 PMCs[205] went to the Donbas region of eastern Ukraine where a conflict started between Ukrainian government and pro-Russian forces. With their help, the pro-Russian forces were able to destabilize government security forces in the region, immobilize operations of local government institutions, seize ammunition stores and take control of towns.[201] The PMCs conducted sneak attacks, reconnaissance, intelligence-gathering and accompanied VIPs.[206] The Wagner Group PMCs reportedly took part in the June 2014 Il-76 airplane shoot-down at Luhansk International Airport[17] and the early 2015 Battle of Debaltseve, which involved one of the heaviest artillery bombardments in recent history, as well as reportedly hundreds of regular Russian soldiers.[13]

Following the end of major combat operations, the PMCs were reportedly given the assignment to kill dissident pro-Russian commanders that were acting in a rebellious manner, according to the Russian nationalist Sputnik and Pogrom internet media outlet and the SBU,[172][201] (other sources describe those who started to «turn up dead» and whose fate Wagner was suspected of being responsible for as «the most charismatic and ideologically driven leaders».[136] According to the SBU and the Russian media, Wagner also forced the reorganization and disarmament of Russian Cossack and other formations.[206][207] The LPR accused Ukraine of committing the assassinations,[208][209] while unit members of the commanders believed it was the LPR authorities who were behind the killings.[209][210][211] Wagner left Ukraine and returned to Russia in autumn of 2015, with the start of the Russian military intervention in the Syrian Civil War.[16]

In late November 2017, a power struggle erupted in the separatist Luhansk People’s Republic in Eastern Ukraine between LPR president Igor Plotnitsky and the LPR’s interior minister, Igor Kornet, who Plotnitsky ordered to be dismissed. During the turmoil, armed men in unmarked uniforms took up positions in the center of Luhansk.[212][213] Some of the men belonged to Wagner, according to the Janes company.[214] In the end, Plotnitsky resigned and LPR security minister Leonid Pasechnik was named acting leader «until the next elections.»[215] Plotnitsky reportedly fled to Russia[216] and the LPR’s People’s Council unanimously approved Plotnitsky’s resignation.[217] As of October 2018, a few dozen PMCs remained in the Luhansk region, according to the SBU, to kill any people considered «undesirable by Russia».[218]

2022 invasion of Ukraine

The Times reported that the Wagner Group flew in more than 400 contractors from the Central African Republic in mid- to late-January 2022 on a mission to assassinate Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy and members of his government, and thus to prepare the ground for Russia to take control for the Russian invasion of Ukraine, which started on 24 February 2022.[219] A US official stated that there were «some indications» that Wagner was being employed, but it was not clear where or how much.[220] By 3 March, according to The Times, Zelenskyy had survived three assassination attempts, two of which were allegedly orchestrated by the Wagner Group.[221]

In late March, it was expected that the number of Wagner PMCs in Ukraine would be tripled from around 300 at the beginning of the invasion to at least 1,000, and that they were to be focused on the Donbas region of eastern Ukraine.[222] In late April, a Russian military offensive to take the remainder of the Donbas region dubbed the Battle of Donbas was launched and Wagner PMCs took part in the Battle of Popasna,[47][48] the capture of Svitlodarsk,[223] the Battle of Sievierodonetsk,[49][50] and the Battle of Lysychansk.[51] During fighting near Popasna on 20 May, retired Major General Kanamat Botashev of the Russian Air Force was shot down while flying a Sukhoi Su-25 attack aircraft,[224] reportedly for the Wagner Group.[225]

During the invasion, Wagner PMCs also trained Russian servicemen before they were sent to the frontline.[226]

From the beginning of July,[227] inmates recruited by Wagner, including Prighozin personally, in Russian prisons started participating in the invasion of Ukraine. The inmates were offered 100,000 or 200,000 rubles and amnesty for six months of «voluntary service», or 5 million for their relatives if they died.[228][65] On 5 January 2023, the first group of 24 prisoners[229] recruited by Wagner to fight in Ukraine finished their six-month contracts and were released with full amnesty for their past crimes.[230]

During the Battle of Bakhmut in late September, senior Wagner commander Aleksey Nagin was killed. Nagin previously fought with Wagner in Syria and Libya, and before that took part in the Second Chechen War and the Russo-Georgian War. He was posthumously awarded the title of Hero of the Russian Federation.[231][232] On 22 December, United States National Security Council Coordinator for Strategic Communications John Kirby claimed that around 1,000 Wagner fighters were killed in fighting at Bakhmut during the previous weeks, including some 900 recruited convicts.[233] Ukrainian soldiers and former convicts prisoners of war described the use of recruited convicts at Bakhmut as «bait», as poorly armed and briefly trained convicts were sent in human wave attacks to draw out and expose Ukrainian positions to attack by more experienced units or artillery.[234][235]

Circa 2023, journalist Joshua Yaffa reports that recruited prisoners, make up approximately 80% of Wagner’s manpower. They are identified with the letter «K» and deployed in waves, in intervals of 15–20 minutes, whereas professional mercenaries are given the letter «A» and «held back, entering the battle only once Ukrainian defenses had been softened.»[136] An interviewed former Wagner mercenary who deserted reports a high mortality rate for the prisoners recruited to fight for Wagner in Ukraine: «Once we started using prisoners, it was like a conveyor belt. A group comes—that’s it, they’re dead.» He stopped remembering their names or call signs. «A new person shows up, survives for five minutes, and he’s killed. It was like that day after day.»[136]

In mid-January 2023, the Wagner Group captured the salt mine town of Soledar after heavy fighting. During the battle, Wagner reportedly surrounded Ukrainian troops in the center of the town.[236][237] Hundreds of Russian and Ukrainian troops were killed in the Battle of Soledar.[238] Several days later, Wagner captured Klishchiivka, south of Bakhmut, after which they continued advancing west of the settlement.[239][240][241][242]

A US estimate mid-February 2023, put the number of Wagner PMC casualties in the invasion at about 30,000, of which about 9,000 killed. The US estimated that half of those deaths occurred since the middle of December, with 90 percent of Wagner fighters which had been killed since December being convicts.[243] Concurrently, the UK Ministry of Defence estimated that convicts recruited by Wagner had experienced a casualty rate of up to 50 percent.[244]

On July 19, 2023, Prigozhin announced the Wagner Group would no longer fight in Ukraine.[245]

Belarus

|

|

This section needs to be updated. Please help update this article to reflect recent events or newly available information. (August 2023) |

In July 2020, ahead of the country’s presidential election, Belarusian law enforcement agencies arrested 33 Wagner contractors. The arrests took place after the security agencies received information about over 200 PMCs arriving in the country «to destabilize the situation during the election campaign», according to the state-owned Belarusian Telegraph Agency (BelTA).[246] The Belarusian Security Council accused those arrested of preparing «a terrorist attack».[247] Radio Liberty reported the contractors were possibly on their way to Sudan, citing video footage that showed Sudanese currency and a telephone card depicting Kassala’s Khatmiya Mosque among the belongings of those who had been arrested.[246] Others also believed the contractors were simply using Belarus as a staging post on their way to or from their latest assignment,[247] possibly in Africa, with BBC News pointing out the footage of the Sudanese currency and a Sudanese phone card as well.[248]

Russia confirmed the men were employed by a private security firm, but stated they had stayed in Belarus after missing their connecting flight to Turkey[249] and called for their swift release.[250] The head of the Belarusian investigative group asserted the contractors had no plans to fly further to Turkey and that they were giving «contradictory accounts». The PMCs stated they were on their way to Venezuela, Turkey, Cuba and Syria. Belarusian authorities also said they believed the husband of opposition presidential candidate Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya may have ties to the detained men and launched a criminal case against him.[249] The detained contractors were returned to Russia two weeks later.[251]

During the contractors’ detention, Russian media reported that the Security Service of Ukraine had lured the PMCs to Belarus under the pretext of a contract for the protection of Rosneft facilities in Venezuela. The operation’s plan was to force an emergency landing of the contractor’s plane from Minsk as it flew through Ukrainian airspace and, once grounded, the PMCs would have been arrested.[252] Later, Russian president Putin also stated that the detained men were victims of a joint Ukrainian-United States intelligence operation.[253][254] Although the Ukrainian president’s chief of staff, Andriy Yermak, denied involvement in the detentions,[255] subsequently, a number of Ukrainian journalists, members of parliament, and politicians confirmed the operation.

The operation was supposedly planned for a year as Ukraine identified PMCs who fought in eastern Ukraine and were involved in the July 2014 shoot down of Malaysia Airlines Flight 17. The operation failed after being postponed by the Office of the President of Ukraine, which was reportedly informed of it only in its final stage. Ukrainian reporter Yuri Butusov accused Andriy Yermak of «betrayal» after he reportedly deliberately released information on the operation to Russia.[252] Butusov further reported that the Turkish intelligence agency MİT was also involved in the operation.[256] The failure of the operation led to firings and criminal proceedings among Ukraine’s Security Service personnel, according to a Ukrainian intelligence representative using the pseudonym «Bogdan».[257] Former Ukrainian president Petro Poroshenko also claimed in December 2020 that he sanctioned the operation at the end of 2018.[258]

Syria

The presence of the PMCs in Syria was first reported in late October 2015, almost a month after the start of the Russian military intervention in the country’s civil war, when between three and nine PMCs were killed in a mortar attack in Latakia province.[20][259][260]

Wagner PMCs were involved in both Palmyra offensives in 2016 and 2017, as well as the Syrian Army’s campaign in central Syria in the summer of 2017 and the Battle of Deir ez-Zor in late 2017.[19][22][261][24] They were in the role of frontline advisors, fire and movement coordinators,[172] forward air controllers who provided guidance to close air support,[262] and «shock troops» alongside the Syrian Army.[171]

In early February 2018, the PMCs took part in a battle at the town of Khasham, in eastern Syria, which resulted in heavy casualties among Syrian government forces and the Wagner Group as they were engaged by United States air and artillery strikes, due to which the incident was billed by media as «the first deadly clash between citizens of Russia and the United States since the Cold War».[263][264][136][265] Sources said Wagner group losses were anywhere between 10 and 200.

Subsequently, the Wagner Group took part[29] in the Syrian military’s Rif Dimashq offensive against the rebel-held Eastern Ghouta, east of Damascus.[266][267] The whole Eastern Ghouta region was captured by government forces on 14 April 2018,[268][269] effectively ending the near 7-year rebellion near Damascus.[270]

The PMCs also took part[271] in the Syrian Army’s offensive in northwestern Syria that took place mid-2019.[272] As of late December 2021, Wagner PMCs were still taking part in military operations against ISIL cells in the Syrian desert.[273]

On 15 March 2023, the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights said that 266 Russian PMCs were killed in Syria during the civil war.[274]

Africa

The Wagner Group has been active in several countries in Africa starting in 2017. It has provided security and protection to several African regimes. In return, Russian and Wagner-linked companies have been given privileged access to those countries’ natural resources, such as rights to gold and diamond mines, while the Russian state has been given access to strategic locations such as airbases or ports.[70][275] This has been described as a kind of state capture, whereby Russia gains influence over those states and they become dependent on it.[276]

Wagner Group PMCs arrived in Madagascar to provide security for then-president Hery Rajaonarimampianina in the 2018 Malagasy presidential election. In early August 2019, the Wagner Group received a contract with the government of Mozambique to provide technical and tactical assistance to the Mozambique Defense Armed Forces (FADM). At least 200 PMCs and military equipment arrived in Mozambique to fight an Islamist insurgency in Cabo Delgado Province which started on 5 October 2017.

In a September 2023 New York Times opinion piece, American national security expert, Sean McFate, presented Yevgeny Prigozhin’s operation of the Wagner Group in Africa as a template for mercenary money-making or «a blueprint for wannabe mercenary overlords to follow». The model is to find «conflict markets», a state with instability («political rivalries, post-colonial grievances and short on rule of law») and natural resources.[277] Once Prigozhin’s had

spotted an opening, he would pitch it to Mr. Putin, and, if amenable, Mr. Putin would unofficially sanction Wagner’s operations, sometimes providing them with military equipment and intelligence. … With Mr. Putin’s blessing in place, Mr. Prigozhin would approach the potential client, typically a head of state or group of putschists, and propose a deal. He would coup-proof them using Wagner muscle and create an elite military unit to serve them. He would use another arm of his business empire, a troll factory called the Internet Research Agency, to smear domestic opposition, popularize the client and further exploit grievances against the West. In exchange, he very likely demanded two things. First, the regime had to abandon the West and support Russia’s interests. Second, it had to grant Russia access to natural resources such as oil, natural gas and gold.

[277]

Sudan

The earliest reports of PMC Wagner involvement in Sudan came in 2017.[278] The PMCs were sent to Sudan to support it militarily against South Sudan and protect gold, uranium and diamond mines.[279]

Following Omar al-Bashir’s overthrow in a coup d’état on 11 April 2019, Russia continued to support the Transitional Military Council (TMC) that was established to govern Sudan, as the TMC agreed to uphold Russia’s contracts in Sudan’s defense, mining and energy sectors. This included the PMCs’ training of Sudanese military officers.[280] The Wagner Group’s operations became more elusive following al-Bashir’s overthrow. They continued to mostly work with Sudan’s Rapid Support Forces (RSF).[281] Wagner was said to be linked to the Deputy Chairman of the TMC and commander of the RSF, Gen. Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo.[282]

In April 2020, the Wagner-connected company «Meroe Gold» was reported to be planning to ship personal protective equipment, medicine, and other equipment to Sudan amid the coronavirus pandemic.[283] Three months later, the United States sanctioned the «M Invest» company, as well as its Sudan subsidiary «Meroe Gold» and two individuals key to Wagner operations in Sudan, for the suppression and discrediting of protesters.[284]

Following the 2021 Sudanese coup d’état, Russian support for the military administration set up in Sudan became more open and Russian-Sudanese ties, along with Wagner’s activities, continued to expand even after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, leading to condemnation by the United States, United Kingdom and Norway.[281] The Wagner Group obtained lucrative mining concessions. 16 kilometres (10 mi) from the town of Abidiya, in Sudan’s northeastern gold-rich area, a Russian-operated gold mine was set up that was thought to be an outpost of the Wagner Group. Further to the east, Wagner supported Russia’s attempts to build a naval base on the Red Sea. It used western Sudan’s Darfur region as a staging point for its operations in other neighbouring countries, the Central African Republic, Libya and parts of Chad. Geologists of the Wagner-linked «Meroe Gold» company also visited Darfur to assess its uranium potential.[285]

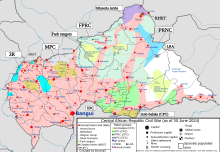

Central African Republic

In 2018, the Wagner Group deployed its personnel to the CAR, to protect lucrative mines, support the CAR government, and provide close protection for the president, Faustin-Archange Touadéra.[286]

By May 2018, it was reported that the number of Wagner PMCs in the CAR was 1,400, while another Russian PMC called Patriot was in charge of protecting VIPs.[287]

By 2021, the situation in the CAR had deteriorated further, with rebels attacking and capturing the fourth-largest city in the country.[288] In response, Russia sent an additional 300 military instructors to the country to train government forces and provide support.[288] The presence of Wagner and other Russian PMCs in the CAR has raised concerns about Russia’s growing influence in Africa and its willingness to flout international law.

In September 2022, The Daily Beast interviewed survivors and witnesses of a massacre committed by the Wagner Group in Bèzèrè village in December 2021, which involved torture, killing and disembowelment of a number of women, including pregnant ones.[289]

According to The New York Times, a report «prepared for members of the U.N. Security Council» found Wagner forces complicit in numerous cases in the Central African Republic of «excessive force, indiscriminate killings, occupation of schools and looting on a large scale, including of humanitarian organizations.»[290][136]

In mid-January 2023, the Wagner Group sustained relatively heavy casualties as a new government military offensive was launched near the CAR border with Cameroon and Chad. Fighting also erupted near the border with Sudan. The rebels claimed between seven and 17 Wagner PMCs were among the dozens of casualties. A CAR military source also confirmed seven Wagner contractors were killed in one ambush.[291]

According to a 2022 joint investigation and report from European Investigative Collaborations (EIC), the French organization All Eyes on Wagner, and the UK-based Dossier Center, Wagner Group has been controlling Diamville diamond trading company in Central African Republic since 2019.[292] According to The New Yorker, the group also holds sway over «much of the timber industry and operates a network of gold and diamond mines», and according to «a senior US intelligence official», the CAR is now a «proxy state» of the Wagner Group. At the same time, a «French military official» complained to journalist Joshua Yaffa, «They don’t really bring stability, or even fight rebel groups all that successfully. What they do is protect the government in power and their own economic interests.»[136]

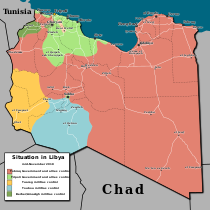

Libya

The group’s presence in Libya was first reported in October 2018, when Russian military bases had been set up in Benghazi and Tobruk in support of Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar, who leads the Libyan National Army (LNA). The group was said to be providing training and support to Haftar’s forces, and Russian missiles and SAM systems were also thought to be set up in Libya.[citation needed] By early March 2019, around 300 Wagner PMCs were in Benghazi supporting Haftar, according to a British government source.[293] The LNA made large advances in the country’s south, capturing a number of towns in quick succession, including the city of Sabha and the El Sharara oil field, Libya’s largest oil field.[294] Following the southern campaign, the LNA launched an offensive against the Government of National Accord (GNA)-held capital of Tripoli, but the offensive stalled within two weeks on the outskirts of the city due to stiff resistance.[295]

By mid-November, the number of Wagner PMCs in Libya had risen to 1,400, according to several Western officials.[296] The US Congress was preparing bipartisan sanctions against the PMCs in Libya, and a US military drone was shot down over Tripoli, with the US claiming it was shot down by Russian air defenses operated by Russian PMCs or the LNA. An estimated 25 Wagner military personnel were killed in a drone strike in September 2020, although the Russian government denied any involvement. The GNA ultimately recaptured Tripoli in June 2020, leading to a ceasefire agreement in October 2020.[297]

Mali

In September 2021 reports surfaced that an agreement was close to being finalized that would allow the Wagner Group to operate in Mali. France, which previously ruled Mali as a colony, was making a diplomatic push to prevent the agreement being enacted. Since late May 2021, Mali has been ruled by a military junta that came into power following a coup d’état.[298] The United Kingdom, European Union and Ivory Coast also warned Mali not to engage in an agreement with the Wagner Group.[299][300][301] Still, on 30 September, Mali received a shipment of four Mil Mi-17 helicopters, as well as arms and ammunition, as part of a contract agreed in December 2020.[302][303]

The following months, Russian military advisors arrived in the country and were active in several parts of Mali.[304][45]

On 5 April 2022, Human Rights Watch published a report accusing Malian soldiers and Russian PMCs of executing around 300 civilians between 27 and 31 March, during a military operation in Moura, in the Mopti region, known as a hotspot of Islamic militants. According to the Malian military, more than 200 militants were killed in the operation, which reportedly involved more than 100 Russians.[46][305]

Venezuela

In late January 2019, Wagner PMCs were reported by Reuters to have arrived in Venezuela during the unfolding presidential crisis. They were sent to provide security for President Nicolás Maduro, who was facing opposition protests as part of the socioeconomic and political crisis that had been gripping Venezuela since 2010. The leader of a local chapter of a paramilitary group of Cossacks with ties to the PMCs reported that about 400 contractors may have been in Venezuela at that point. It was said that the PMCs flew in two chartered aircraft to Havana, Cuba, from where they transferred onto regular commercial flights to Venezuela.[41][306]

An anonymous Russian source close to the Wagner Group stated that another group of PMCs had already arrived in advance of the May 2018 presidential election.[41][306] Before the 2019 flare-up of protests, the PMCs were in Venezuela to mostly provide security for Russian business interests like the Russian energy company Rosneft. They assisted in the training of the Venezuelan National Militia and the pro-Maduro Colectivos paramilitaries in 2018.[42] Russian ambassador to Venezuela, Vladimir Zayemsky denied the report of the existence of Wagner in Venezuela.[307]

Possible activities

Moldova

Amid reports in March 2023 claiming Russia was plotting the toppling of the government of Moldova, and a subsequent anti-government demonstration, the Moldovan Border Police reported it had detained and deported an alleged member of the Wagner Group at Chisinau Airport.[308][309]

Nagorno-Karabakh

Several days after Russian media reported that Russian PMCs were ready to fight against Azerbaijan in Nagorno-Karabakh,[310] a source within the Wagner Group, as well as Russian military analyst Pavel Felgenhauer, reported Wagner contractors were sent to support armed forces of the partially recognized Republic of Artsakh against Azerbaijan during the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh War as ATGM operators.[311][312] However, Bellingcat reported that the Wagner Group was not present in Nagorno-Karabakh, pointing to the Reverse Side of the Medal (RSOTM) public channel, used by Russian PMCs, including Wagner. RSOTM posted two images and a song alluding to the possibility of Wagner PMCs arriving in Nagorno-Karabakh, but Bellingcat determined the images were unrelated.[313]

Following the end of the war, retired military captain Viktor Zlobov stated Wagner PMCs took a significant role in managing to preserve the territory that remained under Armenian control during the conflict and were the ones mostly responsible for the Armenians managing to keep control of the town of Shusha for as long as they did before it was ultimately captured by Azerbaijan during the major battle that took place. Turkey reported that 380 «blondes with blue eyes» took part in the conflict on the side of Artsakh, while some Russian publications put the number of Wagner PMCs who arrived in the region in early November at 500. 300 of these were said to have taken part in the Battle of Shusha[314] and a photo of a Wagner PMC, apparently taken in front a church in Shusha during the war, appeared on the internet the following month.[315]

The Russian news outlet OSN reported the arrival of the PMCs was also one of the factors that led to Azerbaijan’s halt of their offensive against Nagorno-Karabakh.[316]

Serbia

A Russian news video claiming to show Serbian «volunteers» being training by the Wagner Group to fight alongside Russian troops in Ukraine has prompted outrage in Serbia.[317] Serbia’s president, Aleksandar Vučić, reacted angrily on national TV, asking why the Wagner Group would call on anyone from Serbia when it is against the country’s regulations.[317] It is illegal for Serbians to take part in conflicts abroad.[317]

Other

According to information from leaked US intelligence findings, Wagner has sought to expand its operations into Haiti, reaching out to the embattled Haitian government with a proposal to combat gangs on behalf of the government.[318]

In June 2023 an email from the Wagner Group suggested that the group had plans involving the Chatham Islands east of the New Zealand mainland, following a television interview with Prigozhin when a map on the wall behind him had a coloured pin into the position of the islands.[319]

Casualties

| Conflict | Period | Wagner casualties | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| War in Donbas | June 2014 – October 2015 | 30–80 killed[206] | The Ukrainian SBU claimed 36 PMCs were killed[320] during the fighting at Luhansk International Airport (15) and the Battle of Debaltseve (21).[17] Four of those who died in the battle for the airport were killed at the nearby village of Khryashchevatoe.[321] |

| Syrian civil war | September 2015 – December 2017 | 151–201 killed[322][323][26] 900+ wounded[322] |

CIT reported a conservative estimate of at least 101 being killed between October 2015 and mid-December 2017.[88] The founder of CIT stated the death toll was at least 100–200,[323] while another CIT blogger said at least 150 were killed and more than 900 were wounded.[322] Fontanka reported a conservative estimate of at least 73 dead by mid-December 2017,[88] 40–60 of which died during the first several months of 2017.[324] A former PMC officer stated no fewer than 100 died by the end of August 2016.[121] One more PMC was killed in late December 2017.[26] |

| Syrian civil war – Battle of Khasham | 7 February 2018 | 14–64 killed (confirmed)[325][326] 80–100 killed (estimated)[327][328] 100–200 wounded[327][328] |

The Ukrainian SBU claimed 80 were killed and 100 wounded,[328] naming 64 of the dead.[326] A source with ties to Wagner and a Russian military doctor claimed 80–100 were killed and 200 wounded.[327] A Russian journalist believed between 20 and 25 died,[329] while similarly CIT estimated a total of between 20 and 30 had died.[330] The Novaya Gazeta newspaper reported 13 dead, while the Baltic separate Cossack District ataman stated no more than 15–20 died.[331] Wagner commanders put the death toll at 14 or 15 at the most.[325][332][14] |

| Syrian civil war | May 2018–present | 17 killed[333] | In addition, three PMCs belonging to the Russian private military company Shield also died mid-June 2019. Two of the three were former Wagner members.[334] |

| Central African Republic Civil War | March 2018–present | 33 killed[335] | |

| Sudanese Revolution | December 2018 – January 2019 | 2 killed[336] | |

| Insurgency in Cabo Delgado | September 2019 – March 2020 | 11 killed[337][338] | |

| Second Libyan Civil War | September 2019 – October 2020 | 21–48 killed[339] | Russian blogger Mikhail Polynkov claimed no less than 100 PMCs had been killed by early April 2020. However, this was not independently confirmed.[340] |

| Mali War | December 2021–present | 1 killed (confirmed)[341] | The death of one more Russian «mercenary» and two «foreign soldiers», said to be Russian, were also reported in two incidents in Jan. and March 2022.[45][342] |

| Russian invasion of Ukraine | 24 February 2022–present | 8,628 killed (confirmed) 9,000+ killed, 21,000+ wounded (estimated) |

The Mediazona outlet and BBC News Russian confirmed by names the deaths of 8,628 PMCs, including 6,073 recruited convicts.[343][344] This number possibly includes members of the PMC Redut, which counts among its members former Wagner commanders,[345] as well as convicts.[346] The US estimated that about 9,000 Wagner fighters had been killed and 21,000 had been wounded as of the middle of February 2023, with about half of those occurring since the middle of December 2022.[243] |

Families of killed PMCs are prohibited from talking to the media under a non-disclosure that is a prerequisite for them to get compensation from the company. The standard compensation for the family of a killed Wagner employee is up to 5 million rubles (about 80,000 dollars), according to a Wagner official.[121] In contrast, the girlfriend of a killed fighter stated the families are paid between 22,500 and 52,000 dollars depending on the killed PMC’s rank and mission.[347] In mid-2018, Russian military veterans urged the Russian government to acknowledge sending private military contractors to fight in Syria, in an attempt to secure financial and medical benefits for the PMCs and their families.[348]

The Sogaz International Medical Centre in Saint Petersburg, a clinic owned by the large insurance company AO Sogaz, has treated PMCs who had been injured in combat overseas since 2016. The company’s senior officials and owners are either relatives of Russian president Putin or others linked to him. The clinic’s general director, Vladislav Baranov, also has a business relationship with Maria Vorontsova, Putin’s eldest daughter.[349]

On 12 April 2018, investigative Russian journalist Maksim Borodin was found badly injured at the foot of his building, after falling from his fifth-floor balcony in Yekaterinburg.[350] He was hospitalized in a coma and died of his injuries three days later on 15 April.[89] In the weeks before his death, Borodin gained national attention[351] when he wrote about the deaths of Wagner PMCs in the battle with US-backed forces in eastern Syria in early February, that also involved US air-strikes.[350]

Sanctions

Prigozhin was sanctioned by the United States Department of the Treasury in December 2016 for Russia’s involvement in the Ukraine conflict,[352][353] and by the European Union (EU) and the United Kingdom in October 2020 for links to Wagner activities in Libya.[354]

The US Department of the Treasury also imposed sanctions on the Wagner Group and Utkin personally in June 2017.[355] The designation of the US Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control listed the company and Dmitriy Utkin under the «Designations of Ukrainian Separatists (E.O. 13660)» heading and referred to him as «the founder and leader of PMC Wagner».[356] Further sanctions were implemented against the Wagner Group in September 2018,[357][358][359] and July 2020.[284] In December 2021, the EU imposed sanctions against the Wagner Group and eight individuals and three entities connected with it, for committing «serious human rights abuses, including torture and extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions and killings, or in destabilising activities in some of the countries they operate in, including Libya, Syria, Ukraine (Donbas) and the Central African Republic.»[360][361][362]

Following the Russian invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022, Canada, Australia, Japan, Switzerland and New Zealand had sanctioned the group.[363][364][365][366][367] In addition, in late January 2023, the US announced it would designate Wagner as a «significant transnational criminal organization», enabling further tougher sanctions to be implemented against the group.[368][369][370]

In early 2023, the US was reported to be working with Egypt and the UAE to put pressure on the military leaders of Sudan and Libya to end their relationship with the Wagner Group and expel them from the countries. The Wagner Group had supported the UAE’s and Saudi Arabia’s allies in Sudan and Libya. In addition, the Wagner PMCs in Libya were mainly funded by the UAE.[371]

On 4 July 2023, the Parliamentary Assembly of the OSCE recognized Wagner as a terrorist organization and Russia as a state sponsor of terrorism.

On 24 July, the US also sanctioned three Malian officials for facilitating the Wagner Group’s operations in their country.[372]

Plane crash

On 23 August 2023, Wagner leaders Yevgeny Prigozhin and Dmitry Utkin died in a plane crash in Tver Oblast, Russia. While the cause of the crash is unknown, The Wall Street Journal cited sources within the US government as saying that the crash was likely caused by a bomb onboard or «some other form of sabotage».[373] Early reports suggested a missile strike, but the Journal cited three veteran aviation experts who said that the visual evidence indicates a catastrophic structural failure not attributable to a missile.[374] Meduza discounted the possibility of a surface-to-air missile (SAM) strike, saying that the aircraft was flying too high to be hit by a short-range man-portable air-defense system, while a more potent medium-range SAM such as those operated by Russian forces in the area would cause much more severe and readily identifiable damage.[375] The United States Department of Defense press secretary Patrick Ryder said that the Pentagon had no indication that the plane had been shot down by a SAM, calling it false information.[376][377] Experts consulted by The New York Times said that the size of the debris field—with the fuselage being found some 3 km (2 mi) from the empennage—suggests a catastrophic structural failure that could not be caused by a simple mechanical problem.[378]

Far-right elements

Various elements of the Wagner Group have been linked to far-right extremism, including white supremacy and neo-Nazism.[379][380][381][382] Some founding members of Wagner belong to the far-right ultranationalist Russian Imperial Movement.[383] Wagner’s first commander, Dmitry Utkin,[136] was reportedly a neo-Nazi and had several Nazi tattoos,[384][385][380][382] greeted subordinates by saying «Heil!», worn a Wehrmacht field cap around the unit’s training grounds, and occasionally signed his name with the two lightning bolt insignia of the Nazi SS.[136]

In 2021, the Foreign Policy report noted the origin of the name «Wagner» to be unknown.[99] Others say the group’s name comes from Utkin’s own call sign «Wagner», reportedly after the German composer Richard Wagner, which Utkin is said to have chosen due to his passion for the Third Reich (Wagner being Adolf Hitler’s favorite composer).[386][380] Members of Wagner Group said Utkin was a Rodnover, a follower of Slavic native faith.[387] A Wagner sub-group, «Rusich», was founded by self-proclaimed neo-Nazi Alexey Milchakov and is open about its far-right ideology.[140][388][389][144] Wagner members have also left neo-Nazi graffiti on the battlefield,[381][338] such as swastikas and the SS emblem.[383][382]

However, Erica Gaston, a senior policy adviser at the UN University Centre for Policy Research, noted that the Wagner Group is not driven by ideology, but is rather a network of mercenaries «linked to the Russian security state».[390][391]

Awards and honors

Wagner PMCs have received state awards[19] in the form of military decorations[106] and certificates signed by Russian president Putin.[392] Wagner commanders Andrey Bogatov and Andrei Troshev were awarded the Hero of the Russian Federation honor for assisting in the first capture of Palmyra in March 2016. Bogatov was seriously injured during the battle. Meanwhile, Alexander Kuznetsov and Dmitry Utkin had reportedly won the Order of Courage four times.[102] Family members of killed PMCs also received medals from Wagner itself, with the mother of one killed fighter being given two medals, one for «heroism and valour» and the other for «blood and bravery».[393] A medal for conducting operations in Syria was also issued by Wagner to its PMCs.[394]

In mid-December 2017, a powerlifting tournament was held in Ulan-Ude, capital city of the Russian Republic of Buryatia, which was dedicated to the memory of Vyacheslav Leonov, a Wagner PMC who was killed during the campaign in Syria’s Deir ez-Zor province.[395][396] The same month, Russia’s president signed a decree establishing International Volunteer Day in Russia, as per the UN resolution from 1985, which will be celebrated annually every 5 December. The Russian Poliksal news site associated the Russian celebration of Volunteer Day with honoring Wagner PMCs.[397]

In late January 2018, an image emerged of a monument in Syria, dedicated to «Russian volunteers».[398] The inscription on the monument in Arabic read: «To Russian volunteers, who died heroically in the liberation of Syrian oil fields from ISIL».[399][400] The monument was located at the Haiyan plant, about 50 kilometers from Palmyra,[401] where Wagner PMCs were deployed.[402] An identical monument was also erected in Luhansk in February 2018.[403] In late August 2018, a chapel was built near Goryachy Klyuch, Krasnodar Krai, in Russia in memory of Wagner PMCs killed in fighting against ISIL in Syria. For each of those killed a candle is lit in the chapel.[404] Towards the end of November 2018, it was revealed that a third monument, also identical to the two in Syria and Luhansk, was erected in front of the chapel, which is a few dozen kilometers from the PMC’s training facility at Molkin.[405][unreliable source]

The leadership of the Wagner Group and its military instructors were reportedly invited to attend the military parade on 9 May 2018, dedicated to Victory Day.[127]

On 14 May 2021, a Russian movie inspired by the Russian military instructors in the Central African Republic premiered at the national stadium in Bangui.[406] Titled The Tourist, it depicts a group of Russian military advisors sent to the CAR on the eve of presidential elections and, following a violent rebellion, they defend locals against the rebels. The movie was reportedly financed by Prigozhin to improve the Wagner Group’s reputation and included some Wagner PMCs as extras.[407] Six months later, a monument to the Russian military was erected in Bangui.[408] In late January 2022, a second movie about the Russian PMCs had its premiere. The film, titled Granit, showed the true story of the contractors’ mission to the Cabo Delgado region of Mozambique in 2019, against Islamist militants.[409]

Notable members

- Vladimir Andanov was wanted for a killing in Libya.[410] Andanov was reportedly killed by a Ukrainian sniper in Ukraine.[411]

- Alexey Milchakov

- Andrey Medvedev

Citations

- ^ a b Иванов, Геннадий (17 April 2023). «Борьба за справедливость: ЧВК «Вагнер» изменила девиз на боевых знаменах — Петербургская газета» (in Russian). Retrieved 25 August 2023.

- ^ «Зеленский заявил, что ему стыдно за операцию по «вагнеровцам» – ТАСС». TACC.

- ^ a b «Грубо говоря, мы начали войну Как отправка ЧВК Вагнера на фронт помогла Пригожину наладить отношения с Путиным — и что такое «собянинский полк». Расследование «Медузы» о наемниках на войне в Украине». Meduza.

- ^ ««Музыканты» едут в Африку стрелять». Daily Storm. 2 November 2017.

- ^ https://www.mk.ru/politics/2023/08/23/readovka-chvk-vagner-gotovit-zayavlenie-posle-krusheniya-samoleta-prigozhina.html Readovka: ЧВК «Вагнер» готовит заявление после крушения самолета Пригожина

- ^ https://www.bbc.com/russian/articles/crg74ypq81po «Мы из телеграма всё узнавали, как и вы». Командир ЧВК «Вагнер» рассказывает, как для них прошел мятеж и что будет с наемниками дальше

- ^ a b c d e f Faulkner, Christopher (June 2022). Cruickshank, Paul; Hummel, Kristina (eds.). «Undermining Democracy and Exploiting Clients: The Wagner Group’s Nefarious Activities in Africa» (PDF). CTC Sentinel. West Point, New York: Combating Terrorism Center. 15 (6): 28–37. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 July 2022. Retrieved 16 August 2022.

- ^ Light, Felix (5 May 2023). «Russian ex-deputy defence minister joins Wagner as feud escalates, war bloggers report». Reuters.com.

- ^ a b Gostev, Aleksandr; Coalson, Robert (16 December 2016). «Russia’s Paramilitary Mercenaries Emerge From The Shadows». Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- ^ Watson, Ben; Hlad, Jennifer (22 December 2022). «Today’s D Brief: Zelenskyy thanks Americans, lawmakers; North Korea sent arms to Wagner, WH says; Breaking down the omnibus; Germany’s year ahead; And a bit more». Defense One.

- ^ Rai, Arpan (21 April 2022). «Nearly 3,000 of Russia’s notorious Wagner mercenary group have been killed in the war, UK MPs told». Independent.

- ^ a b «Putin Wants to Win, But Not at All Costs». Bloomberg. 6 December 2017. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

- ^ a b c d Quinn, Allison (30 March 2016). «Vladimir Putin sent Russian mercenaries to ‘fight in Syria and Ukraine’«. The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 4 August 2017.

- ^ a b Сергей Хазов-Кассиа (7 March 2018). «Проект ‘Мясорубка’. Рассказывают три командира «ЧВК Вагнера»«. Радио Свобода (in Russian). Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty.

- ^ a b «Revealed: Russia’s ‘Secret Syria Mercenaries’«. Sky News. 10 August 2016. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- ^ a b c «Russian Mercenaries in Syria». Warsaw Institute Foundation. 22 April 2017. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- ^ a b c «SBU exposes involvement of Russian ‘Wagner PMC’ headed by Utkin in destroying Il-76 in Donbas, Debaltseve events – Hrytsak». Interfax-Ukraine. 7 October 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ^ Sautreuil, Pierre (9 March 2016). «Believe It or Not, Russia Dislikes Relying on Military Contractors». War Is Boring. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f Korotkov, Denis (29 March 2016). Они сражались за Пальмиру (in Russian). Fontanka.ru. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- ^ a b Karouny, Mariam (20 October 2015). «Three Russians killed in Syria: pro-government source». Reuters. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- ^ Maria Tsvetkova; Anton Zverev (3 November 2016). «Russian Soldiers Are Secretly Dying In Syria». HuffPost. Retrieved 19 February 2018.

- ^ a b Leviev, Ruslan (22 March 2017). «They fought for Palmyra… again: Russian mercenaries killed in battle with ISIS». Conflict Intelligence Team. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- ^ Tomson, Chris (21 September 2017). «VIDEO: Russian Army intervenes in northern Hama, drives back Al-Qaeda militants». al-Masdar News. Archived from the original on 12 June 2019. Retrieved 24 September 2017.

- ^ a b «The media reported the death of another soldier PMC Wagner in Syria». en.news-4-u.ru. Archived from the original on 1 March 2021. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ^ Dmitriy. «В боях в Сирии погиб уроженец Оренбурга Сергей Карпунин». geo-politica.info. Archived from the original on 19 September 2020. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ^ a b c «Еще один доброволец из Томской области погиб в Сирии». vtomske.ru. 15 January 2018. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

- ^ «Russians dead in ‘battle’ in Syria’s east». Yahoo! News. Archived from the original on 9 November 2020. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- ^ Aboufadel, Leith (13 February 2018). «US attack on pro-gov’t forces in Deir Ezzor killed more than 10 Russians (photos)». Archived from the original on 10 February 2018. Retrieved 13 February 2018.

- ^ a b «ЧВК «Вагнер» не дала боевикам уничтожить мирное население Восточной Гуты – ИА REX».

- ^ «In pictures: Russian snipers deployed near Idlib front as offensive approaches». Al-Masdar News. 1 May 2019. Archived from the original on 11 August 2020. Retrieved 1 May 2019.

- ^ a b «Появилось видео из Судана, где российские наемники тренируют местных военных». Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ^ a b «Beyond Syria and Ukraine: Wagner PMC Expands Its Operations to Africa». Jamestown.

- ^ Gostev, Alexander (25 April 2018). Кремлевская «Драка за Африку». Наемники Пригожина теперь и в джунглях. Радио Свобода (in Russian). Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Retrieved 26 April 2018.

- ^ Lagos, Neil Munshi in. «Central African Republic troops beat back rebels with Russian help». The Irish Times.

- ^ «Central African Republic: Abuses by Russia-Linked Forces». Human Rights Watch. 3 May 2022.

- ^ «Putin Plants Troops, Weapons in Libya to Boost Strategic Hold». Al Bawaba.

- ^ «Новый плацдарм: что известно о переброске российских военных в Ливию». РБК. 9 October 2018.

- ^ Suchkov, Maxim (12 October 2018). «Analysis: Reports on Russian troops in Libya spark controversy». Al-Monitor.

- ^ a b «Putin-Linked Mercenaries Are Fighting on Libya’s Front Lines».

- ^ «Wagner PMC is secret detachment of Russia’s General Staff of Armed Forces – confirmed by mercenaries’ ID papers, says SBU Head Vasyl Hrytsak. Now we’ll only have to wait for information from Russian officials as to which particular «Cathedral» in Sudan or :: Security Service of Ukraine». 29 January 2019. Archived from the original on 29 January 2019.

- ^ a b c «Exclusive: Kremlin-linked contractors help guard Venezuela’s Maduro – sources». Reuters. 25 January 2019.

- ^ a b «Geopolitical debts Why Russia is really sending military advisers and other specialists to Venezuela». Meduza.

- ^ a b ««War ‘declared'»: Report on latest military operations in Mocimboa da Praia and Macomia – Carta». Mozambique.

- ^ France, U.K., Partners Say Russia-Backed Wagner Deployed in Mali

Mali: West condemns Russian mercenaries ‘deployment’ - ^ a b c «Russian mercenaries in Mali : Photos show Wagner operatives in Segou». France 24. 11 January 2022.

- ^ a b «Malian, foreign soldiers allegedly killed hundreds in town siege -rights group». news.yahoo.com. 5 April 2022.

- ^ a b Clark, Mason; Barros, George; Hird, Karolina (20 April 2022). «Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, April 20». Institute for the Study of Warfare.

- ^ a b [ENG] Ukrainian soldiers captured by Wagner Group in Popasnaya 🇷🇺🏹 🇺🇦 – via YouTube.

- ^ a b Yaroslav Trofimov (10 May 2022). «Nearly Encircled, Ukraine’s Last Stronghold in Luhansk Resists Russian Onslaught». The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 14 May 2022. Retrieved 11 May 2022.

- ^ a b «Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, June 23». 23 June 2022. Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- ^ a b Russia used private mercenaries to reinforce frontline, British intelligence says». Yahoo! News.

- ^ «Estonia’s parliament declares Russia a ‘terrorist regime’«. www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ «French parliament designates Wagner a ‘terrorist group». Politico. 11 May 2023.

- ^ «Lithuania designates Russia’s Wagner as terrorist organisation». www.lrt.lt. Lithuanian National Radio and Television. 14 March 2023. Retrieved 14 March 2023.

- ^ «The Seimas: «Russia’s private military company Wagner is a terrorist organisation»«. www.lrs.lt. Seimas. 14 March 2023. Retrieved 26 June 2023.

- ^ «Ukraine’s Parliament Recognizes Wagner as Transnational Criminal Organization». Kyiv Post. 6 February 2023. Retrieved 25 May 2023.

- ^ Holden, Michael; Suleiman, Farouq; M, Muvija; Ravikumar, Sachin (15 September 2023). «UK officially proscribes Russia’s Wagner as terrorist organisation». Reuters. Retrieved 15 September 2023.

- ^ «OSCE Parliamentary Assembly recognizes Russia as state sponsor of terrorism». The Kyiv Independent. 4 July 2023. Retrieved 4 July 2023.

- ^ «Russia’s Paramilitary Mercenaries Emerge from the Shadows».

- ^ «Wagner mutiny: Group fully funded by Russia, says Putin». BBC News. 27 June 2023. Retrieved 27 June 2023.

- ^ «What is the Wagner Group, Russia’s mercenary organisation?». The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 16 March 2022.

«From a legal perspective, Wagner doesn’t exist,» says Sorcha MacLeod

- ^ a b c d «Band of Brothers: The Wagner Group and the Russian State». Center for Strategic and International Studies. 21 September 2020.

- ^ Brimelow, Ben. «Russia is using mercenaries to make it look like it’s losing fewer troops in Syria». Business Insider. Retrieved 28 May 2022.

- ^ a b Ma, Alexandra (9 March 2022). «Ukraine posts image of dog tag it said belonged to a killed mercenary from the Wagner Group, said to be charged with assassinating Zelenskyy». Business Insider.

- ^ a b c Pavlova, Anna; Nesterova, Yelizaveta (6 August 2022). Tkachyov, Dmitry (ed.). «‘В первую очередь интересуют убийцы и разбойники — вам у нас понравится’. Похоже, Евгений Пригожин лично вербует наемников в колониях» [‘We are primarily interested in killers and brigands—you will like it with us’. It seems as if Yevgeny Prigozhin is personally recruiting mercenaries in penal colonies]. Mediazona (in Russian). Archived from the original on 6 August 2022. Retrieved 7 August 2022.

- ^ a b Quinn, Allison (6 August 2022). «‘Putin’s Chef’ Is Personally Touring Russian Prisons for Wagner Recruits to Fight in Ukraine, Reports Say». The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on 7 August 2022. Retrieved 7 August 2022.

- ^ a b «Today’s D Brief: Zelenskyy thanks Americans, lawmakers; North Korea sent arms to Wagner, WH says; Breaking down the omnibus; Germany’s year ahead; And a bit more». Defense One. 22 December 2022. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- ^ a b «Что известно о потерях России за 10 месяцев войны в Украине». BBC News Russian. 23 December 2022. Retrieved 23 December 2022.

- ^ a b «Russia-supporting Wagner Group mercenary numbers soar». BBC News. 22 December 2022.

- ^ a b «How Russia’s Wagner Group funds its role in Putin’s Ukraine war by plundering Africa’s resources». CBS News. 16 May 2023.

- ^ Walsh, Declan (27 June 2021). «Russian Mercenaries Are Driving War Crimes in Africa, U.N. Says». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- ^ «SBU releases new evidence of Russian Wagner fighters’ involvement in war crimes against Ukraine». unian.info. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- ^ «What is Russia’s Wagner Group of mercenaries in Ukraine?». BBC News. 5 April 2022.

- ^ «Головорезы (21+)». Новая газета – Novayagazeta.ru. 20 November 2019.

- ^ «Man who filmed beheading of Syrian identified as Russian mercenary». The Guardian. 21 November 2019.

- ^ a b c «Putin ally Yevgeny Prigozhin admits founding Wagner mercenary group». the Guardian. 26 September 2022. Retrieved 26 September 2022.

- ^ a b «Russia’s Prigozhin admits link to Wagner mercenaries for first time». Reuters. 26 September 2022. Retrieved 26 September 2022.

- ^ «Wagner chief accuses Moscow of lying to public about Ukraine». The Guardian. 23 June 2023.

- ^ Roth, Andrew; Sauer, Pjotr (25 June 2023). «Wagner boss to leave Russia as reports say US spy agencies picked up signs of planned uprising days ago». The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 25 June 2023.

- ^ Seddon, Max (23 August 2023). «Yevgeny Prigozhin was passenger on crashed plane, Russian officials say». Financial Times. Retrieved 23 August 2023.

- ^ Troianovski, Anton; Barnes, Julian E; Schmitt, Eric (24 August 2023). «‘It’s Likely Prigozhin Was Killed,’ Pentagon Says». The New York Times. Archived from the original on 27 August 2023. Retrieved 27 August 2023.

- ^ Andrew S. Bowen (23 March 2023). Russia’s Wagner Private Military Company (PMC) (Report). Congressional Research Service.

- ^ a b c d e «In Prigozhin’s shadow, the Wagner Group leader who stays out of the spotlight». Global News. 29 June 2023.