|

Leonid Brezhnev |

||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Леонид Брежнев |

||||||||||||||||||||

Official portrait, 1972 |

||||||||||||||||||||

| General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union[a] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 14 October 1964 – 10 November 1982 |

||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Nikita Khrushchev (as First Secretary) |

|||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Yuri Andropov | |||||||||||||||||||

| Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet | ||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 16 June 1977 – 10 November 1982 |

||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Nikolai Podgorny | |||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Vasily Kuznetsov (acting) Yuri Andropov |

|||||||||||||||||||

| In office 7 May 1960 – 15 July 1964 |

||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Kliment Voroshilov | |||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Anastas Mikoyan | |||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | 19 December 1906 Kamenskoye, Ekaterinoslav Governorate, Russian Empire (now Kamianske, Ukraine) |

|||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 10 November 1982 (aged 75) Zarechye, Moscow Oblast, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union |

|||||||||||||||||||

| Resting place | Kremlin Wall Necropolis, Moscow | |||||||||||||||||||

| Nationality | Soviet | |||||||||||||||||||

| Political party | CPSU (1929–1982) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Spouse |

Viktoria Denisova (m. 1928) |

|||||||||||||||||||

| Children | Galina Brezhneva (daughter) Yuri Brezhnev (son) |

|||||||||||||||||||

| Residence(s) | Zarechye, Moscow | |||||||||||||||||||

| Profession |

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Awards |

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Atheist | |||||||||||||||||||

| Signature |  |

|||||||||||||||||||

| Military service | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Allegiance | Soviet Union | |||||||||||||||||||

| Branch/service | Red Army Soviet Army |

|||||||||||||||||||

| Years of service | 1941–1982 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Rank | Marshal of the Soviet Union (1976–1982) |

|||||||||||||||||||

| Commands | Soviet Armed Forces | |||||||||||||||||||

| Battles/wars |

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Central institution membership

Other political offices held

Military offices held

Leader of the Soviet Union

|

||||||||||||||||||||

Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev[b] (19 December 1906 – 10 November 1982)[4] was a Soviet politician who served as General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1964 until his death in 1982, and Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet (head of state) from 1960 to 1964 and again from 1977 to 1982. His 18-year term as General Secretary was second only to Joseph Stalin’s in duration. To this day, the quality of Brezhnev’s tenure as General Secretary remains debated by historians. While his rule was characterized by political stability and significant foreign policy successes, it was also marked by corruption, inefficiency, economic stagnation, and rapidly growing technological gaps with the West.

Brezhnev was born to a working-class family in Kamenskoye (now Kamianske, Ukraine) within the Yekaterinoslav Governorate of the Russian Empire. After the results of the October Revolution were finalized with the creation of the Soviet Union, Brezhnev joined the Communist party’s youth league in 1923 before becoming an official party member in 1929. When Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941, he joined the Red Army as a commissar and rose rapidly through the ranks to become a major general during World War II. Following the war’s end, Brezhnev was promoted to the party’s Central Committee in 1952 and rose to become a full member of the Politburo by 1957. In 1964, he garnered enough power to replace Nikita Khrushchev as First Secretary of the CPSU, the most powerful position in the country.

During his tenure, Brezhnev’s conservative, pragmatic approach to governance significantly improved the Soviet Union’s international standing while stabilizing the position of its ruling party at home. Whereas Khrushchev often enacted policies without consulting the rest of the Politburo, Brezhnev was careful to minimize dissent among the party leadership by reaching decisions through consensus as he restored the collective leadership in the USSR. Additionally, while pushing for détente between the two Cold War superpowers, he achieved nuclear parity with the United States and strengthened the Soviet Union’s dominion over Central and Eastern Europe. Furthermore, the massive arms buildup and widespread military interventionism under Brezhnev’s leadership substantially expanded the Soviet Union’s influence abroad (particularly in the Middle East and Africa), although these endeavors would prove to be costly and would drag on the Soviet economy in the later years.

Conversely, Brezhnev’s disregard for political reform ushered in an era of societal decline known as the Brezhnev Stagnation. In addition to pervasive corruption and falling economic growth, this period was characterized by an increasing technological gap between the Soviet Union and the United States. Upon coming to power in 1985, Mikhail Gorbachev denounced Brezhnev’s government for its inefficiency and inflexibility before implementing policies to liberalise the Soviet Union.

After 1975, Brezhnev’s health rapidly deteriorated and he increasingly withdrew from international affairs, while keeping his hold on power. He died on 10 November 1982 and was succeeded as general secretary by Yuri Andropov.

Early life and early career[edit]

1906–1939: Origins[edit]

Brezhnev was born on 19 December 1906 in Kamenskoye (now Kamianske, Ukraine) within the Yekaterinoslav Governorate of the Russian Empire, to metalworker Ilya Yakovlevich Brezhnev (1874–1934) and his wife, Natalia Denisovna Mazalova (1886–1975). His parents lived in Brezhnevo (Kursky District, Kursk Oblast, Russia) before moving to Kamenskoye. Brezhnev’s ethnicity was given as Ukrainian in some documents, including his passport,[5][6][7] and Russian in others.[8][9] A statement confirming that he regarded himself as a Russian can be found in his book Memories (1979), where he wrote: «And so, according to nationality, I am Russian, I am a proletarian, a hereditary metallurgist.»[10]

Like many youths in the years after the Russian Revolution of 1917, he received a technical education, at first in land management and then in metallurgy. He graduated from the Kamenskoye Metallurgical Technicum in 1935[11] and became a metallurgical engineer in the iron and steel industries of eastern Ukraine.

Brezhnev joined the Communist Party youth organisation, the Komsomol, in 1923, and the Party itself in 1929.[9] From 1935 to 1936 he completed the compulsory term of military service. After taking courses at a tank school, he served as a political commissar in a tank factory.

During Stalin’s Great Purge, Brezhnev was one of many apparatchiks who exploited the resulting openings in the government and the party to advance rapidly in the regime’s ranks.[9] In 1936, he became director of the Dniprodzerzhynsk Metallurgical Technicum (a technical college) and was transferred to the regional center of Dnipropetrovsk. In May 1937, he became deputy chairman of the Kamenskoye city soviet. In May 1938, after Nikita Khrushchev had taken control of the Ukrainian communist party, he was appointed head of the propaganda department of the Dnipropetrovsk regional communist party, and later, in 1939, a regional Party Secretary,[11] in charge of the city’s defense industries. Here, he took the first steps toward building a network of supporters which came to be known as the «Dnipropetrovsk Mafia» that would greatly aid his rise to power.

1941–1945: World War II[edit]

When Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941, Brezhnev was, like most middle-ranking Party officials, immediately drafted. He worked to evacuate Dnipropetrovsk’s industries before the city fell to the Germans on 26 August, and then was assigned as a political commissar. In October, Brezhnev was made deputy of political administration for the Southern Front, with the rank of Brigade-Commissar (Colonel).[12]

When the Germans occupied Ukraine in 1942, Brezhnev was sent to the Caucasus as deputy head of political administration of the Transcaucasian Front. In April 1943 he became head of the Political Department of the 18th Army. Later that year, the 18th Army became part of the 1st Ukrainian Front, as the Red Army regained the initiative and advanced westward through Ukraine.[13] The Front’s senior political commissar was Nikita Khrushchev, who had supported Brezhnev’s career since the prewar years. Brezhnev had met Khrushchev in 1931, shortly after joining the Party, and as he continued his rise through the ranks, he became Khrushchev’s protégé.[14] At the end of the war in Europe, Brezhnev was chief political commissar of the 4th Ukrainian Front, which entered Prague in May 1945, after the German surrender.[12]

Rise to power[edit]

Promotion to the Central Committee[edit]

Brezhnev left the Soviet Army with the rank of major general in August 1946. He had spent the entire war as a political commissar rather than a military commander. In May 1946, he was appointed the first secretary of the Zaporizhzhia regional party committee, where his deputy was Andrei Kirilenko, one of the most important members of the Dnipropetrovsk Mafia. After working on reconstruction projects in Ukraine, he returned to Dnipropetrovsk in January 1948 as regional first party secretary. In 1950 Brezhnev became a deputy of the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union, the Soviet Union’s highest legislative body. In July that year he was sent to the Moldavian SSR and appointed Party First Secretary of the Communist Party of Moldova,[15] where he was responsible for completing the introduction of collective agriculture. Konstantin Chernenko, a loyal addition to the «mafia», was working in Moldova as head of the agitprop department, and one of the officials Brezhnev brought with him from Dnipropetrovsk was the future USSR Minister of the Interior, Nikolai Shchelokov. In 1952 he had a meeting with Stalin, after which Stalin promoted Brezhnev to the Communist Party’s Central Committee as a candidate member of the Presidium (formerly the Politburo)[16] and made him one of ten secretaries of the Central Committee. Stalin died in March 1953 and, in the reorganization that followed, Brezhnev was demoted to first deputy head of the political directorate of the Army and Navy.

Advancement under Khrushchev[edit]

Brezhnev’s patron Khrushchev succeeded Stalin as General Secretary, while Khrushchev’s rival Georgy Malenkov succeeded Stalin as Chairman of the Council of Ministers. Brezhnev sided with Khrushchev against Malenkov, but only for several years. In February 1954, he was appointed second secretary of the Communist Party of the Kazakh SSR, and was promoted to General Secretary in May, following Khrushchev’s victory over Malenkov. On the surface his brief was simple: to make the new lands agriculturally productive. In reality, Brezhnev became involved in the development of the Soviet missile and nuclear arms programs, including the Baykonur Cosmodrome. The initially successful Virgin Lands Campaign soon became unproductive and failed to solve the growing Soviet food crisis. Brezhnev was recalled to Moscow in 1956. The harvest in the years following the Virgin Lands Campaign was disappointing, which would have hurt his political career had he remained in Kazakhstan.[15]

In February 1956 Brezhnev returned to Moscow and was made candidate member of the Politburo assigned in control of the defence industry, the space program including the Baykonur Cosmodrome, heavy industry, and capital construction.[17] He was now a senior member of Khrushchev’s entourage, and in June 1957 he backed Khrushchev in his struggle with Malenkov’s Stalinist old guard in the Party leadership, the so-called «Anti-Party Group». Following the Stalinists’ defeat, Brezhnev became a full member of the Politburo. In May 1960, he was promoted to the post of Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet, making him the nominal head of state, although the real power resided with Khrushchev as First Secretary of the Soviet Communist Party and Premier.[18]

Replacement of Khrushchev as Soviet leader[edit]

Khrushchev’s position as Party leader was secure until about 1962, but as he aged, he grew more erratic and his performance undermined the confidence of his fellow leaders. The Soviet Union’s mounting economic problems also increased the pressure on Khrushchev’s leadership. Brezhnev remained outwardly loyal to Khrushchev, but became involved in a 1963 plot to remove him from power, possibly playing a leading role. Also in 1963, Brezhnev succeeded Frol Kozlov, another Khrushchev protégé, as Secretary of the Central Committee, positioning him as Khrushchev’s likely successor.[19] Khrushchev made him Second Secretary, or deputy party leader, in 1964.[20]

After returning from Scandinavia and Czechoslovakia in October 1964, Khrushchev, unaware of the plot, went on holiday in Pitsunda resort on the Black Sea. Upon his return, his Presidium officers congratulated him for his work in office. Anastas Mikoyan visited Khrushchev, hinting that he should not be too complacent about his present situation. Vladimir Semichastny, head of the KGB,[21] was a crucial part of the conspiracy, as it was his duty to inform Khrushchev if anyone was plotting against his leadership. Nikolay Ignatov, whom Khrushchev had sacked, discreetly requested the opinion of several Central Committee members. After some false starts, fellow conspirator Mikhail Suslov phoned Khrushchev on 12 October and requested that he return to Moscow to discuss the state of Soviet agriculture. Finally, Khrushchev understood what was happening, and said to Mikoyan, «If it’s me who is the question, I will not make a fight of it.»[22] While a minority headed by Mikoyan wanted to remove Khrushchev from the office of First Secretary but retain him as the Chairman of the Council of Ministers, the majority, headed by Brezhnev, wanted to remove him from active politics altogether.[22]

Brezhnev and Nikolai Podgorny appealed to the Central Committee, blaming Khrushchev for economic failures, and accusing him of voluntarism and immodest behavior. Influenced by Brezhnev’s allies, Politburo members voted on 14 October to remove Khrushchev from office.[23] Some members of the Central Committee wanted him to undergo punishment of some kind, but Brezhnev, who had already been assured the office of the General Secretary, saw little reason to punish Khrushchev further.[24] Brezhnev was appointed First Secretary on the same day, but at the time was believed to be a transitional leader, who would only «keep the shop» until another leader was appointed.[25] Alexei Kosygin was appointed head of government, and Mikoyan was retained as head of state.[26] Brezhnev and his companions supported the general party line taken after Stalin’s death but felt that Khrushchev’s reforms had removed much of the Soviet Union’s stability. One reason for Khrushchev’s ouster was that he continually overruled other party members, and was, according to the plotters, «in contempt of the party’s collective ideals». The Soviet newspaper Pravda wrote of new enduring themes such as collective leadership, scientific planning, consultation with experts, organisational regularity and the ending of schemes. When Khrushchev left the public spotlight, there was no popular commotion, as most Soviet citizens, including the intelligentsia, anticipated a period of stabilization, steady development of Soviet society and continuing economic growth in the years ahead.[24]

Political scientist George W. Breslauer has compared Khrushchev and Brezhnev as leaders. He argues they took different routes to build legitimate authority, depending on their personalities and the state of public opinion. Khrushchev worked to decentralize the government system and empower local leadership, which had been wholly subservient; Brezhnev sought to centralize authority, going so far as to weaken the roles of the other members of the Central Committee and the Politburo.[27]

1964–1982: Leader of the Soviet Union[edit]

Consolidation of power[edit]

Alexei Kosygin

Nikolai Podgorny

Upon replacing Khrushchev as the party’s First Secretary, Brezhnev became the de jure supreme authority of the Soviet Union. However, he was initially forced to govern as part of an unofficial Triumvirate (also known by its Russian name Troika) alongside the country’s Premier, Alexei Kosygin, and Nikolai Podgorny, a Secretary of the CPSU Central Committee and later Chairman of the Presidium.[28][29] Due to Khrushchev’s disregard for the rest of the Politburo upon combining his leadership of the party with that of the Soviet government, a plenum of the Central Committee in October 1964 forbade any single individual from holding both the offices of General Secretary and Premier.[24] This arrangement would persist until the late 1970s when Brezhnev firmly secured his position as the most powerful figure in the Soviet Union.

During his consolidation of power, Brezhnev first had to contend with the ambitions of Alexander Shelepin, the former Chairman of the KGB and current head of the Party-State Control Committee. In early 1965, Shelepin began calling for the restoration of «obedience and order» within the Soviet Union as part of his own bid to seize power.[30] Towards this end, he exploited his control over both state and party organs to leverage support within the regime. Recognizing Shelepin as an imminent threat to his position, Brezhnev mobilized the Soviet collective leadership to remove him from the Party-State Control Committee before having the body dissolved altogether on 6 December 1965.[31]

By the end of 1965, Brezhnev had Podgorny removed from the Secretariat, thereby significantly curtailing the latter’s ability to build support within the party apparatus.[32] In the ensuing years, Podgorny’s network of supporters was steadily eroded as the protégés he cultivated in his rise to power were removed from the Central Committee.[33] By 1977, Brezhnev was secure enough in his position to replace Podgorny as head of state and remove him from the Politburo.[34][35]

After sidelining Shelepin and Podgorny as threats to his leadership in 1965, Brezhnev directed his attentions to his remaining political rival, Alexei Kosygin. In the 1960s, U.S. National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger initially perceived Kosygin to be the dominant leader of Soviet foreign policy in the Politburo. Within the same timeframe, Kosygin was also in charge of economic administration in his role as Chairman of the Council of Ministers. However, his position was weakened following his enactment of several economic reforms in 1965 that collectively came to be known within the Party as the «Kosygin reforms». Due largely to coinciding with the Prague Spring (whose sharp departure from the Soviet model led to its armed suppression in 1968), the reforms provoked a backlash among the party’s old guard who proceeded to flock to Brezhnev and strengthened his position within the Soviet leadership.[36] In 1969, Brezhnev further expanded his authority following a clash with Second Secretary Mikhail Suslov who thereafter never challenged his supremacy within the Politburo.[37]

Brezhnev was adept at politics within the Soviet power structure. He was a team player and never acted rashly or hastily. Unlike Khrushchev, he did not make decisions without substantial consultation from his colleagues, and was always willing to hear their opinions.[38] During the early 1970s, Brezhnev consolidated his domestic position. In 1977, he forced the retirement of Podgorny and became once again Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union, making this position equivalent to that of an executive president. While Kosygin remained Premier until shortly before his death in 1980 (replaced by Nikolai Tikhonov as Premier), Brezhnev was the dominant figure in the Soviet Union from the mid-1970s[39] until his death in 1982.[36]

Domestic policies[edit]

Repression[edit]

Brezhnev’s stabilization policy included ending the liberalizing reforms of Khrushchev, and clamping down on cultural freedom.[40] During the Khrushchev years, Brezhnev had supported the leader’s denunciations of Stalin’s arbitrary rule, the rehabilitation of many of the victims of Stalin’s purges, and the cautious liberalization of Soviet intellectual and cultural policy, but as soon as he became leader, Brezhnev began to reverse this process, and developed an increasingly authoritarian and conservative attitude.[41][42]

By the mid-1970s, there were an estimated 5,000 political and religious prisoners across the Soviet Union, living in grievous conditions and suffering from malnutrition. Many of these prisoners were considered by the Soviet state to be mentally unfit and were hospitalized in mental asylums across the Soviet Union. Under Brezhnev’s rule, the KGB infiltrated most, if not all, anti-government organisations, which ensured that there was little to no opposition against him or his power base. However, Brezhnev refrained from the all-out violence seen under Stalin’s rule.[43] The trial of the writers Yuli Daniel and Andrei Sinyavsky in 1966, the first such public trials since Stalin’s reign, marked the reversion to a repressive cultural policy.[41] Under Yuri Andropov the state security service (in the form of the KGB) regained some of the powers it had enjoyed under Stalin, although there was no return to the purges of the 1930s and 1940s, and Stalin’s legacy remained largely discredited among the Soviet intelligentsia.[43]

Economics[edit]

Economic growth until 1973[edit]

| Period | Annual GNP growth (according to the CIA) |

Annual NMP growth (according to Grigorii Khanin) |

Annual NMP growth (according to the USSR) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1960–1965 | 4.8[44] | 4.4[44] | 6.5[44] |

| 1965–1970 | 4.9[44] | 4.1[44] | 7.7[44] |

| 1970–1975 | 3.0[44] | 3.2[44] | 5.7[44] |

| 1975–1980 | 1.9[44] | 1.0[44] | 4.2[44] |

| 1980–1985 | 1.8[44] | 0.6[44] | 3.5[44] |

| [note 1] |

Between 1960 and 1970, Soviet agriculture output increased by 3% annually. Industry also improved: during the Eighth Five-Year Plan (1966–1970), the output of factories and mines increased by 138% compared to 1960. While the Politburo became aggressively anti-reformist, Kosygin was able to convince both Brezhnev and the politburo to leave the reformist communist leader János Kádár of the Hungarian People’s Republic alone because of an economic reform entitled New Economic Mechanism (NEM), which granted limited permission for the establishment of retail markets.[53] In the Polish People’s Republic, another approach was taken in 1970 under the leadership of Edward Gierek; he believed that the government needed Western loans to facilitate the rapid growth of heavy industry. The Soviet leadership gave its approval for this, as the Soviet Union could not afford to maintain its massive subsidy for the Eastern Bloc in the form of cheap oil and gas exports. The Soviet Union did not accept all kinds of reforms, an example being the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968 in response to Alexander Dubček’s reforms.[54] Under Brezhnev, the Politburo abandoned Khrushchev’s decentralization experiments. By 1966, two years after taking power, Brezhnev abolished the Regional Economic Councils, which were organized to manage the regional economies of the Soviet Union.[55]

The Ninth Five-Year Plan delivered a change: for the first time industrial consumer products out-produced industrial capital goods. Consumer goods such as watches, furniture and radios were produced in abundance. The plan still left the bulk of the state’s investment in industrial capital-goods production. This outcome was not seen as a positive sign for the future of the Soviet state by the majority of top party functionaries within the government; by 1975 consumer goods were expanding 9% slower than industrial capital-goods. The policy continued despite Brezhnev’s commitment to make a rapid shift of investment to satisfy Soviet consumers and lead to an even higher standard of living. This did not happen.[56]

During 1928–1973, the Soviet Union was growing economically at a faster pace than the United States and Western Europe. However, objective comparisons are difficult. The USSR was hampered by the effects of World War II, which had left most of Western USSR in ruins, however Western aid and Soviet espionage in the period 1941–1945 (culminating in cash, material and equipment deliveries for military and industrial purposes) had allowed the Russians to leapfrog many Western economies in the development of advanced technologies, particularly in the fields of nuclear technology, radio communications, agriculture and heavy manufacturing. By the early 1970s, the Soviet Union had the world’s second largest industrial capacity, and produced more steel, oil, pig-iron, cement and tractors than any other country.[57] Before 1973, the Soviet economy was expanding at a faster rate than that of the American economy (albeit by a very small margin). The USSR also kept a steady pace with the economies of Western Europe. Between 1964 and 1973, the Soviet economy stood at roughly half the output per head of Western Europe and a little more than one third that of the U.S.[58] In 1973, the process of catching up with the rest of the West came to an end as the Soviets fell further and further behind in computers, which proved decisive for the Western economies.[59] By 1973 the Era of Stagnation was apparent.[60]

Economic stagnation until 1982[edit]

The Era of Stagnation, a term coined by Mikhail Gorbachev, was attributed to a compilation of factors, including the ongoing «arms race»; the Soviet Union’s decision to participate in international trade (thus abandoning the idea of economic isolation) while ignoring changes occurring in Western societies; increased authoritarianism in Soviet society; the invasion of Afghanistan; the bureaucracy’s transformation into an undynamic gerontocracy; lack of economic reform; pervasive political corruption, and other structural problems within the country.[61] Domestically, social stagnation was stimulated by the growing demands of unskilled workers, labor shortages and a decline in productivity and labor discipline. While Brezhnev, albeit «sporadically»,[42] through Alexei Kosygin, attempted to reform the economy in the late 1960s and 1970s, he failed to produce any positive results. One of these reforms was the economic reform of 1965, initiated by Kosygin, though its origins are often traced back to the Khrushchev Era. The reform was ultimately cancelled by the Central Committee, though the Committee admitted that economic problems did exist.[62] After becoming leader of the Soviet Union, Gorbachev would characterize the economy under Brezhnev’s rule as «the lowest stage of socialism».[63]

Based on its surveillance, the CIA reported that the Soviet economy peaked in the 1970s upon reaching 57% of American GNP. However, beginning around 1975, economic growth began to decline at least in part due to the regime’s sustained prioritization of heavy industry and military spending over consumer goods. Additionally, Soviet agriculture was unable to feed the urban population, let alone provide for a rising standard of living which the government promised as the fruits of «mature socialism» and on which industrial productivity depended. Ultimately, the GNP growth rate slowed to 1% to 2% per year. As GNP growth rates decreased in the 1970s from the level held in the 1950s and 1960s, they likewise began to lag behind that of Western Europe and the United States. Eventually, the stagnation reached a point that the United States began growing an average of 1% per year above the growth rate of the Soviet Union.[64]

The stagnation of the Soviet economy was fueled even further by the Soviet Union’s ever-widening technological gap with the West. Due to the cumbersome procedures of the centralized planning system, Soviet industries were incapable of the innovation needed to meet public demand.[65] This was especially notable in the field of computers. In response to the lack of uniform standards for peripherals and digital capacity in the Soviet computer industry, Brezhnev’s regime ordered an end to all independent computer development and required all future models to be based on the IBM/360.[66] However, following the adoption of the IBM/360 system, the Soviet Union was never able to build enough platforms, let alone improve on its design.[67][68] As its technology continued to fall behind the West, the Soviet Union increasingly resorted to pirating Western designs.[66]

The last significant reform undertaken by the Kosygin government, and some believe the pre-perestroika era, was a joint decision of the Central Committee and the Council of Ministers named «Improving planning and reinforcing the effects of the economic mechanism on raising the effectiveness in production and improving the quality of work», more commonly known as the 1979 reform. The reform, in contrast to the 1965 reform, sought to increase the central government’s economic involvement by enhancing the duties and responsibilities of the ministries. With Kosygin’s death in 1980, and due to his successor Nikolai Tikhonov’s conservative approach to economics, very little of the reform was actually carried out.[69]

The Eleventh Five-Year Plan of the Soviet Union delivered a disappointing result: a change in growth from 5 to 4%. During the earlier Tenth Five-Year Plan, they had tried to meet the target of 6.1% growth but failed. Brezhnev was able to defer economic collapse by trading with Western Europe and the Arab World.[64] The Soviet Union still out-produced the United States in the heavy industry sector during the Brezhnev era. Another dramatic result of Brezhnev’s rule was that certain Eastern Bloc countries became more economically advanced than the Soviet Union.[70]

Agricultural policy[edit]

Brezhnev’s agricultural policy reinforced traditional ways of organizing collective farms and enforced output quotas centrally. Although there was a record-high state investment in farming during the 1970s, the evaluation of agricultural output continued to focus on the grain harvest. Despite some improvement, there were still problems such as insufficient domestic production of fodder crops and a declining sugar beet harvest. Brezhnev attempted to address these issues by increasing state investment and allowing privately owned plots to be larger. However, these actions were not effective in solving fundamental problems like a shortage of skilled workers, a ruined rural culture, and inappropriate farm machinery for small collective farms. A significant reform was necessary, but it was not supported due to ideological and political considerations.

Brezhnev’s agricultural policy reinforced the conventional methods for organizing the collective farms. Output quotas continued to be imposed centrally.[71] Khrushchev’s policy of amalgamating farms was continued by Brezhnev, because he shared Khrushchev’s belief that bigger kolkhozes would increase productivity. Brezhnev pushed for an increase in state investments in farming, which mounted to an all-time high in the 1970s of 27% of all state investment – this figure did not include investments in farm equipment. In 1981 alone, 33 billion U.S. dollars (by contemporary exchange rate) was invested into agriculture.[72]

Agricultural output in 1980 was 21% higher than the average production rate between 1966 and 1970. Cereal crop output increased by 18%. These improved results were not encouraging. In the Soviet Union the criterion for assessing agricultural output was the grain harvest. The import of cereal, which began under Khrushchev, had in fact become a normal phenomenon by Soviet standards. When Brezhnev had difficulties sealing commercial trade agreements with the United States, he went elsewhere, such as to Argentina. Trade was necessary because the Soviet Union’s domestic production of fodder crops was severely deficient. Another sector that was hitting the wall was the sugar beet harvest, which had declined by 2% in the 1970s. Brezhnev’s way of resolving these issues was to increase state investment. Politburo member Gennady Voronov advocated for the division of each farm’s work-force into what he called «links».[72] These «links» would be entrusted with specific functions, such as to run a farm’s dairy unit. His argument was that the larger the work force, the less responsible they felt.[72] This program had been proposed to Joseph Stalin by Andrey Andreyev in the 1940s, and had been opposed by Khrushchev before and after Stalin’s death. Voronov was also unsuccessful; Brezhnev turned him down, and in 1973 he was removed from the Politburo.[73]

Experimentation with «links» was not disallowed on a local basis, with Mikhail Gorbachev, the then First Secretary of the Stavropol Regional Committee, experimenting with links in his region. In the meantime, the Soviet government’s involvement in agriculture was, according to Robert Service, otherwise «unimaginative» and «incompetent».[73] Facing mounting problems with agriculture, the Politburo issued a resolution titled, «On the Further Development of Specialisation and Concentration of Agricultural Production on the Basis of Inter-Farm Co-operation and Agro-Industrial Integration».[73] The resolution ordered kolkhozes close to each other to collaborate in their efforts to increase production. In the meantime, the state’s subsidies to the food-and-agriculture sector did not prevent bankrupt farms from operating: rises in the price of produce were offset by rises in the cost of oil and other resources. By 1977, oil cost 84% more than it did in the late 1960s. The cost of other resources had also climbed by the late 1970s.[73]

Brezhnev’s answer to these problems was to issue two decrees, one in 1977 and one in 1981, which called for an increase in the maximum size of privately owned plots within the Soviet Union to half a hectare. These measures removed important obstacles for the expansion of agricultural output, but did not solve the problem. Under Brezhnev, private plots yielded 30% of the national agricultural production when they cultivated only 4% of the land. This was seen by some as proof that de-collectivization was necessary to prevent Soviet agriculture from collapsing, but leading Soviet politicians shrank from supporting such drastic measures due to ideological and political interests.[73] The underlying problems were the growing shortage of skilled workers, a wrecked rural culture, the payment of workers in proportion to the quantity rather than the quality of their work, and too large farm machinery for the small collective farms and the roadless countryside. In the face of this, Brezhnev’s only options were schemes such as large land reclamation and irrigation projects, or of course, radical reform.[74]

Society[edit]

Over the eighteen years that Brezhnev ruled the Soviet Union, average income per head increased by half; three-quarters of this growth came in the 1960s and early 1970s. During the second half of Brezhnev’s premiership, the average income per head grew by one-quarter.[75] In the first half of the Brezhnev period, income per head increased by 3.5% per annum; slightly less growth than what it had been the previous years. This can be explained by Brezhnev’s reversal of most of Khrushchev’s policies.[58] Consumption per head rose by an estimated 70% under Brezhnev, but with three-quarters of this growth happening before 1973 and only one-quarter in the second half of his rule.[76] Most of the increase in consumer production in the early Brezhnev era can be attributed to the Kosygin reform.[77]

When the USSR’s economic growth stalled in the 1970s, the standard of living and housing quality improved significantly.[78] Instead of paying more attention to the economy, the Soviet leadership under Brezhnev tried to improve the living standard in the Soviet Union by extending social benefits. This led to an increase, though a minor one, in public support.[63] The standard of living in the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR) had fallen behind that of the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic (GSSR) and the Estonian Soviet Socialist Republic (ESSR) under Brezhnev; this led many Russians to believe that the policies of the Soviet Government were hurting the Russian population.[79] The state usually moved workers from one job to another, which ultimately became an ineradicable feature in the Soviet industry.[80] Government industries such as factories, mines and offices were staffed by undisciplined personnel who put a great effort into not doing their jobs; this ultimately led, according to Robert Service, to a «work-shy workforce».[81] The Soviet Government had no effective counter-measure; it was extremely difficult, if not impossible to replace ineffective workers because of the country’s lack of unemployment.

While some areas improved during the Brezhnev era, the majority of civilian services deteriorated and living conditions for Soviet citizens fell rapidly. Diseases were on the rise[81] because of the decaying healthcare system. The living space remained rather small by First World standards, with the average Soviet person living on 13.4 square metres. Thousands of Moscow inhabitants became homeless, most of them living in shacks, doorways and parked trams. Nutrition ceased to improve in the late 1970s, while rationing of staple food products returned to Sverdlovsk for instance.[82]

The state provided recreation facilities and annual holidays for hard-working citizens. Soviet trade unions rewarded hard-working members and their families with beach vacations in Crimea and Georgia.[83]

Social rigidification became a common feature of Soviet society. During the Stalin era in the 1930s and 1940s, a common labourer could expect promotion to a white-collar job if he studied and obeyed Soviet authorities. In Brezhnev’s Soviet Union this was not the case. Holders of attractive positions clung to them as long as possible; mere incompetence was not seen as a good reason to dismiss anyone.[84] In this way, too, the Soviet society Brezhnev passed on had become static.[85]

Foreign and defense policies[edit]

Soviet–U.S. relations[edit]

During his eighteen years as Leader of the USSR, Brezhnev’s signature foreign policy innovation was the promotion of détente. While sharing some similarities with approaches pursued during the Khrushchev Thaw, Brezhnev’s policy significantly differed from Khrushchev’s precedent in two ways. The first was that it was more comprehensive and wide-ranging in its aims, and included signing agreements on arms control, crisis prevention, East–West trade, European security and human rights. The second part of the policy was based on the importance of equalizing the military strength of the United States and the Soviet Union.[according to whom?] Defense spending under Brezhnev between 1965 and 1970 increased by 40%, and annual increases continued thereafter. In the year of Brezhnev’s death in 1982, 12% of GNP was spent on the military.[86]

At the 1972 Moscow Summit, Brezhnev and U.S. President Richard Nixon signed the SALT I Treaty.[87] The first part of the agreement set limits on each side’s development of nuclear missiles.[88] The second part of the agreement, the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty, banned both countries from designing systems to intercept incoming missiles so neither the U.S. or the Soviet Union would be emboldened to strike the other without fear of nuclear retaliation.[89]

By the mid-1970s, it became clear that Henry Kissinger’s policy of détente towards the Soviet Union was failing.[according to whom?] The détente had rested on the assumption that a «linkage» of some type could be found between the two countries, with the U.S. hoping that the signing of SALT I and an increase in Soviet–U.S. trade would stop the aggressive growth of communism in the third world. This did not happen, as evidenced by Brezhnev’s continued military support for the communist guerillas fighting against the U.S. during the Vietnam War. [90]

After Gerald Ford lost the presidential election to Jimmy Carter,[91] American foreign policies became more overtly aggressive in vocabulary towards the Soviet Union and the communist world, attempts were also made to stop funding for repressive anti-communist governments and organizations the United States supported.[92] While at first standing for a decrease in all defense initiatives, the later years of Carter’s presidency would increase spending on the U.S. military.[91] When Brezhnev authorized the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979, Carter, following the advice of his National Security Adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski, denounced the intervention, describing it as the «most serious danger to peace since 1945».[92] The U.S. stopped all grain exports to the Soviet Union and boycotted the 1980 Summer Olympics held in Moscow. The Soviet Union responded by boycotting the 1984 Summer Olympics held in Los Angeles.[92]

During Brezhnev’s rule, the Soviet Union reached the peak of its political and strategic power in relation to the United States. As a result of the limits agreed to by both superpowers in the first SALT Treaty, the Soviet Union obtained parity in nuclear weapons with the United States for the first time in the Cold War.[93] Additionally, as a result of negotiations during the Helsinki Accords, Brezhnev succeeded in securing the legitimization of Soviet hegemony over Central and Eastern Europe.[94]

The Vietnam War[edit]

Under the rule of Nikita Khrushchev, the Soviet Union initially supported North Vietnam out of «fraternal solidarity». However, as the war escalated, Khrushchev urged the North Vietnamese leadership to give up the quest of liberating South Vietnam. He continued by rejecting an offer of assistance made by the North Vietnamese government, and instead told them to enter negotiations in the United Nations Security Council.[95] After Khrushchev’s ousting, Brezhnev resumed aiding the communist resistance in Vietnam. In February 1965, Premier Kosygin visited Hanoi with a dozen Soviet air force generals and economic experts.[96] Over the course of the war, Brezhnev’s regime would ultimately ship $450 million worth of arms annually to North Vietnam.[97]

Lyndon B. Johnson privately suggested to Brezhnev that he would guarantee an end to South Vietnamese hostility if Brezhnev would guarantee a North Vietnamese one. Brezhnev was interested in this offer initially, but rejected the offer upon being told by Andrei Gromyko that the North Vietnamese were not interested in a diplomatic solution to the war. The Johnson administration responded to this rejection by expanding the American presence in Vietnam, but later invited the USSR to negotiate a treaty concerning arms control. The USSR initially did not respond, because of the power struggle between Brezhnev and Kosygin over which figure had the right to represent Soviet interests abroad and later because of the escalation of the «dirty war» in Vietnam.[96]

In early 1967, Johnson offered to make a deal with Ho Chi Minh, and said he was prepared to end U.S. bombing raids in North Vietnam if Ho ended his infiltration of South Vietnam. The U.S. bombing raids halted for a few days and Kosygin publicly announced his support for this offer. The North Vietnamese government failed to respond, and because of this, the U.S. continued its raids in North Vietnam. After this event, Brezhnev concluded that seeking diplomatic solutions to the ongoing war in Vietnam was hopeless. Later in 1968, Johnson invited Kosygin to the United States to discuss ongoing problems in Vietnam and the arms race. The summit was marked by a friendly atmosphere, but there were no concrete breakthroughs by either side.[98]

In the aftermath of the Sino–Soviet border conflict, the Chinese continued to aid the North Vietnamese regime, but with the death of Ho Chi Minh in 1969, China’s strongest link to North Vietnam was gone. In the meantime, Richard Nixon had been elected President of the United States. While having been known for his anti-communist rhetoric, Nixon said in 1971 that the U.S. «must have relations with Communist China».[99] His plan was for a slow withdrawal of U.S. troops from South Vietnam, while still retaining the government of South Vietnam. The only way he thought this was possible was by improving relations with both Communist China and the USSR. He later made a visit to Moscow to negotiate a treaty on arms control and the Vietnam war, but on Vietnam nothing could be agreed.[99] Ultimately, years of Soviet military aid to North Vietnam finally bore fruit when collapsing morale among U.S. forces ultimately compelled their complete withdrawal from South Vietnam by 1973,[100][101] thereby making way for the country’s unification under communist rule two years later.

Sino–Soviet relations[edit]

Soviet foreign relations with the People’s Republic of China quickly deteriorated after Nikita Khrushchev’s attempts to reach a rapprochement with more liberal Eastern European states such as Yugoslavia and the west.[102] When Brezhnev consolidated his power base in the 1960s, China was descending into crisis because of Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution, which led to the decimation of the Chinese Communist Party and other ruling offices. Brezhnev, a pragmatic politician who promoted the idea of «stabilization», could not comprehend why Mao would start such a «self-destructive» drive to finish the socialist revolution, according to himself.[103] However, Brezhnev had problems of his own in the form of Czechoslovakia whose sharp deviation from the Soviet model prompted him and the rest of the Warsaw Pact to invade their Eastern Bloc ally. In the aftermath of the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, the Soviet leadership proclaimed the Brezhnev Doctrine that proclaimed that any threat to «socialist rule» in any state of the Soviet Bloc in Central and Eastern Europe was a threat to all of them, and therefore, it justified the intervention of fellow socialist states. It was proclaimed in order to justify the Soviet-led occupation of Czechoslovakia earlier in 1968, with the overthrow of the reformist government there. The references to «socialism» meant control by the communist parties which were loyal to the Kremlin.[104][103] This new policy increased tension not only with the Eastern Bloc, but also the Asian communist states. By 1969, relations with other communist countries had deteriorated to a level where Brezhnev was not even able to gather five of the fourteen ruling communist parties to attend an international conference in Moscow. In the aftermath of the failed conference, the Soviets concluded, «there was no leading center of the international communist movement.»[105] Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev repudiated the Brezhnev Doctrine in the late 1980s, as the Kremlin accepted the peaceful overthrow of Soviet rule in all its satellite countries in Eastern Europe.[106]

Later in 1969, the deterioration in bilateral relations culminated in the Sino–Soviet border conflict.[105] The Sino–Soviet split had chagrined Premier Alexei Kosygin a great deal, and for a while he refused to accept its irrevocability; he briefly visited Beijing in 1969 due to the increase of tension between the USSR and China.[107] By the early 1980s, both the Chinese and the Soviets were issuing statements calling for a normalization of relations between the two states. The conditions given to the Soviets by the Chinese were the reduction of Soviet military presence in the Sino–Soviet border, the withdrawal of Soviet troops in Afghanistan and the Mongolian People’s Republic; furthermore, China also wanted the Soviets to end their support for the Vietnamese invasion of Cambodia. Brezhnev responded in his March 1982 speech in Tashkent where he called for the normalization of relations. Full Sino–Soviet normalization of relations would prove to take years, until the last Soviet ruler, Mikhail Gorbachev came to power.[108]

Intervention in Afghanistan[edit]

After the communist revolution in Afghanistan in 1978, authoritarian actions forced upon the populace by the Communist regime led to the Afghan civil war, with the mujahideen leading the popular backlash against the regime.[109] The Soviet Union was worried that they were losing their influence in Central Asia, so after a KGB report claimed that Afghanistan could be taken in a matter of weeks, Brezhnev and several top party officials agreed to a full intervention.[92] Contemporary researchers tend to believe that Brezhnev had been misinformed on the situation in Afghanistan. His health had decayed, and proponents of direct military intervention took over the majority group in the Politburo by cheating and using falsified evidence. They advocated a relatively moderate scenario, maintaining a cadre of 1,500 to 2,500 Soviet military advisers and technicians in the country (which had already been there in large numbers since the 1950s),[110] but they disagreed on sending regular army units in hundreds of thousands of troops. Some believe that Brezhnev’s signature on the decree was obtained without telling him the full story, otherwise he would have never approved such a decision. Soviet ambassador to the U.S. Anatoly Dobrynin believed that the real mastermind behind the invasion, who misinformed Brezhnev, was Mikhail Suslov.[111] Brezhnev’s personal physician Mikhail Kosarev later recalled that Brezhnev, when he was in his right mind, in fact resisted the full-scale intervention.[112] Deputy Chairman of the State Duma Vladimir Zhirinovsky stated officially that despite the military solution being supported by some, hardline Defense Minister Dmitry Ustinov was the only Politburo member who insisted on sending regular army units.[113] Parts of the Soviet military establishment were opposed to any sort of active Soviet military presence in Afghanistan, believing that the Soviet Union should leave Afghan politics alone.

Invasion of Czechoslovakia[edit]

The first crisis for Brezhnev’s regime came in 1968, with the attempt by the Communist leadership in Czechoslovakia, under Alexander Dubček, to liberalize the Communist system (Prague Spring).[114] In July, Brezhnev publicly denounced the Czechoslovak leadership as «revisionist» and «anti-Soviet». Despite his hardline public statements, Brezhnev was not the one pushing hardest for the use of military force in Czechoslovakia when the issue was before the Politburo. [115]Archival evidence suggests that Brezhnev[115] was one of the few who was looking for a temporary compromise with the reform-friendly Czechoslovak government when their dispute came to a head. However, in the end, Brezhnev concluded that he would risk growing turmoil domestically and within the Eastern bloc if he abstained or voted against Soviet intervention in Czechoslovakia.[116]

As pressure mounted on him within the Soviet leadership to «re-install a revolutionary government» within Prague, Brezhnev ordered the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia, and Dubček’s removal in August. Following the Soviet intervention, he met with Czechoslovak reformer Bohumil Simon, then a member of the Politburo of the Czechoslovak Communist Party, and said, «If I had not voted for Soviet armed assistance to Czechoslovakia you would not be sitting here today, but quite possibly I wouldn’t either.»[115] However, contrary to the stabilizing effect envisioned by Moscow, the invasion served as a catalyst for further dissent in the Eastern Bloc.

The Brezhnev Doctrine[edit]

In the aftermath of the Prague Spring’s suppression, Brezhnev announced that the Soviet Union had the right to interfere in the internal affairs of its satellites to «safeguard socialism». This became known as the Brezhnev Doctrine,[117] although it was really a restatement of existing Soviet policy, as enacted by Khrushchev in Hungary in 1956. Brezhnev reiterated the doctrine in a speech at the Fifth Congress of the Polish United Workers’ Party on 13 November 1968:[114]

When forces that are hostile to socialism try to turn the development of some socialist country towards capitalism, it becomes not only a problem of the country concerned, but a common problem and concern of all socialist countries.

— Brezhnev, Speech to the Fifth Congress of the Polish United Workers’ Party in November 1968

Later in 1980, a political crisis emerged in Poland with the emergence of the Solidarity movement. By the end of October, Solidarity had 3 million members, and by December, had 9 million. In a public opinion poll organised by the Polish government, 89% of the respondents supported Solidarity.[118] With the Polish leadership split on what to do, the majority did not want to impose martial law, as suggested by Wojciech Jaruzelski. The Soviet Union and other states of the Eastern Bloc were unsure how to handle the situation, but Erich Honecker of East Germany pressed for military action. In a formal letter to Brezhnev, Honecker proposed a joint military measure to control the escalating problems in Poland. A CIA report suggested the Soviet military were mobilizing for an invasion.[119]

In 1980–81 representatives from the Eastern Bloc nations met at the Kremlin to discuss the Polish situation. Brezhnev eventually concluded on 10 December 1981 that it would be better to leave the domestic matters of Poland alone, reassuring the Polish delegates that the USSR would intervene only if asked to.[120] This effectively marked the end of the Brezhnev Doctrine. Notwithstanding the absence of a Soviet military intervention, Wojciech Jaruzelski ultimately gave in to Moscow’s demands by imposing a state of war, the Polish version of martial law, on 13 December 1981.[121]

Cult of personality[edit]

The last years of Brezhnev’s rule were marked by a growing personality cult. His love of medals (he received over 100) was well known, so in December 1966, on his 60th birthday, he was awarded the Hero of the Soviet Union. Brezhnev received the award, which came with the Order of Lenin and the Gold Star, three more times in celebration of his birthdays.[122] On his 70th birthday he was awarded the rank of Marshal of the Soviet Union, the Soviet Union’s highest military honour. After being awarded the rank, he attended an 18th Army Veterans meeting, dressed in a long coat and saying «Attention, the Marshal is coming!» He also conferred upon himself the rare Order of Victory in 1978, which was posthumously revoked in 1989 for not meeting the criteria for citation. A promotion to the rank of Generalissimus of the Soviet Union, planned for Brezhnev’s seventy-fifth birthday, was quietly shelved due to his ongoing health problems.[123]

Brezhnev’s eagerness for undeserved glory was shown by his poorly written memoirs recalling his military service during World War II, which treated the minor battles near Novorossiysk as a decisive military theatre.[74] Despite his book’s apparent weaknesses, it was awarded the Lenin Prize for Literature and was hailed by the Soviet press.[123] The book was followed by two other books, one on the Virgin Lands Campaign.[124]

Health problems[edit]

Brezhnev’s personality cult was growing at a time when his health was in rapid decline. His physical condition was deteriorating; he had been a heavy smoker until the 1970s,[125] had become addicted to sleeping pills and tranquilizers,[126] and had begun drinking to excess. His niece Lyubov Brezhneva attributed his dependencies and overall decline to severe depression caused by, in addition to the stress of his job and the general situation of the country, an extremely unhappy family life with near daily conflicts with his wife and children, in particular his troubled daughter Galina, whose erratic behavior, failed marriages and involvement in corruption took a heavy toll on Brezhnev’s mental and physical health. Brezhnev had considered divorcing his wife and disowning his children many times but intervention from his extended family and the Politburo, fearing negative publicity, managed to dissuade him. Over the years he had become overweight. From 1973 until his death, Brezhnev’s central nervous system underwent chronic deterioration and he had several minor strokes as well as insomnia. In 1975 he suffered his first heart attack.[127] When receiving the Order of Lenin, Brezhnev walked shakily and fumbled his words. According to one American intelligence expert, United States officials knew for several years that Brezhnev had suffered from severe arteriosclerosis and believed he had suffered from other unspecified ailments as well. In 1977, American intelligence officials publicly suggested that Brezhnev had also been suffering from gout, leukemia and emphysema from decades of heavy smoking,[128] as well as chronic bronchitis.[125] He was reported to have been fitted with a pacemaker to control his heart rhythm abnormalities. On occasion, he was known to have suffered from memory loss, speaking problems and had difficulties with coordination.[129] According to The Washington Post, «All of this is also reported to be taking its toll on Brezhnev’s mood. He is said to be depressed, despondent over his own failing health and discouraged by the death of many of his long-time colleagues. To help, he has turned to regular counseling and hypnosis by an Assyrian woman, a sort of modern-day Rasputin.»[125]

Upon suffering a stroke in 1975, Brezhnev’s ability to lead the Soviet Union was significantly compromised. As his ability to define Soviet foreign policy weakened, he increasingly deferred to the opinions of a hardline brain trust comprising KGB Chairman Yuri Andropov, longtime Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko, and Defense Minister Andrei Grechko (who was succeeded by Dmitriy Ustinov in 1976).[130][131]

The Ministry of Health kept doctors by Brezhnev’s side at all times, and he was brought back from near-death on several occasions. At this time, most senior officers of the CPSU wanted to keep Brezhnev alive. Even though an increasing number of officials were frustrated with his policies, no one in the regime wanted to risk a new period of domestic turmoil which might be caused by his death.[132] Western commentators started guessing who was Brezhnev’s heir apparent. The most notable candidates were Suslov and Andrei Kirilenko, who were both older than Brezhnev, and Fyodor Kulakov and Konstantin Chernenko, who were younger; Kulakov died of natural causes in 1978.[133]

Last years and death[edit]

Brezhnev’s health worsened in the winter of 1981–82. While the Politburo was pondering the question of who would succeed, all signs indicated that the ailing leader was dying. The choice of the successor would have been influenced by Suslov, but he died at the age of 79 in January 1982. Andropov took Suslov’s seat in the Central Committee Secretariat; by May, it became obvious that Andropov would make a bid for the office of the General Secretary. With the help of fellow KGB associates, he started circulating rumors that political corruption had become worse during Brezhnev’s tenure as leader, in an attempt to create an environment hostile to Brezhnev in the Politburo. Andropov’s actions showed that he was not afraid of Brezhnev’s wrath.[134]

In March 1982 Brezhnev received a concussion and fractured his right clavicle while touring a factory in Tashkent, after a metal balustrade collapsed under the weight of a number of factory workers, falling on top of Brezhnev and his security detail.[135] This incident was reported in Western media as Brezhnev having suffered a stroke.[136][137] After a month-long recovery, Brezhnev worked intermittently through November. On 7 November 1982, he was present standing on the Lenin Mausoleum’s balcony during the annual military parade and demonstration of workers commemorating the 65th anniversary of the October Revolution.[138] The event marked Brezhnev’s final public appearance before dying three days later after suffering a heart attack.[134] He was honored with a state funeral after a five-day period of nationwide mourning. He was buried in the Kremlin Wall Necropolis in Red Square,[139] in one of the twelve individual tombs located between the Lenin Mausoleum and the Kremlin wall.

National and international statesmen from around the globe attended his funeral. His wife and family were also present.[140] Brezhnev was dressed for burial in his Marshal’s uniform along with his medals.[134]

Legacy[edit]

Brezhnev presided over the Soviet Union for longer than any other person except Joseph Stalin. He is often criticised for the prolonged Era of Stagnation, in which fundamental economic problems were ignored and the Soviet political system was allowed to decline. During Mikhail Gorbachev’s tenure as leader there was an increase in criticism of the Brezhnev years, such as claims that Brezhnev followed «a fierce neo-Stalinist line». The Gorbachevian discourse blamed Brezhnev for failing to modernize the country and to change with the times,[141] although in a later statement Gorbachev made assurances that Brezhnev was not as bad as he was made out to be, saying, «Brezhnev was nothing like the cartoon figure that is made of him now.»[142] The intervention in Afghanistan, which was one of the major decisions of his career, also significantly undermined both the international standing and the internal strength of the Soviet Union.[92] In Brezhnev’s defense, it can be said that the Soviet Union reached unprecedented and never-repeated levels of power, prestige, and internal calm under his rule.[143]

Brezhnev has fared well in opinion polls when compared to his successors and predecessors in Russia. In an opinion poll by VTsIOM in 2007 the majority of Russians chose to live during the Brezhnev era rather than any other period of 20th century Soviet history.[144] In a Levada Center poll conducted in 2013, Brezhnev beat Vladimir Lenin as Russia’s favorite leader in the 20th century with 56% approval.[145] In another poll in 2013, Brezhnev was voted the best Russian leader of the 20th century.[146] In a 2018 Rating Sociological Group poll, 47% of Ukrainian respondents had a positive opinion of Brezhnev.[147]

In the West he is most commonly remembered for starting the economic stagnation that triggered the dissolution of the Soviet Union.[148]

Personality traits[edit]

Russian historian Roy Medvedev emphasizes the bureaucratic mentality and personality strengths that enabled Brezhnev to gain power. He was loyal to his friends, vain in desiring ceremonial power, and refused to control corruption inside the party. Especially in foreign affairs, Brezhnev increasingly took all major decisions into his own hands, without telling his colleagues in the Politburo.[149] He deliberately presented a different persona to different people, culminating in the systematic glorification of his own career.[150]

Brezhnev’s vanity made him the target of many political jokes.[123] Nikolai Podgorny warned him of this, but Brezhnev replied, «If they are poking fun at me, it means they like me.»[151]

In keeping with traditional socialist greetings, Brezhnev kissed many politicians on the lips during his career. One of these occasions, with Erich Honecker, was the subject of My God, Help Me to Survive This Deadly Love, a mural painted on the Berlin Wall after its opening and dismantlement.[152][153][154][155]

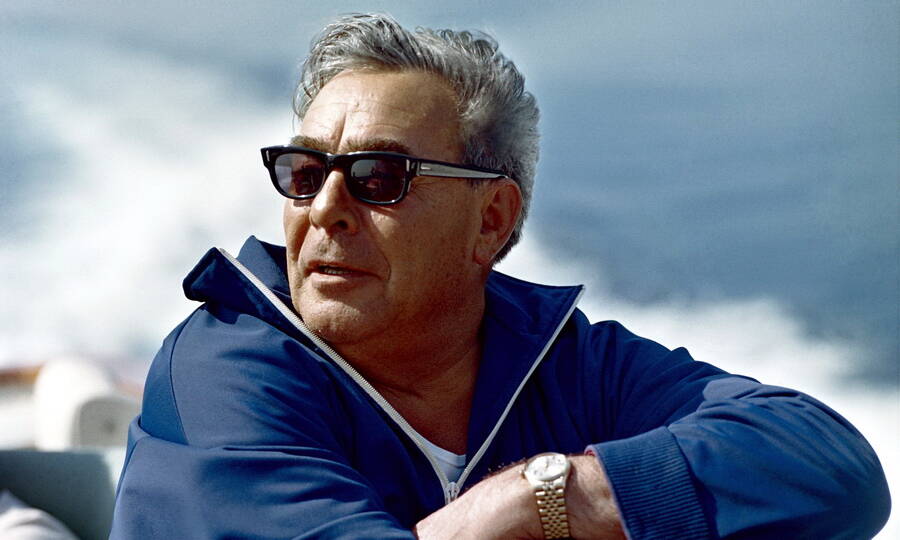

Brezhnev’s main passion was driving foreign cars given to him by leaders of state from across the world. He usually drove these between his dacha and the Kremlin with, according to historian Robert Service, flagrant disregard for public safety.[156] When visiting the United States for a summit with Nixon in 1973, he expressed a wish to drive around Washington in a Lincoln Continental that Nixon had just given him; upon being told that the Secret Service would not allow him to do this, he said «I will take the flag off the car, put on dark glasses, so they can’t see my eyebrows and drive like any American would» to which Henry Kissinger replied «I have driven with you and I don’t think you drive like an American!»[157]

Personal life[edit]

Brezhnev was married to Viktoria Denisova (1908–1995). He had a daughter, Galina,[156] and a son, Yuri.[158] His niece Lyubov Brezhneva published a memoir in 1995 which claimed that Brezhnev worked systematically to bring privileges to his family in terms of appointments, apartments, private luxury stores, private medical facilities and immunity from prosecution.[159]

Honours[edit]

Brezhnev received several accolades and honours from his home country and foreign countries. Among his foreign honours are the Bangladesh Liberation War Honour (Bangladesh Muktijuddho Sanmanona) and the Hero of the Mongolian People’s Republic.

See also[edit]

- Attempted assassination of Leonid Brezhnev

- Bibliography of the Post Stalinist Soviet Union

- Neo-Stalinism

Explanatory notes[edit]

- ^ Western specialists believe that the net material product (NMP; Soviet version of gross national product [GNP]) contained distortions and could not accurately determine a country’s economic growth; according to some, it greatly exaggerated growth. Because of this, several specialists created GNP figures to estimate Soviet growth rates and to compare Soviet growth rates with the growth rates of capitalist countries.[45] Grigorii Khanin published his growth rates in the 1980s as a «translation» of NMP to GNP. His growth rates were (as seen above) much lower than the official figures, and lower than some Western estimates. His estimates were widely publicized by conservative think tanks as, for instance, The Heritage Foundation of Washington, D.C. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, Khanin’s estimates led several agencies to criticize the estimates made by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). Since then the CIA has often been accused over overestimating Soviet growth. In response to the criticism of CIA’s work, a panel led by economist James R. Millar was established to check out if this was in fact true. The panel concluded that the CIA were based on facts, and that «Methodologically, Khanin’s approach was naive, and it has not been possible for others to reproduce his results.»[46] Michael Boretsky, a Department of Commerce economist, criticized the CIA estimates to be too low. He used the same CIA methodology to estimate West German and American growth rates. The results were 32% below the official GNP growth for West Germany, and 13 below the official GNP growth for the United States. In the end, the conclusion is the same, the Soviet Union grew rapidly economically until the mid-1970s, when a systematic crisis began.[47]

- Growth figures for the Soviet economy varies widely (as seen below):

- Eighth Five-Year Plan (1966–1970)

- Gross national product (GNP): 5.2% [48] or 5.3% [49]

- Gross national income (GNI): 7.1% [50]

- Capital investments in agriculture: 24% [51]

- Ninth Five-Year Plan (1971–1975)

- GNP: 3.7% [48]

- GNI: 5.1% [50]

- Labour productivity: 6% [52]

- Capital investments in agriculture: 27% [51]

- Tenth Five-Year Plan (1976–1980)

- GNP: 2.7% [48]

- GNP: 3% [49]

- Labour productivity: 3.2% [52]

- Eleventh Five-Year Plan (1981–1985)

- ^ As First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 14 October 1964 to 8 April 1966. The office was renamed back to General Secretary at the 23rd Party Congress,[1] which had been its name from 1922 to 1952.[2]

- ^ Russian: Леонид Ильич Брежнев, IPA: [lʲɪɐˈnʲit ɨˈlʲjidʑ ˈbrʲeʐnʲɪf] ⓘ;[3] Ukrainian: Леонід Ілліч Брежнєв, IPA: [leoˈn⁽ʲ⁾id iˈl⁽ʲ⁾ːidʒ ˈbrɛʒnʲeu̯].

Citations[edit]

- ^ McCauley, Martin (1997), Who’s who in Russia since 1900 p. 48. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-13898-1.

- ^ Brown, Archie (2009). The Rise & Fall of Communism, p. 59. Bodley Head. ISBN 978-0061138799.

- ^ «Brezhnev». Random House Webster’s Unabridged Dictionary.

- ^ Jessup, John E. (11 August 1998). An Encyclopedic Dictionary of Conflict and Conflict Resolution, 1945–1996. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-313-28112-9.

- ^ «Wikimedia commons: L.I. Brezhnev military card».

- ^ «File:Brezhnev LI OrKrZn NagrList 1942.jpg».

- ^ «File:Brezhnev LI Pasport 1947.jpg». 11 June 1947.

- ^ Brezhnev LI OrOtVo NagrList 1943.jpg (image). 18 September 1943 – via Wikimedia Commons.

- ^ a b c Bacon 2002, p. 6.

- ^ «ЖИЗНЬ ПО ЗАВОДСКОМУ ГУДКУ». supol.narod.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 12 June 2022.

- ^ a b McCauley 1997, p. 47.

- ^ a b Green & Reeves 1993, p. 192.

- ^ Murphy 1981, p. 80.

- ^ Childs 2000, p. 84.

- ^ a b McCauley 1997, p. 48.

- ^ Bacon 2002, p. 7.

- ^ Hough, Jerry F. (November 1982). «Soviet succession and policy choices». Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. p. 49. Retrieved 11 May 2010.

- ^ Hough & Fainsod 1979, p. 371.

- ^ Taubman 2003, p. 615.

- ^ Taubman 2003, p. 616.

- ^ Service 2009, p. 376.

- ^ a b Service 2009, p. 377.

- ^ Taubman 2003, p. 5.

- ^ a b c Service 2009, p. 378.

- ^ McNeal 1975, p. 164.

- ^ Taubman 2003, p. 16.

- ^ George W. Breslauer, Khrushchev and Brezhnev As Leaders (1982).

- ^ Bacon 2002, p. 32 «In the mid-1960s appraisals of Brezhnev centered on the new leadership of the Soviet Union as a whole. Just as in the early Khrushchev years, it was not immediately apparent after 1964 who wielded how much power in the Soviet hierarchy. The immediate talk was of a triumvirate of Brezhnev at the head of the Communist Party, Kosygin as prime minister (Chairman of the Presidium of the Council of Ministers), and ― after December 1965 ― Podgorny as Chairman of the Supreme Soviet.»

- ^ Daniels 1998, p. 36 «Podgorny, a longtime member of the [party] apparatus, joined the Secretariat in 1963 with Brezhnev, which made him also figure as a candidate for supreme power. At first number-three in the post-Khrushchev troika, along with the new Secretary-General Brezhnev and Prime Minister Kosygin, Podgorny rose more recently to the number-two position in Communist protocol, after Brezhnev but ahead of Kosygin. Overall, this history indicates that the post of President of the Republic, long a merely honorary one, ha[d] acquired growing importance and influence in the Communist hierarchy.»

- ^ Service 2003, p. 379.

- ^ Roeder 1993, p. 110.

- ^ Roeder 1993, pp. 79–80.

- ^ Willerton 1992, p. 68 «Podgorny’s Khar’kov network was among the largest of the Brezhnev period. Its size reflected both Podgorny’s important role in Ukraine during the 1950s and early 1960s as well as his status as Brezhnev’s main political rival. Podgorny developed this network not only while he was moving up in the Ukrainian party apparatus, but also during his career as Ukrainian party boss (1957 to 1963)…An investigation of the Khar’kov party organization and publication of a CPSU [Central Committee] declaration on its deficiencies in 1965 severely weakened this elite cohort. Highly placed protégés only moved downward during the Brezhnev period. [Vitaly] Titov, who had headed the Party Organs Department and had been promoted as a party Secretary in 1962, was quickly demoted in 1965 from the CPSU Secretariat and transferred to head the troubled Kazakh party organization. Podgorny’s successor in Ukraine, Piotr Shelest, was ultimately ousted in favor of Brezhnev’s longtime protégé, Shcherbitsky. Shelest’s position in the all-union party hierarchy was never an especially important one, although his position had merited a brief membership in the Politburo. [¶]Those Podgorny associates who became CC members had moved up from Khar’kov and Kiev in the 1940s, 1950s, and early 1960s. Some advanced to Moscow with Podgorny…Nearly all were ‘retired’ either when Shelest was ousted or when Podgorny was removed in 1977.»

- ^ Brown 2009, p. 403 «[In 1965] Podgorny took Mikoyan’s place as Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet, combining that with his Politburo membership. He held both offices until Brezhnev felt strong enough unceremoniously to remove him in 1977. By then Brezhnev decided he had waited long enough to add the dignity of becoming formal head of state to his party leadership.»

- ^ Guerrier 2020, p. 1314 «In 1977 Brezhnev engineered Podgorny’s removal from the Politburo and then from the chairmanship of the Supreme Soviet on June 16. Brezhnev assumed the chairmanship himself while remaining first secretary, thus gaining diplomatic status as head of state while also maintaining the real power that came as leader of the CPSU.»

- ^ a b Brown 2009, p. 403.

- ^ Bacon 2002, pp. 13–14 «By the end of the [1960s], T.H. Rigby argued that a stable oligarchic system had developed in the Soviet Union, centered around Brezhnev, Podgorny, and Kosygin[;] plus Central Committee secretaries Mikhail Suslov and Andrei Kirilenko. Accurate though this assessment was at the time, its publication coincided with the further strengthening of Brezhnev’s position by means of an apparent clash with Suslov. [¶] At a Central Committee plenum in December 1969, Brezhnev gave a frank speech on economic matters, which had not been agreed with other Politburo members in advance. This independent line both surprised and angered colleagues, particularly Suslov, Shelepin, and first deputy prime minister Kiril Mazurov, who wrote a joint letter critical of the speech which they intended to be discussed at the next Plenum in March 1970. Brezhnev, however, exerted pressure on Suslov and his colleagues, the Plenum was postponed, the letter withdrawn, and the General Secretary emerged with greater authority and pledges of authority from his erstwhile critics.»

- ^ Bacon 2002, p. 10.

- ^ Willerton 1992, pp. 62–63 «The Brezhnev network constituted a broad coalition of politicians and interests which was in an organizational position to structure the [Soviet] policy agenda. Trusted subordinates guided those state organizations critical to the realization of the Brezhnev program. Meanwhile, members of this network linked a number of important regional party organizations, both within the RSFSR and outside it, to the regime in Moscow…In general, network members headed the [Central Committee] departments responsible for cadres, party work, and important sectors of the economy. By the mid-1970s, the Politburo members and CPSU secretaries supervising these departments were all Brezhnev protégés. From an organizational standpoint, the Brezhnev-led network of patronage factions was the dominant element in the [Soviet] national leadership…»

- ^ Service 2009, p. 380.

- ^ a b Service 2009, p. 381.

- ^ a b Sakwa 1999, p. 339.

- ^ a b Service 2009, p. 382.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Bacon & Sandle 2002, p. 40.

- ^ Kotz & Weir 2007, p. 35.

- ^ Kotz & Weir 2007, p. 39.

- ^ Kotz & Weir 2007, p. 40.

- ^ a b c Kort 2010, p. 322.

- ^ a b Bergson 1985, p. 192.

- ^ a b Pallot & Shaw 1981, p. 51.

- ^ a b Wegren 1998, p. 252.

- ^ a b Arnot 1988, p. 67.

- ^ Service 2009, p. 385.

- ^ Service 2009, p. 386.

- ^ Service 2009, p. 389.

- ^ Service 2009, p. 407.

- ^ Service 2009, p. 397.

- ^ a b Bacon & Sandle 2002, p. 47.

- ^ Richard W. Judy; Robert W. Clough (1989). in Marshall C. Yovits, ed. «Advances in Computers» vol. 29. Academic Press. p. 252. ISBN 9780080566610.

- ^ William J. Tompson (2014). The Soviet Union under Brezhnev. Routledge. pp. 78–82. ISBN 9781317881728.

- ^ Bacon & Sandle 2002, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Sakwa 1999, p. 341.

- ^ a b Bacon & Sandle 2002, p. 28.

- ^ a b Oliver & Aldcroft 2007, p. 275.

- ^ Shane, Scott (1994). «What Price Socialism? An Economy Without Information». Dismantling Utopia: How Information Ended the Soviet Union. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee. pp. 75 to 98. ISBN 978-1-56663-048-1.

It was not the gas pedal but the steering wheel that was failing

- ^ a b Ter-Ghazaryan, Aram (24 September 2014). «Computers in the USSR: A story of missed opportunities». Russia Beyond the Headlines. Archived from the original on 23 October 2017. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

- ^ James W. Cortada, «Public Policies and the Development of National Computer Industries in Britain, France, and the Soviet Union, 1940—80.» Journal of Contemporary History (2009) 44#3 pp: 493–512, especially page 509-10.

- ^ Frank Cain, «Computers and the Cold War: United States restrictions on the export of computers to the Soviet Union and Communist China.» Journal of Contemporary History (2005) 40#1 pp: 131–147. in JSTOR

- ^ Andrey Kolesnikov (17 December 2010). «30 лет назад умер Алексей Косыгин» [A reformer before Yegor Gaidar? Kosygin died for 30 years ago]. Forbes Russia (in Russian). Retrieved 29 December 2010.

- ^ Oliver & Aldcroft 2007, p. 276.

- ^ Service 2009, p. 400.

- ^ a b c Service 2009, p. 401.

- ^ a b c d e Service 2009, p. 402.

- ^ a b Service 2009, p. 403.

- ^ Bacon & Sandle 2002, p. 45.

- ^ Bacon & Sandle 2002, p. 48.

- ^ Анализ динамики показателей уровня жизни населения (in Russian). Moscow State University. Retrieved 5 October 2010.

- ^ Sakwa 1998, p. 28.

- ^ Service 2009, p. 423.

- ^ Service 2009, p. 416.

- ^ a b Service 2009, p. 417.

- ^ Service 2009, p. 418.

- ^ Service 2009, p. 421.

- ^ Service 2009, p. 422.

- ^ Service 2009, p. 427.

- ^ Bacon & Sandle 2002, p. 90.

- ^ «SALT 1». Department of State. Retrieved 11 April 2010.

- ^ Axelrod, Alan (2009). The Real History of the Cold War A New Look at the Past. Sterling Publishing Co., Inc. p. 380. ISBN 978-1-4027-6302-1.

- ^ Foner, Eric (1 February 2012). Give Me Liberty!: An American History (3 ed.). W. W. Norton & Company. p. 815. ISBN 978-0393935530.

- ^ McCauley 2008, p. 75.

- ^ a b McCauley 2008, p. 76.

- ^ a b c d e McCauley 2008, p. 77.

- ^ «The President». Richard Nixon Presidential Library. Archived from the original on 27 August 2009. Retrieved 11 May 2010.

- ^ Hiden, Made & Smith 2008, p. 209.

- ^ Loth 2002, pp. 85–86.

- ^ a b Loth 2002, p. 86.