А

Автухова Татьяна Анатольевна (Витебский-Чкаловский округ № 18)

член Постоянной комиссии по образованию, культуре и науке

Адаменко Евгений Буниславович (Калинковичский округ № 41)

член Постоянной комиссии по жилищной политике и строительству

Азаренко Владимир Николаевич (Кричевский округ № 83)

заместитель председателя Постоянной комиссии по вопросам экологии, природопользования и чернобыльской катастрофы

Ананич Лилия Станиславовна (Борисовский сельский округ № 63)

заместитель председателя Постоянной комиссии по правам человека, национальным отношениям и средствам массовой информации

Андрейченко Владимир Павлович (Докшицкий округ № 22)

Председатель Палаты представителей

Аутко Александр Викторович (Гродненский сельский округ № 53)

заместитель председателя Постоянной комиссии по аграрной политике

Б

Бартош Светлана Владимировна (Днепро-Бугский округ № 10)

член Постоянной комиссии по бюджету и финансам

Бегеба Валентина Константиновна (Пинский сельский округ № 15)

заместитель председателя Постоянной комиссии по вопросам экологии, природопользования и чернобыльской катастрофы

Белоконев Олег Алексеевич (Пуховичский округ № 65)

председатель Постоянной комиссии по национальной безопасности

Боболович Александр Сергеевич (Столинский округ № 16)

заместитель председателя Постоянной комиссии по жилищной политике и строительству

Брич Леонид Григорьевич (Брестский-Западный округ № 1)

председатель Постоянной комиссии по экономической политике

В

Вабищевич Петр Андреевич (Логойский округ № 75)

заместитель председателя Постоянной комиссии по бюджету и финансам

Василевич Мария Викторовна (Кальварийский округ № 104)

член Постоянной комиссии по правам человека, национальным отношениям и средствам массовой информации

Васильков Николай Андреевич (Буда-Кошелевский округ № 38)

председатель Постоянной комиссии по вопросам экологии, природопользования и чернобыльской катастрофы

Васько Марина Викторовна (Брестский-Центральный округ № 2)

член Постоянной комиссии по образованию, культуре и науке

Васюков Виталий Михайлович (Оршанский-Днепровский округ № 26)

заместитель председателя Постоянной комиссии по бюджету и финансам

Волков Игорь Владимирович (Жлобинский округ № 40)

заместитель председателя Постоянной комиссии по государственному строительству, местному самоуправлению и регламенту

Воронецкий Валерий Иосифович (Свислочский округ № 94)

член Постоянной комиссии по международным делам

Г

Гайдук Оксана Вячеславовна (Есенинский округ № 100)

заместитель председателя Постоянной комиссии по жилищной политике и строительству

Гайдукевич Олег Сергеевич (Калиновский округ № 108)

заместитель председателя Постоянной комиссии по международным делам

Ганчук Андрей Александрович (Шкловский округ № 90)

член Постоянной комиссии по государственному строительству, местному самоуправлению и регламенту

Гацко Владимир Владимирович (Бобруйский сельский округ № 80)

член Постоянной комиссии по здравоохранению, физической культуре, семейной и молодежной политике

Голуб Наталья Григорьевна (Ивацевичский округ № 11)

член Постоянной комиссии по бюджету и финансам

Горваль Светлана Александровна (Витебский-Железнодорожный округ № 19)

член Постоянной комиссии по экономической политике

Гордейчик Иван Аркадьевич (Уручский округ № 109)

заместитель председателя Постоянной комиссии по труду и социальным вопросам

Гранковский Александр Александрович (Автозаводской округ № 92)

заместитель председателя Постоянной комиссии по промышленности, топливно-энергетическому комплексу, транспорту и связи

Д

Давыдько Геннадий Брониславович (Восточный округ № 107)

председатель Постоянной комиссии по правам человека, национальным отношениям и средствам массовой информации

Данченко Александр Михайлович (Гомельский-Сельмашевский округ № 32)

член Постоянной комиссии по национальной безопасности

Дашко Анатолий Михайлович (Брестский-Восточный округ № 3)

член Постоянной комиссии по труду и социальным вопросам

Демидович Василий Николаевич (Кобринский округ № 12)

заместитель председателя Постоянной комиссии по жилищной политике и строительству

Дик Сергей Константинович (Коласовский округ № 106)

член Постоянной комиссии по международным делам

Довгало Ирина Викторовна (Гомельский-Советский округ № 34)

член Постоянной комиссии по законодательству

Долгошей Тамара Сергеевна (Гродненский-Ленинский округ № 52)

член Постоянной комиссии по вопросам экологии, природопользования и чернобыльской катастрофы

Дубов Александр Васильевич (Сенненский округ № 30)

заместитель председателя Постоянной комиссии по национальной безопасности

Думбадзе Тенгиз Шукриевич (Партизанский округ № 110)

заместитель председателя Постоянной комиссии по международным делам

Е

Егоров Алексей Владимирович (Витебский-Октябрьский округ № 20)

член Постоянной комиссии по законодательству

Ж

Жолнерчик Людмила Николаевна (Барановичский сельский округ № 7)

заместитель председателя Постоянной комиссии по законодательству

З

Завалей Игорь Владимирович (Гомельский сельский округ № 37)

член Постоянной комиссии по здравоохранению, физической культуре, семейной и молодежной политике

Зайцев Евгений Станиславович (Брестский-Пограничный округ № 4)

член Постоянной комиссии по национальной безопасности

Здорикова Людмила Евгеньевна (Могилевский-Центральный округ № 85)

член Постоянной комиссии по правам человека, национальным отношениям и средствам массовой информации

Злотников Андрей Анатольевич (Гомельский-Центральный округ № 33)

Срок полномочий:

06.12.2019

— 07.03.2023

член Постоянной комиссии по образованию, культуре и науке

К

Кананович Людмила Николаевна (Молодечненский городской округ № 72)

председатель Постоянной комиссии по труду и социальным вопросам

Карась Денис Николаевич (Новополоцкий округ № 24)

член Постоянной комиссии по промышленности, топливно-энергетическому комплексу, транспорту и связи

Кирьяк Лилия Вацлавовна (Гродненский-Центральный округ № 51)

заместитель председателя Постоянной комиссии по образованию, культуре и науке

Клишевич Сергей Михайлович (Октябрьский округ № 97)

член Постоянной комиссии по образованию, культуре и науке

Колеснёва Елена Петровна (Горецкий округ № 82)

заместитель председателя Постоянной комиссии по образованию, культуре и науке

Комаровский Игорь Сергеевич (Юго-Западный округ № 99)

председатель Постоянной комиссии по промышленности, топливно-энергетическому комплексу, транспорту и связи

Кравцов Сергей Владимирович (Рогачевский округ № 45)

заместитель председателя Постоянной комиссии по аграрной политике

Кралевич Ирина Николаевна (Житковичский округ № 39)

член Постоянной комиссии по вопросам экологии, природопользования и чернобыльской катастрофы

Крачек Инна Юрьевна (Оршанский городской округ № 25)

член Постоянной комиссии по труду и социальным вопросам

Креч Ольга Зеноновна (Гомельский-Новобелицкий округ № 36)

член Постоянной комиссии по законодательству

Курсевич Валентина Вацлавовна (Заславский округ № 77)

член Постоянной комиссии по здравоохранению, физической культуре, семейной и молодежной политике

Л

Лавриненко Игорь Владимирович (Березинский округ № 61)

Срок полномочий:

06.12.2019

— 14.05.2021

заместитель председателя Постоянной комиссии по национальной безопасности

Лагунова Галина Николаевна (Шабановский округ № 91)

заместитель председателя Постоянной комиссии по экономической политике

Левчук Александр Георгиевич (Пружанский округ № 9)

член Постоянной комиссии по аграрной политике

Ленчевская Марина Александровна (Западный округ № 102)

член Постоянной комиссии по национальной безопасности

Луканская Ирина Эдуардовна (Гродненский-Занеманский округ № 49)

член Постоянной комиссии по законодательству

Любецкая Светлана Анатольевна (Старовиленский округ № 105)

председатель Постоянной комиссии по законодательству

М

Макарина-Кибак Людмила Эдуардовна (Грушевский округ № 98)

председатель Постоянной комиссии по здравоохранению, физической культуре, семейной и молодежной политике

Мамайко Иван Андреевич (Столбцовский округ № 70)

член Постоянной комиссии по национальной безопасности

Марзалюк Игорь Александрович (Могилевский-Ленинский округ № 84)

председатель Постоянной комиссии по образованию, культуре и науке

Маркевич Александр Иванович (Ивьевский округ № 54)

заместитель председателя Постоянной комиссии по национальной безопасности

Мартынов Игорь Феликсович (Лепельский округ № 23)

заместитель председателя Постоянной комиссии по национальной безопасности

Масейков Александр Анатольевич (Могилевский-Промышленный округ № 87)

заместитель председателя Постоянной комиссии по здравоохранению, физической культуре, семейной и молодежной политике

Машкаров Александр Валерьевич (Гомельский-Промышленный округ № 35)

член Постоянной комиссии по экономической политике

Михалюк Павел Рышардович (Щучинский округ № 60)

член Постоянной комиссии по здравоохранению, физической культуре, семейной и молодежной политике

Мицкевич Валерий Вацлавович (Лидский округ № 55)

заместитель Председателя Палаты представителей

Мурина Юлия Георгиевна (Солигорский сельский округ № 69)

заместитель председателя Постоянной комиссии по бюджету и финансам

Н

Назаренко Валентина Алексеевна (Мозырский округ № 42)

заместитель председателя Постоянной комиссии по международным делам

Насеня Анатолий Васильевич (Лунинецкий округ № 13)

член Постоянной комиссии по экономической политике

Нижевич Людмила Ивановна (Копыльский округ № 66)

председатель Постоянной комиссии по бюджету и финансам

Николайкин Виктор Павлович (Витебский-Горьковский округ № 17)

председатель Постоянной комиссии по жилищной политике и строительству

О

Одинцова Светлана Владимировна (Полоцкий городской округ № 27)

член Постоянной комиссии по здравоохранению, физической культуре, семейной и молодежной политике

Омельянюк Александр Павлович (Пинский городской округ № 14)

заместитель председателя Постоянной комиссии по законодательству

П

Панасюк Василий Васильевич (Пушкинский округ № 103)

заместитель председателя Постоянной комиссии по промышленности, топливно-энергетическому комплексу, транспорту и связи

Петрашова Ольга Владимировна (Могилевский-Октябрьский округ № 86)

член Постоянной комиссии по международным делам

Писаник Леонид Федорович (Полесский округ № 43)

Срок полномочий:

06.12.2019

— 05.10.2020

член Постоянной комиссии по вопросам экологии, природопользования и чернобыльской катастрофы

Подлужная Людмила Брониславовна (Сеницкий округ № 76)

член Постоянной комиссии по образованию, культуре и науке

Поконечный Павел Леонидович (Волковысский округ № 48)

член Постоянной комиссии по вопросам экологии, природопользования и чернобыльской катастрофы

Полякова Ирина Михайловна (Городокский округ № 21)

член Постоянной комиссии по аграрной политике

Попко Павел Иванович (Барановичский-Восточный округ № 6)

член Постоянной комиссии по международным делам

Потапова Елена Станиславовна (Гродненский-Октябрьский округ № 50)

член Постоянной комиссии по государственному строительству, местному самоуправлению и регламенту

Р

Ражанец Валентина Витальевна (Слуцкий округ № 67)

заместитель председателя Постоянной комиссии по правам человека, национальным отношениям и средствам массовой информации

Рынейская Ирина Николаевна (Бобруйский- Ленинский округ № 78)

заместитель председателя Постоянной комиссии по образованию, культуре и науке

С

Савиных Андрей Владимирович (Чкаловский округ № 96)

председатель Постоянной комиссии по международным делам

Сайганова Татьяна Ивановна (Купаловский округ № 95)

заместитель председателя Постоянной комиссии по экономической политике

Саракач Александр Иванович (Дзержинский округ № 71)

заместитель председателя Постоянной комиссии по промышленности, топливно-энергетическому комплексу, транспорту и связи

Свилло Виктор Збигневич (Сморгонский округ № 59)

заместитель председателя Постоянной комиссии по государственному строительству, местному самоуправлению и регламенту

Семенчук Олег Алексеевич (Молодечненский сельский округ № 73)

заместитель председателя Постоянной комиссии по труду и социальным вопросам

Семеняко Валентин Михайлович (Слонимский округ № 58)

председатель Постоянной комиссии по государственному строительству, местному самоуправлению и регламенту

Сильчёнок Павел Матвеевич (Поставский округ № 29)

член Постоянной комиссии по труду и социальным вопросам

Синяк Владимир Александрович (Неманский округ № 56)

член Постоянной комиссии по промышленности, топливно-энергетическому комплексу, транспорту и связи

Сонгин Александр Генрихович (Замковый округ № 57)

член Постоянной комиссии по законодательству

Старовойтова Анна Валентиновна (Каменногорский округ № 101)

член Постоянной комиссии по международным делам

Стативко Жанна Владимировна (Беловежский округ № 8)

заместитель председателя Постоянной комиссии по труду и социальным вопросам

Стельмашок Сергей Петрович (Речицкий округ № 44)

член Постоянной комиссии по бюджету и финансам

Стрельченок Валерий Иванович (Жодинский округ № 64)

член Постоянной комиссии по труду и социальным вопросам

Струневский Андрей Николаевич (Солигорский городской округ № 68)

член Постоянной комиссии по промышленности, топливно-энергетическому комплексу, транспорту и связи

Супранович Ирина Александровна (Вилейский округ № 74)

член Постоянной комиссии по труду и социальным вопросам

Сыранков Сергей Александрович (Быховский округ № 81)

член Постоянной комиссии по международным делам

Т

Тавтын Игорь Павлович (Светлогорский округ № 46)

член Постоянной комиссии по здравоохранению, физической культуре, семейной и молодежной политике

Тарасенко Наталья Эдуардовна (Могилевский сельский округ № 88)

член Постоянной комиссии по правам человека, национальным отношениям и средствам массовой информации

У

Уткин Виталий Юрьевич (Гомельский-Юбилейный округ № 31)

член Постоянной комиссии по законодательству

Х

Хлобукин Игорь Константинович (Барановичский-Западный округ № 5)

член Постоянной комиссии по вопросам экологии, природопользования и чернобыльской катастрофы

Ч

Чернявская Жанна Николаевна (Хойникский округ № 47)

заместитель председателя Постоянной комиссии по вопросам экологии, природопользования и чернобыльской катастрофы

Ш

Шевчук Николай Николаевич (Полоцкий сельский округ № 28)

председатель Постоянной комиссии по аграрной политике

Шипуло Александр Валерьевич (Борисовский городской округ № 62)

заместитель председателя Постоянной комиссии по здравоохранению, физической культуре, семейной и молодежной политике

Широкая Вера Владимировна (Бобруйский-Первомайский округ № 79)

член Постоянной комиссии по жилищной политике и строительству

Шкроб Марина Александровна (Васнецовский округ № 93)

заместитель председателя Постоянной комиссии по здравоохранению, физической культуре, семейной и молодежной политике

Шутова Светлана Александровна (Осиповичскиий округ № 89)

член Постоянной комиссии по государственному строительству, местному самоуправлению и регламенту

«House of Representatives committee» redirects here. For others, see Committee.

|

United States House of Representatives |

|

|---|---|

| 118th United States Congress | |

Seal of the House |

|

Flag of the United States House of Representatives |

|

| Type | |

| Type |

Lower house of the United States Congress |

|

Term limits |

None |

| History | |

|

New session started |

January 3, 2023 |

| Leadership | |

|

Speaker |

Kevin McCarthy (R) |

|

Majority Leader |

Steve Scalise (R) |

|

Minority Leader |

Hakeem Jeffries (D) |

|

Majority Whip |

Tom Emmer (R) |

|

Minority Whip |

Katherine Clark (D) |

| Structure | |

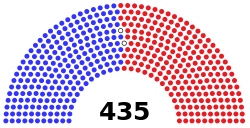

| Seats | 435 voting members 6 non-voting members 218 for a majority |

|

|

|

Political groups |

Majority (221)

Minority (212)

Vacant (2)

|

|

Length of term |

2 years |

| Elections | |

|

Voting system |

Plurality voting in 46 states[a]

Varies in 4 states

|

|

Last election |

November 8, 2022 |

|

Next election |

November 5, 2024 |

| Redistricting | State legislatures or redistricting commissions, varies by state |

| Meeting place | |

|

|

| House of Representatives Chamber United States Capitol Washington, D.C. United States of America |

|

| Website | |

| www |

|

| Rules | |

| Rules of the House of Representatives |

The United States House of Representatives is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together, they comprise the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The House’s composition was established by Article One of the United States Constitution. The House is composed of representatives who, pursuant to the Uniform Congressional District Act, sit in single member congressional districts allocated to each state on the basis of population as measured by the United States census, with each district having one representative, provided that each state is entitled to at least one. Since its inception in 1789, all representatives have been directly elected, although universal suffrage did not come to effect until after the passage of the 19th Amendment and the Civil Rights Movement. Since 1913, the number of voting representatives has been at 435 pursuant to the Apportionment Act of 1911.[1] The Reapportionment Act of 1929 capped the size of the House at 435. However, the number was temporarily increased in 1959 until 1963 to 437 when Alaska and Hawaii were admitted to the Union.[2]

In addition, five non-voting delegates represent the District of Columbia and the U.S. territories of Guam, the U.S. Virgin Islands, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, and American Samoa. A non-voting Resident Commissioner, serving a four-year term, represents the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico. As of the 2020 census, the largest delegation was California, with 52 representatives. Six states have only one representative: Alaska, Delaware, North Dakota, South Dakota, Vermont, and Wyoming.[3]

The House is charged with the passage of federal legislation, known as bills; those that are also passed by the Senate are sent to the president for consideration. The House also has exclusive powers: it initiates all revenue bills, impeaches federal officers, and elects the president if no candidate receives a majority of votes in the Electoral College.[4][5]

The House meets in the south wing of the United States Capitol. The presiding officer is the Speaker of the House, who is elected by the members thereof. Other floor leaders are chosen by the Democratic Caucus or the Republican Conference, depending on whichever party has more voting members.

History

Under the Articles of Confederation, the Congress of the Confederation was a unicameral body with equal representation for each state, any of which could veto most actions. After eight years of a more limited confederal government under the Articles, numerous political leaders such as James Madison and Alexander Hamilton initiated the Constitutional Convention in 1787, which received the Confederation Congress’s sanction to «amend the Articles of Confederation». All states except Rhode Island agreed to send delegates.

Congress’s structure was a contentious issue among the founders during the convention. Edmund Randolph’s Virginia Plan called for a bicameral Congress: the lower house would be «of the people», elected directly by the people of the United States and representing public opinion, and a more deliberative upper house, elected by the lower house, that would represent the individual states, and would be less susceptible to variations of mass sentiment.[7]

The House is commonly referred to as the lower house and the Senate the upper house, although the United States Constitution does not use that terminology. Both houses’ approval is necessary for the passage of legislation. The Virginia Plan drew the support of delegates from large states such as Virginia, Massachusetts, and Pennsylvania, as it called for representation based on population. The smaller states, however, favored the New Jersey Plan, which called for a unicameral Congress with equal representation for the states.[7]

Eventually, the Convention reached the Connecticut Compromise or Great Compromise, under which one house of Congress (the House of Representatives) would provide representation proportional to each state’s population, whereas the other (the Senate) would provide equal representation amongst the states.[7] The Constitution was ratified by the requisite number of states (nine out of the 13) in 1788, but its implementation was set for March 4, 1789. The House began work on April 1, 1789, when it achieved a quorum for the first time.

During the first half of the 19th century, the House was frequently in conflict with the Senate over regionally divisive issues, including slavery. The North was much more populous than the South, and therefore dominated the House of Representatives. However, the North held no such advantage in the Senate, where the equal representation of states prevailed.

Regional conflict was most pronounced over the issue of slavery. One example of a provision repeatedly supported by the House but blocked by the Senate was the Wilmot Proviso, which sought to ban slavery in the land gained during the Mexican–American War. Conflict over slavery and other issues persisted until the Civil War (1861–1865), which began soon after several southern states attempted to secede from the Union. The war culminated in the South’s defeat and in the abolition of slavery. All southern senators except Andrew Johnson resigned their seats at the beginning of the war, and therefore the Senate did not hold the balance of power between North and South during the war.

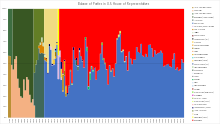

The years of Reconstruction that followed witnessed large majorities for the Republican Party, which many Americans associated with the Union’s victory in the Civil War and the ending of slavery. The Reconstruction period ended in about 1877; the ensuing era, known as the Gilded Age, was marked by sharp political divisions in the electorate. The Democratic Party and Republican Party each held majorities in the House at various times.

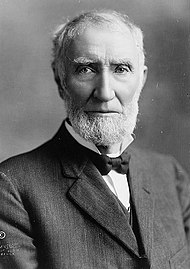

The late 19th and early 20th centuries also saw a dramatic increase in the power of the speaker of the House. The rise of the speaker’s influence began in the 1890s, during the tenure of Republican Thomas Brackett Reed. «Czar Reed», as he was nicknamed, attempted to put into effect his view that «The best system is to have one party govern and the other party watch.» The leadership structure of the House also developed during approximately the same period, with the positions of majority leader and minority leader being created in 1899. While the minority leader was the head of the minority party, the majority leader remained subordinate to the speaker. The speakership reached its zenith during the term of Republican Joseph Gurney Cannon, from 1903 to 1911. The speaker’s powers included chairmanship of the influential Rules Committee and the ability to appoint members of other House committees. However, these powers were curtailed in the «Revolution of 1910» because of the efforts of Democrats and dissatisfied Republicans who opposed Cannon’s heavy-handed tactics.

The Democratic Party dominated the House of Representatives during the administration of President Franklin D. Roosevelt (1933–1945), often winning over two-thirds of the seats. Both Democrats and Republicans were in power at various times during the next decade. The Democratic Party maintained control of the House from 1955 until 1995. In the mid-1970s, members passed major reforms that strengthened the power of sub-committees at the expense of committee chairs and allowed party leaders to nominate committee chairs. These actions were taken to undermine the seniority system, and to reduce the ability of a small number of senior members to obstruct legislation they did not favor. There was also a shift from the 1990s to greater control of the legislative program by the majority party; the power of party leaders (especially the speaker) grew considerably. According to historian Julian E. Zelizer, the majority Democrats minimized the number of staff positions available to the minority Republicans, kept them out of decision-making, and gerrymandered their home districts. Republican Newt Gingrich argued American democracy was being ruined by the Democrats’ tactics and that the GOP had to destroy the system before it could be saved. Cooperation in governance, says Zelizer, would have to be put aside until they deposed Speaker Wright and regained power. Gingrich brought an ethics complaint which led to Wright’s resignation in 1989. Gingrich gained support from the media and good government forces in his crusade to persuade Americans that the system was, in Gingrich’s words, «morally, intellectually and spiritually corrupt». Gingrich followed Wright’s successor, Democrat Tom Foley, as speaker after the Republican Revolution of 1994 gave his party control of the House.[8]

Gingrich attempted to pass a major legislative program, the Contract with America and made major reforms of the House, notably reducing the tenure of committee chairs to three two-year terms. Many elements of the Contract did not pass Congress, were vetoed by President Bill Clinton, or were substantially altered in negotiations with Clinton. However, after Republicans held control in the 1996 election, Clinton and the Gingrich-led House agreed on the first balanced federal budget in decades, along with a substantial tax cut.[9] The Republicans held on to the House until 2006, when the Democrats won control and Nancy Pelosi was subsequently elected by the House as the first female speaker. The Republicans retook the House in 2011, with the largest shift of power since the 1930s.[10] However, the Democrats retook the house in 2019, which became the largest shift of power to the Democrats since the 1970s. In the 2022 elections, Republicans took back control of the House, winning a slim majority.

Membership, qualifications, and apportionment

Apportionments

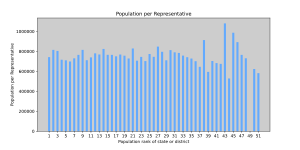

Under Article I, Section 2 of the Constitution, seats in the House of Representatives are apportioned among the states by population, as determined by the census conducted every ten years. Each state is entitled to at least one representative, however small its population.

The only constitutional rule relating to the size of the House states: «The Number of Representatives shall not exceed one for every thirty Thousand, but each State shall have at Least one Representative.»[11] Congress regularly increased the size of the House to account for population growth until it fixed the number of voting House members at 435 in 1911.[1] In 1959, upon the admission of Alaska and Hawaii, the number was temporarily increased to 437 (seating one representative from each of those states without changing existing apportionment), and returned to 435 four years later, after the reapportionment consequent to the 1960 census.

The Constitution does not provide for the representation of the District of Columbia or of territories. The District of Columbia and the territories of Puerto Rico, American Samoa, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, and the U.S. Virgin Islands are each represented by one non-voting delegate. Puerto Rico elects a resident commissioner, but other than having a four-year term, the resident commissioner’s role is identical to the delegates from the other territories. The five delegates and resident commissioner may participate in debates; before 2011,[12] they were also allowed to vote in committees and the Committee of the Whole when their votes would not be decisive.[13]

Redistricting

States entitled to more than one representative are divided into single-member districts. This has been a federal statutory requirement since 1967 pursuant to the act titled An Act For the relief of Doctor Ricardo Vallejo Samala and to provide for congressional redistricting.[14] Before that law, general ticket representation was used by some states.

States typically redraw district boundaries after each census, though they may do so at other times, such as the 2003 Texas redistricting. Each state determines its own district boundaries, either through legislation or through non-partisan panels. «Malapportionment» is unconstitutional and districts must be approximately equal in population (see Wesberry v. Sanders). Additionally, Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 prohibits redistricting plans that are intended to, or have the effect of, discriminating against racial or language minority voters.[15] Aside from malapportionment and discrimination against racial or language minorities, federal courts have allowed state legislatures to engage in gerrymandering to benefit political parties or incumbents.[16][17] In a 1984 case, Davis v. Bandemer, the Supreme Court held that gerrymandered districts could be struck down based on the Equal Protection Clause, but the Court did not articulate a standard for when districts are impermissibly gerrymandered. However, the Court overruled Davis in 2004 in Vieth v. Jubelirer, and Court precedent holds gerrymandering to be a political question. According to calculations made by Burt Neuborne using criteria set forth by the American Political Science Association, about 40 seats, less than 10% of the House membership, are chosen through a genuinely contested electoral process, given partisan gerrymandering.[18][19]

Qualifications

Article I, Section 2 of the Constitution sets three qualifications for representatives. Each representative must: (1) be at least twenty-five (25) years old; (2) have been a citizen of the United States for the past seven years; and (3) be (at the time of the election) an inhabitant of the state they represent. Members are not required to live in the districts they represent, but they traditionally do.[20] The age and citizenship qualifications for representatives are less than those for senators. The constitutional requirements of Article I, Section 2 for election to Congress are the maximum requirements that can be imposed on a candidate.[21] Therefore, Article I, Section 5, which permits each House to be the judge of the qualifications of its own members does not permit either House to establish additional qualifications. Likewise a State could not establish additional qualifications. William C. C. Claiborne served in the House below the minimum age of 25.[22]

Disqualification: under the Fourteenth Amendment, a federal or state officer who takes the requisite oath to support the Constitution, but later engages in rebellion or aids the enemies of the United States, is disqualified from becoming a representative. This post–Civil War provision was intended to prevent those who sided with the Confederacy from serving. However, disqualified individuals may serve if they gain the consent of two-thirds of both houses of Congress.

Elections

Elections for representatives are held in every even-numbered year, on Election Day the first Tuesday after the first Monday in November. Pursuant to the Uniform Congressional District Act, representatives must be elected from single-member districts. After a census is taken (in a year ending in 0), the year ending in 2 is the first year in which elections for U.S. House districts are based on that census (with the Congress based on those districts starting its term on the following January 3). As there is no legislation at the federal level mandating one particular system for elections to the House, systems are set at the state level. As of 2022, first-past-the-post or plurality voting is adopted in 46 states, ranked-choice or instant-runoff voting in two states (Alaska and Maine), and two-round system in two states (Georgia and Mississippi). Elected representatives serve a two-year term, with no term limit.

In most states, major party candidates for each district are nominated in partisan primary elections, typically held in spring to late summer. In some states, the Republican and Democratic parties choose their candidates for each district in their political conventions in spring or early summer, which often use unanimous voice votes to reflect either confidence in the incumbent or the result of bargaining in earlier private discussions. Exceptions can result in so-called floor fights—convention votes by delegates, with outcomes that can be hard to predict. Especially if a convention is closely divided, a losing candidate may contend further by meeting the conditions for a primary election. The courts generally do not consider ballot access rules for independent and third party candidates to be additional qualifications for holding office and no federal statutes regulate ballot access. As a result, the process to gain ballot access varies greatly from state to state, and in the case of a third party in the United States may be affected by results of previous years’ elections.

In 1967, Congress passed the Uniform Congressional District Act, which requires all representatives to be elected from single-member-districts.[23][24] Following the Wesberry v. Sanders decision, Congress was motivated by fears that courts would impose at-large plurality districts on states that did not redistrict to comply with the new mandates for districts roughly equal in population, and Congress also sought to prevent attempts by southern states to use such voting systems to dilute the vote of racial minorities.[25] Several states have used multi-member districts in the past, although only two states (Hawaii and New Mexico) used multi-member districts in 1967.[24] Louisiana is unique in that it holds an all-party primary election on the general Election Day with a subsequent runoff election between the top two finishers (regardless of party) if no candidate received a majority in the primary. The states of Washington and California use a similar (though not identical) system to that used by Louisiana.

Seats vacated during a term are filled through special elections, unless the vacancy occurs closer to the next general election date than a pre-established deadline. The term of a member chosen in a special election usually begins the next day, or as soon as the results are certified.

Non-voting delegates

Historically, many territories have sent non-voting delegates to the House. While their role has fluctuated over the years, today they have many of the same privileges as voting members, have a voice in committees, and can introduce bills on the floor, but cannot vote on the ultimate passage of bills. Presently, the District of Columbia and the five inhabited U.S. territories each elect a delegate. A seventh delegate, representing the Cherokee Nation, has been formally proposed but has not yet been seated.[26] An eighth delegate, representing the Choctaw Nation is guaranteed by treaty but has not yet been proposed. Additionally, some territories may choose to also elect shadow representatives, though these are not official members of the House and are separate individuals from their official delegates.

Terms

Representatives and delegates serve for two-year terms, while a resident commissioner (a kind of delegate) serves for four years. A term starts on January 3 following the election in November. The U.S. Constitution requires that vacancies in the House be filled with a special election. The term of the replacement member expires on the date that the original member’s would have expired.

The Constitution permits the House to expel a member with a two-thirds vote. In the history of the United States, only five members have been expelled from the House; in 1861, three were removed for supporting the Confederate states’ secession: Democrats John Bullock Clark of Missouri, John William Reid of Missouri, and Henry Cornelius Burnett of Kentucky. Democrat Michael Myers of Pennsylvania was expelled after his criminal conviction for accepting bribes in 1980, and Democrat James Traficant of Ohio was expelled in 2002 following his conviction for corruption.[27]

The House also has the power to formally censure or reprimand its members; censure or reprimand of a member requires only a simple majority, and does not remove that member from office.

Comparison to the Senate

As a check on the regional, popular, and rapidly changing politics of the House, the Senate has several distinct powers. For example, the «advice and consent» powers (such as the power to approve treaties and confirm members of the Cabinet) are a sole Senate privilege.[28] The House, however, has the exclusive power to initiate bills for raising revenue, to impeach officials, and to choose the president if a presidential candidate fails to get a majority of the Electoral College votes.[29] Both House and Senate confirmation is now required to fill a vacancy if the vice presidency is vacant, according to the provisions of the Twenty-fifth Amendment.[30][31] The Senate and House are further differentiated by term lengths and the number of districts represented: the Senate has longer terms of six years, fewer members (currently one hundred, two for each state), and (in all but seven delegations) larger constituencies per member. The Senate is referred to as the «upper» house, and the House of Representatives as the «lower» house.

Salary and benefits

Salaries

As of December 2014, the annual salary of each representative is $174,000,[32][33] the same as it is for each member of the Senate.[34] The speaker of the House and the majority and minority leaders earn more: $223,500 for the speaker and $193,400 for their party leaders (the same as Senate leaders).[33] A cost-of-living-adjustment (COLA) increase takes effect annually unless Congress votes not to accept it. Congress sets members’ salaries; however, the Twenty-seventh Amendment to the United States Constitution prohibits a change in salary (but not COLA[35]) from taking effect until after the next election of the whole House. Representatives are eligible for retirement benefits after serving for five years.[36] Outside pay is limited to 15% of congressional pay, and certain types of income involving a fiduciary responsibility or personal endorsement are prohibited. Salaries are not for life, only during active term.[33]

Titles

Representatives use the prefix «The Honorable» before their names. A member of the House is referred to as a representative, congressman, or congresswoman.

Representatives are usually identified in the media and other sources by party and state, and sometimes by congressional district, or a major city or community within their district. For example, Democratic House speaker Nancy Pelosi, who represents California’s 12th congressional district within San Francisco, may be identified as «D–California», «D–California–12» or «D–San Francisco».

A small number of representatives have elected to use the post nominal «MC» (for «member of Congress») after their names, a reflection of the Westminster system’s usage of «MP».[citation needed]

Pension

All members of Congress are automatically enrolled in the Federal Employees Retirement System, a pension system also used for federal civil servants, except the formula for calculating Congress members’ pension results in a 70% higher pension than other federal employees based on the first 20 years of service.[37] They become eligible to receive benefits after five years of service (two and one-half terms in the House). The FERS is composed of three elements:

- Social Security

- The FERS basic annuity, a monthly pension plan based on the number of years of service and the average of the three highest years of basic pay (70% higher pension than other federal employees based on the first 20 years of service)

- The Thrift Savings Plan, a 401(k)-like defined contribution plan for retirement account into which participants can deposit up to a maximum of $19,000 in 2019. Their employing agency matches employee contributions up to 5% of pay.

Members of Congress may retire with full benefits at age 62 after five years of service, at age 50 after twenty years of service, and at any age after twenty-five years of service.[37]

Tax deductions

Members of Congress are permitted to deduct up to $3,000 of living expenses per year incurred while living away from their district or home state.[38]

Health benefits

Before 2014, members of Congress and their staff had access to essentially the same health benefits as federal civil servants; they could voluntarily enroll in the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program (FEHBP), an employer-sponsored health insurance program, and were eligible to participate in other programs, such as the Federal Flexible Spending Account Program (FSAFEDS).[39]

However, Section 1312(d)(3)(D) of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) provided that the only health plans that the federal government can make available to members of Congress and certain congressional staff are those created under the ACA or offered through a health care exchange. The Office of Personnel Management promulgated a final rule to comply with Section 1312(d)(3)(D).[39] Under the rule, effective January 1, 2014, members and designated staff are no longer able to purchase FEHBP plans as active employees.[39] However, if members enroll in a health plan offered through a Small Business Health Options Program (SHOP) exchange, they remain eligible for an employer contribution toward coverage, and members and designated staff eligible for retirement may enroll in a FEHBP plan upon retirement.[39]

The ACA and the final rule do not affect members’ or staffers’ eligibility for Medicare benefits.[39] The ACA and the final rule also do not affect members’ and staffers’ eligibility for other health benefits related to federal employment, so members and staff are eligible to participate in FSAFEDS (which has three options within the program), the Federal Employees Dental and Vision Insurance Program, and the Federal Long Term Care Insurance Program.[39]

The Office of the Attending Physician at the U.S. Capitol provides members with health care for an annual fee.[39] The attending physician provides routine exams, consultations, and certain diagnostics, and may write prescriptions (although the office does not dispense them).[39] The office does not provide vision or dental care.[39]

Members (but not their dependents, and not former members) may also receive medical and emergency dental care at military treatment facilities.[39] There is no charge for outpatient care if it is provided in the National Capital Region, but members are billed at full reimbursement rates (set by the Department of Defense) for inpatient care.[39] (Outside the National Capital Region, charges are at full reimbursement rates for both inpatient and outpatient care).[39]

Personnel, mail and office expenses

House members are eligible for a Member’s Representational Allowance (MRA) to support them in their official and representational duties to their district.[40] The MRA is calculated based on three components: one for personnel, one for official office expenses and one for official or franked mail. The personnel allowance is the same for all members; the office and mail allowances vary based on the members’ district’s distance from Washington, D.C., the cost of office space in the member’s district, and the number of non-business addresses in their district. These three components are used to calculate a single MRA that can fund any expense—even though each component is calculated individually, the franking allowance can be used to pay for personnel expenses if the member so chooses. In 2011 this allowance averaged $1.4 million per member, and ranged from $1.35 to $1.67 million.[41]

The Personnel allowance was $944,671 per member in 2010. Each member may employ no more than 18 permanent employees. Members’ employees’ salary is capped at $168,411 as of 2009.[41]

Travel allowance

Before being sworn into office each member-elect and one staffer can be paid for one round trip between their home in their congressional district and Washington, D.C. for organization caucuses.[41] Members are allowed «a sum for travel based on the following formula: 64 times the rate per mile … multiplied by the mileage between Washington, DC, and the furthest point in a Member’s district, plus 10%.»[41] As of January 2012 the rate ranges from $0.41 to $1.32 per mile ($0.25 to $0.82/km) based on distance ranges between D.C. and the member’s district.[41]

Officers

Member officials

The party with a majority of seats in the House is known as the majority party. The next-largest party is the minority party. The speaker, committee chairs, and some other officials are generally from the majority party; they have counterparts (for instance, the «ranking members» of committees) in the minority party.

The Constitution provides that the House may choose its own speaker.[42] Although not explicitly required by the Constitution, every speaker has been a member of the House. The Constitution does not specify the duties and powers of the speaker, which are instead regulated by the rules and customs of the House. Speakers have a role both as a leader of the House and the leader of their party (which need not be the majority party; theoretically, a member of the minority party could be elected as speaker with the support of a fraction of members of the majority party). Under the Presidential Succession Act (1947), the speaker is second in the line of presidential succession after the vice president.

The speaker is the presiding officer of the House but does not preside over every debate. Instead, they delegate the responsibility of presiding to other members in most cases. The presiding officer sits in a chair in the front of the House chamber. The powers of the presiding officer are extensive; one important power is that of controlling the order in which members of the House speak. No member may make a speech or a motion unless they have first been recognized by the presiding officer. Moreover, the presiding officer may rule on a «point of order» (a member’s objection that a rule has been breached); the decision is subject to appeal to the whole House.

Speakers serve as chairs of their party’s steering committee, which is responsible for assigning party members to other House committees. The speaker chooses the chairs of standing committees, appoints most of the members of the Rules Committee, appoints all members of conference committees, and determines which committees consider bills.

Each party elects a floor leader, who is known as the majority leader or minority leader. The minority leader heads their party in the House, and the majority leader is their party’s second-highest-ranking official, behind the speaker. Party leaders decide what legislation members of their party should either support or oppose.

Each party also elects a Whip, who works to ensure that the party’s members vote as the party leadership desires. The majority whip in the House of Representatives is Tom Emmer, who is a member of the Republican Party. The minority whip is Katherine Clark, who is a member of the Democratic Party. The whip is supported by chief deputy whips

After the whips, the next ranking official in the House party’s leadership is the party conference chair (styled as the Republican conference chair and Democratic caucus chair).

After the conference chair, there are differences between each party’s subsequent leadership ranks. After the Democratic caucus chair is the campaign committee chair (Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee), then the co-chairs of the Steering Committee. For the Republicans it is the chair of the House Republican Policy Committee, followed by the campaign committee chairman (styled as the National Republican Congressional Committee).

The chairs of House committees, particularly influential standing committees such as Appropriations, Ways and Means, and Rules, are powerful but not officially part of the House leadership hierarchy. Until the post of majority leader was created, the chair of Ways and Means was the de facto majority leader.

Leadership and partisanship

When the presidency and Senate are controlled by a different party from the one controlling the House, the speaker can become the de facto «leader of the opposition». Some notable examples include Tip O’Neill in the 1980s, Newt Gingrich in the 1990s, John Boehner in the early 2010s, and Nancy Pelosi in the late 2000s and again in the late 2010s and early 2020s. Since the speaker is a partisan officer with substantial power to control the business of the House, the position is often used for partisan advantage.

In the instance when the presidency and both Houses of Congress are controlled by one party, the speaker normally takes a low profile and defers to the president. For that situation the House minority leader can play the role of a de facto «leader of the opposition», often more so than the Senate minority leader, due to the more partisan nature of the House and the greater role of leadership.

Non-member officials

The House is also served by several officials who are not members. The House’s chief such officer is the clerk, who maintains public records, prepares documents, and oversees junior officials, including pages until the discontinuation of House pages in 2011. The clerk also presides over the House at the beginning of each new Congress pending the election of a speaker. Another officer is the chief administrative officer, responsible for the day-to-day administrative support to the House of Representatives. This includes everything from payroll to foodservice.

The position of chief administrative officer (CAO) was created by the 104th Congress following the 1994 mid-term elections, replacing the positions of doorkeeper and director of non-legislative and financial services (created by the previous congress to administer the non-partisan functions of the House). The CAO also assumed some of the responsibilities of the House Information Services, which previously had been controlled directly by the Committee on House Administration, then headed by Representative Charlie Rose of North Carolina, along with the House «Folding Room».

The chaplain leads the House in prayer at the opening of the day. The sergeant at arms is the House’s chief law enforcement officer and maintains order and security on House premises. Finally, routine police work is handled by the United States Capitol Police, which is supervised by the Capitol Police Board, a body to which the sergeant at arms belongs, and chairs in even-numbered years.

Procedure

Daily procedures

Like the Senate, the House of Representatives meets in the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C. At one end of the chamber of the House is a rostrum from which the speaker, Speaker pro tempore, or (when in the Committee of the Whole) the chair presides.[43] The lower tier of the rostrum is used by clerks and other officials. Members’ seats are arranged in the chamber in a semicircular pattern facing the rostrum and are divided by a wide central aisle.[44] By tradition, Democrats sit on the left of the center aisle, while Republicans sit on the right, facing the presiding officer’s chair.[45] Sittings are normally held on weekdays; meetings on Saturdays and Sundays are rare. Sittings of the House are generally open to the public; visitors must obtain a House Gallery pass from a congressional office.[46] Sittings are broadcast live on television and have been streamed live on C-SPAN since March 19, 1979,[47] and on HouseLive, the official streaming service operated by the Clerk, since the early 2010s.

The procedure of the House depends not only on the rules, but also on a variety of customs, precedents, and traditions. In many cases, the House waives some of its stricter rules (including time limits on debates) by unanimous consent.[48] A member may block a unanimous consent agreement, but objections are rare. The presiding officer, the speaker of the House enforces the rules of the House, and may warn members who deviate from them. The speaker uses a gavel to maintain order.[49] Legislation to be considered by the House is placed in a box called the hopper.[50]

In one of its first resolutions, the U.S. House of Representatives established the Office of the Sergeant at Arms. In an American tradition adopted from English custom in 1789 by the first speaker of the House, Frederick Muhlenberg of Pennsylvania, the Mace of the United States House of Representatives is used to open all sessions of the House. It is also used during the inaugural ceremonies for all presidents of the United States. For daily sessions of the House, the sergeant at arms carries the mace ahead of the speaker in procession to the rostrum. It is placed on a green marble pedestal to the speaker’s right. When the House is in committee, the mace is moved to a pedestal next to the desk of the Sergeant at Arms.[51]

The Constitution provides that a majority of the House constitutes a quorum to do business.[52] Under the rules and customs of the House, a quorum is always assumed present unless a quorum call explicitly demonstrates otherwise. House rules prevent a member from making a point of order that a quorum is not present unless a question is being voted on. The presiding officer does not accept a point of order of no quorum during general debate, or when a question is not before the House.[53]

During debates, a member may speak only if called upon by the presiding officer. The presiding officer decides which members to recognize, and can therefore control the course of debate.[54] All speeches must be addressed to the presiding officer, using the words «Mr. Speaker» or «Madam Speaker». Only the presiding officer may be directly addressed in speeches; other members must be referred to in the third person. In most cases, members do not refer to each other only by name, but also by state, using forms such as «the gentleman from Virginia», «the distinguished gentlewoman from California», or «my distinguished friend from Alabama».

There are 448 permanent seats on the House Floor and four tables, two on each side. These tables are occupied by members of the committee that have brought a bill to the floor for consideration and by the party leadership. Members address the House from microphones at any table or «the well», the area immediately in front of the rostrum.[55]

Passage of legislation

Per the Constitution, the House of Representatives determines the rules according to which it passes legislation. Any of the rules can be changed with each new Congress, but in practice each new session amends a standing set of rules built up over the history of the body in an early resolution published for public inspection.[56] Before legislation reaches the floor of the House, the Rules Committee normally passes a rule to govern debate on that measure (which then must be passed by the full House before it becomes effective). For instance, the committee determines if amendments to the bill are permitted. An «open rule» permits all germane amendments, but a «closed rule» restricts or even prohibits amendment. Debate on a bill is generally restricted to one hour, equally divided between the majority and minority parties. Each side is led during the debate by a «floor manager», who allocates debate time to members who wish to speak. On contentious matters, many members may wish to speak; thus, a member may receive as little as one minute, or even thirty seconds, to make their point.[57]

When debate concludes, the motion is put to a vote.[58] In many cases, the House votes by voice vote; the presiding officer puts the question, and members respond either «yea!» or «aye!» (in favor of the motion) or «nay!» or «no!» (against the motion). The presiding officer then announces the result of the voice vote. A member may, however, challenge the presiding officer’s assessment and «request the yeas and nays» or «request a recorded vote». The request may be granted only if it is seconded by one-fifth of the members present. Traditionally, however, members of Congress second requests for recorded votes as a matter of courtesy. Some votes are always recorded, such as those on the annual budget.[59]

A recorded vote may be taken in one of three different ways. One is electronically. Members use a personal identification card to record their votes at 46 voting stations in the chamber. Votes are usually held in this way. A second mode of recorded vote is by teller. Members hand in colored cards to indicate their votes: green for «yea», red for «nay», and orange for «present» (i.e., to abstain). Teller votes are normally held only when electronic voting breaks down. Finally, the House may conduct a roll call vote. The Clerk reads the list of members of the House, each of whom announces their vote when their name is called. This procedure is only used rarely (and usually for ceremonial occasions, such as for the election of a speaker) because of the time consumed by calling over four hundred names.[59]

Voting traditionally lasts for, at most, fifteen minutes, but it may be extended if the leadership needs to «whip» more members into alignment.[59] The 2003 vote on the prescription drug benefit was open for three hours, from 3:00 to 6:00 a.m., to receive four additional votes, three of which were necessary to pass the legislation.[60] The 2005 vote on the Central American Free Trade Agreement was open for one hour, from 11:00 p.m. to midnight.[61] An October 2005 vote on facilitating refinery construction was kept open for forty minutes.[62]

Presiding officers may vote like other members. They may not, however, vote twice in the event of a tie; rather, a tie vote defeats the motion.[63]

Committees

The House uses committees and their subcommittees for a variety of purposes, including the review of bills and the oversight of the executive branch. The appointment of committee members is formally made by the whole House, but the choice of members is actually made by the political parties. Generally, each party honors the preferences of individual members, giving priority on the basis of seniority. Historically, membership on committees has been in rough proportion to the party’s strength in the House, with two exceptions: on the Rules Committee, the majority party fills nine of the thirteen seats;[64] and on the Ethics Committee, each party has an equal number of seats.[65] However, when party control in the House is closely divided, extra seats on committees are sometimes allocated to the majority party. In the 109th Congress, for example, the Republicans controlled about 53% of the House, but had 54% of the Appropriations Committee members, 55% of the members on the Energy and Commerce Committee, 58% of the members on the Judiciary Committee, and 69% of the members on the Rules Committee.

The largest committee of the House is the Committee of the Whole, which, as its name suggests, consists of all members of the House. The Committee meets in the House chamber; it may consider and amend bills, but may not grant them final passage. Generally, the debate procedures of the Committee of the Whole are more flexible than those of the House itself. One advantage of the Committee of the Whole is its ability to include otherwise non-voting members of Congress.

Most committee work is performed by twenty standing committees, each of which has jurisdiction over a specific set of issues, such as Agriculture or Foreign Affairs. Each standing committee considers, amends, and reports bills that fall under its jurisdiction. Committees have extensive powers with regard to bills; they may block legislation from reaching the floor of the House. Standing committees also oversee the departments and agencies of the executive branch. In discharging their duties, standing committees have the power to hold hearings and to subpoena witnesses and evidence.

The House also has one permanent committee that is not a standing committee, the Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence, and occasionally may establish temporary or advisory committees, such as the Select Committee on Energy Independence and Global Warming. This latter committee, created in the 110th Congress and reauthorized for the 111th, has no jurisdiction over legislation and must be chartered anew at the start of every Congress. The House also appoints members to serve on joint committees, which include members of the Senate and House. Some joint committees oversee independent government bodies; for instance, the Joint Committee on the Library oversees the Library of Congress. Other joint committees serve to make advisory reports; for example, there exists a Joint Committee on Taxation. Bills and nominees are not referred to joint committees. Hence, the power of joint committees is considerably lower than those of standing committees.

Each House committee and subcommittee is led by a chairman (always a member of the majority party). From 1910 to the 1970s, committee chairs were powerful. Woodrow Wilson in his classic study,[66] suggested:

Power is nowhere concentrated; it is rather deliberately and of set policy scattered amongst many small chiefs. It is divided up, as it were, into forty-seven seigniories, in each of which a Standing Committee is the court-baron and its chairman lord-proprietor. These petty barons, some of them not a little powerful, but none of them within the reach of the full powers of rule, may at will exercise almost despotic sway within their own shires, and may sometimes threaten to convulse even the realm itself.

From 1910 to 1975 committee and subcommittee chairmanship was determined purely by seniority; members of Congress sometimes had to wait 30 years to get one, but their chairship was independent of party leadership. The rules were changed in 1975 to permit party caucuses to elect chairs, shifting power upward to the party leaders. In 1995, Republicans under Newt Gingrich set a limit of three two-year terms for committee chairs. The chairman’s powers are extensive; he controls the committee/subcommittee agenda, and may prevent the committee from dealing with a bill. The senior member of the minority party is known as the Ranking Member. In some committees like Appropriations, partisan disputes are few.

Legislative functions

Most bills may be introduced in either House of Congress. However, the Constitution states, «All Bills for raising Revenue shall originate in the House of Representatives.» Because of the Origination Clause, the Senate cannot initiate bills imposing taxes. This provision barring the Senate from introducing revenue bills is based on the practice of the British Parliament, in which only the House of Commons may originate such measures. Furthermore, congressional tradition holds that the House of Representatives originates appropriation bills.

Although it cannot originate revenue bills, the Senate retains the power to amend or reject them. Woodrow Wilson wrote the following about appropriations bills:[67]

[T]he constitutional prerogative of the House has been held to apply to all the general appropriations bills, and the Senate’s right to amend these has been allowed the widest possible scope. The upper house may add to them what it pleases; may go altogether outside of their original provisions and tack to them entirely new features of legislation, altering not only the amounts but even the objects of expenditure, and making out of the materials sent them by the popular chamber measures of an almost totally new character.

The approval of the Senate and the House of Representatives is required for a bill to become law. Both Houses must pass the same version of the bill; if there are differences, they may be resolved by a conference committee, which includes members of both bodies. For the stages through which bills pass in the Senate, see Act of Congress.

The president may veto a bill passed by the House and Senate. If they do, the bill does not become law unless each House, by a two-thirds vote, votes to override the veto.

Checks and balances

The Constitution provides that the Senate’s «advice and consent» is necessary for the president to make appointments and to ratify treaties. Thus, with its potential to frustrate presidential appointments, the Senate is more powerful than the House.

The Constitution empowers the House of Representatives to impeach federal officials for «Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors» and empowers the Senate to try such impeachments. The House may approve «articles of impeachment» by a simple majority vote; however, a two-thirds vote is required for conviction in the Senate. A convicted official is automatically removed from office and may be disqualified from holding future office under the United States. No further punishment is permitted during the impeachment proceedings; however, the party may face criminal penalties in a normal court of law.

In the history of the United States, the House of Representatives has impeached seventeen officials, of whom seven were convicted. (Another, Richard Nixon, resigned after the House Judiciary Committee passed articles of impeachment but before a formal impeachment vote by the full House.) Only three presidents of the United States have ever been impeached: Andrew Johnson in 1868, Bill Clinton in 1998, and Donald Trump in 2019 and in 2021. The trials of Johnson, Clinton and Trump all ended in acquittal; in Johnson’s case, the Senate fell one vote short of the two-thirds majority required for conviction.

Under the Twelfth Amendment, the House has the power to elect the president if no presidential candidate receives a majority of votes in the Electoral College. The Twelfth Amendment requires the House to choose from the three candidates with the highest numbers of electoral votes. The Constitution provides that «the votes shall be taken by states, the representation from each state having one vote». It is rare for no presidential candidate to receive a majority of electoral votes. In the history of the United States, the House has only had to choose a president twice. In 1800, which was before the adoption of the Twelfth Amendment, it elected Thomas Jefferson over Aaron Burr. In 1824, it elected John Quincy Adams over Andrew Jackson and William H. Crawford. (If no vice-presidential candidate receives a majority of the electoral votes, the Senate elects the vice president from the two candidates with the highest numbers of electoral votes.)

Latest election results and party standings

As of September 19, 2023[68]

| 221 | 212 |

| Republican | Democratic |

| Affiliation | Members | Delegates/resident commissioner (non-voting) |

State majorities |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | 221 | 3 | 29 | |

| Democratic | 212 | 3 | 25 | |

| Vacant | 2 | |||

| Total | 435 | 6 | 56 | |

| Majority[c] | 4 |

See also

- 2022 United States House of Representatives elections

- List of current members of the United States House of Representatives

- Third-party members of the United States House of Representatives

- U.S. representative bibliography (congressional memoirs)

- Women in the United States House of Representatives

References

Footnotes

- ^ Alaska (for its primary elections only), California, and Washington additionally utilize a nonpartisan blanket primary, and Mississippi uses the two-round system, for their respective primary elections.

- ^ Louisiana uses a Louisiana primary.

- ^ The number of the majority party’s voting representatives in the House in excess of the minimum number required to have an absolute majority of voting representatives.

Citations

- ^ a b See Public Law 62-5 of 1911, though Congress has the authority to change that number.

- ^ «Explainer: Why Does The U.S. House Have 435 Members?». NPR. April 20, 2021. Archived from the original on March 29, 2022. Retrieved April 1, 2022.

- ^ United States House of Representatives Archived June 24, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, Ballotpedia. Accessed November 23, 2016. «There are six states with only one representative: Alaska, Delaware, North Dakota, South Dakota, Vermont and Wyoming.»

- ^ Section 7 of Article 1 of the Constitution

- ^ Article 1, Section 2, and in the 12th Amendment

- ^ «Party In Power – Congress and Presidency – A Visual Guide To The Balance of Power In Congress, 1945–2008». Uspolitics.about.com. Archived from the original on November 1, 2012. Retrieved September 17, 2012.

- ^ a b c «Delegates of the Continental Congress Who Signed the United States Constitution» Archived January 14, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, United States House of Representatives. Accessed February 19, 2017. «While some believed the Articles should be ‘corrected and enlarged as to accomplish the objects proposed by their institution,’ the Virginia Plan called for completely replacing it with a strong central government based on popular consent and proportional representation…. The Virginia Plan received support from states with large populations such as Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, and South Carolina. A number of smaller states, however, proposed the ‘New Jersey Plan,’ drafted by William Paterson, which retained the essential features of the original Articles: a unicameral legislature where all states had equal representation, the appointment of a plural executive, and a supreme court of limited jurisdiction…. The committee’s report, dubbed the Great Compromise, ironed out many contentious points. It resolved the delegates’ sharpest disagreement by prescribing a bicameral legislature with proportional representation in the House and equal state representation in the Senate. After two more months of intense debates and revisions, the delegates produced the document we now know as the Constitution, which expanded the power of the central government while protecting the prerogatives of the states.»

- ^ Julian E. Zelizer, Burning Down the House: Newt Gingrich, the Fall of a Speaker, and the Rise of the New Republican Party (2020).

- ^ Balanced Budget: HR 2015, FY 1998 Budget Reconciliation / Spending; Tax Cut: HR 2014, FY 1998 Budget Reconciliation – Revenue

- ^ Neuman, Scott (November 3, 2010). «Obama, GOP Grapple With power shift». NPR. Archived from the original on June 10, 2020. Retrieved July 2, 2011.

- ^ Article I, Section 2.

- ^ «New House Majority Introduces Rules Changes». NPR. January 5, 2011. Archived from the original on February 6, 2011. Retrieved July 2, 2011.

- ^ See H.Res. 78, passed January 24, 2007. On April 19, 2007, the House of Representatives passed the DC House Voting Rights Act of 2007, a bill «to provide for the treatment of the District of Columbia as a Congressional district for purposes of representation in the House of Representatives, and for other purposes» by a vote of 241–177. That bill proposes to increase the House membership by two, making 437 members, by converting the District of Columbia delegate into a member, and (until the 2010 census) grant one membership to Utah, which is the state next in line to receive an additional district based on its population after the 2000 Census. The bill was under consideration in the U.S. Senate during the 2007 session.

- ^ 2 U.S.C. § 2c «no district to elect more than one Representative»

- ^ «Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act». Civil Rights Division Voting FAQ. US Dept. of Justice. Archived from the original on April 15, 2014. Retrieved April 27, 2014.

- ^ Bazelon, Emily (November 9, 2012). «The Supreme Court may gut the Voting Rights Act and make gerrymandering much worse». Slate. Archived from the original on September 26, 2013. Retrieved September 29, 2013.

- ^ Eaton, Whitney M. (May 2006). «Where Do We Draw the Line? Partisan Gerrymandering and the State of Texas». University of Richmond Law Review. Archived from the original on October 9, 2013.

- ^ Burt Neuborne Madison’s Music: On Reading the First Amendment, Archived December 14, 2019, at the Wayback Machine The New Press 2015

- ^ David Cole, ‘Free Speech, Big Money, Bad Elections,’ Archived March 14, 2016, at the Wayback Machine in New York Review of Books, November 5, 2015, pp.24–25 p.24.

- ^ «Qualifications of Members of Congress». Onecle Inc. Archived from the original on January 23, 2013. Retrieved January 26, 2013.

- ^ See Powell v. McCormack, a U.S. Supreme Court case from 1969

- ^ «The Youngest Representative in House History, William Charles Cole Claiborne | US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives». history.house.gov. Archived from the original on October 3, 2020. Retrieved October 6, 2020.

- ^ 2 U.S.C. § 2c

- ^ a b Schaller, Thomas (March 21, 2013). «Multi-Member Districts: Just a Thing of the Past?». University of Virginia Center for Politics. Archived from the original on October 8, 2015. Retrieved November 2, 2015.

- ^ «The 1967 Single-Member District Mandate». fairvote.org. Archived from the original on November 11, 2012. Retrieved September 1, 2012.

- ^ Krehbiel-Burton, Lenzy (August 23, 2019). «Citing treaties, Cherokees call on Congress to seat delegate from tribe». Tulsa World. Tulsa, Oklahoma. Archived from the original on January 14, 2021. Retrieved August 24, 2019.

- ^ «Expulsion, Censure, Reprimand, and Fine: Legislative Discipline in the House of Representatives» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 7, 2010. Retrieved August 23, 2010.

- ^ Senate Legislative Process Archived April 4, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, U.S. Senate . Retrieved February 3, 2010.

- ^ The Legislative Branch Archived January 20, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, The White House. Retrieved February 3, 2010.

- ^ Section 2 reads: «Whenever there is a vacancy in the office of the Vice President, the President shall nominate a Vice President who shall take office upon confirmation by a majority vote of both Houses of Congress.»

- ^ Feerick, John. «Essays on Amendment XXV: Presidential Succession». The Heritage Guide to the Constitution. The Heritage Foundatio. Archived from the original on August 22, 2020.

- ^ «Salaries and Benefits of U.S. Congress Members». Archived from the original on January 14, 2021. Retrieved December 24, 2014.

- ^ a b c Brudnick, Ida A. (January 4, 2012). «Congressional Salaries and Allowances» (PDF). CRS Report for Congress. United States House of Representatives. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 12, 2019. Retrieved December 2, 2012.

- ^ «Senate Salaries since 1789». United States Senate. Archived from the original on January 14, 2021. Retrieved December 14, 2020.

- ^ Schaffer v. Clinton

- ^ Brudnick, Ida A. (June 28, 2011). «Congressional Salaries and Allowances». Archived from the original on August 1, 2016. Retrieved November 22, 2011.

- ^ a b Congressional Research Service (August 8, 2019). «Retirement Benefits for Members of Congress». CRS Report for Congress. United States Senate.

- ^ Congressional Research Service. «Congressional Salaries and Allowances» (PDF). CRS Report for Congress. United States House of Representatives. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 12, 2019. Retrieved September 21, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Annie L. Mach & Ada S. Cornell, Health Benefits for Members of Congress and Certain Congressional Staff Archived January 14, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, Congressional Research Service, February 18, 2014.

- ^ Brudnick, Ida A. (September 27, 2017). Members’ Representational Allowance: History and Usage (PDF). Washington D.C.: Congressional Research Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 14, 2021. Retrieved October 24, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Brudnick, Ida. «Congressional Salaries and Allowances» (PDF). Congressional Research Service Report for Congress. United States House of Representatives. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 10, 2020. Retrieved September 21, 2012.

- ^ Article I Archived January 28, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, Legal Information Institute, Cornell University Law School . Retrieved February 3, 2010.

- ^ «The Rostrum». U.S. House of Representatives. Office of the Historian. Archived from the original on January 13, 2015. Retrieved January 12, 2015.

- ^ «Explore Capitol Hill: House Chamber». Architect of the Capitol. Archived from the original on January 14, 2015. Retrieved January 12, 2015.

- ^ Ritchie, Donald A. (2006). The Congress of the United States: A Student Companion (3 ed.). New York, New York: Oxford University Press. p. 195. ISBN 978-0-19-530924-9. Archived from the original on January 14, 2021. Retrieved January 10, 2015.

Lowenthal, Alan. «Congress U». U.S. House of Representatives. Archived from the original on January 13, 2015. Retrieved January 12, 2015.

«What’s in the House Chamber». Archived from the original on October 30, 2013. Retrieved November 21, 2013. - ^ «Access to Congress». Digital Media Law Project. Berkman Center for Internet and Society. Archived from the original on January 13, 2015. Retrieved January 12, 2015.

«U.S. House of Representatives». The District. Archived from the original on January 13, 2015. Retrieved January 12, 2015. - ^ Davis, Susan (March 19, 2014). «Not everyone is a fan of C-SPAN cameras in Congress». USA Today. Archived from the original on January 14, 2021. Retrieved January 12, 2015.