ГЕНЕРАЛЫ МОРСКОЙ ПЕХОТЫ И БЕРЕГОВЫХ ВОЙСК ВМФ РОССИИ

Ива́н Си́дорович Скура́тов — российский и советский военный деятель, генерал-полковник, доктор военных наук, академик Академии военных наук.

Родился 2 июня 1940 году в Липецкой области в семье колхозников.

В 1964 году окончил Черноморское высшее военно-морское училище им. П. С. Нахимова.

После окончания училища до 1971 года служил на Тихоокеанском флоте, где прошёл путь от должности начальника отделения до командира ракетной береговой части.

C 1972 года по 1974 год — был слушателем Военно-морской академии им. Адмирала Н. Г. Кузнецова.

С 1977 года — командир берегового ракетного полка;

С 1979 года по 1985 год — начальник береговых ракетно-артиллерийских войск и морской пехоты БФ;

В 1987 году — окончил Военную академию Генерального штаба ВС СССР;

C 1987 года — главный специалист береговых ракетно-артиллерийских войск ВМФ;

C 1989 года — начальник береговых войск и морской пехоты ВМФ ВС СССР;

C 1993 года — командующий береговыми войсками ВМФ;

В 1993 году — защитил докторскую диссертацию;

В 1994 году — присвоено воинское звание генерал-полковник;

С 1995 года — в запасе.

С 2 июня 2005 года — в отставке.

Председатель Попечительского совета Фонда поддержки Героев Советского Союза и Героев Российской Федерации имени генерала Е. Н. Кочешкова.

Член Центрального Совета Всероссийской общественной организации морских пехотинцев «Тайфун»

Генерал-полковник Яковлев Валентин Алексеевич

Родился 7 мая 1942 г.в селе Торьял, Новоторьялского района Марийской АССР.

1961-1965 г.г. Ленинградское Высшее Общевойсковое командное училище имени С.М. Кирова.

В 1965 году был направлен для прохождения службы на Дважды Краснознамённый Балтийский флот, командиром взвода морской пехоты в 336 отдельный гвардейский орденов Суворова и Александра Невского полк морской пехоты.

В 1966 году в составе первого батальона морской пехоты убыл для прохождения службы на Краснознамённый Черноморский флот.

В 1966 году лейтенант В.А. Яковлев в составе роты морской пехоты КЧФ принимал участие в первой в истории боевой службе морской пехоты СССР на крейсере «Слава» в Средиземное море.

1966-1969 г.г.- 810 отдельный полк Краснознаменного Черноморского Флота (командир взвода, роты морской пехоты).

1969-1972 г.г.- Военная Академия им. М.В. Фрунзе(слушатель).

1972-1978 г.г.- 810 отдельный полк морской пехоты КЧФ (начальник штаба, командир).

1978-1980 г.г.- 126 мотострелковая дивизия Одесского военного округа (начальник штаба, командир).

1980-1982 г.г.- 55 дивизии морской пехоты Краснознаменного Тихоокеанского Флота (Командир)

1982-1984 г.г.- Военная Академия Генерального Штаба им. К.Е. Ворошилова (слушатель).

1984-1987 г.г.- командир армейского корпуса Одесского военного округа.

1987-1988 г.г.- военный советник Вьетнамская народная республика.

1988-1991 г.г.- начальник управления ГУК МО СССР

1991-1996 г.г.- Первый заместитель начальника Главного управления кадров МО РФ.

1996-1998 г.г.- администрация Президента Российской Федерации.

За безупречную службу в Вооруженных силах удостоен:

Ордена « За службу Родине в Вооруженных силах СССР» III и II степени, а также 24 медали.

В.А. Яковлев неоднократно выполнял задачи по несению боевой службы в Средиземном море и выполнял Интернациональный долг «в горячих точках» мира: Афганистан, Вьетнам, Египет .

ОБЩЕСТВЕННАЯ РАБОТА.

В 1997 году генерал — полковник В.А. Яковлев избран Президентом Московской общественной организации морских пехотинцев «Сатурн».

В 2001 году избран Президентом Межрегиональной общественной организации морских пехотинцев «Тайфун».

В 2006 году избран Президентом Всероссийской общественной организации морских пехотинцев «Тайфун».

В 2010 избран Председателем Всероссийской общественной организации морских пехотинцев «Тайфун».

Романенко Владимир Иванович, генерал-майор

Начальник Береговых войск и морской пехоты ВМФ России (1995-1996г.г.), Начальник Береговых войск и морской пехоты Черноморского флота России (1986 – 1995г.), Первый заместитель Командующего Береговыми войсками и морской пехотой Тихоокеанского флота (1985-1986г.).

Родился 3 февраля 1945 года в городе Новороссийске

В 1963 году Владимир Иванович после окончания средней школы № 41 города Севастополя поступил в Черноморское высшее военно-морское училище им. П. С. Нахимова. Окончил: училище в 1968 году по специальности «ракетно-артиллерийское вооружение», Военно-морскую Академию по специальности «командная» в 1984 году, в Дипломатической Академии МИД России защитил диссертацию и стал кандидатом политических наук.

Награды: Ордена – «Красной звезды», «За службу Родине III степени» и 17 медалей.

Военная служба: Службу начал лейтенантом на артиллерийской батарее Тихоокеанского флота на острове Сахалин. В 1970 году командир вновь сформированной артиллерийской батареи, С 1972 по 1974 годы — военный советник военно-морского флота Сомали в порту Бербера, в Аденском заливе. С 1974 по 1982 годы последовательно командовал ракетным дивизионом, был начальником штаба полка, командиром полка, заместителем Начальника береговых ракетно-артиллерийских войск ТОФ. С 1985 по 1986 годы — первый заместитель Командующего Береговыми войсками ТОФ. После назначения Начальником береговых войск и морской пехоты Черноморского флота в 1986 году В период раздела Черноморского флота 1991 – 1995 годов, морская пехота под его командованием явилась надежным инструментом Командующих Черноморским флотом адмирала И. В. Касатонова и адмирала Э. Д. Балтина по сохранению флота в составе Вооруженных Сил России. В 1993 — 1995 годах успешно руководил боевыми операциями морской пехоты флота в Абхазии и Грузии, за что неоднократно был поощрен командованием. В 1995 – 1996 гг. командуя Береговыми войсками и морской пехотой ВМФ России успешно завершил вывод частей морской пехоты ВМФ из первой Чеченской компании.

После завершения военной службы, с февраля 1997 года по апрель 2008 года, работал в Институте стран СНГ первым заместителем Директора Института. За этот период была проделана большая работа по поддержке соотечественников за рубежом, созданию и обновлению законодательной базы РФ, решению практических вопросов отстаивания интересов России в странах СНГ.

В октябре 2013 утверждён в должности заместитель председателя «Российского Союза ветеранов» — начальник управления.

Генерал-лейтенант Шилов Павел Сергеевич

Родился 22 сентября 1948 года

1966-1970 г.г.- Бакинское Высшее Общевойсковое Командное Училище.

1970-1976 г.г.- 810 отдельный полк Краснознаменного Черноморского Флота (командир взвода, роты морской пехоты).

1976-1979 г.г.- Военная Академия им. М.В. Фрунзе(слушатель).

1979-1990 г.г.-55-я дивизия морской пехоты Краснознамённого Тихоокеанского флота (заместитель командира полка, начальник штаба, командир полка, начальник штаба дивизии) .

1990-1997 г.г.- Заместитель начальника штаба, начальник штаба Береговых войск ВМФ.

1997-2003 г.г.- Начальник Береговых войск Военно–Морского Флота.

П.С. Шилов неоднократно выполнял задачи по несению боевой службы в Средиземном море и выполнял Конституционный долг «в горячих точках» мира: Египет и в Северо — Кавказском регионе в 1995 г., 1999-2002 г.г .

За безупречную службу в Вооруженных силах удостоен:

Орденов «Мужества», «За военные заслуги», « За службу Родине в Вооруженных силах СССР» III степени и 15 медалей.

ОБЩЕСТВЕННАЯ РАБОТА.

В 1997 году генерал — лейтенант П.С. Шилов избран вице — президентом Московской общественной организации морских пехотинцев «Сатурн».

В 2001 году избран вице — президентом Межрегиональной общественной организации морских пехотинцев «Тайфун».

В 2006 году избран вице — президентом Всероссийской общественной организации морских пехотинцев «Тайфун», Председателем Центрального Совета Воо МП «Тайфун».

генерал-лейтенант Игорь Евгеньевич СТАРЧЕУС

Старчеус Игорь Евгеньевич родился 22 февраля 1955 года. Окончил Киевское суворовское училище, Омское ВОКУ, служил в разведподразделениях в Группе советских войск в Германии, командовал разведбатом в Туркестанском военном округе. После окончания Бронетанковой академии в 1988 г. был начальником штаба полка морской пехоты ТОФ, командиром полка, начальником штаба дивизии морской пехоты, заместителем начальника береговых войск ТОФ, затем — начальником штаба береговых войск. С должности заместителя командующего группировкой сил и войск Северо-Востока по береговым войскам в августе 2002 года назначен начальником сухопутных и береговых войск Тихоокеанского флота. В начале 2005 года возглавил морскую пехоту всего ВМФ.

Награжден орденом «За военные заслуги» и многими медалями.

Начальник береговых войск ВМФ России генерал-лейтенант Колпаченко Александр Николаевич, первый заместитель председателя ВОО МП «ТАЙФУН»

Родился 12 января 1959 года в городе Александрии Кировоградской области (ныне Украина).

В 1980 году окончил Рязанское высшее воздушно-десантное командное училище

Службу проходил в должностях:

командира взвода разведывательной роты 104 пдп 76 гв. Черниговской вдд (г.Псков).

С 1984 по 1986 годы служил в в Афганистане, где командовал разведывательной ротой 317 пдп.

С 1986 года служил в 104-м пдп, где последовательно прошел должности от командира разведывательной роты до командира парашютно-десантного батальона.

В 1992 году — слушатель Военной академии им. М.В.Фрунзе.

По окончании академии в 1995 году был назначен заместителем командира полка в 242 учебный центр ВДВ (г.Омск).

В 1997 году назначен командиром полка.

С 2000 по 2003 годы службу проходил в должности начальника штаба 7 гв. вдд (г.Новороссийск).

В июле 2003 года вернулся в Омск, возглавив 242 учебный центр ВДВ.

В июне 2005 года назначен командиром 76 гв. Черниговской вдд (г.Псков).

С 2009 года — начальник Береговых войск ВМФ РФ.

В декабре 2014 года присвоено воинское звание генерал-лейтенант.

Женат, двое детей. Старший сын закончил Краснодарское военное училище. Младший сын закончил Балтийский морской институт им. Ф.Ф.Ушакова (филиал Военного учебно-научного центра ВМФ «Военно-морская академия имени Адмирала Флота Советского Союза Н. Г. Кузнецова» в Калининграде), сейчас служит на Балтийском флоте, офицер корвета «Сообразительный». Есть внучка.

Государственные награды: два ордена Красной Звезды, ордена «За службу Родине в Вооруженных Силах СССР» III степени, «За военные заслуги». Награждён юбилейными и памятными медалями СССР и России.

ПЕРВЫЙ ЗАМЕСТИТЕЛЬ ПРЕДСЕДАТЕЛЯ ВСЕРОССИЙСКОЙ ОБЩЕСТВЕННОЙ ОРГАНИЗАЦИИ МОРСКИХ ПЕХОТИНЦЕВ «ТАЙФУН», ЧЛЕН ЦЕНТРАЛЬНОГО СОВЕТА

Начальник штаба береговых войск ВМФ России генерал-майор Александр Заставский. (2004 — 2009 годы)

Генерал-майор Заставский Александр Николаевич, родился 23 января 1954 года в Запорожской области. После окончания средней школы в 1971 году поступил в Черноморское ВВМУ им.П.С.Нахимова на береговой факультет. В 1976 году окончил училище по специальности «береговые ракетные комплексы».

С 1976 г. по 1988 г. проходил службу в 501 отдельном береговом ракетном полку Северного флота (дислокация на полуострове Рыбачий) в должностях начальник отделения автопилотов, заместитель командира батареи, командир батареи, заместитель командира дивизиона, командир дивизиона.

С 1988г. по 1991 г. слушатель командного факультета Военно-Морской академии.

С 1991г. по 1993г. проходил службу в Управлении Береговых войск СФ в должности заместителя начальника отдела БРАВ.

С 1993 г. по 1996 г. – командир 522 отдельной береговой ракетно-артиллерийской бригады СФ. В период командования бригадой обеспечивал силами личного состава выполнение ракетных стрельб береговыми ракетчиками БФ и ЧФ. В 1995 г. дивизионы бригады выполнили ракетные стрельбы с позиционных районов на п-ове Рыбачий в составе береговой ударной группы (БУГ) совместно с ракетными кораблями СФ. В 1994г. бригада передислоцирована в п. Оленья губа.

С 1996 г. по 1997 г. – командир 1-го Центрального флотского экипажа в г. Москве.

С 1997г. по 2001 г. – заместитель начальника штаба БВ ВМФ.

С 2001г. по 2009 г. – начальник штаба — первый заместитель начальника БВ ВМФ. В декабре 2002г. присвоено воинское звание генерал-майор.

С января 2004г. по февраль 2005 г. исполнял обязанности Начальника Береговых войск ВМФ.

В 1999 г. в составе оперативной группы ВМФ участвовал в контртеррористической операции на Северном Кавказе.

Награжден орденом «За военные заслуги», медалью ордена «За заслуги перед Отечеством» 2 степени, наградным огнестрельным оружием, другими медалями СССР и РФ.

Генерал-майор Заставский Александр Николаевич член Центрального Совета Всероссийской общественной организации морских пехотинцев «Тайфун»

генерал-майор Досугов Анатолий Сергеевич

Родился 12 сентября 1954 года в городе Апрелевка Наро-Фоминского района Московской области в семье военнослужащего, по национальности русский.

В 1972 году окончил 10 классов Московского суворовского училища и поступил в Московское высшее общевойсковое командное училище имени Верховного Совета РСФСР.

В июле 1976 года направлен в распоряжение командующего ЦГВ на должность командира мотострелкового взвода, а с октября 1979 года на должность командира мотострелковой роты войсковой части 265-го гв. мсп.

В январе 1980 года был направлен в Афганистан 122 мсп 201 мсд, где участвовал в боевых действиях по июнь 1981 года.

С июня 1981 года по июнь 1982 года на должности начальника штаба мотострелкового батальона в г. Калинин (ныне г. Тверь).

В июне 1982 года был направлен на Тихоокеанский флот, где проходил службу на должности начальника штаба батальона морской пехоты, а с марта 1983 года — на должности заместителя начальника штаба полка 390-го полка морской пехоты 55 дмп.

1984-1987 годы — слушатель Военной академии имени М.В. Фрунзе.

В августе 1987 года направлен на должность заместителя начальника оперативного отделения штаба 55 дмп, с августа 1989 года — командир 106 пмп, а с октября 1990 года — командир 390 пмп Тихоокеанского флота

С октября 1993 года проходил службу на должности старшего офицера направления, а с марта 1994 года — начальника группы подготовки командующего береговыми войсками ВМФ. С февраля 1995 года проходил службу на должности старшего офицера-оператора 1 направления 2 управления Главного оперативного управления Генерального штаба.

1997-1999 годы — слушатель Военной академии Генерального штаба Вооруженных Сил Российской Федерации.

С августа 1999года проходил службу на должностях старшего офицера-оператора, с января 2000 года — начальника группы, с сентября 2001 года, -заместителя начальника направления, с октября 2003 года — начальника 2 направления 5 управления Главного оперативного управления Генерального штаба.

Воинское звание «генерал-майор» присвоено Указом Президента РФ № 1540 от 12 декабря 2004 года.

В настоящее время — Первый заместитель Председателя Всероссийской общественной организации морских пехотинцев «Тайфун».

Государственные награды: ордена «За службу Родине в Вооруженных силах СССР» III степени (1990 год), «За военные заслуги» (1995 год), 15 медалей. Женат. Имеет двух сыновей – офицеры.

Генерал-майор Гордеев Алексей Николаевич

Гордеев Алексей Николаевич родился 29 апреля 1953г

после окончания Алма-Атинского высшего общевойскового командного училища в Группе советских войск в Германии служил командиром разведывательного взвода на мотоциклах, затем — командиром разведроты.

Далее — перевод на Дальний Восток ротным разведки и выше — начальником штаба разведбата. Потом назначили командиром мотострелкового батальона, который по боевой подготовке стал лучшим в округе и серебряным призером на состязаниях в масштабе Сухопутных войск Вооруженных Сил СССР.

С Дальнего Востока Алексей Гордеев шагнул в академию имени М.В. Фрунзе, после которой его назначили начштаба полка в Калининграде. Затем Афган. После вывода 40-й армии возвратился в Прибалтику.

Был начальником штаба полка в Клайпеде. Потом в Литве командиром мотострелкового полка в мотострелковой дивизии, которую впоследствии передали Военно-морскому флоту и в 1989-м году преобразовали в дивизию береговой обороны.

Понятное дело, всех тут же переодели в морпеховскую форму. Стал начальником штаба дивизии, а в 1993-м ее расформировали. И 10 декабря того же года полковник Алексей Гордеев прибыл на Северный флот заместителем начальника береговых войск СФ полковника Александра Отраковского, впоследствии — генерал-майора, Героя России, умершего в Чечне во время второй северокавказской кампании.

— Не жалею, что судьба свела с ВМФ, — говорит Алексей Николаевич.

— Вообще, сейчас так получилось, что половина моей службы принадлежит «сухопутью», а вторые четырнадцать лет — флоту. Уже на морпеховскую его долю выпали две чеченские кампании, в которых Гордеев непосредственно не участвовал, но, будучи замначальника береговых войск СФ, готовил людей для войны, используя для этого весь афганский боевой опыт. И парни уходили подготовленными: если автоматчик, то досконально знал возможности автомата и грамотно применял его на практике, если гранатометчик, то в совершенстве владел своим штатным оружием…

Вообще, по словам генерала, служба в морской пехоте наиболее памятна. Наверное, в первую очередь тем, что пришлась уже на зрелые годы. Занимался боевой подготовкой, участвовал во всех учениях заполярных «черных беретов»: будь то высадка морского десанта на необорудованное побережье, морская десантная подготовка или ракетная стрельба; в полевых выходах и лагерных сборах подразделений береговых войск СФ.

В настоящее время генерал – майор Гордеев Алексей Николаевич живёт в Москве и является президентом московской региональной общественной организации морских пехотинцев «Сатурн» города Москвы, член Центрального Совета Всеросийской Общественной Организации «ТАЙФУН» Пожелаем ему здоровья и долголетия.

гвардии генерал-майор Пушкин Сергей Витальевич

Родился в 1959 года в Костроме.

В 1984 году Закончил Казанское высшее танковое командное училище.

Проходил службу в Забайкальском военном округе и Группе советских войск в Германии.

После окончания в 1991 году Бронетанковой академии имени Р.Я. Малиновского получил назначение в бригаду морской пехоты Северного флота.

1996-2000г.г. командир 77-й отдельной гвардейской Московско-Черниговской ордена Ленина, Краснознамённой, ордена Суворова II степени бригады морской пехоты

2007-2009 г.г. командовал 55-й дивизией морской пехоты Тихоокеанского флота (предшественница нынешней 155-й отдельной бригады).

С 2009 года – начальник береговых войск ТОФ.

Принимал участие в боевых действиях на территории Северо-Кавказского региона.

Отмечен государственными наградами.

В 2010 году Закончил Военную Академию Генерального штаба Вооружённых сил Российской Федерации.

В 2014 году уволен в запас

имеет государственные награды;

- Прошёл профессиональную переподготовку в Московской академии государственного и муниципального управления при Президенте Российской Федерации.

- кадровым распоряжением Администрации города Костромы от 17 апреля 2015 назначен на должность начальника Управления городского пассажирского транспорта Администрации города Костромы.

| United States Marine Corps | |

|---|---|

Emblem of the United States Marine Corps |

|

| Founded | 11 July 1798 (225 years, 2 months) (as current service) 10 November 1775 |

| Country | |

| Type | Maritime land force |

| Size |

|

| Part of | United States Armed Forces Department of the Navy |

| Headquarters | The Pentagon Arlington County, Virginia, U.S. |

| Nickname(s) | «Jarheads», «Devil Dogs», «Teufel Hunden», «Leathernecks» |

| Motto(s) | Semper fidelis («Always faithful») |

| Colors | Scarlet and gold[6][7] |

| March | «Semper Fidelis» Playⓘ |

| Mascot(s) | English bulldog[8][9] |

| Anniversaries | 10 November |

| Equipment | List of U.S. Marine Corps equipment |

| Engagements |

See list

|

| Decorations | Presidential Unit Citation

|

| Website | Marines.mil |

| Commanders | |

| Commander-in-Chief | |

| Secretary of Defense | |

| Secretary of the Navy | |

| Commandant | |

| Assistant Commandant | |

| Sergeant Major of the Marine Corps | |

| Insignia | |

| Flag |  |

| Seal |  |

| Emblem («Eagle, Globe, and Anchor» or «EGA»)[note 1] |  |

| Wordmark | |

| Song | «The Marine’s Hymn» Playⓘ |

The United States Marine Corps (USMC), also referred to as the United States Marines, is the maritime land force service branch of the United States Armed Forces responsible for conducting expeditionary and amphibious operations[11] through combined arms, implementing its own infantry, artillery, aerial, and special operations forces. The U.S. Marine Corps is one of the eight uniformed services of the United States.

The Marine Corps has been part of the U.S. Department of the Navy since 30 June 1834 with its sister service, the United States Navy.[12] The USMC operates installations on land and aboard sea-going amphibious warfare ships around the world. Additionally, several of the Marines’ tactical aviation squadrons, primarily Marine Fighter Attack squadrons, are also embedded in Navy carrier air wings and operate from the aircraft carriers.[citation needed]

The history of the Marine Corps began when two battalions of Continental Marines were formed on 10 November 1775 in Philadelphia as a service branch of infantry troops capable of fighting both at sea and on shore.[13] In the Pacific theater of World War II, the Corps took the lead in a massive campaign of amphibious warfare, advancing from island to island.[14][15][16] As of 2022, the USMC has around 177,200 active duty members and some 32,400 personnel in reserve.[3]

Mission[edit]

As outlined in 10 U.S.C. § 5063 and as originally introduced under the National Security Act of 1947, three primary areas of responsibility for the U.S. Marine Corps are:

- Seizure or defense of advanced naval bases and other land operations to support naval campaigns;

- Development of tactics, technique, and equipment used by amphibious landing forces in coordination with the Army and Air Force; and

- Such other duties as the President or Department of Defense may direct.

This last clause derives from similar language in the Congressional acts «For the Better Organization of the Marine Corps» of 1834, and «Establishing and Organizing a Marine Corps» of 1798. In 1951, the House of Representatives’ Armed Services Committee called the clause «one of the most important statutory – and traditional – functions of the Marine Corps». It noted that the Corps has more often than not performed actions of a non-naval nature, including its famous actions in Tripoli, the War of 1812, Chapultepec, and numerous counterinsurgency and occupational duties (such as those in Central America, World War I, and the Korean War). While these actions are not accurately described as support of naval campaigns nor as amphibious warfare, their common thread is that they are of an expeditionary nature, using the mobility of the Navy to provide timely intervention in foreign affairs on behalf of American interests.[17]

The Marine Band, dubbed the «President’s Own» by Thomas Jefferson, provides music for state functions at the White House.[18] Marines from Ceremonial Companies A & B, quartered in Marine Barracks, Washington, D.C., guard presidential retreats, including Camp David, and the marines of the Executive Flight Detachment of HMX-1 provide helicopter transport to the President and Vice President, with the radio call signs «Marine One» and «Marine Two», respectively.[19] The Executive Flight Detachment also provides helicopter transport to Cabinet members and other VIPs. By authority of the 1946 Foreign Service Act, the Marine Security Guards of the Marine Embassy Security Command provide security for American embassies, legations, and consulates at more than 140 posts worldwide.[20]

The relationship between the Department of State and the U.S. Marine Corps is nearly as old as the Corps itself. For over 200 years, marines have served at the request of various Secretaries of State. After World War II, an alert, disciplined force was needed to protect American embassies, consulates, and legations throughout the world. In 1947, a proposal was made that the Department of Defense furnishes Marine Corps personnel for Foreign Service guard duty under the provisions of the Foreign Service Act of 1946. A formal Memorandum of Agreement was signed between the Department of State and the Secretary of the Navy on 15 December 1948, and 83 marines were deployed to overseas missions. During the first year of the program, 36 detachments were deployed worldwide.[21]

Historical mission[edit]

The Marine Corps was founded to serve as an infantry unit aboard naval vessels and was responsible for the security of the ship and its crew by conducting offensive and defensive combat during boarding actions and defending the ship’s officers from mutiny; to the latter end, their quarters on the ship were often strategically positioned between the officers’ quarters and the rest of the vessel. Continental Marines manned raiding parties, both at sea and ashore. America’s first amphibious assault landing occurred early in the Revolutionary War on 3 March 1776 as the Marines gained control of Fort Montagu and Fort Nassau, a British ammunition depot and naval port in New Providence, the Bahamas. The role of the Marine Corps has expanded significantly since then; as the importance of its original naval mission declined with changing naval warfare doctrine and the professionalization of the naval service, the Corps adapted by focusing on formerly secondary missions ashore. The Advanced Base Doctrine of the early 20th century codified their combat duties ashore, outlining the use of marines in the seizure of bases and other duties on land to support naval campaigns.

Throughout the late 19th and 20th centuries, Marine detachments served aboard Navy cruisers, battleships and aircraft carriers. Marine detachments served in their traditional duties as a ship’s landing force, manning the ship’s weapons and providing shipboard security. Marine detachments were augmented by members of the ship’s company for landing parties, such as in the First Sumatran expedition of 1832, and continuing in the Caribbean and Mexican campaigns of the early 20th centuries. Marines developed tactics and techniques of amphibious assault on defended coastlines in time for use in World War II.[22] During World War II, marines continued to serve on capital ships. They often were assigned to man anti-aircraft batteries.[citation needed]

In 1950,[23] President Harry Truman responded to a message from U.S. Representative Gordon L. McDonough. McDonough had urged President Truman to add Marine representation on the Joint Chiefs of Staff. President Truman, writing in a letter addressed to McDonough, stated that «The Marine Corps is the Navy’s police force and as long as I am President that is what it will remain. They have a propaganda machine that is almost equal to Stalin’s.» McDonough then inserted President Truman’s letter, dated 29 August 1950, into the Congressional Record. Congressmen and Marine organizations reacted, calling President Truman’s remarks an insult and demanded an apology. Truman apologized to the Marine commandant at the time, writing, «I sincerely regret the unfortunate choice of language which I used in my letter of August 29 to Congressman McDonough concerning the Marine Corps.» While Truman had apologized for his metaphor, he did not alter his position that the Marine Corps should continue to report to the Navy secretary. He made amends only by making a surprise visit to the Marine Corps League a few days later, when he reiterated, «When I make a mistake, I try to correct it. I try to make as few as possible.» He received a standing ovation.[24]

When gun cruisers were retired by the 1960s, the remaining Marine detachments were only seen on battleships and carriers. Its original mission of providing shipboard security ended in the 1990s.[citation needed]

Capabilities[edit]

The Marine Corps fulfills a critical military role as an amphibious warfare force. It is capable of asymmetric warfare with conventional, irregular, and hybrid forces. While the Marine Corps does not employ any unique capabilities, as a force it can rapidly deploy a combined-arms task force to almost anywhere in the world within days. The basic structure for all deployed units is a Marine Air-Ground Task Force (MAGTF) that integrates a ground combat element, an aviation combat element and a logistics combat element under a common command element. While the creation of joint commands under the Goldwater–Nichols Act has improved interservice coordination between each branch, the Corps’s ability to permanently maintain integrated multielement task forces under a single command provides a smoother implementation of combined-arms warfare principles.[25]

The close integration of disparate Marine units stems from an organizational culture centered on the infantry. Every other Marine capability exists to support the infantry. Unlike some Western militaries, the Corps remained conservative against theories proclaiming the ability of new weapons to win wars independently. For example, Marine aviation has always been focused on close air support and has remained largely uninfluenced by air power theories proclaiming that strategic bombing can single-handedly win wars.[22]

This focus on the infantry is matched with the doctrine of «Every marine [is] a rifleman», a precept of Commandant Alfred M. Gray, Jr., emphasizing the infantry combat abilities of every marine. All marines, regardless of military specialization, receive training as a rifleman; and all officers receive additional training as infantry platoon commanders.[26] During World War II at the Battle of Wake Island, when all of the Marine aircraft were destroyed, pilots continued the fight as ground officers, leading supply clerks and cooks in a final defensive effort.[27] Flexibility of execution is implemented via an emphasis on «commander’s intent» as a guiding principle for carrying out orders, specifying the end state but leaving open the method of execution.[28]

The amphibious assault techniques developed for World War II evolved, with the addition of air assault and maneuver warfare doctrine, into the current «Operational Maneuver from the Sea» doctrine of power projection from the seas.[11] The Marines are credited with the development of helicopter insertion doctrine and were the earliest in the American military to widely adopt maneuver-warfare principles, which emphasize low-level initiative and flexible execution. In light of recent warfare that has strayed from the Corps’s traditional missions,[29] the Marines have renewed an emphasis on amphibious capabilities.[30]

The Marine Corps relies on the Navy for sealift to provide its rapid deployment capabilities. In addition to basing a third of the Fleet Marine Force in Japan, Marine expeditionary units (MEU) are typically stationed at sea so they can function as first responders to international incidents.[31] To aid rapid deployment, the Maritime Pre-Positioning System was developed: fleets of container ships are positioned throughout the world with enough equipment and supplies for a marine expeditionary force to deploy for 30 days.[citation needed]

Doctrine[edit]

Two small manuals published during the 1930s established USMC doctrine in two areas. The Small Wars Manual laid the framework for Marine counter-insurgency operations from Vietnam to Iraq and Afghanistan while the Tentative Landing Operations Manual established the doctrine for the amphibious operations of World War II. «Operational Maneuver from the Sea» was the doctrine of power projection in 2006.[11]

History[edit]

Foundation and American Revolutionary War[edit]

The United States Marine Corps traces its roots to the Continental Marines of the American Revolutionary War, formed by Captain Samuel Nicholas by a resolution of the Second Continental Congress on 10 November 1775, to raise two battalions of marines. This date is celebrated as the birthday of the Marine Corps. Nicholas was nominated to lead the Marines by John Adams.[32] By December 1775, Nicholas raised one battalion of 300 men by recruitment in his home city of Philadelphia.[citation needed]

In January 1776, the Marines went to sea under the command of Commodore Esek Hopkins and in March undertook their first amphibious landing, the Battle of Nassau in the Bahamas, occupying the British port of Nassau for two weeks.[33] On 3 January 1777, the Marines arrived at the Battle of Princeton attached to General John Cadwalader’s brigade, where they had been assigned by General George Washington; by December 1776, Washington was retreating through New Jersey and, needing veteran soldiers, ordered Nicholas and the Marines to attach themselves to the Continental Army. The Battle of Princeton, where the Marines along with Cadwalader’s brigade were personally rallied by Washington, was the first land combat engagement of the Marines; an estimated 130 marines were present at the battle.[33]

At the end of the American Revolution, both the Continental Navy and Continental Marines were disbanded in April 1783. The institution was resurrected on 11 July 1798; in preparation for the Quasi-War with France, Congress created the United States Marine Corps.[34] Marines had been enlisted by the War Department as early as August 1797[35][better source needed] for service in the newly-built frigates authorized by the Congressional «Act to provide a Naval Armament» of 18 March 1794,[36][better source needed] which specified the numbers of marines to recruit for each frigate.[37]

The Marines’ most famous action of this period occurred during the First Barbary War (1801–1805) against the Barbary pirates,[38] when William Eaton and First Lieutenant Presley O’Bannon led 8 marines and 500 mercenaries in an effort to capture Tripoli. Though they only reached Derna, the action at Tripoli has been immortalized in the Marines’ Hymn and the Mameluke sword carried by Marine officers.[39]

War of 1812 and afterward[edit]

During the War of 1812, Marine detachments on Navy ships took part in some of the great frigate duels that characterized the war, which were the first and last engagements of the conflict. Their most significant contribution was holding the center of General Andrew Jackson’s defensive line at the 1815 Battle of New Orleans, the final major battle and one of the most one-sided engagements of the war. With widespread news of the battle and the capture of HMS Cyane, HMS Levant and HMS Penguin, the final engagements between British and U.S. forces, the Marines had gained a reputation as expert marksmen, especially in defensive and ship-to-ship actions.[39] They played a large role in the 1813 defense of Sacket’s Harbor, New York and Norfolk and Portsmouth, Virginia,[40] also taking part in the 1814 defense of Plattsburgh in the Champlain Valley during one of the final British offensives along the Canadian-U.S. border. The Battle of Bladensburg, fought 24 August 1814, was one of the worst days for American arms, though a few units and individuals performed heroic service. Notable among them were Commodore Joshua Barney’s 500 sailors and the 120 marines under Captain Samuel Miller USMC, who inflicted the bulk of British casualties and were the only effective American resistance during the battle. A final desperate Marine counter attack, with the fighting at close quarters, however was not enough; Barney and Miller’s forces were overrun. In all of 114 marines, 11 were killed and 16 wounded. During the battle Captain Miller’s arm was badly wounded, for his gallant service in action, Miller was brevetted to the rank of Major USMC.[41]

After the war, the Marine Corps fell into a malaise that ended with the appointment of Archibald Henderson as its fifth commandant in 1820. Under his tenure, the Corps took on expeditionary duties in the Caribbean, the Gulf of Mexico, Key West, West Africa, the Falkland Islands, and Sumatra. Commandant Henderson is credited with thwarting President Jackson’s attempts to combine and integrate the Marine Corps with the Army.[39] Instead, Congress passed the Act for the Better Organization of the Marine Corps in 1834, stipulating that the Corps was part of the Department of the Navy as a sister service to the Navy.[42] This would be the first of many times that the independent existence of the Corps was challenged.[citation needed]

Commandant Henderson volunteered the Marines for service in the Seminole Wars of 1835, personally leading nearly half of the entire Corps (two battalions) to war. A decade later, in the Mexican–American War (1846–1848), the Marines made their famed assault on Chapultepec Palace in Mexico City, which would be later celebrated as the «Halls of Montezuma» in the Marines’ Hymn. In fairness to the U.S. Army, most of the troops who made the final assault at the Halls of Montezuma were soldiers and not marines.[43] The Americans forces were led by Army General Winfield Scott. Scott organized two storming parties of about 250 men each for 500 men total including 40 marines.[citation needed]

In the 1850s, the Marines engaged in service in Panama and Asia and were attached to Commodore Matthew Perry’s East India Squadron on its historic trip to the Far East.[44]

American Civil War to World War I[edit]

The Marine Corps played a small role in the Civil War (1861–1865); their most prominent task was blockade duty. As more and more states seceded from the Union, about a third of the Corps’s officers left the United States to join the Confederacy and form the Confederate States Marine Corps, which ultimately played little part in the war. The battalion of recruits formed for the First Battle of Bull Run performed poorly, retreating with the rest of the Union forces.[31] Blockade duty included sea-based amphibious operations to secure forward bases. In late November 1861, Marines and sailors landed a reconnaissance in force from USS Flag at Tybee Island, Georgia, to occupy the lighthouse and Martello tower on the northern end of the island. It would later be the Army base for bombardment of Fort Pulaski.[45] In April and May 1862, Marines participated in the capture and occupation of New Orleans and the occupation of Baton Rouge, Louisiana,[46] key events in the war that helped secure Union control of the lower Mississippi River basin and denied the Confederacy a major port and naval base on the Gulf Coast.[citation needed]

The remainder of the 19th century was marked by declining strength and introspection about the mission of the Marine Corps. The Navy’s transition from sail to steam put into question the need for Marines on naval ships. Meanwhile, Marines served as a convenient resource for interventions and landings to protect American interests overseas. The Corps was involved in over 28 separate interventions in the 30 years from the end of the American Civil War to the end of the 19th century.[47] They were called upon to stem political and labor unrest within the United States.[48] Under Commandant Jacob Zeilin’s tenure, Marine customs and traditions took shape: the Corps adopted the Marine Corps emblem on 19 November 1868. It was during this time that «The Marines’ Hymn» was first heard. Around 1883, the Marines adopted their current motto «Semper fidelis» (Always Faithful).[39] John Philip Sousa, the musician and composer, enlisted as a Marine apprentice at age 13, serving from 1867 until 1872, and again from 1880 to 1892 as the leader of the Marine Band.[citation needed]

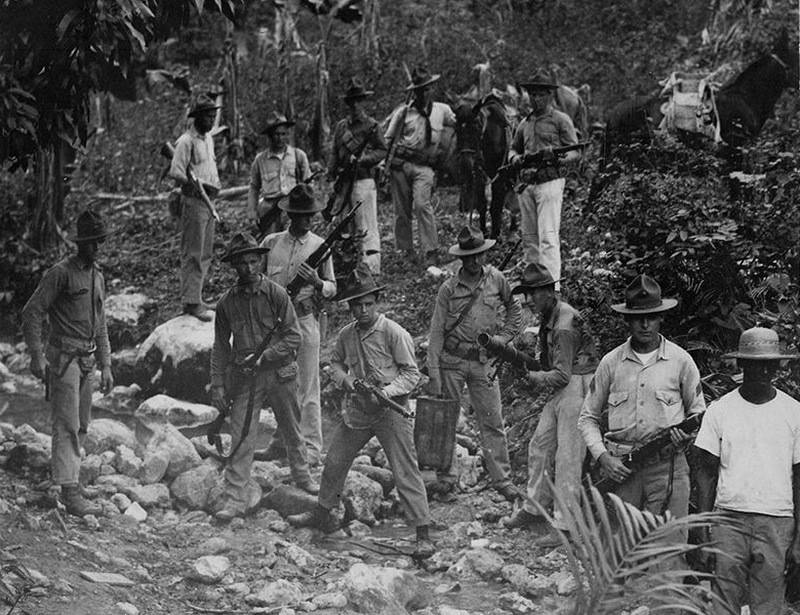

During the Spanish–American War (1898), Marines led American forces ashore in the Philippines, Cuba, and Puerto Rico, demonstrating their readiness for deployment. At Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, the Marines seized an advanced naval base that remains in use today. Between 1899 and 1916, the Corps continued its record of participation in foreign expeditions, including the Philippine–American War, the Boxer Rebellion in China, Panama, the Cuban Pacifications, the Perdicaris incident in Morocco, Veracruz, Santo Domingo, and the Banana Wars in Haiti and Nicaragua;[citation needed] the experiences gained in counterinsurgency and guerrilla operations during this period were consolidated into the Small Wars Manual.[49][better source needed]

World War I[edit]

During World War I, Marines served as a part of the American Expeditionary Force under General John J. Pershing when America entered into the war on 6 April 1917. The Marine Corps had a deep pool of officers and non-commissioned officers with battle experience and thus experienced a large expansion. The U.S. Marine Corps entered the war with 511 officers and 13,214 enlisted personnel and by 11 November 1918 had reached a strength of 2,400 officers and 70,000 enlisted.[50] African-Americans were entirely excluded from the Marine Corps during this conflict.[51] Opha May Johnson was the first woman to enlist in the Marines; she joined the Marine Corps Reserve in 1918 during World War I, officially becoming the first female Marine.[52] From then until the end of World War I, 305 women enlisted in the Corps.[53] During the Battle of Belleau Wood in 1918, the Marines and U.S. media reported that Germans had nicknamed them Teufel Hunden, meaning «Devil Dogs» for their reputation as shock troops and marksmen at ranges up to 900 meters; there is no evidence of this in German records (as Teufelshunde would be the proper German phrase). Nevertheless, the name stuck in U.S. Marine lore.[54]

Between the World Wars, the Marine Corps was headed by Commandant John A. Lejeune, and under his leadership, the Corps studied and developed amphibious techniques that would be of great use in World War II. Many officers, including Lieutenant Colonel Earl Hancock «Pete» Ellis, foresaw a war in the Pacific with Japan and undertook preparations for such a conflict. Through 1941, as the prospect of war grew, the Corps pushed urgently for joint amphibious exercises with the Army and acquired amphibious equipment that would prove of great use in the upcoming conflict.[55]

World War II[edit]

In World War II, the Marines performed a central role in the Pacific War, along with the U.S. Army. The battles of Guadalcanal, Bougainville, Tarawa, Guam, Tinian, Cape Gloucester, Saipan, Peleliu, Iwo Jima, and Okinawa saw fierce fighting between marines and the Imperial Japanese Army. Some 600,000 Americans served in the U.S. Marine Corps in World War II.[56]

The Battle of Iwo Jima, which began on 19 February 1945, was arguably the most famous Marine engagement of the war. The Japanese had learned from their defeats in the Marianas Campaign and prepared many fortified positions on the island including pillboxes and network of tunnels. The Japanese put up fierce resistance, but American forces reached the summit of Mount Suribachi on 23 February. The mission was accomplished with high losses of 26,000 American casualties and 22,000 Japanese.[57]

The Marines played a comparatively minor role in the European theater. Nonetheless, they did continue to provide security detachments to U.S. embassies and ships, contributed personnel to small special ops teams dropped into Nazi-occupied Europe as part of Office of Strategic Services (OSS, the precursor to the CIA) missions, and acted as staff planners and trainers for U.S. Army amphibious operations, including the Normandy landings.[58][59] By the end of the war, the Corps had expanded from two brigades to six divisions, five air wings, and supporting troops, totaling about 485,000 marines. In addition, 20 defense battalions and a parachute battalion were raised.[60] Nearly 87,000 marines were casualties during World War II (including nearly 20,000 killed), and 82 were awarded the Medal of Honor.[61]

In 1942, the Navy Seabees were created with the Marine Corps providing their organization and military training. Many Seabee units were issued the USMC standard issue and were re-designated «Marine». Despite the Corps giving them their military organization and military training, issuing them uniforms, and redesignating their units, the Seabees remained Navy.[note 2][62][63] USMC historian Gordon L. Rottmann writes that one of the «Navy’s biggest contributions to the Marine Corps during WWII was the creation of the Seabees.»[64]

Despite Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal’s prediction that the Marine flag raising at Iwo Jima meant «a Marine Corps for the next five hundred years»,[65][66] the Corps faced an immediate institutional crisis following the war because of a suddenly shrunken budget. Army generals pushing for a strengthened and reorganized defense establishment attempted to fold the Marine mission and assets into the Navy and Army. Drawing on hastily assembled Congressional support, and with the assistance of the so-called «Revolt of the Admirals», the Marine Corps rebuffed such efforts to dismantle the Corps, resulting in statutory protection of the Marine Corps in the National Security Act of 1947.[67] Shortly afterward, in 1952 the Douglas–Mansfield Act afforded the commandant an equal voice with the Joint Chiefs of Staff on matters relating to the Marines and established the structure of three active divisions and air wings that remain today.[citation needed]

Korean War[edit]

The beginning of the Korean War (1950–1953) saw the hastily formed Provisional Marine Brigade holding the defensive line at the Pusan Perimeter. To execute a flanking maneuver, General Douglas MacArthur called on United Nations forces, including U.S. marines, to make an amphibious landing at Inchon. The successful landing resulted in the collapse of North Korean lines and the pursuit of North Korean forces north near the Yalu River until the entrance of the People’s Republic of China into the war. Chinese troops surrounded, surprised, and overwhelmed the overextended and outnumbered American forces. The U.S. Army’s X Corps, which included the 1st Marine Division and the Army’s 7th Infantry Division regrouped and inflicted heavy casualties during their fighting withdrawal to the coast, known as the Battle of Chosin Reservoir.

The fighting calmed after the Battle of the Chosin Reservoir, but late in March 1953, the relative quiet of the war was broken when the People’s Liberation Army launched a massive offensive on three outposts manned by the 5th Marine Regiment. These outposts were codenamed «Reno», «Vegas», and «Carson». The campaign was collectively known as the Nevada Cities Campaign. There was brutal fighting on Reno hill, which was eventually captured by the Chinese. Although Reno was lost, the 5th Marines held both Vegas and Carson through the rest of the campaign. In this one campaign, the Marines suffered approximately 1,000 casualties and might have suffered much more without the U.S. Army’s Task Force Faith. Marines would continue a battle of attrition around the 38th Parallel until the 1953 armistice.[68] During the war, the Corps expanded from 75,000 regulars to a force of 261,000 marines, mostly reservists; 30,544 marines were killed or wounded during the war, and 42 were awarded the Medal of Honor.[69]

Vietnam War[edit]

The Marine Corps served in the Vietnam War, taking part in such battles as the Battle of Hue and the Battle of Khe Sanh in 1968. Individuals from the USMC generally operated in the Northern I Corps Regions of South Vietnam. While there, they were constantly engaged in a guerrilla war against the Viet Cong, along with an intermittent conventional war against the North Vietnamese Army, this made the Marine Corps known throughout Vietnam and gained a frightening reputation from the Viet Cong. Portions of the Corps were responsible for the less-known Combined Action Program that implemented unconventional techniques for counterinsurgency and worked as military advisors to the Republic of Vietnam Marine Corps. Marines were withdrawn in 1971 and returned briefly in 1975 to evacuate Saigon and attempt a rescue of the crew of the SS Mayaguez.[70] Vietnam was the longest war up to that time for the Marines; by its end, 13,091 had been killed in action,[71][72] 51,392 had been wounded, and 57 Medals of Honor had been awarded.[73][74] Because of policies concerning rotation, more marines were deployed for service during Vietnam than World War II.[75]

While recovering from Vietnam, the Corps hit a detrimental low point in its service history caused by courts-martial and non-judicial punishments related partially to increased unauthorized absences and desertions during the war. Overhaul of the Corps began in the late 1970s, discharging the most delinquent, and once the quality of new recruits improved, the Corps focused on reforming the non-commissioned officer Corps, a vital functioning part of its forces.[25]

Interim: Vietnam War to the War on Terror[edit]

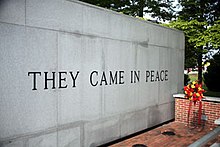

After the Vietnam War, the U.S. Marines resumed their expeditionary role, participating in the failed 1980 Iran hostage rescue attempt Operation Eagle Claw, the Operation Urgent Fury and the Operation Just Cause. On 23 October 1983, the Marine barracks in Beirut was bombed, causing the highest peacetime losses to the Corps in its history (220 marines and 21 other service members were killed) and leading to the American withdrawal from Lebanon. In 1990, marines of the Joint Task Force Sharp Edge saved thousands of lives by evacuating British, French and American nationals from the violence of the Liberian Civil War.

During the Persian Gulf War of 1990 to 1991, Marine task forces formed for Operation Desert Shield and later liberated Kuwait, along with Coalition forces, in Operation Desert Storm.[39] Marines participated in combat operations in Somalia (1992–1995) during Operations Restore Hope, Restore Hope II, and United Shield to provide humanitarian relief.[76] In 1997, marines took part in Operation Silver Wake, the evacuation of American citizens from the U.S. Embassy in Tirana, Albania.[citation needed]

Global War on Terrorism[edit]

Following the attacks on 11 September 2001, President George W. Bush announced the Global War on Terrorism. The stated objective of the Global War on Terror is «the defeat of Al-Qaeda, other terrorist groups and any nation that supports or harbors terrorists».[77] Since then, the Marine Corps, alongside the other military services, has engaged in global operations around the world in support of that mission.[citation needed]

In spring 2009, President Barack Obama’s goal of reducing spending in the Defense Department was led by Secretary Robert Gates in a series of budget cuts that did not significantly change the Corps’s budget and programs, cutting only the VH-71 Kestrel and resetting the VXX program.[78][79][80] However, the National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform singled the Corps out for the brunt of a series of recommended cuts in late 2010.[81] In light of budget sequestration in 2013, General James Amos set a goal of a force of 174,000 Marines.[82] He testified that this was the minimum number that would allow for an effective response to even a single contingency operation, but it would reduce the peacetime ratio of time at home bases to time deployed down to a historical low level.[83]

Afghanistan Campaign[edit]

Marines and other American forces began staging in Pakistan and Uzbekistan on the border of Afghanistan as early as October 2001 in preparation for Operation Enduring Freedom.[84] The 15th and 26th Marine Expeditionary Units were some of the first conventional forces into Afghanistan in support of Operation Enduring Freedom in November 2001.[85]

After that, Marine battalions and squadrons rotated through, engaging Taliban and Al-Qaeda forces. Marines of the 24th Marine Expeditionary Unit flooded into the Taliban-held town of Garmsir in Helmand Province on 29 April 2008, in the first major American operation in the region in years.[86] In June 2009, 7,000 marines with the 2nd Marine Expeditionary Brigade (2nd MEB) deployed to Afghanistan in an effort to improve security[87] and began Operation Strike of the Sword the next month. In February 2010, the 2nd MEB launched the largest offensive of the Afghan Campaign since 2001, the Battle of Marjah, to clear the Taliban from their key stronghold in Helmand Province.[88] After Marjah, marines progressed north up the Helmand River and cleared the towns of Kajahki and Sangin. Marines remained in Helmand Province until 2014.[89]

Iraq Campaign[edit]

U.S. Marines served in the Iraq War, along with its sister services. The I Marine Expeditionary Force, along with the U.S. Army’s 3rd Infantry Division, spearheaded the 2003 invasion of Iraq.[90] The Marines left Iraq in the summer of 2003 but returned in the beginning of 2004. They were given responsibility for the Al Anbar Province, the large desert region to the west of Baghdad. During this occupation, the Marines lead assaults on the city of Fallujah in April (Operation Vigilant Resolve) and November 2004 (Operation Phantom Fury) and saw intense fighting in such places as Ramadi, Al-Qa’im and Hīt.[91] The service’s time in Iraq courted controversy with events such as the Haditha killings and the Hamdania incident.[92][93] The Anbar Awakening and 2007 surge reduced levels of violence. The Marine Corps officially ended its role in Iraq on 23 January 2010 when it handed over responsibility for Al Anbar Province to the U.S. Army.[94] Marines returned to Iraq in the summer of 2014 in response to growing violence there.[95]

Operations in Africa[edit]

Throughout the Global War on Terrorism, the U.S. Marines have supported operations in Africa to counter Islamic extremism and piracy in the Red Sea. In late 2002, Combined Joint Task Force – Horn of Africa was stood up at Camp Lemonnier, Djibouti to provide regional security.[96] Despite transferring overall command to the Navy in 2006, the Marines continued to operate in the Horn of Africa into 2007.[97]

Organization[edit]

Department of the Navy[edit]

The Department of the Navy, led by the Secretary of the Navy, is a military department of the cabinet-level U.S. Department of Defense that oversees the Marine Corps and the Navy. The most senior Marine officer is the Commandant (unless a Marine officer is the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs or Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs), responsible to the Secretary of the Navy for organizing, recruiting, training, and equipping the Marine Corps so that its forces are ready for deployment under the operational command of the combatant commanders. The Marine Corps is organized into four principal subdivisions: Headquarters Marine Corps (HQMC), the Operating Forces, the Supporting Establishment, and the Marine Forces Reserve (MARFORRES or USMCR).[citation needed]

Headquarters Marine Corps[edit]

Headquarters Marine Corps (HQMC) consists of the Commandant of the Marine Corps, the Assistant Commandant of the Marine Corps, the Director Marine Corps Staff, the several Deputy Commandants, the Sergeant Major of the Marine Corps, and various special staff officers and Marine Corps agency heads that report directly to either the Commandant or Assistant Commandant. HQMC is supported by the Headquarters and Service Battalion, USMC providing administrative, supply, logistics, training, and services support to the Commandant and his staff.[citation needed]

Operating Forces[edit]

The Operating Forces are divided into three categories: Marine Corps Forces (MARFOR) assigned to unified combatant commands, namely, the Fleet Marine Forces (FMF); Security Forces guarding high-risk naval installations; and Security Guard detachments at American embassies. Under the «Forces for Unified Commands» memo, in accordance with the Unified Command Plan, Marine Corps Forces are assigned to each of the combatant commands at the discretion of the secretary of defense. Since 1991, the Marine Corps has maintained component headquarters at each of the regional unified combatant commands.[98]

Marine Corps Forces are divided into Forces Command (MARFORCOM) and Pacific Command (MARFORPAC), each headed by a lieutenant general dual-posted as the commanding general of either FMF Atlantic (FMFLANT) or FMF Pacific (FMFPAC), respectively. MARFORCOM/FMFLANT has operational control of the II Marine Expeditionary Force; MARFORPAC/FMFPAC has operational control of the I Marine Expeditionary Force and III Marine Expeditionary Force.[31]

Marine Air-Ground Task Force[edit]

The basic framework for deployable Marine units is the Marine Air-Ground Task Force (MAGTF), a flexible structure of varying size. A MAGTF integrates a ground combat element (GCE), an aviation combat element (ACE), and a logistics combat element (LCE) under a common command element (CE), capable of operating independently or as part of a larger coalition. The MAGTF structure reflects a strong preference in the Corps toward self-sufficiency and a commitment to combined arms, both essential assets to an expeditionary force. The Marine Corps has a wariness and distrust of reliance on its sister services and towards joint operations in general.[25]

Supporting Establishment[edit]

The Supporting Establishment includes the Combat Development Command, the Logistics Command, the Systems Command, the Recruiting Command, the Installations Command, the Marine Band, and the Marine Drum and Bugle Corps.[citation needed]

Marine Corps bases and stations[edit]

The Marine Corps operates many major bases, 14 of which host operating forces, 7 support and training installations, as well as satellite facilities.[99] Marine Corps bases are concentrated around the locations of the Marine Expeditionary Forces, though reserve units are scattered throughout the United States.

The principal bases are Camp Pendleton on the West Coast, home to I Marine Expeditionary Force;[citation needed] Camp Lejeune on the East Coast, home to II Marine Expeditionary Force;[citation needed] and Camp Butler in Okinawa, Japan, home to III Marine Expeditionary Force.[citation needed]

Other important bases include air stations, recruit depots, logistics bases, and training commands. Marine Corps Air Ground Combat Center Twentynine Palms in California is the Marine Corps’s largest base and home to the Corps’s most complex combined-arms live-fire training.[citation needed] Marine Corps Base Quantico in Virginia is home to Marine Corps Combat Development Command and nicknamed the «Crossroads of the Marine Corps».[100][101]

The Marine Corps maintains a significant presence in the National Capital Region, with Headquarters Marine Corps scattered amongst the Pentagon, Henderson Hall, Washington Navy Yard, and Marine Barracks, Washington, D.C. Additionally, Marines operate detachments at many installations owned by other branches to better share resources, such as specialty schools. Marines are also present at and operate many forward bases during expeditionary operations.[citation needed]

Marine Forces Reserve[edit]

Marine Forces Reserve (MARFORRES/USMCR) consists of the Force Headquarters Group, 4th Marine Division, 4th Marine Aircraft Wing, and the 4th Marine Logistics Group. The MARFORRES/USMCR is capable of forming a 4th Marine Expeditionary Force or reinforcing/augmenting active-duty forces.[citation needed]

Special Operations[edit]

Marine Forces Special Operations Command (MARSOC) includes the Marine Raider Regiment, the Marine Raider Support Group, and the Marine Raider Training Center (MRTC). Both the Raider Regiment and the Raider Support Group consist of a headquarters company and three operations battalions. MRTC conducts screening, assessment, selection, training and development functions for MARSOC units. Marine Corps Special Operations Capable forces include: Air Naval Gunfire Liaison Companies, the Chemical Biological Incident Response Force, the Marine Division Reconnaissance Battalions, Force Reconnaissance Companies, Maritime Special Purpose Force, and Special Reaction Teams. Additionally, all deployed MEUs are certified as «special operations capable», namely, «MEU(SOC)».

Although the notion of a Marine special operations forces contribution to the United States Special Operations Command (USSOCOM) was considered as early as the founding of USSOCOM in the 1980s, it was resisted by the Marine Corps. Commandant Paul X. Kelley expressed the belief that marines should only support marines and that the Corps should not fund a special operations capability that would not directly support Marine Corps operations.[102] However, much of the resistance from within the Corps dissipated when Marine leaders watched the Corps’ 15th and 26th MEU(SOC)s «sit on the sidelines» during the very early stages of Operation Enduring Freedom while other conventional units and special operations units from the Army, Navy, and Air Force actively engaged in operations in Afghanistan.[103] After a three-year development period, the Corps agreed in 2006 to supply a 2,500-strong unit, Marine Forces Special Operations Command, which would answer directly to USSOCOM.[104]

Personnel[edit]

Leadership[edit]

The Commandant of the Marine Corps is the highest-ranking officer of the Marine Corps, unless a marine is either the chairman or vice chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. The commandant has the U.S. Code Title 10 responsibility to staff, train, and equip the Marine Corps and has no command authority. The commandant is a member of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and reports to the Secretary of the Navy.[105]

The Assistant Commandant of the Marine Corps acts as the chief deputy to the commandant. The Sergeant Major of the Marine Corps is the senior enlisted marine and acts as an adviser to the commandant. Headquarters Marine Corps comprises the rest of the commandant’s counsel and staff, with deputy commandants that oversee various aspects of the Corps assets and capabilities. The 39th and current Commandant is Eric M. Smith, while the 20th and current Sergeant Major is Carlos A. Ruiz.[106]

Women[edit]

Women have served in the United States Marine Corps since 1918.[107] The first woman to have enlisted was Opha May Johnson (1878–1955).[108][109] In January 2017, three women joined an infantry battalion at Camp Lejeune. Women had not served as infantry marines prior to this.[110] In 2017, the Marines released a recruitment advertisement that focused on women for the first time.[111] As of October 2019, female Marines make up 7.8% of the personnel.[citation needed]

In December 2020, the Marine Corps began a trial program to have females integrated into the training companies at their recruit depot in San Diego as Congress has mandated an end to the male-only program there. For the 60 female recruits, scheduled to begin training in San Diego in February 2021, the Corps will transfer female drill instructors from their recruit depot in Parris Island, which already has a coed program.[112] Fifty-three of these recruits successfully graduated from boot camp in April 2021 and became marines.[113][114]

Minorities[edit]

In 1776 and 1777, a dozen African American marines served in the American Revolutionary War, but from 1798 to 1942, the Marine Corps followed a racially discriminatory policy of denying African Americans the opportunity to serve.[115] The Marine Corps was the last of the services to recruit African Americans, and its own history page acknowledges that it was a presidential order that «forced the Corps, despite objections from its leadership, to begin recruiting African American Marines in 1942.[116] It accepted them as recruits into segregated all-black units.[115] For the next few decades, the incorporation of black troops was not widely accepted within the Corps, nor was desegregation smoothly or quickly achieved. The integration of non-white Marine Corps personnel proceeded in stages from segregated battalions in 1942, to unified training in 1949, and finally full integration in 1960.[117]

Today the Marine Corps is a desegregated force, made up of marines of all races working and fighting alongside each other. As of 2020, African Americans are currently underrepresented in the Marine Corps as compared to their overall percentage of the U.S. population. Concurrently, the Marine Corps is the only service where Hispanics are overrepresented per the same metric.[118]

Rank structure[edit]

As in the rest of the United States Armed Forces (excluding the Air Force and Space Force, which do not currently appoint warrant officers), Marine Corps ranks fall into one of three categories: commissioned officer, warrant officer, and enlisted, in decreasing order of authority. To standardize compensation, each rank is assigned a pay grade.[119]

Commissioned officers[edit]

Commissioned officers are distinguished from other officers by their commission, which is the formal written authority, issued in the name of the President of the United States, that confers the rank and authority of a Marine officer. Commissioned officers carry the «special trust and confidence» of the President of the United States.[17] Marine Corps commissioned officers are promoted based on an «up or out» system in accordance with the Defense Officer Personnel Management Act of 1980.[120]

Warrant officers[edit]

Warrant officers are primarily formerly enlisted experts in a specific specialized field and provide leadership generally only within that speciality.

Enlisted[edit]

Enlisted marines in the pay grades E-1 to E-3 make up the bulk of the Corps’s ranks. Although they do not technically hold leadership ranks, the Corps’s ethos stresses leadership among all marines, and junior marines are often assigned responsibilities normally reserved for superiors. Those in the pay grades of E-4 and E-5 are non-commissioned officers (NCOs).[121] They primarily supervise junior Marines and act as a vital link with the higher command structure, ensuring that orders are carried out correctly. Marines E-6 and higher are staff non-commissioned officers (SNCOs), charged with supervising NCOs and acting as enlisted advisers to the command.[122]

The E-8 and E-9 levels have two and three ranks per pay grade, respectively, each with different responsibilities. The first sergeant and sergeant major ranks are command-oriented, serving as the senior enlisted marines in a unit, charged to assist the commanding officer in matters of discipline, administration, and the morale and welfare of the unit. Master sergeants and master gunnery sergeants provide technical leadership as occupational specialists in their specific MOS. The Sergeant Major of the Marine Corps also E-9, is a billet conferred on the senior enlisted marine of the entire Marine Corps, personally selected by the commandant. It is possible for an enlisted marine to hold a position senior to Sergeant Major of the Marine Corps which was the case from 2011 to 2015 with the appointment of Sergeant Major Bryan B. Battaglia to the billet of Senior Enlisted Advisor to the Chairman, who is the most senior enlisted member of the United States military, serving in the Joint Chiefs of Staff.[123]

Military Occupational Specialty[edit]

The Military Occupational Specialty (MOS) is a system of job classification. Using a four digit code, it designates what field and specific occupation a Marine performs. Segregated between officer and enlisted, the MOS determines the staffing of a unit. Some MOSs change with rank to reflect supervisory positions; others are secondary and represent a temporary assignment outside of a Marine’s normal duties or special skill.[citation needed]

Initial training[edit]

Every year, over 2,000 new Marine officers are commissioned, and 38,000 recruits are accepted and trained.[31] All new marines, enlisted or officer, are recruited by the Marine Corps Recruiting Command.[124]

Commissioned officers are commissioned mainly through one of three sources: Naval Reserve Officer Training Corps, Officer Candidates School, or the United States Naval Academy. Following commissioning, all Marine commissioned officers, regardless of accession route or further training requirements, attend The Basic School at Marine Corps Base Quantico. At The Basic School, second lieutenants, warrant officers, and selected foreign officers learn the art of infantry and combined arms warfare.[17]

Enlisted marines attend recruit training, known as boot camp, at either Marine Corps Recruit Depot San Diego or Marine Corps Recruit Depot Parris Island. Historically, the Mississippi River served as a dividing line that delineated who would be trained where, while more recently, a district system has ensured a more even distribution of male recruits between the two facilities. All recruits must pass a fitness test to start training; those who fail will receive individualized attention and training until the minimum standards are reached.[125] Marine recruit training is the longest among the American military services; it is 13 weeks long including processing and out-processing.[126]

Following recruit training, enlisted marines then attend The School of Infantry at Camp Geiger or Camp Pendleton. Infantry marines begin their combat training, which varies in length, immediately with the Infantry Training Battalion. Marines in all other MOSs train for 29 days in Marine Combat Training, learning common infantry skills, before continuing on to their MOS schools, which vary in length.[127]

Uniforms[edit]

The Marine Corps has the most stable and most recognizable uniforms in the American military; the Dress Blues dates back to the early 19th century[31] and the service uniform to the early 20th century. Only a handful of skills (parachutist, air crew, explosive ordnance disposal, etc.) warrant distinguishing badges, and rank insignia is not worn on uniform headgear (with the exception of an officer’s garrison service cover).

Marines have four main uniforms: dress, service, utility, and physical training. These uniforms have a few minor but very distinct variations from enlisted personnel to commissioned and non-commissioned officers. The Marine Corps dress uniform is the most elaborate, worn for formal or ceremonial occasions. There are four different forms of the dress uniform. The variations of the dress uniforms are known as «Alphas», «Bravos», «Charlies», or «Deltas». The most common being the «Blue Dress Alphas or Bravos», called «Dress Blues» or simply «Blues». It is most often seen in recruiting advertisements and is equivalent to black tie. There is a «Blue-White» Dress for summer, and Evening Dress for formal (white tie) occasions, which are reserved for SNCO’s and officers. Versions with a khaki shirt in lieu of the coat (Blue Dress Charlie/Delta) are worn as a daily working uniform by Marine recruiters and NROTC staff.[128]

The service uniform was once the prescribed daily work attire in garrison; however, it has been largely superseded in this role by the utility uniform. Consisting of olive green and khaki colors. It is roughly equivalent in function and composition to a business suit.[128][failed verification]

The utility uniform, currently the Marine Corps Combat Utility Uniform, is a camouflage uniform intended for wear in the field or for dirty work in garrison, though it has been standardized for regular duty. It is rendered in MARPAT pixelated camouflage that breaks up the wearer’s shape. In garrison, the woodland and desert uniforms are worn depending on the marine’s duty station.[129][better source needed] Marines consider the utilities a working uniform and do not permit their wear off-base, except in transit to and from their place of duty and in the event of an emergency.[128]

Culture[edit]

Official traditions and customs[edit]

As in any military organization, the official and unofficial traditions of the Marine Corps serve to reinforce camaraderie and set the service apart from others. The Corps’s embrace of its rich culture and history is cited as a reason for its high esprit de corps.[17] An important part of the Marine Corps culture is the traditional seafaring naval terminology derived from its history with the Navy. «Marines» are not «soldiers» or «sailors».[130]

The Marine Corps emblem is the Eagle, Globe, and Anchor, sometimes abbreviated «EGA», adopted in 1868.[131] The Marine Corps seal includes the emblem, also is found on the flag of the United States Marine Corps, and establishes scarlet and gold as the official colors.[132] The Marine motto Semper Fidelis means Always Faithful in Latin, often appearing as Semper Fi. The Marines’ Hymn dates back to the 19th century and is the oldest official song in the United States armed forces. Semper Fi is also the name of the official march of the Corps, composed by John Philip Sousa. The mottos «Fortitudine» (With Fortitude); By Sea and by Land, a translation of the Royal Marines’ Per Mare, Per Terram; and To the Shores of Tripoli were used until 1868.[133]

The «Marines’ Hymn» performed in 1944 by the Boston Pops.

Two styles of swords are worn by marines: the officers’ Mameluke Sword, similar to the Persian shamshir presented to Lt. Presley O’Bannon after the Battle of Derna, and the Marine NCO sword.[31] The Marine Corps Birthday is celebrated every year on 10 November in a cake-cutting ceremony where the first slice of cake is given to the oldest marine present, who in turn hands it off to the youngest marine present. The celebration includes a reading of Commandant Lejeune’s Birthday Message.[134] Close Order Drill is heavily emphasized early on in a marine’s initial training, incorporated into most formal events, and is used to teach discipline by instilling habits of precision and automatic response to orders, increase the confidence of junior officers and noncommissioned officers through the exercise of command and give marines an opportunity to handle individual weapons.[135]

Unofficial traditions and customs[edit]

Marines have several generic nicknames:

- Devil Dog: German soldiers during the First World War said that at Belleau Wood the marines were so vicious that the German infantrymen called them Teufel Hunden – ‘devil dogs’.[136][137][138][139]

- Gyrene: commonly used between fellow marines.[140]

- Leatherneck: refers to a leather collar formerly part of the Marine uniform during the Revolutionary War period.[141]

- Jarhead has several oft-disputed explanations.[142]

Some other unofficial traditions include mottos and exclamations:

- Oorah is common among marines, being similar in function and purpose to the Army, Air Force, and Space Force’s hooah and the Navy’s hooyah cries. Many possible etymologies have been offered for the term.[143]

- Semper Fi is a common greeting among serving and veteran marines.

- Improvise, Adapt and Overcome has become an adopted mantra in many units.[144]

The Marines have historically had issues with extremism in their ranks, particularly White supremacy. In 1976 the Camp Pendleton Chapter of the Ku Klux Klan had over 100 members and was headed by an active duty marine. In 1986, a number of marines were implicated in the theft of weapons for the White Patriot Party. The USMC, along with the rest of the military, has since made a serious effort to address extremism in the ranks.[145]

Veteran marines[edit]

The Corps encourages the idea that «marine» is an earned title, and most Marine Corps personnel take to heart the phrase, «Once a marine, Always a marine». They reject the term «ex-marine» in most circumstances. There are no regulations concerning the address of persons who have left active service, so a number of customary terms have come into common use.[67]

Martial arts program[edit]

In 2001, the Marine Corps initiated an internally designed martial arts program, called Marine Corps Martial Arts Program (MCMAP). Because of an expectation that urban and police-type peacekeeping missions would become more common in the 21st century, placing marines in even closer contact with unarmed civilians, MCMAP was implemented to provide marines with a larger and more versatile set of less-than-lethal options for controlling hostile, unarmed individuals. It is a stated aim of the program to instill and maintain the «Warrior Ethos» within marines.[146] The MCMAP is an eclectic mix of different styles of martial arts melded together. MCMAP consists of punches and kicks from Taekwondo and Karate, opponent weight transfer from Jujitsu, ground grappling involving joint locking techniques and chokes from Brazilian jiu-jitsu, and a mix of knife and baton/stick fighting derived from Eskrima, and elbow strikes and kick boxing from Muay Thai. Marines begin MCMAP training in boot camp, where they will earn the first of five available belts. The belts begin at tan and progress to black and are worn with standard utility uniforms.[147]

Equipment[edit]

As of 2013, the typical infantry rifleman carries $14,000 worth of gear (excluding night-vision goggles), compared to $2,500 a decade earlier. The number of pieces of equipment (everything from radios to trucks) in a typical infantry battalion has also increased, from 3,400 pieces of gear in 2001 to 8,500 in 2013.[148]

Infantry weapons[edit]

The infantry weapon of the Marine Corps is the M27 IAR[149] service rifle. Most non-infantry marines have been equipped with the M4 Carbine[150] or Colt 9mm SMG.[151] The standard side arm is the SIG Sauer M17/M18[152] The M18 will replace all other pistols in the Marine Corps inventory, including the M9, M9A1, M45A1 and M007, as the M45A1 Close Quarter Battle Pistol (CQBP) in small numbers. Suppressive fire is provided by the, M249 SAW, and M240 machine guns, at the squad and company levels respectively. In 2018, the M27 IAR was selected to be the standard issue rifle for all infantry squads.[153] In 2021, the Marine Corps committed to fielding suppressors to all its infantry units, making it the first branch of the U.S. military to adopt them for widespread use.[154]