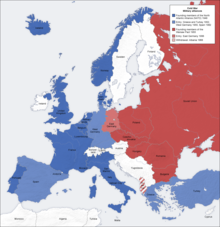

«Оттепель» — неофициальное обозначение периода в истории СССР после смерти И. В. Сталина (середина 50-х — середина 60-х годов). Характеризовался во внутриполитической жизни СССР осуждением культа личности Сталина, репрессий 1930-х гг., либерализацией режима, освобождением политических заключенных, ликвидацией ГУЛАГа, отказом власти от решения внутренних споров путем насилия, ослаблением тоталитарной власти, появлением некоторой свободы слова, относительной демократизацией политической и общественной жизни, открытостью западному миру, большей свободой творческой деятельности. Название связано с пребыванием на посту Первого секретаря ЦК КПСС Н. Хрущёва (1953—1964).

История

Начальной точкой «хрущёвской оттепели» послужила смерть Сталина в 1953 году. К «оттепели» относят также недолгий период, когда у руководства страны находился Георгий Маленков и были закрыты крупные уголовные дела («Ленинградское дело», «Дело врачей»), прошла амнистия осуждённых за незначительные преступления. В эти годы в системе ГУЛАГа вспыхивают восстания заключённых: Норильское восстание, Воркутинское восстание, Кенгирское восстание и др.

Десталинизация

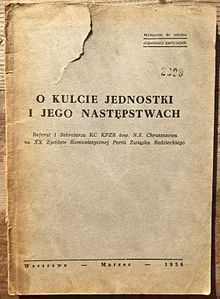

С укреплением у власти Хрущёва «оттепель» стала ассоциироваться с осуждением культа личности Сталина. Вместе с тем, в 1953—1955 годах Сталин ещё продолжал официально почитаться в СССР как великий лидер; в тот период на портретах они часто изображались вдвоём с Лениным. На XX съезде КПСС в 1956 году Н. С. Хрущёв сделал доклад «О культе личности и его последствиях», в котором были подвергнуты критике культ личности Сталина и сталинские репрессии, а во внешней политике СССР был провозглашён курс на «мирное сосуществование» с капиталистическим миром. Хрущёв также начал сближение с Югославией, отношения с которой были разорваны при Сталине. В целом, новый курс был поддержан в верхах партии и соответствовал интересам номенклатуры, так как ранее даже самым видным партийным деятелям, попавшим в опалу, приходилось бояться за свою жизнь. Многие выжившие политические заключённые в СССР и странах социалистического лагеря были выпущены на свободу и реабилитированы. С 1953 года были образованы комиссии по проверке дел и реабилитации. Было разрешено возвращение на родину большинству народов, депортированных в 1930-е—1940-е гг. Либерализовано трудовое законодательство (в 1956 году отменена уголовная ответственность за прогул). На родину были отправлены десятки тысяч немецких и японских военнопленных. В некоторых странах к власти пришли относительно либеральные руководители, такие как Имре Надь в Венгрии. Была достигнута договорённость о государственном нейтралитете Австрии и выводе из нее всех оккупационных войск. В 1955 г. Хрущёв встретился в Женеве с президентом США Дуайтом Эйзенхауэром и главами правительств Великобритании и Франции. Вместе с тем, десталинизация чрезвычайно негативно повлияла на отношения с маоистским Китаем. КПК осудила десталинизацию как ревизионизм. В 1957 году Президиум Верховного Совета СССР запретил присвоение городам и заводам имён партийных деятелей при их жизни.

Пределы и противоречия «оттепели»

Период оттепели продлился недолго. Уже с подавлением Венгерского восстания 1956 года проявились чёткие границы политики открытости. Партийное руководство было напугано тем, что либерализация режима в Венгрии привела к открытым антикоммунистическим выступлениям и насилию, соответственно, либерализация режима в СССР может привести к тем же последствиям. Президиум ЦК КПСС 19 декабря 1956 г. утвердил текст Письма ЦК КПСС «Об усилении политической работы партийных организаций в массах и пресечении вылазок антисоветских, враждебных элементов». В нём говорилось: «Центральный комитет Коммунистической партии Советского Союза считает необходимым обратиться ко всем парторганизациям… для того, чтобы привлечь внимание партии и мобилизовать коммунистов на усиление политической работы в массах, на решительную борьбу по пресечению вылазок антисоветских элементов, которые в последнее время, в связи с некоторым обострением международной обстановки, активизировали свою враждебную деятельность против Коммунистической партии и Советского государства». Далее говорилось об имеющей место за последнее время «активизации деятельности антисоветских и враждебных элементов». Прежде всего, это «контрреволюционный заговор против венгерского народа», задуманный под вывеской «фальшивых лозунгов свободы и демократии» с использованием «недовольства значительной части населения, вызванного тяжёлыми ошибками, допущенными бывшим государственным и партийным руководством Венгрии». Также указывалось: «За последнее время среди отдельных работников литературы и искусства, сползающих с партийных позиций, политически незрелых и настроенных обывательски, появились попытки подвергнуть сомнению правильность линии партии в развитии советской литературы и искусства, отойти от принципов социалистического реализма на позиции безыдейного искусства, выдвигаются требования „освободить“ литературу и искусство от партийного руководства, обеспечить „свободу творчества“, понимаемую в буржуазно-анархистском, индивидуалистическом духе». В письме содержалось указание коммунистам, работающим в органах государственной безопасности, «зорко стоять на страже интересов нашего социалистического государства, быть бдительным к проискам враждебных элементов и, в соответствии с законами Советской власти, своевременно пресекать преступные действия». Прямым следствием этого письма стало значительное увеличение в 1957 г. числа осуждённых за «контрреволюционные преступления» (2948 человек, что в 4 раза больше, чем в 1956 г.). Студенты за критические высказывания исключались из институтов.

«Оттепель» в искусстве

Во время периода десталинизации заметно ослабела цензура, прежде всего в литературе, кино и других видах искусства, где стало возможным более критическое освещение действительности. «Первым поэтическим бестселлером» оттепели стал сборник стихов Леонида Мартынова (Стихи. М., Молодая гвардия, 1955). Главной платформой сторонников «оттепели» стал литературный журнал «Новый мир». Некоторые произведения этого периода получили известность и за рубежом, в том числе роман Владимира Дудинцева «Не хлебом единым» и повесть Александра Солженицына «Один день Ивана Денисовича». Другими значимыми представителями периода оттепели были писатели и поэты Виктор Астафьев, Владимир Тендряков, Белла Ахмадулина, Роберт Рождественский, Андрей Вознесенский, Евгений Евтушенко. Было резко увеличено производство фильмов. Григорий Чухрай первым в киноискусстве затронул тему десталинизации и оттепели в фильме «Чистое небо» (1963). Основные кинорежиссёры оттепели — Марлен Хуциев, Михаил Ромм, Георгий Данелия, Эльдар Рязанов, Леонид Гайдай. Важным культурным событием стали фильмы — «Карнавальная ночь», «Застава Ильича», «Весна на Заречной улице», «Идиот», «Я шагаю по Москве», «Человек-амфибия», «Добро пожаловать, или Посторонним вход воспрещён» и другие. В 1955—1964 годах на территорию большей части страны была распространена телетрансляция. Телестудии открыты во всех столицах союзных республик и во многих областных центрах. В Москве в 1957 году проходит VI Всемирный фестиваль молодёжи и студентов.

Усиление давления на религиозные объединения

В 1956 г. началась активизация антирелигиозной борьбы. Секретное постановление ЦК КПСС «О записке отдела пропаганды и агитации ЦК КПСС по союзным республикам „О недостатках научно-атеистической пропаганды“» от 4 октября 1958 года обязывало партийные, комсомольские и общественные организации развернуть пропагандистское наступление на «религиозные пережитки»; государственным учреждениям предписывалось осуществить мероприятия административного характера, направленные на ужесточение условий существования религиозных общин. 16 октября 1958 года Совет Министров СССР принял Постановления «О монастырях в СССР» и «О повышении налогов на доходы епархиальных предприятий и монастырей». 21 апреля 1960 года назначенный в феврале того же года новый председатель Совета по делам РПЦ Куроедов в своём докладе на Всесоюзном совещании уполномоченных Совета так характеризовал работу прежнего его руководства: «Главная ошибка Совета по делам православной церкви заключалась в том, что он непоследовательно проводил линию партии и государства в отношении церкви и скатывался зачастую на позиции обслуживания церковных организаций. Занимая защитнические позиции по отношению к церкви, совет вёл линию не на борьбу с нарушениями духовенством законодательства о культах, а на ограждение церковных интересов.» Секретная инструкция по применению законодательства о культах в марте 1961 года обращала особое внимание на то, что служители культа не имеют права вмешиваться в распорядительную и финансово-хозяйственную деятельность религиозных общин. В инструкции впервые были определены не подлежавшие регистрации «секты, вероучение и характер деятельности которых носит антигосударственный и изуверский характер: иеговисты, пятидесятники, адвентисты-реформисты». В массовом сознании сохранилось приписываемое Хрущёву высказывание того периода, в котором он обещает показать последнего попа по телевизору в 1980 году.

Конец «оттепели»

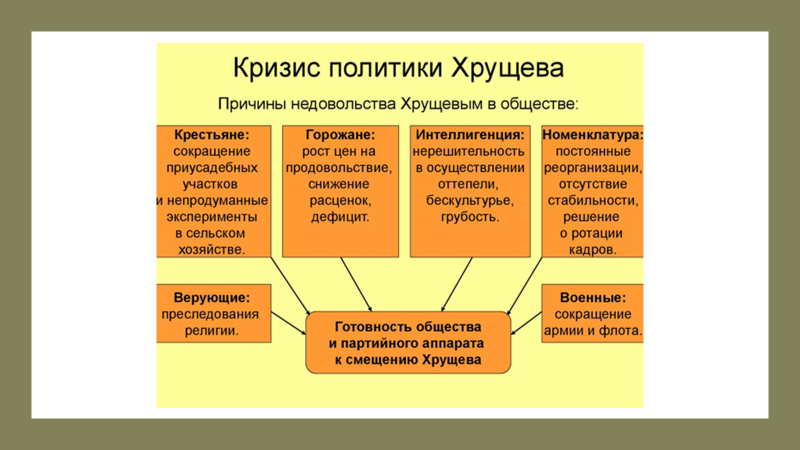

Завершением «оттепели» считается отстранение Хрущёва и приход к руководству Леонида Брежнева в 1964 году. Впрочем, ужесточение внутриполитического режима и идеологического контроля было начато ещё во время правления Хрущёва после окончания Карибского кризиса. Десталинизация была остановлена, а в связи с празднованием 20-й годовщины победы в Великой Отечественной войне начался процесс возвеличивания роли победы советского народа в войне. Личность Сталина старались как можно больше обходить стороной, он так и не был реабилитирован. В БСЭ о нём осталась нейтральная статья. В 1979 году по случаю 100-летия Сталина вышло несколько статей, но особых торжеств не устраивали. Массовые политические репрессии, однако, не были возобновлены, а лишённый власти Хрущёв ушёл на пенсию и даже оставался членом партии. Незадолго перед этим сам Хрущев раскритиковал понятие «оттепель» и даже назвал придумавшего его Эренбурга «жуликом». Ряд исследователей полагает, что окончательно оттепель закончилась в 1968 году после подавления «Пражской весны» С завершением «оттепели» критика советской действительности стала распространяться лишь по неофициальным каналам, таким как Самиздат.

Период оттепели

4.5

Средняя оценка: 4.5

Всего получено оценок: 765.

4.5

Средняя оценка: 4.5

Всего получено оценок: 765.

Период Оттепели в СССР относится к рубежу 1950-1960-ых годов, когда руководителем государства был Никита Сергеевич Хрущев. Он занимал должность первого секретаря КПСС с 1953 по 1964 год. Эпоха Хрущева в истории СССР была отмечена рядом реформ, весьма спорных по своим результатам.

Начало процесса

Первыми событиями, которые можно отнести к Оттепели Хрущева можно считать амнистию 1953 года и прекращения ряда дел сталинского периода, например, Ленинградского или “Дела врачей”.

В большей степени советские граждане почувствовали оттепель с 1956 года, когда началась критика “культа личности” Сталина. Это совпало с внешнеполитическими событиями, например, с нормализацией отношений Австрией и с Югославией и ее лидером Тито, так как при Сталине его считали едва ли врагом, как и страны НАТО. С 1953 года началась проверка дел и реабилитации бывших заключенных, а также расстрелянных, особенно, в 1930-ые годы, среди них были и бывшие маршалы – Тухачевский, Блюхер, Егоров. В 1957 году началось возвращение в места своего проживания депортированных народов:

- Балкарцев и карачаевцев.

- Чеченцев и ингушей.

- Калмыков.

Были восстановлены их республики, но на другие народы эти меры не распространились. Это относится к корейцам, болгарам, понтийским грекам, курдам, крымским татарам, немцам Поволжья.

Однако, такие меры не мешали власти в 1956 году подавлять просталинские выступления в Тбилиси или преследовать Бориса Пастернака за публикацию романа “Доктор Живаго” в Италии.

К 1957 году СССР покинули все иностранные военнопленные. В том же году запрещено присвоение населенных пунктам и объектам народного хозяйства имен живых государственных деятелей. Также был снят запрет 1936 года на аборты и проведен VI Всемирный фестиваль молодежи и студентов.

События оттепели 1959-1964 годов

В 1958 году из советского Уголовного Кодекса удалено понятие “враг народа”, однако, в государстве сохранилась и продолжала применять смертная казнь. В 1962 году была расстреляна демонстрация в Новочеркасске, а в 1964 арестован Иосиф Бродский.

Одновременно с этим началась новая волна гонений на православную церковь, впервые с конца 1930-ых годов. Десталинизация достигла своего пика в 1961 году, когда XXII съезд КПСС в очередной раз осудил культ личности. По всей стране провел массовый демонтаж памятников бывшему руководителю СССР, были переименованы многие города и другие объекты. Полемика по поводу культа личности привела к разрыву в декабре 1961 года дипломатических отношений с Албанией до 1990 года. Тело Сталина вынесли из мавзолея и похоронили около Кремлевской стены.

В 1955-1964 годах заметно ослабла цензура, поэтому начали публиковаться произведения Солженицына. В те годы продуктивно работали следующие кинорежиссеры: Чухрай, Хуциев, Гайдай, Данелия.

Концом “Оттепели” принято считать осень 1964 года, когда Хрущева сняли со всех руководящих постов. Некоторые ее процессы по инерции продолжались до 1968 года, то есть до подавления выступлений в Чехословакии.

Что мы узнали?

Кратко о главном о хрущевской оттепели рассказывает школьный курс истории 9 класса. Даже беглого знакомства с ее событиями достаточно для понимания того, что это был неоднозначный процесс. В ряде сфер государство допустило либерализацию, о и репрессивные меры применялись.

Тест по теме

Доска почёта

Чтобы попасть сюда — пройдите тест.

Пока никого нет. Будьте первым!

Оценка доклада

4.5

Средняя оценка: 4.5

Всего получено оценок: 765.

А какая ваша оценка?

The Khrushchev Thaw (Russian: хрущёвская о́ттепель, tr. khrushchovskaya ottepel, IPA: [xrʊˈɕːɵfskəjə ˈotʲ:ɪpʲɪlʲ] or simply ottepel)[1] is the period from the mid-1950s to the mid-1960s when repression and censorship in the Soviet Union were relaxed due to Nikita Khrushchev’s policies of de-Stalinization[2] and peaceful coexistence with other nations. The term was coined after Ilya Ehrenburg’s 1954 novel The Thaw («Оттепель»),[3] sensational for its time.

The Thaw became possible after the death of Joseph Stalin in 1953. First Secretary Khrushchev denounced former General Secretary Stalin[4] in the «Secret Speech» at the 20th Congress of the Communist Party,[5][6] then ousted the Stalinists during his power struggle in the Kremlin. The Thaw was highlighted by Khrushchev’s 1954 visit to Beijing, China, his 1955 visit to Belgrade, Yugoslavia (with whom relations had soured since the Tito–Stalin Split in 1948), and his subsequent meeting with Dwight Eisenhower later that year, culminating in Khrushchev’s 1959 visit to the United States.

The Thaw allowed some freedom of information in the media, arts, and culture; international festivals; foreign films; uncensored books; and new forms of entertainment on the emerging national TV, ranging from massive parades and celebrations to popular music and variety shows, satire and comedies, and all-star shows[7] like Goluboy Ogonyok. Such political and cultural updates altogether had a significant influence on the public consciousness of several generations of people in the Soviet Union.[8][9]

Leonid Brezhnev, who succeeded Khrushchev, put an end to the Thaw. The 1965 economic reform of Alexei Kosygin was de facto discontinued by the end of the 1960s, while the trial of the writers Yuli Daniel and Andrei Sinyavsky in 1966—the first such public trial since Stalin’s reign—and the invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968 identified reversal of the liberalization of the country.

Khrushchev and Stalin[edit]

Khrushchev’s Thaw had its genesis in the concealed power struggle among Stalin’s lieutenants.[1] Several major leaders among the Red Army commanders, such as Marshal Georgy Zhukov and his loyal officers, had some serious tensions with Stalin’s secret service.[1][10] On the surface, the Red Army and the Soviet leadership seemed united after their victory in World War II. However, the hidden ambitions of the top people around Stalin, as well as Stalin’s own suspicions, had prompted Khrushchev that he could rely only on those few; they would stay with him through the entire political power struggle.[10][11] That power struggle was surreptitiously prepared by Khrushchev while Stalin was alive,[1][10] and came to surface after Stalin’s death in March 1953.[10] By that time, Khrushchev’s people were planted everywhere in the Soviet hierarchy, which allowed Khrushchev to execute, or remove his main opponents, and then introduce some changes in the rigid Soviet ideology and hierarchy.[1]

Stalin’s leadership had reached new extremes in ruling people at all levels,[12] such as the deportations of nationalities, the Leningrad Affair, the Doctors’ plot, and official criticisms of writers and other intellectuals. At the same time, millions of soldiers and officers had seen Europe after World War II, and had become aware of different ways of life which existed outside the Soviet Union. Upon Stalin’s orders many were arrested and punished again,[12] including the attacks on the popular Marshal Georgy Zhukov and other top generals, who had exceeded the limits on taking trophies when they looted the defeated nation of Germany. The loot was confiscated by Stalin’s security apparatus, and Marshal Zhukov was demoted, humiliated and exiled; he became a staunch anti-Stalinist.[13] Zhukov waited until the death of Stalin, which allowed Khrushchev to bring Zhukov back for a new political battle.[1][14]

The temporary union between Nikita Khrushchev and Marshal Georgy Zhukov was founded on their similar backgrounds, interests and weaknesses:[1] both were peasants, both were ambitious, both were abused by Stalin, both feared the Stalinists, and both wanted to change these things. Khrushchev and Zhukov needed one another to eliminate their mutual enemies in the Soviet political elite.[14][15]

In 1953, Zhukov helped Khrushchev to eliminate Lavrenty Beria,[1] then a First Vice-Premier, who was promptly executed in Moscow, as well as several other figures of Stalin’s circle. Soon Khrushchev ordered the release of millions of political prisoners from the Gulag camps. Under Khrushchev’s rule the number of prisoners in the Soviet Union was decreased, according to some writers, from 13 million to 5 million people.[12]

Khrushchev also promoted and groomed Leonid Brezhnev,[14] whom he brought to the Kremlin and introduced to Stalin in 1952.[1] Then Khrushchev promoted Brezhnev to Presidium (Politburo) and made him the Head of Political Directorate of the Red Army and Navy, and moved him up to several other powerful positions. Brezhnev in return helped Khrushchev by tipping the balance of power during several critical confrontations with the conservative hard-liners, including the ouster of pro-Stalinists headed by Molotov and Malenkov.[14][16]

Khrushchev’s 1956 speech denouncing Stalin[edit]

Khrushchev denounced Stalin in his speech On the Cult of Personality and Its Consequences, delivered at the closed session of the 20th Party Congress, behind closed doors, after midnight on 25 February 1956.[17] After the delivery of the speech, it was officially disseminated in a shorter form among members of the Soviet Communist Party across the USSR starting 5 March 1956.[1]

Together with his ally Anastas Mikoyan and a small but prominent group of Gulag returnees, Khrushchev also initiated a wave of rehabilitations.[18] This action officially restored the reputations of many millions of innocent victims, who were killed or imprisoned in the Great Purge under Stalin.[17] Further, tentative moves were made through official and unofficial channels to relax restrictions on freedom of speech that had been held over from the rule of Stalin.[1]

Khrushchev’s 1956 speech was the strongest effort ever in the USSR to bring political change,[1] at that time, after several decades of fear of Stalin’s rule, that took countless innocent lives.[19] Khrushchev’s speech was published internationally within a few months,[1] and his initiatives to open and liberalize the USSR had surprised the world. Khrushchev’s speech had angered many of his powerful enemies, thus igniting another round of ruthless power struggle within the Soviet Communist Party.

Issues and tensions[edit]

Georgian revolt[edit]

Khrushchev’s denouncement of Stalin came as a shock to the Soviet people. Many in Georgia, Stalin’s homeland, especially the young generation, bred on the panegyrics and permanent praise of the «genius» of Stalin, perceived it as a national insult. In March 1956, a series of spontaneous rallies to mark the third anniversary of Stalin’s death quickly evolved into an uncontrollable mass demonstration and political demands such as the change of the central government in Moscow and calls for the independence of Georgia from the Soviet Union appeared,[20] leading to the Soviet army intervention and bloodshed in the streets of Tbilisi.[21]

Polish and Hungarian Revolutions of 1956[edit]

The first big international failure of Khrushchev’s politics came in October–November 1956.

The Hungarian Revolution of 1956 was suppressed by a massive invasion of Soviet tanks and Red Army troops in Budapest. The street fighting against the invading Red Army caused thousands of casualties among Hungarian civilians and militia, as well as hundreds of the Soviet military personnel killed. The attack by the Soviet Red Army also caused massive emigration from Hungary, as hundreds of thousands of Hungarians had fled as refugees.[22]

At the same time, the Polish October emerged as the political and social climax in Poland. Such democratic changes in the internal life of Poland were also perceived with fear and anger in Moscow, where the rulers did not want to lose control, fearing the political threat to Soviet security and power in Eastern Europe.[23]

1957 plot against Khrushchev[edit]

A faction of the Soviet communist party was enraged by Khrushchev’s speech in 1956, and rejected Khrushchev’s de-Stalinization and liberalization of Soviet society. One year after Khrushchev’s secret speech, the Stalinists attempted to oust Khrushchev from the leadership position in the Soviet Communist Party.[1]

Khrushchev’s enemies considered him hypocritical as well as ideologically wrong, given Khrushchev’s involvement in Stalin’s Great Purges, and other similar events as one of Stalin’s favorites. They believed that Khrushchev’s policy of peaceful coexistence would leave the Soviet Union open to attack. Vyacheslav Molotov, Lazar Kaganovich, Georgy Malenkov, and Dmitri Shepilov,[17] who joined at the last minute after Kaganovich convinced him the group had a majority, attempted to depose Khrushchev as First Secretary of the Party in May 1957.[1]

However, Khrushchev had used Marshal Georgy Zhukov again. Khrushchev was saved by several strong appearances in his support – especially powerful was support from both Zhukov and Mikoyan.[24] At the extraordinary session of the Central Committee held in late June 1957, Khrushchev labeled his opponents the Anti-Party Group[17] and won a vote which reaffirmed his position as First Secretary.[1] He then expelled Molotov, Kaganovich, and Malenkov from the Secretariat and ultimately from the Communist Party itself.

Economy and political tensions[edit]

Khrushchev’s attempts in reforming the Soviet industrial infrastructure led to his clashes with professionals in most branches of the Soviet economy. His reform of administrative organization caused him more problems. In a politically motivated move to weaken the central state bureaucracy in 1957, Khrushchev replaced the industrial ministries in Moscow with regional Councils of People’s Economy, sovnarkhozes, making himself many new enemies among the ranks in Soviet government.[24]

Khrushchev’s power, although indisputable, had never been comparable to that of Stalin’s, and eventually began to fade. Many of the new officials who came into the Soviet hierarchy, such as Mikhail Gorbachev, were younger, better educated, and more independent thinkers.[25]

In 1956, Khrushchev introduced the concept of a minimum wage. The idea was met with much criticism from communist hardliners, who claimed that the minimum wage was too low and that most people were still underpaid in reality. The next step was a contemplated financial reform. However, Khrushchev stopped short of real monetary reform, and made a simple redenomination of the rouble at 10:1 in 1961.

In 1961, Khrushchev finalized his battle against Stalin: the body of the dictator was removed from Lenin’s Mausoleum on the Red Square and then buried outside the walls of the Kremlin.[1][10][14][24][26] The removal of Stalin’s body out of Lenin’s Mausoleum was arguably among the most provocative moves made by Khrushchev during the Thaw. The removal of Stalin’s body consolidated pro-Stalinists against Khrushchev,[1][14] and alienated even his loyal apprentices, such as Leonid Brezhnev.[citation needed]

Openness and cultural liberalization[edit]

After the early 1950s, Soviet society enjoyed a series of cultural and sports events and entertainment of unprecedented scale, such as the first Spartakiad, as well as several innovative film comedies, such as Carnival Night, and several popular music festivals. Some classical musicians, filmmakers and ballet stars were allowed to make appearances outside the Soviet Union in order to better represent its culture and society to the world.[17]

The first Soviet academics to visit the United States in an official capacity following World War II were biochemist Andrey Kursanov and historian Boris Rybakov, who attended the Columbia University Bicentennial in New York City as representatives of the Academy of Sciences of the Soviet Union.[27] Earlier attempts by American institutions, such as Princeton in 1946, to invite Soviet scholars to the United States had been frustrated.[28] The decision to allow Kursanov and Rybakov to attend marked the beginning of a new period of academic exchange between the Soviet Union and the United States: Columbia University repaid the visit in 1955, when it sent its own representatives to the bicentennial of Moscow State University,[29] and by 1958 the universities had established an exchange program for students and faculty.[30]

In 1956, an agreement was achieved between the Soviet and US Governments to resume the publication and distribution in the Soviet Union of the US-produced magazine Amerika, and to launch its counterpart, the USSR magazine in the US.[31]

In the summer of 1956, just a few months after Khrushchev’s secret speech, Moscow became the center of the first Spartakiad of the Peoples of the USSR. The event was made pompous in the Soviet style: Moscow hosted large sports teams and groups of fans in national costumes who came from all Union republics. Khrushchev used the event to accentuate his new political and social goals, and to show himself as a new leader who was completely different from Stalin.[1][14]

In July 1957, the 6th World Festival of Youth and Students was held in Moscow. It was the first World Festival of Youth and Students held in the Soviet Union, which was opening its doors for the first time to the world. The festival attracted 34,000 people from 130 countries.[32]

In 1958, the first International Tchaikovsky Competition was held in Moscow. The winner was American pianist Van Cliburn, who gave sensational performances of Russian music. Khrushchev personally approved giving the top award to the American musician.[1]

Khrushchev’s Thaw opened the Soviet society to a degree that allowed some foreign movies, books, art and music. Some previously banned writers and composers, such as Anna Akhmatova and Mikhail Zoshchenko, among others, were brought back to public life, as the official Soviet censorship policies had changed. Books by some internationally recognized authors, such as Ernest Hemingway, were published in millions of copies to satisfy the interest of readers in the USSR.

In 1962, Khrushchev personally approved the publication of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s story One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, which became a sensation, and made history as the first uncensored publication about Gulag labor camps.[1]

Actions against religion that had temporarily halted during the war effort and the years after toward the end of Stalin’s rule, intensified under Khrushchev, a new campaign launched in 1959. Khrushchev closed around 11000 of the 20000 working church buildings that were around in 1959 and introduced many restrictions on all kinds of denominations.[33]He closed, of the 1500 working mosques in 1959, around 1100.[34]

The era of the Cultural Thaw ended in December 1962 after the Manege Affair.

Music[edit]

Censorship of the arts relaxed throughout the Soviet Union. During this time of liberalization, Russian composers, performers, and listeners of music experienced a newfound openness in musical expression which led to the foundation of an unofficial music scene from the mid 1950s to the 1970s.[35]

Despite these liberalizing reforms in music, some have argued that Khrushchev’s legislation of the arts was based more his own personal tastes than the principle of freedom of expression. Following the emergence of some unconventional, avant-garde music as a result of his reforms, on 8 March 1963, Khrushchev delivered a speech which began to reverse some of his de-Stalinization reforms, in which he stated: «We flatly reject this cacophonous music. Our people can’t use this garbage as a tool for their ideology.» and «Society has a right to condemn works which are contrary to the interests of the people.»[36] Although the Thaw was considered a time of openness and liberalization, Khrushchev continued to place restrictions on these newfound freedoms.

Nonetheless, despite Khrushchev’s inconsistent liberalization of musical expression, his speeches were not so much «restrictions» as «exhortations».[36] Artists, and especially musicians, were provided access to resources that had previously been censored or altogether inaccessible prior to Khrushchev’s reforms. The composers of this time, for example, were able to access scores by composers such as Arnold Schoenberg and Pierre Boulez, gaining inspiration from and imitating previously concealed musical scores.[37]

As Soviet composers gained access to new scores and were given a taste of freedom of expression during the late 1950s, two separate groups began to emerge. One group wrote predominantly «official» music which was «sanctioned, nourished, and supported by the Composers’ Union». The second group wrote «unofficial», «left», «avant-garde», or «underground» music, marked by a general state of opposition against the Soviet Union. Although both groups are widely considered to be interdependent, many regard the unofficial music scene as more independent and politically influential than the former in the context of the Thaw.[38]

The unofficial music that emerged during the Thaw was marked by the attempt, whether successful or unsuccessful, to reinterpret and reinvigorate the «battle of form and content» of the classical music of the period.[35] Although the term «unofficial» implies a level of illegality involved in the production of this music, composers, performers, and listeners of «unofficial» music actually used «official» means of production. Rather, the music was considered unofficial within a context that counteracted, contradicted, and redefined the socialist realist requirements from within their official means and spaces.[35]

Unofficial music emerged in two distinct phases. The first phase of unofficial music was marked by performances of «escapist» pieces. From a composer’s perspective, these works were escapist in the sense that their sound and structure withdrew from the demands of socialist realism. Additionally, pieces developed during this phase of unofficial music allowed the listeners the ability to escape the familiar sounds that Soviet officials officially sanctioned.[35] The second phase of unofficial music emerged during the late 1960s, when the plots of the music became more apparent, and composers wrote in a more mimetic style, writing in contrast to their earlier compositions of the first phase.[35]

Throughout the musical Thaw, the generation of «young composers» who had matured their musical tastes with broader access to music that had previously been censored was the prime focus of the unofficial music scene. The Thaw allowed these composers the freedom to access old and new scores, especially those originating in the Western avant-garde.[35] During the late 1950s and early 1960s, young composers such as Andrei Volkonsky and Edison Denisov, among others, developed abstract musical practices that created sounds that were new to the common listener’s ear. Socialist realist music was widely considered «boring», and the unofficial concerts that the young composers presented allowed the listeners «a means of circumventing, reinterpreting, and undercutting the dominant socialist realist aesthetic codes».[37]

Despite the seemingly rebellious nature of the unofficial music of the Thaw, historians debate whether the unofficial music that emerged during this time should truly be considered as resistance to the Soviet system. While a number of participants in unofficial concerts «claimed them to be a liberating activity, connoting resistance, opposition, or protest of some sort»,[35] some critics claim that rather than taking an active role in opposing Soviet power, composers of unofficial music simply «withdrew» from the demands of the socialist realist music and chose to ignore the norms of the system.[35] Although Westerners tend to categorize unofficial composers as «dissidents» against the Soviet system, many of these composers were afraid to take action against the system in fear that it might have a negative impact on their professional advancement.[35] Many composers favored a less direct, yet significant method of opposing the system through their lack of musical compliance.

Regardless of the intentions of the composers, the effect of their music on audiences throughout the Soviet Union and abroad «helped audiences imagine alternative possibilities to those suggested by Soviet authorities, principally through the ubiquitous stylistic tropes of socialist realism».[35] Although the music of the younger generation of unofficial Soviet composers experienced little widespread success in the West, its success within the Soviet Union was apparent throughout the Thaw (Schwarz 423). Even after Khrushchev’s fall from power in October 1964, the freedoms that composers, performers, and listeners felt through unofficial concerts lasted into the 1970s.[35]

However, despite the powerful role that unofficial music played in the Soviet Union during the Thaw, much of the music that was composed during that time continued to be controlled. As a result of this, a great deal of this unofficial music remains undocumented. Consequently, much of what we know now about unofficial music in the Thaw can be sourced only through interviews with those composers, performers, and listeners who witnessed the unofficial music scene during the Thaw.[35]

International relations[edit]

The death of Stalin in 1953 and the twentieth CPSU congress of February 1956 had a huge impact throughout Eastern Europe. Literary thaws actually preceded the congress in Hungary, Poland, Bulgaria, and the GDR and later burgeoned briefly in Czechoslovakia and Chairman Mao’s China. With the exception of the arch Stalinist and anti-Titoist Albania, Romania was the only country where intellectuals avoided an open clash with the regime, influenced partly by the lack of any earlier revolt in post-war Romania that would have forced the regime to make concessions.[39]

In the West, Khrushchev’s Thaw is known as a temporary thaw in the icy tension between the United States and the USSR during the Cold War. The tensions were able to thaw because of Khrushchev’s de-Stalinization of the USSR and peaceful coexistence theory and also because of US President Eisenhower’s cautious attitude and peace attempts. For example, both leaders attempted to achieve peace by attending the 1955 Geneva International Peace Summit and developing the Open Skies Policy and Quest for Arms Agreement. The leaders’ attitudes allowed them to, as Khrushchev put it, «break the ice.»

Khrushchev’s Thaw developed largely as a result of Khrushchev’s theory of peaceful co-existence which believed the two superpowers (USA and USSR) and their ideologies could co-exist together, without war. Khrushchev had created the theory of peaceful existence in an attempt to reduce hostility between the two superpowers. He tried to prove peaceful coexistence by attending international peace conferences, such as the Geneva Summit, and by traveling internationally, such as his trip to USA’s Camp David in 1959.

This spirit of co-operation was severely damaged by the 1960 U-2 incident. The Soviet presentation of downed pilot Francis Gary Powers at the May 1960 Paris Peace Summit and Eisenhower’s refusal to apologize ended much of the progress of this era. Then Khrushchev approved the construction of the Berlin Wall in 1961.

Further deterioration of the Thaw and decay of Khrushchev’s international political standing happened during the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962. At that time, the Soviet and international media were making two completely opposite pictures of reality, while the world was at the brink of a nuclear war. Although direct communication between Khrushchev and the US president John F. Kennedy[40] helped to end the crisis, Khrushchev’s political image in the West was damaged.

Social, cultural and economic reforms[edit]

Khrushchev’s Thaw caused unprecedented social, cultural and economic transformations in the Soviet Union. The 60s generation actually started in the 1950s, with their uncensored poetry, songs and books publications.

The 6th World Festival of Youth and Students had opened many eyes and ears in the Soviet Union. Many new social trends stemmed from that festival. Many Russian women became involved in love affairs with men visiting from all over the world, what resulted in the so-called «inter-baby boom» in Moscow and Leningrad. The festival also brought new styles and fashions that caused further spread of youth subculture called «stilyagi». The festival also «revolutionized» the underground currency trade and boosted the black market.

Emergence of such popular stars as Bulat Okudzhava, Edita Piekha, Yevgeny Yevtushenko, Bella Akhmadulina, and the superstar Vladimir Vysotsky had changed the popular culture forever in the USSR. Their poetry and songs broadened the public consciousness of the Soviet people and pushed guitars and tape recorders to masses, so the Soviet people became exposed to independent channels of information and public mentality was eventually updated in many ways.

Khrushchev finally liberated millions of peasants; by his order the Soviet government gave them identifications, passports, and thus allowed them to move out of poor villages to big cities. Massive housing construction, known as khrushchevkas, were undertaken during the 1950s and 1960s. Millions of cheap and basic residential blocks of low-end flats were built all over the Soviet Union to accommodate the largest migration ever in the Soviet history, when masses of landless peasants moved to Soviet cities. The move caused a dramatic change of the demographic picture in the USSR, and eventually finalized the decay of peasantry in Russia.

Economic reforms were contemplated by Alexei Kosygin, who was chairman of the USSR State Planning Committee in 1959 and then a full member of the Presidium (also known as Politburo after 1966) in 1960.[17]

Consumerism[edit]

In 1959, the American National Exhibition came to Moscow with the goals of displaying United States’ productivity and prosperity. The latent goal of the Americans was to get the Soviet Union to reduce production of heavy industry. If the Soviet Union started putting their resources towards producing consumer goods, it would also mean a reduction of war materials. An estimated number of over twenty million Soviet citizens viewed the twenty-three U.S. exhibitions during a thirty-year period.[41] These exhibitions were part of the Cultural Agreement formed by the United States and the Soviet Union in order to acknowledge the long-term exchange of science, technology, agriculture, medicine, public health, radio, television, motion pictures, publications, government, youth, athletics, scholarly research, culture, and tourism.[42] In addition to the influences of European and Western culture, the spoils of the Cold War exposed the Soviet people to a new way of life.[43] Through motion pictures from the United States, viewers learned of another way of life.[41]

The Kitchen Debate[edit]

The Kitchen Debate at the 1959 Exhibition in Moscow fueled Khrushchev to catch up to Western consumerism. The «Khrushchev regime had promised abundance to secure its legitimacy.»[44] The ideology of strict functionality concerning material goods evolved into a more relaxed view of consumerism. American sociologist David Riesman coined the term «Operation Abundance» also known as the «Nylon War» which predicted «Russian people would not long tolerate masters who gave them tanks and spies instead of vacuum cleaners and beauty parlors.»[45] The Soviets would have to produce more consumer goods to quell mass discontent. Riesman’s theory came true to some extent as the Soviet culture changed to include consumer goods such as vacuum cleaners, washing machines, and sewing machines. These items were specifically targeted at women in the Soviet Union with the idea that they relieved women of their domestic burden. Additionally an interest in changing the western image of a dowdy Russian woman led to the cultural acceptance of beauty products. The modern Russian woman wanted the clothing, cosmetics, and hairstyles available to Western women. Under the Thaw, beauty shops selling cosmetics and perfume, which had previously only been available to the wealthy, became available for common women.[46]

Khrushchev’s Response[edit]

Khrushchev responded to consumerism more diplomatically than to cultural consumption. In response to American jazz Khrushchev stated: «I don’t like jazz. When I hear jazz, it’s as if I had gas on the stomach. I used to think it was static when I heard it on the radio.»[47] Concerning commissioning artists during the Thaw, Khrushchev declared: «As long as I am president of the Council of Ministers, we are going to support a genuine art. We aren’t going to give a kopeck for pictures painted by jackasses.»[47] In comparison, the consumption of material goods acted as a measure of economic success. Khrushchev stated: «We are producing an ever-growing quantity of all kinds of consumer goods; all the same, we must not force the pace unreasonably as regards the lowering of prices. We don’t want to lower prices to such an extent that there will be queues and a black market.»[48] Previously, excessive consumerism under Communism was seen as detrimental to the common good. Now, it was not enough for the consumer goods to be made more available; quality of consumer goods needed to be raised as well.[49] A misconception surrounding the quality of consumer goods existed because of advertising’s role in the market. Advertising controlled sale quotas by increasing the desirability of surplus sub-standard goods.[50]

Origins and outcome[edit]

The roots of consumerism started as early as the 1930s when in 1935 each Soviet Republic capital city established a model department store.[51] The department stores acted as representatives of Soviet economic success. Under Khrushchev the retail sectors gained prevalence as Soviet department stores GUM (department store) and TsUM (Central Department Store), both located in Moscow, began to focus on trade and social interaction.[52]

An increase of private housing[edit]

On 31 July 1957 the Communist party decreed to increase housing construction and Khrushchev launched plans for building private apartments that differed from the old, communal apartments that had come before. Khrushchev stated that it was important «not only to provide people with good homes, but also to teach them…to live correctly.» He saw a high living standard as a precondition leading the path on the transition to full communism and believed that private apartments could achieve this.[53] Although the Thaw marked a time of openness and liberalization primarily located in the public sphere, the emergence of private housing allowed for a new formulation of a private sphere in Soviet life.[54] This resulted in a changing ideology that needed to make room for women, who were traditionally associated with the home, and consumption of goods in order to create a well-ordered «Soviet» home.

A shift away from collective housing[edit]

Khrushchev’s policies showed an interest in rebuilding the home and the family after the devastation of World War II. Soviet rhetoric exemplified a shift in emphasis from heavy industry to the importance of consumer goods and housing.[55] The Seven-Year Plan was launched in 1958 and promised to build 12 million city apartments and 7 million rural houses.[56] Alongside the increased number of private apartments was the emergence of changing attitudes toward the family. The prior Soviet ideology disdained conceptions of the traditional family, especially under Stalin, who created the vision of a large, collective family under his paternal leadership. The new emphasis on private housing created hope that the Thaw-era private realm would provide an escape from the intensities of public life and the eye of the government.[57] Indeed, Khrushchev introduced the ideology that private life was valued and was ultimately a goal of social development.[58] The new political rhetoric regarding the family reintroduced the concept of the nuclear family, and, in doing so, cemented the idea that the women were responsible for the domestic realm and running the home.

Recognizing the necessity of rebuilding the family in the postwar years, Khrushchev enacted policies that attempted to reestablish a more conventional domestic realm, moving away from the policies of his predecessors, and most of these were aimed at women.[59] Despite being an active part of the workforce, women’s conditions were considered by the western, capitalist world to exemplify the «backwardness» of the Soviet Union. This concept goes back to traditional Marxism, which found the roots of woman’s inherent backwardness in fact that she was confined to the home; Lenin spoke of woman as a «domestic slave» who would remain in confinement as long as housework remained an activity for individuals inside the home. The prior abolition of private homes and the individual kitchen attempted to move away from the domestic regime that imprisoned women. Instead, the government tried to implement public dining, socialized housework, and collective childcare. These programs that fulfilled the original tenets of Marxism were widely resisted by traditionally-minded women.[60]

The individual kitchen[edit]

In March 1958, Khrushchev admitted to the Supreme Soviet his embarrassment about the public perception of Soviet women as unhappily relegated to the ranks of a manual laborer.[61] The new private housing provided individual kitchens for many families for the first time. The new technologies of the kitchen came to be associated with the projects of modernization in the era of the Cold War’s «peaceful competition.» In this time, the primary competition between the U.S. and the Soviet Union was the battle of providing the better quality of life.[62] In 1959, at the American National Exhibition in Moscow, U.S. Vice-President Richard Nixon declared the superiority of the capitalist system while standing in front of an example of a modern American kitchen. Known as the «Kitchen Debate,» the exchange between Nixon and Khrushchev foreshadowed Khrushchev’s increased attention to the needs of women, especially by creating modern kitchens. While affirming his dedication to increasing the living standard, Khrushchev associated the transition to communism with abundance and prosperity.[63]

The Third Party Programme of 1961, the defining document of Khrushchev’s policies, related social progress with technological progress, especially technological progress inside the home. Khrushchev spoke of a commitment to increasing production of consumer goods, specifically household goods and appliances that would decrease the intensity of housework. The kitchen was defined as a «workshop» that relied on the «correct organization of labour» to be most efficient. Creating what were perceived to be the best conditions for the woman’s work in the kitchen was an attempt on the part of the government to ensure that the Soviet woman would be able to continue her labor inside and outside of the home. Despite the increasing demands of housework, women were expected to maintain jobs outside the home in order to sustain the national economy as well as fulfill the ideals of a Soviet well-rounded individual.[64]

During this time, women were flooded with pamphlets and magazines teeming with advice on how best to run a household. This literature emphasized the virtues of simplicity and efficiency.[65] Additionally, furniture was designed to suit the average height of Moscow women, emphasizing a modern, simple style that allowed for efficient mass production. However, in the newly built apartments of the Khrushchev era, the individual kitchens were rarely up to the standards invoked by the government’s rhetoric. Providing fully fitted kitchens were too expensive and time-consuming to be realized in the mass housing project.[66]

Design of the home[edit]

The streamlined, simple design and aesthetic of the kitchen was promoted throughout the rest of the home.[67] Previous styles were labeled as petit-bourgeois once Khrushchev came to power.[68] Khrushchev denounced the ornate style of high Stalinism for its wastefulness.[69] The arrangement of the home during the Thaw emphasized that which was simple and functional, for those items could be easily mass-produced. Khrushchev promoted a culture of increased consumption and publicly announced that the per capita consumption of the Soviet Union would exceed that of the United States. However, consumption consisted of modern goods that lacked decorative qualities and were often poor quality, which spoke to the society’s emphasis on production rather than consumption.[70]

Khrushchev’s dismissal and the end of reforms[edit]

Both the cultural and the political thaws were effectively ended with the removal of Khrushchev as Soviet leader in October 1964, and the installment of Leonid Brezhnev as General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in 1964. When Khrushchev was dismissed, Alexei Kosygin took over Khrushchev’s position as Soviet Premier,[17] but Kosygin’s economic reform was not successful and hardline communists led by Brezhnev blocked any motions for reforms after Kosygin’s failed attempt.

Brezhnev’s career as General Secretary began with the Sinyavsky–Daniel trial in 1965,[17] which showed that a conservative communist ideology was being established. He approved the invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968, Vietnam War 1964-75, and the Soviet–Afghan War which continued after his death. He installed a more authoritarian regime that lasted throughout his premiership and that of his two successors, Yuri Andropov and Konstantin Chernenko.[17]

Timeline[edit]

- 1953: Stalin died. Beria eliminated by Zhukov. Khrushchev and Malenkov became leaders of the Soviet Communist Party.

- 1954: Khrushchev visited Beijing, China, met Chairman Mao Zedong. Started rehabilitation and release of Soviet political prisoners. Allowed uncensored public performances of poets and songwriters in the Soviet Union.

- 1955: Khrushchev met with US President Eisenhower. West Germany’s entry into NATO causes the Soviet Union to respond with the establishment of the Warsaw Pact. Khrushchev reconciled with Tito. Zhukov appointed Minister of Defence. Brezhnev appointed to run Virgin Lands Campaign.

- 1956: Khrushchev denounced Stalin in his Secret Speech. Hungarian Revolution crushed by the Soviet Army. Ended Polish uprising earlier that year by granting some concessions, i.e. removal of some troops.

- 1957: Coup against Khrushchev. Old Guard ousted from Kremlin. World Festival of Youth and Students in Moscow. Tape recorders spread popular music all over the Soviet State. Sputnik orbited the Earth. Introduced sovnarkhozes.

- 1958: Khrushchev named premier of the Soviet Union, ousted Zhukov from Minister of Defence, cut military spending, (Councils of People’s Economy). 1st International Tchaikovsky Competition in Moscow.

- 1959: Khrushchev visited the US. Unsuccessful introduction of maize during agricultural crisis in the Soviet Union caused serious food crisis. Sino-Soviet split started.

- 1960: Kennedy elected President of the USA. Vietnam War escalated. American U–2 spy plane shot down over the Soviet Union. Pilot Powers pleaded guilty. Khrushchev cancelled the summit with Eisenhower.

- 1961: Stalin’s body removed from Lenin’s mausoleum. Yuri Gagarin became the first man in space. Khrushchev approved the Berlin Wall. The Soviet rouble redenominated 10:1, food crisis continued.

- 1962: Khrushchev and Kennedy struggled through the Cuban Missile Crisis. Food crisis caused the Novocherkassk massacre. First publication about the «Gulag» camps by Solzhenitsyn.

- 1963: Valentina Tereshkova became the first woman in space. Ostankino TV tower construction started. Treaty banning Nuclear Weapon Tests signed. Kennedy assassinated. Khrushchev hosted Fidel Castro in Moscow.

- 1964: Beatlemania came to the Soviet Union, music bands formed at many Russian schools. 40 bugs found in the US Embassy in Moscow. Brezhnev ousted Khrushchev, and placed him under house arrest.

History repeated[edit]

Many historians compare Khrushchev’s Thaw and his massive efforts to change the Soviet society and move away from its past, with Gorbachev’s perestroika[17] and glasnost during the 1980s. Although they led the Soviet Union in different eras, both Khrushchev and Gorbachev had initiated dramatic reforms. Both efforts lasted only a few years and were supported by the people, while being opposed by the hard-liners. Both leaders were dismissed, albeit with completely different results for their country.

Mikhail Gorbachev has called Khrushchev’s achievements remarkable; he praised Khrushchev’s 1956 speech, but stated that Khrushchev did not succeed in his reforms.[25]

See also[edit]

- Cuban Thaw

- Economic reforms in 1957 (Russian Wikipedia)

- Era of Stagnation

- Goulash Communism

- Polish October (Gomułka Thaw)

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u William Taubman, Khrushchev: The Man and His Era, London: Free Press, 2004

- ^ Joseph Stalin killer file Archived August 3, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ilya Ehrenburg (1954). «Оттепель» [The Thaw (text in original Russian)]. lib.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 10 October 2004.

- ^ Tompson, William J. Khrushchev: A Political Life. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1995

- ^ Khrushchev, Sergei N., translated by William Taubman, Khrushchev on Khrushchev, Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1990.

- ^ Rettie, John. «How Khrushchev Leaked his Secret Speech to the World», Hist Workshop J. 2006; 62: 187–193.

- ^ Stites, Richard (1992). Russian Popular Culture: Entertainment and Society Since 1900. Cambridge University Press. pp. 123–53. ISBN 052136986X. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- ^ Khrushchev, Sergei N., Nikita Khrushchev and the Creation of a Superpower, Penn State Press, 2000.

- ^ Schecter, Jerrold L, ed. and trans., Khrushchev Remembers: The Glasnost Tapes, Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1990

- ^ a b c d e Dmitri Volkogonov. Stalin: Triumph and Tragedy, 1996, ISBN 0-7615-0718-3

- ^ The most secretive people (in Russian): Зенькович Н. Самые закрытые люди. Энциклопедия биографий. М., изд. ОЛМА-ПРЕСС Звездный мир, 2003 г. ISBN 5-94850-342-9

- ^ a b c Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn (1974). The Gulag Archipelago. Harper & Row. ISBN 978-0060007768.

- ^ Georgy Zhukov’s Memoirs: Marshal G.K. Zhukov, Memoirs, Moscow, Olma-Press, 2002

- ^ a b c d e f g Strobe Talbott, ed., Khrushchev Remembers (2 vol., tr. 1970–74)

- ^ Vladimir Karpov. (Russian source: Маршал Жуков: Опала, 1994) Moscow, Veche publication.

- ^ World Affairs. Leonid Brezhnev.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Russian source: Factbook on the history of the Communist Party and the Soviet Union. Справочник по истории Коммунистической партии и Советского Союза 1898 — 1991 Archived 2010-08-14 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Cohen, Stephen F. (2011). The Victims Return: Survivors of the Gulag After Stalin. London: I. B. Tauris & Company. pp. 89–91. ISBN 9781848858480.

- ^ Stalin’s Terror: High Politics and Mass Repression in the Soviet Union by Barry McLoughlin and Kevin McDermott (eds). Palgrave Macmillan, 2002, p. 6

- ^ Nahaylo, Bohdan; Swoboda, Victor (1990), Soviet disunion: a history of the nationalities problem in the USSR, p. 120. Free Press, ISBN 0-02-922401-2

- ^ Suny, Ronald Grigor (1994), The Making of the Georgian Nation, pp. 303-305. Indiana University Press, ISBN 0-253-20915-3

- ^ Gati, Charles (2006). Failed Illusions: Moscow, Washington, Budapest and the 1956 Hungarian Revolt. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-5606-6.

- ^ Stalinism in Poland, 1944-1956, ed. and tr. by A. Kemp-Welch, St. Martin’s Press, New York, 1999, ISBN 0-312-22644-6.

- ^ a b c Volkogonov, Dmitri Antonovich (Author); Shukman, Harold (Editor, Translator). Autopsy for an Empire: the Seven Leaders Who Built the Soviet Regime. Free Press, 1998 (Hardcover, ISBN 0-684-83420-0); (Paperback, ISBN 0-684-87112-2)

- ^ a b Mikhail Gorbachev. The first steps towards a new era. Guardian.

- ^ Pipes, Richard. Communism: A History. Modern Library Chronicles, 2001 (hardcover, ISBN 0-679-64050-9); (2003 paperback reprint, ISBN 0-8129-6864-6)

- ^ Grutzner, Charles (October 29, 1954). «Two Soviet Scientists on Way Here For Last of Columbia Bicentennial: Soviet Will Join in Columbia Fete». The New York Times. Retrieved July 10, 2022.

- ^ Cultural Relations Between the United States and the Soviet Union: Efforts to Establish Cultural-scientific Exchange Blocked by U.S.S.R. Washington: United States Government Printing Office. 1949. p. 7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ «Columbia Hails Moscow». The New York Times. May 10, 1955. Retrieved July 18, 2022.

- ^ Zhuk, Sergei (2018). Soviet Americana: The Cultural History of Russian and Ukrainian Americanists. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-78673-303-0.

- ^ Walter L. Hixson: Parting the Curtain: Propaganda, Culture, and the Cold War, 1945-1961 (MacMillan 1997), p.117

- ^ Moscow marks 50 years since youth festival.

- ^ Van den Bercken, William. Ideology and Atheism in the Soviet Union. Walter de Gruyter. p. 114.

- ^ {{cite book

| author1-first =Alexandre

|author1-last =Bennigsen

| author2-first=S. Enders

|author2-last= Wimbush

| title =Muslims of the Soviet Empire

| year = 1985

|page=17 - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Schmelz, Peter (2009). Such freedom, if only musical: Unofficial Soviet Music during the Thaw. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. pp. 3–25.

- ^ a b Schwarz, Boris (1972). Music and Musical Life in Soviet Russia 1917-1970. New York, NY: N.W. Norton. pp. 416–439.

- ^ a b Schmelz, Peter (2009). From Scriabin to Pink Floyd The ANS Synthesizer and the Politics of Soviet Music between Thaw and Stagnation. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 254–272.

- ^ McBurney, Gerald (123–124). Soviet Music after the Death of Stalin: The Legacy of Shostakovich. Oxford: Oxford University Press Inc. pp. 123–124.

- ^ Johanna Granville, «Dej-a-Vu: Early Roots of Romania’s Independence,» Archived 2013-10-14 at the Wayback Machine East European Quarterly, vol. XLII, no. 4 (Winter 2008), pp. 365-404.

- ^ Kennedy, Robert F. Thirteen Days: A Memoir of the Cuban Missile Crisis; ISBN 0-393-31834-6.

- ^ a b Richmond, Yale, «The 1959 Kitchen Debate (or, how cultural exchanges changed the Soviet Union),» Russian Life 52, no. 4 (2009), 47.

- ^ Richmond, Yale, «The 1959 Kitchen Debate (or, how cultural exchanges changed the Soviet Union),» Russian Life 52, no. 4 (2009), 45.

- ^ Brusilovskaia, Lidiia, «The Culture of Everyday Life During the Thaw,» Russian Studies in History 48, no. 1 (2009) 19.

- ^ Reid, Susan, «Cold War in the Kitchen: Gender and the De-Stalinization of Consumer Taste in the Soviet Union under Khrushchev,» Slavic Review 61, no. 2 (2002), 242.

- ^ David Riesman as quoted in Reid, Susan, «Cold War in the Kitchen: Gender and the De-Stalinization of Consumer Taste in the Soviet Union under Khrushchev,» Slavic Review 61, no. 2 (2002), 222.

- ^ Reid, Susan, «Cold War in the Kitchen: Gender and the De-Stalinization of Consumer Taste in the Soviet Union under Khrushchev,» Slavic Review 61, no. 2 (2002), 233.

- ^ a b Johnson, Priscilla, Khrushchev and the Arts (Cambridge: The M.I.T. Press, 1965), 102.

- ^ Reid, Susan, «Cold War in the Kitchen: Gender and the De-Stalinization of Consumer Taste in the Soviet Union under Khrushchev,» Slavic Review 61, no. 2 (2002), 237.

- ^ Reid, Susan, «Cold War in the Kitchen: Gender and the De-Stalinization of Consumer Taste in the Soviet Union under Khrushchev,» Slavic Review 61, no. 2 (2002), 228.

- ^ McKenzie, Brent, «The 1960s, the Central Department Store and Successful Soviet Consumerism: the Case of Tallinna Kaubamaja—Tallinn’s «Department Store», «International Journal of Interdisciplinary Social Sciences 5, no.9 (2011), 45.

- ^ McKenzie, Brent, «The 1960s, the Central Department Store and Successful Soviet Consumerism: the Case of Tallinna Kaubamaja—Tallinn’s «Department Store», «International Journal of Interdisciplinary Social Sciences 5, no.9 (2011), 41.

- ^ McKenzie, Brent, «The 1960s, the Central Department Store and Successful Soviet Consumerism: the Case of Tallinna Kaubamaja—Tallinn’s «Department Store», «International Journal of Interdisciplinary Social Sciences 5, no.9 (2011), 42.

- ^ Susan E. Reid, «The Khrushchev Kitchen: Domesticating the Scientific-Technological Revolution,» Journal of Contemporary History 40 (2005), 295.

- ^ Susan E. Reid, «Cold War in the Kitchen: Gender and the De-Stalinization of Consumer Taste in the Soviet Union under Khrushchev,» Slavic Review 61 (2002), 244.

- ^ Cold War in the Kitchen: Gender and the De-Stalinization of Consumer Taste in the Soviet Union under Khrushchev,» Slavic Review 61.2 (2002): 115-16.

- ^ Lynne Attwood, «Housing in the Khrushchev Era» in Women in the Khrushchev Era, Melanie Ilic, Susan E. Reid, and Lynne Attwood, eds., (Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004), 177.

- ^ Susan E. Reid, «The Khrushchev Kitchen: Domesticating the Scientific-Technological Revolution,» Journal of Contemporary History 40 (2005), 289.

- ^ Iurii Gerchuk, «The Aesthetics of Everyday Life in the Khrushchev Thaw in the USSR (1954-64)» in Style and Socialism: Modernity and Material Culture in Post-War Eastern Europe, Susan E. Reid and David Crowley, eds., (Oxford: Berg, 2000), 88.

- ^ Natasha Kolchevska, «Angels in the Home and at Work: Russian Women in the Khrushchev Years,» Women’s Studies Quarterly 33 (2005), 115-17.

- ^ Susan E. Reid, «The Khrushchev Kitchen: Domesticating the Scientific-Technological Revolution,» Journal of Contemporary History 40 (2005), 291-94.

- ^ Susan E. Reid, «Cold War in the Kitchen: Gender and the De-Stalinization of Consumer Taste in the Soviet Union under Khrushchev,» Slavic Review 61 (2002), 224.

- ^ Susan E. Reid, «The Khrushchev Kitchen: Domesticating the Scientific-Technological Revolution,» Journal of Contemporary History 40 (2005), 289-95.

- ^ Susan E. Reid, «Cold War in the Kitchen: Gender and the De-Stalinization of Consumer Taste in the Soviet Union under Khrushchev,» Slavic Review 61 (2002), 223-24.

- ^ Susan E. Reid, «The Khrushchev Kitchen: Domesticating the Scientific-Technological Revolution,» Journal of Contemporary History 40 (2005), 290-303.

- ^ Susan E. Reid, «Cold War in the Kitchen: Gender and the De-Stalinization of Consumer Taste in the Soviet Union under Khrushchev,» Slavic Review 61 (2002), 244-49.

- ^ Susan E. Reid, «The Khrushchev Kitchen: Domesticating the Scientific-Technological Revolution,» Journal of Contemporary History 40 (2005), 315.

- ^ Susan E. Reid, «The Khrushchev Kitchen: Domesticating the Scientific-Technological Revolution,» Journal of Contemporary History 40 (2005), 308-309.

- ^ Susan E. Reid, «Women in the Home» in Women in the Khrushchev Era, Melanie Ilic, Susan E. Reid, and Lynne Attwood, eds., (Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004), 153.

- ^ Susan E. Reid, «Destalinization and Taste, 1953-1963,» Journal of Design History, 10 (1997), 177-78.

- ^ Susan E. Reid, «Cold War in the Kitchen: Gender and the De-Stalinization of Consumer Taste in the Soviet Union under Khrushchev,» Slavic Review 61 (2002), 216-243.

External links[edit]

- SovLit — Free summaries of Soviet era books, many from the Thaw Era

Денис Александрович Борисенко

Эксперт по предмету «История России»

Стать автором

Определение 1

Хрущёвская оттепель — это неофициальное название периода в советской истории после смерти И. В. Сталина, продолжавшегося десять лет с середины 1950-х до середины 1960-х годов. Он характеризуется осуждением репрессий 1930-х годов и культа личности, освобождением политических заключённых, ослаблением тоталитарной власти, ликвидацией ГУЛАГа, появлением свободы слова, либерализацией общественной и политической жизни, свободой творческой деятельности.

Началом «хрущёвской оттепели» стала смерть И.В. Сталина в 1953 году. К «оттепели» относится период (1953—1955), когда страной руководил Г. Маленков, и были закрыты уголовные дела («Дело врачей», «Ленинградское дело»), прошла амнистия по незначительным преступлениям. В системе ГУЛАГа в это время вспыхнули крупные восстания заключённых: Воркутинское, Кенгирское, Норильское.

Десталинизация

С укреплением Хрущёва у власти «оттепель» начала ассоциироваться с развенчанием культа личности. Еще в 1953—1956 годах Сталин официально продолжал почитаться великим лидером; на портретах в тот период он изображался вместе с Лениным. В 1956 году на XX съезде КПСС Хрущёв сделал доклад «О культе личности и его последствиях», подвергнув критике сталинские репрессии и культ личности, а в советской внешней политике был провозглашён курс на «сосуществование» с капиталистическим миром. Хрущёв начал курс на сближение с Югославией, связи с которой при Сталине были разорваны.

Новый курс в целом был поддержан верхами партии и соответствовал интересам номенклатуры, поскольку ранее даже самые видные партийные деятели, попавшие в опалу, боялись за свою жизнь. Многие политические заключённые в СССР были реабилитированы. В 1953 году были созданы комиссии по реабилитации. Большинству депортированных народов было разрешено вернуться на родину.

Также было смягчено трудовое законодательство. В 1956 году Верховный Совет утвердил указ президиума, отменивший судебную ответственность за уход из учреждений, и за опоздание на работу или прогул без уважительной причины.

«СССР в период «оттепели»: экономика, политика, культура.» 👇

На родину отправились тысячи немецких и японских военнопленных. К власти в некоторых странах пришли либеральные руководители (Имре Надь в Венгрии). В 1955 году в Женеве Хрущёв встретился с президентом США Д. Эйзенхауэром и главами правительств Франции и Великобритании.

Одновременно десталинизация негативно повлияла на отношения с Китаем. Китайская Коммунистическая партия осудила десталинизацию за ревизионизм.

Замечание 1

29 декабря 1958 года из Уголовного Кодекса был исключен термин «враг народа».

В хрущевский период к Сталину относились положительно-нейтрально. Во всех изданиях Сталина называли стойким революционером, деятелем партии и крупным теоретиком партии, который сплотил партию в период тяжёлых испытаний. Однако во всех изданиях тогда же писали, что Сталин имел недостатки и, что в последние годы он совершал крупные ошибки.

«Оттепель» в экономике и социальной сфере

В 1953-1956 годах повышались государственные закупочные цены на продукцию, произведенную колхозами.

В 1954 году отменялось раздельное обучение в школах.

В 1955 году отменили уголовное наказание за аборты.

С 1956 года стало бесплатным обучение в 8-10 классах средней школы и вузах.

В 1956 году сократилась продолжительность рабочего дня по субботам до шести часов. В 1960 году продолжительность рабочих дней была уменьшена до семи часов.

В 1956 году принят закон о всеобщем пенсионном обеспечении граждан. В 1964 году он был распространен на колхозников. Размер средней пенсии увеличился в два раза.

В 1957 году в Советском Союзе было развернуто массовое жилищное строительство. В 1957-1963 годах жилищный фонд вырос с 640 до 1184 млн. кв. метров жилой площади, жилищные условия были улучшены у более 50 млн. человек.

В 1957 году прекратился выпуск облигаций внутреннего государственного займа, ранее распространявшихся принудительно среди населения.

В 1958 году был отменен налог на бездетность для незамужних женщин.

В 1959 году законодательно разрешили потребительские кредиты населению под покупку товаров длительного пользования.

Объём бытовых услуг увеличился в десятки раз за счёт пунктов проката бытовой техники и строительства домов быта.

«Оттепель» в искусстве

Во время десталинизации ослабела цензура. «Поэтическим бестселлером» эпохи стал стихотворный сборник Л. Мартынова. Платформой для сторонников «оттепели» служил литературный журнал «Новый мир». Некоторые произведения стали известны и за рубежом (повесть А. Солженицына «Один день Ивана Денисовича» и роман В. Дудинцева «Не хлебом единым»). Другими представителями «оттепели» были:

- В. Астафьев;

- Б. Ахмадулина;

- В. Тендряков;

- А. Вознесенский;

- Р. Рождественский;

- Е. Евтушенко.

Резко увеличилось производство кинофильмов. Григорий Чухрай затронул тему десталинизации в фильме «Чистое небо» (1961). Ключевые кинорежиссёры периода:

- Г. Данелия;

- Э. Рязанов;

- М. Хуциев;

- М. Ромм;

- Л. Гайдай.

В 1957 году в Москве проходил VI Всемирный фестиваль молодёжи студентов.

Конец «оттепели»

Концом «оттепели» считается приход к руководству страной Леонида Брежнева в 1964 году. Однако ужесточение режима и идеологического контроля началось ещё в период правления Хрущёва после Карибского кризиса. Десталинизация приостановилась, а во время празднования 20-й годовщины Победы начался процесс возвеличивания роли победы народа в войне. Личность Сталина обходилась стороной. В 1976 году в третьем издании Большой советской энциклопедии о нём осталась нейтральная статья. По случаю столетия Сталина в 1979 году вышло несколько статей, однако особых торжеств не устраивалось.

Массовые репрессии не были возобновлены, а утративший власть Хрущёв просто ушёл на пенсию. Перед этим Хрущёв раскритиковал термин «оттепель» и назвал Эренбурга «жуликом».

Замечание 2

Многие исследователи полагают, что оттепель окончательно закончилась в 1968 году с подавлением Пражской весны.

Находи статьи и создавай свой список литературы по ГОСТу

Поиск по теме

Первые радикальные шаги Хрущева – критика культа личности Сталина и другие политические изменения.

Эпоху Хрущева называют «оттепелью» — периодом смягчения тоталитарного режима, предоставлением некоторых свобод во всех сферах жизни общества. «Оттепель» произошла и в политической сфере.

Одной из идей Хрущева (как и Берии с Маленковым) была идея критики культа личности Сталина.

В 1956 году состоялся XX съезд КПСС, на котором с докладом «О культе личности и его последствиях» выступил Первый секретарь ЦК Н. С. Хрущёв. Он обвинил своего предшественника в развязывании массовых репрессий, в установлении единовластия, которое привело к тяжким последствиям в ходе Великой Отечественной войны и во многом другом.

Доклад Хрущева вызвал потрясение и сомнение у слушателей. Развенчание культа личности вождя народов имел, с одной стороны, положительный эффект и последствия.

-

Впервые было сказано о незаконном характере репрессий 1930-1940-х годов, что демократизировало общественное мнение, раскрепостило его.

-

Начался еще более масштабный, чем при Берии, процесс реабилитации жертв сталинских репрессий (так, были реабилитированы целые народы – в 1957 году Верховный совет СССР разрешил вернуться на историческое место жительства репрессированным и выселенным в годы войны калмыкам, чеченцам, ингушам)

-

В 1956 году ЦК КПСС выпустило постановление «О преодолении культа личности и его последствиях», который был прочитан на партийных собраниях по всей стране. Люди избавились от страха, произошло раскрепощение сознания.

-

За политическими изменениями последовали и культурные – была ослаблена цензура, начали печататься те произведения, что были запрещены в сталинскую эпоху. Атмосфера «оттепели», десталинизация сформировала поколение советских граждан, названных «шестидесятниками», которые сохранили дух и ценности этого либерального десятилетия.

Однако были и негативные черты десталинизации.

-

Выступление Хрущева раскололо общество на сторонников и противников разоблачения культа личности.

-

Ухудшились отношения со странами социалистического лагеря (например, произошло охлаждение отношений с Китаем, где в это время Мао Цзэдун создавал свой собственный культ личности).

-

Десталинизация, начавшаяся в 1950-х годах, не была завершена. В середине 1960-х годов она была свернута, начали предприниматься попытки пересмотреть решения XX съезда КПСС.

Руководство СССР не понимало или не хотело понимать того, что истоки преступлений сталинского режима кроются в существующей политической системе. Вопрос о проблемах системы не ставился в принципе. Во всем винился один конкретный человек — Сталин, что было, конечно, далеко не объективно.

Помимо развенчания культа личности, в политической сфере хрущевской эпохи произошли и другие изменения. На XXII съезде КПСС в 1961 году была принята программа построения коммунизма в СССР к 1980 году. Для построения коммунизма предполагалось решить три задачи:

-

построить материально-техническую базу коммунизма (достигнуть наивысшей в мире производительности труда и обеспечить самый высокий жизненный уровень населения);

-

перейти к коммунистическому самоуправлению (повысить инициативу на местах, избавиться от чрезмерной бюрократизации);

-

воспитать нового, всесторонне развитого человека.

Развитие сельского хозяйства:

Еще Маленков в 1953 году на сессии Верховного Совета заговорил о развитии сельского хозяйства. Хрущев, избранный в сентябре 1953 Первым секретарем, подхватил эту идею.

В период с 1953 по 1958 были проведены следующие экономические реформы:

Повышение закупочных цен на те товары, которые колхозники должны были принудительно продавать государству, списание с колхозов долгов за прошлые года и увеличение финансирования деревни.

Итог: повышение закупочных цен все равно не смогло компенсировать всех затрат производства, но цены стали более обоснованными; это повысило благосостояние колхозников.

Введение паспортов, появление пенсий для колхозников, ликвидация налогов на ЛПХ (личное приусадебное хозяйство) и разрешение его увеличить.

Итог: демократизация деревни, повышение благосостояния колхозников за счет расширения личного огорода (ЛПХ).

Направление 30 тысяч партийных работников в слабые колхозы для укрепления руководящих кадров и увеличения колхозного производства (так называемое движение «тридцатитысячников»).

Итог: тридцатитысячники были поставлены председателями колхозов, пытались административными методами увеличить производительность колхозов (эти действия были более-менее успешны).

Реорганизация машинно-тракторных станций (МТС) в ремонтно-тракторные станции (РТС) и продажа техники колхозам. Трактора и комбайны не отдали колхозникам, а заставили их выкупить эту технику в сжатые сроки (за год) по высоким ценам.

Итоги: финансовые трудности в колхозах, отъезд технических кадров в город (так как раньше работники МТС считались рабочими, а после реорганизации МТС в РТС они бы стали считаться колхозниками и лишились бы своих преимуществ).

Освоение целинных (то, что никогда не обрабатывалось, не пахалось) и залежных (те участки, что раньше пахали, но давно забросили) земель.

Итоги: освоение целины дало 42 миллиона га новых полей. Но экстенсивный путь развития сельского хозяйства (увеличение производства за счет новых посевных площадей, а не путем улучшения технологии и/или использования передовой техники) привел только к временному результату.

Но такие либеральные реформы продолжались лишь до 1958 года. В конце 1950-х годов началось навое закручивание гаек. Колхозы, финансово ослабленные после принудительной скупки МТС в свою собственность, испытали на себе новый административный нажим.

ЛПХ начали уменьшать в размерах, так как это, по мнению партийных деятелей, порождало собственнические интересы и препятствовало построению коммунизма на деревне.

Итог: сокращение личных огородов и садов негативно отразилось на экономическом благосостоянии отдельных жителей.

Стремление к увеличению заготовок мяса обусловило призыв Хрущева продавать личный скот колхозу, а взамен покупать у этого же колхоза (или получать за трудодни) мясо-молочную продукцию.

Итог: убой молочных коров (деревенские жители забивали скот, чтобы не продавать его колхозам, а побыстрее съесть самим), изымание скота у населения и как следствие — резкое снижение поголовья скота в СССР.