During World War I, the German Empire was one of the Central Powers. It began participation in the conflict after the declaration of war against Serbia by its ally, Austria-Hungary. German forces fought the Allies on both the eastern and western fronts, although German territory itself remained relatively safe from widespread invasion for most of the war, except for a brief period in 1914 when East Prussia was invaded. A tight blockade imposed by the Royal Navy caused severe food shortages in the cities, especially in the winter of 1916–17, known as the Turnip Winter. At the end of the war, Germany’s defeat and widespread popular discontent triggered the German Revolution of 1918–1919 which overthrew the monarchy and established the Weimar Republic.

Overview[edit]

The German population responded to the outbreak of war in 1914 with a complex mix of emotions, in a similar way to the populations in other countries of Europe; notions of overt enthusiasm known as the Spirit of 1914 have been challenged by more recent scholarship.[1] The German government, dominated by the Junkers, saw the war as a way to end being surrounded by hostile powers France, Russia and Britain. The war was presented inside Germany as the chance for the nation to secure «our place under the sun,» as the Foreign Minister Bernhard von Bülow had put it, which was readily supported by prevalent nationalism among the public. The German establishment hoped the war would unite the public behind the monarchy, and lessen the threat posed by the dramatic growth of the Social Democratic Party of Germany, which had been the most vocal critic of the Kaiser in the Reichstag before the war. Despite its membership in the Second International, the Social Democratic Party of Germany ended its differences with the Imperial government and abandoned its principles of internationalism to support the war effort. The German state spent 170 billion Marks during the war. The money was raised by borrowing from banks and from public bond drives. Symbolic purchasing of nails which were driving into public wooden crosses spurred the aristocracy and middle class to buy bonds. These bonds became worthless with the 1923 hyperinflation.

It soon became apparent that Germany was not prepared for a war lasting more than a few months. At first, little was done to regulate the economy for a wartime footing, and the German war economy would remain badly organized throughout the war. Germany depended on imports of food and raw materials, which were stopped by the British blockade of Germany. First food prices were limited, then rationing was introduced. In 1915 five million pigs were massacred in the so-called Schweinemord, both to produce food and to preserve grain. The winter of 1916/17 was called the «turnip winter» because the potato harvest was poor and people ate animal food, including vile-tasting turnips. From August 1914 to mid-1919, the excess deaths compared to peacetime caused by malnutrition and high rates of exhaustion and disease and despair came to about 474,000 civilians.[2][3]

Government[edit]

According to biographer Konrad H. Jarausch, a primary concern for Bethmann Hollweg in July 1914 was the steady growth of Russian power, and the growing closeness of the British and French military collaboration. Under these circumstances he decided to run what he considered a calculated risk to back Vienna in a local small-scale war against Serbia, while risking a major war with Russia. He calculated that France would not support Russia. It failed when Russia decided on general mobilization, and his own Army demanded the opportunity to use the Schlieffen Plan for quick victory against a poorly prepared France. By rushing through Belgium, Germany expanded the war to include England. Bethmann thus failed to keep France and Britain out of the conflict.[5]

The crisis came to a head on 5 July 1914 when the Count Hoyos Mission arrived in Berlin in response to Austro-Hungarian Foreign Minister Leopold Berchtold’s plea for friendship. Bethmann Hollweg was assured that Britain would not intervene in the frantic diplomatic rounds across the European powers. However, reliance on that assumption encouraged Austria to demand Serbian concessions. His main concern was Russian border manoeuvres, conveyed by his ambassadors at a time when Raymond Poincaré himself was preparing a secret mission to St Petersburg. He wrote to Count Sergey Sazonov, «Russian mobilisation measures would compel us to mobilise and that then European war could scarcely be prevented.»[6]

Following the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo on 28 June 1914, Bethmann Hollweg and his foreign minister, Gottlieb von Jagow, were instrumental in assuring Austria-Hungary of Germany’s unconditional support, regardless of Austria’s actions against Serbia. While Grey was suggesting a mediation between Austria-Hungary and Serbia, Bethmann Hollweg wanted Austria-Hungary to attack Serbia and so he tampered with the British message and deleted the last line of the letter: «Also, the whole world here is convinced, and I hear from my colleagues that the key to the situation lies in Berlin, and that if Berlin seriously wants peace, it will prevent Vienna from following a foolhardy policy.[7]

When the Austro-Hungarian ultimatum was presented to Serbia, Kaiser Wilhelm II ended his vacation and hurried back to Berlin.

When Wilhelm arrived at the Potsdam station late in the evening of July 26, he was met by a pale, agitated, and somewhat fearful Chancellor. Bethmann Hollweg’s apprehension stemmed not from the dangers of the looming war, but rather from his fear of the Kaiser’s wrath when the extent of his deceptions were revealed. The Kaiser’s first words to him were suitably brusque: «How did it all happen?» Rather than attempt to explain, the Chancellor offered his resignation by way of apology. Wilhelm refused to accept it, muttering furiously, «You’ve made this stew, now you’re going to eat it!»[8]

Bethmann Hollweg, much of whose foreign policy before the war had been guided by his desire to establish good relations with Britain, was particularly upset by Britain’s declaration of war following the German violation of Belgium’s neutrality during its invasion of France. He reportedly asked the departing British Ambassador Edward Goschen how Britain could go to war over a «scrap of paper» («ein Fetzen Papier«), which was the 1839 Treaty of London guaranteeing Belgium’s neutrality.

Bethmann Hollweg sought public approval from a declaration of war. His civilian colleagues pleaded for him to register some febrile protest, but he was frequently outflanked by the military leaders, who played an increasingly important role in the direction of all German policy.[9] However, according to historian Fritz Fischer, writing in the 1960s, Bethmann Hollweg made more concessions to the nationalist right than had previously been thought. He supported the ethnic cleansing of Poles from the Polish Border Strip as well as Germanisation of Polish territories by settlement of German colonists.[10]

A few weeks after the war began Bethmann presented the Septemberprogramm, which was a survey of ideas from the elite should Germany win the war. Bethmann Hollweg, with all credibility and power now lost, conspired over Falkenhayn’s head with Paul von Hindenburg and Erich Ludendorff (respectively commander-in-chief and chief of staff for the Eastern Front) for an Eastern Offensive. They then succeeded, in August 1916 in securing Falkenhayn’s replacement by Hindenburg as Chief of the General Staff, with Ludendorff as First Quartermaster-General (Hindenburg’s deputy). Thereafter, Bethmann Hollweg’s hopes for US President Woodrow Wilson’s mediation at the end of 1916 came to nothing. Over Bethmann Hollweg’s objections, Hindenburg and Ludendorff forced the adoption of unrestricted submarine warfare in March 1917, adopted as a result of Henning von Holtzendorff’s memorandum. Bethmann Hollweg had been a reluctant participant and opposed it in cabinet. The US entered the war in April 1917.

According to Wolfgang J. Mommsen, Bethmann Hollweg weakened his own position by failing to establish good control over public relations. To avoid highly intensive negative publicity, he conducted much of his diplomacy and secret, thereby failed to build strong support for it. In 1914 he was willing to risk a world war to win public support.[11]

Bethmann Hollweg remained in office until July 1917, when a Reichstag revolt resulted in the passage of Matthias Erzberger’s Peace Resolution by an alliance of the Social Democratic, Progressive, and Centre parties. That same July the strong opposition to him from high-level military leaders – including Hindenburg and Ludendorff who both threatened to resign – was exacerbated when Bethmann Hollweg convinced the Emperor to agree publicly to the introduction of equal manhood suffrage in Prussian state elections.[12] The combination of political and military opposition forced Bethmann Hollweg’s resignation and replacement by a relatively unknown figure, Georg Michaelis.[13]

1914–15[edit]

The German army opened the war on the Western Front with a modified version of the Schlieffen Plan, designed to quickly attack France through neutral Belgium before turning southwards to encircle the French army on the German border. The Belgians fought back, and sabotaged their rail system to delay the Germans. The Germans did not expect this and were delayed, and responded with systematic reprisals on civilians, killing nearly 6,000 Belgian noncombatants, including women and children, and burning 25,000 houses and buildings.[14] The plan called for the right flank of the German advance to converge on Paris and initially, the Germans were very successful, particularly in the Battle of the Frontiers (14–24 August). By 12 September, the French with assistance from the British forces halted the German advance east of Paris at the First Battle of the Marne (5–12 September). The last days of this battle signified the end of mobile warfare in the west. The French offensive into Germany launched on 7 August with the Battle of Mulhouse had limited success.[15]

In the east, only one Field Army defended East Prussia and when Russia attacked in this region it diverted German forces intended for the Western Front. Germany defeated Russia in a series of battles collectively known as the First Battle of Tannenberg (17 August – 2 September), but this diversion exacerbated problems of insufficient speed of advance from rail-heads not foreseen by the German General Staff. The Central Powers were thereby denied a quick victory and forced to fight a war on two fronts. The German army had fought its way into a good defensive position inside France and had permanently incapacitated 230,000 more French and British troops than it had lost itself. Despite this, communications problems and questionable command decisions cost Germany the chance of obtaining an early victory.

1916[edit]

1916 was characterized by two great battles on the Western front, at Verdun and the Somme. They each lasted most of the year, achieved minimal gains, and drained away the best soldiers of both sides. Verdun became the iconic symbol of the murderous power of modern defensive weapons, with 280,000 German casualties, and 315,000 French. At the Somme, there were over 400,000 German casualties, against over 600,000 Allied casualties. At Verdun, the Germans attacked what they considered to be a weak French salient which nevertheless the French would defend for reasons of national pride. The Somme was part of a multinational plan of the Allies to attack on different fronts simultaneously. German woes were also compounded by Russia’s grand «Brusilov offensive», which diverted more soldiers and resources. Although the Eastern front was held to a standoff and Germany suffered fewer casualties than their allies with ~150,000 of the ~770,000 Central powers casualties, the simultaneous Verdun offensive stretched the German forces committed to the Somme offensive. German experts are divided in their interpretation of the Somme. Some say it was a standoff, but most see it as a British victory and argue it marked the point at which German morale began a permanent decline and the strategic initiative was lost, along with irreplaceable veterans and confidence.[16]

1917[edit]

In early 1917 the SPD leadership became concerned about the activity of its anti-war left-wing which had been organising as the Sozialdemokratische Arbeitsgemeinschaft (SAG, «Social Democratic Working Group»). On 17 January they expelled them, and in April 1917 the left-wing went on to form the Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany (German: Unabhängige Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands). The remaining faction was then known as the Majority Social Democratic Party of Germany. This happened as the enthusiasm for war faded with the enormous numbers of casualties, the dwindling supply of manpower, the mounting difficulties on the homefront, and the never-ending flow of casualty reports. A grimmer and grimmer attitude began to prevail amongst the general population. The only highlight was the first use of mustard gas in warfare, in the Battle of Ypres.

After, morale was helped by victories against Serbia, Greece, Italy, and Russia which made great gains for the Central Powers. Morale was at its greatest since 1914 at the end of 1917 and beginning of 1918 with the defeat of Russia following her rise into revolution, and the German people braced for what General Erich Ludendorff said would be the «Peace Offensive» in the west.[17][18]

1918[edit]

In spring 1918, Germany realized that time was running out. It prepared for the decisive strike with new armies and new tactics, hoping to win the war on the Western front before millions of American soldiers appeared in battle. General Erich Ludendorff and Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg had full control of the army, they had a large supply of reinforcements moved from the Eastern front, and they trained storm troopers with new tactics to race through the trenches and attack the enemy’s command and communications centers. The new tactics would indeed restore mobility to the Western front, but the German army was too optimistic.

During the winter of 1917-18 it was «quiet» on the Western Front—British casualties averaged «only» 3,000 a week. Serious attacks were impossible in the winter because of the deep caramel-thick mud. Quietly the Germans brought in their best soldiers from the eastern front, selected elite storm troops, and trained them all winter in the new tactics. With stopwatch timing, the German artillery would lay down a sudden, fearsome barrage just ahead of its advancing infantry. Moving in small units, firing light machine guns, the stormtroopers would bypass enemy strongpoints, and head directly for critical bridges, command posts, supply dumps and, above all, artillery batteries. By cutting enemy communications they would paralyze response in the critical first half hour. By silencing the artillery they would break the enemy’s firepower. Rigid schedules sent in two more waves of infantry to mop up the strong points that had been bypassed. The shock troops frightened and disoriented the first line of defenders, who would flee in panic. In one instance an easy-going Allied regiment broke and fled; reinforcements rushed in on bicycles. The panicky men seized the bikes and beat an even faster retreat. The stormtrooper tactics provided mobility, but not increased firepower. Eventually—in 1939 and 1940—the formula would be perfected with the aid of dive bombers and tanks, but in 1918 the Germans lacked both.[19]

Ludendorff erred by attacking the British first in 1918, instead of the French. He mistakenly thought the British to be too uninspired to respond rapidly to the new tactics. The exhausted, dispirited French perhaps might have folded. The German assaults on the British were ferocious—the largest of the entire war. At the Somme River in March, 63 divisions attacked in a blinding fog. No matter, the German lieutenants had memorized their maps and their orders. The British lost 270,000 men, fell back 40 miles, and then held. They quickly learned how to handle the new German tactics: fall back, abandon the trenches, let the attackers overextend themselves, and then counterattack. They gained an advantage in firepower from their artillery and from tanks used as mobile pillboxes that could retreat and counterattack at will. In April Ludendorff hit the British again, inflicting 305,000 casualties—but he lacked the reserves to follow up. Ludendorff launched five great attacks between March and July, inflicting a million British and French casualties. The Western Front now had opened up—the trenches were still there but the importance of mobility now reasserted itself. The Allies held. The Germans suffered twice as many casualties as they inflicted, including most of their precious stormtroopers. The new German replacements were under-aged youth or embittered middle-aged family men in poor condition. They were not inspired by the elan of 1914, nor thrilled with battle—they hated it, and some began talking of revolution. Ludendorff could not replace his losses, nor could he devise a new brainstorm that might somehow snatch victory from the jaws of defeat. The British likewise were bringing in reinforcements from the whole Empire, but since their home front was in good condition, and since they could see inevitable victory, their morale was higher. The great German spring offensive was a race against time, for everyone could see the Americans were training millions of fresh young men who would eventually arrive on the Western Front.[20][21]

The attrition warfare now caught up to both sides. Germany had used up all the best soldiers they had, and still had not conquered much territory. The British likewise were bringing in youths of 18 and unfit and middle-aged men, but they could see the Americans arriving steadily. The French had also nearly exhausted their manpower. Berlin had calculated it would take months for the Americans to ship all their men and equipment—but the U.S. troops arrived much sooner, as they left their heavy equipment behind, and relied on British and French artillery, tanks, airplanes, trucks and equipment. Berlin also assumed that Americans were fat, undisciplined and unaccustomed to hardship and severe fighting. They soon realized their mistake. The Germans reported that «The qualities of the [Americans] individually may be described as remarkable. They are physically well set up, their attitude is good… They lack at present only training and experience to make formidable adversaries. The men are in fine spirits and are filled with naive assurance.»[22]

By September 1918, the Central Powers were exhausted from fighting, the American forces were pouring into France at a rate of 10,000 a day, the British Empire was mobilised for war peaking at 4.5 million men and 4,000 tanks on the Western Front. The decisive Allied counteroffensive, known as the Hundred Days Offensive, began on 8 August 1918—what Ludendorff called the «Black Day of the German army.» The Allied armies advanced steadily as German defenses faltered.[23]

Although German armies were still on enemy soil as the war ended, the generals, the civilian leadership—and indeed the soldiers and the people—knew all was hopeless. They started looking for scapegoats. The hunger and popular dissatisfaction with the war precipitated revolution throughout Germany. By 11 November Germany had virtually surrendered, the Kaiser and all the royal families had abdicated, and the German Empire had been replaced by the Weimar Republic.

Home front[edit]

War fever[edit]

The «spirit of 1914» was the overwhelming, enthusiastic support of all elements of the population for war in 1914. In the Reichstag, the vote for credits was unanimous, with all the Socialists but one (Karl Liebknecht) joining in. One professor testified to a «great single feeling of moral elevation of soaring of religious sentiment, in short, the ascent of a whole people to the heights.»[24] At the same time, there was a level of anxiety; most commentators predicted the short victorious war – but that hope was dashed in a matter of weeks, as the invasion of Belgium bogged down and the French Army held in front of Paris. The Western Front became a killing machine, as neither army moved more than a few hundred yards at a time. Industry in late 1914 was in chaos, unemployment soared while it took months to reconvert to munitions productions. In 1916, the Hindenburg Program called for the mobilization of all economic resources to produce artillery, shells, and machine guns. Church bells and copper roofs were ripped out and melted down.[25]

According to historian William H. MacNeil:

- By 1917, after three years of war, the various groups and bureaucratic hierarchies which had been operating more or less independently of one another in peacetime (and not infrequently had worked at cross purposes) were subordinated to one (and perhaps the most effective) of their number: the General Staff. Military officers controlled civilian government officials, the staffs of banks, cartels, firms, and factories, engineers and scientists, workingmen, farmers-indeed almost every element in German society; and all efforts were directed in theory and in large degree also in practice to forwarding the war effort.[26]

Economy[edit]

Germany had no plans for mobilizing its civilian economy for the war effort, and no stockpiles of food or critical supplies had been made. Germany had to improvise rapidly. All major political sectors initially supported the war, including the Socialists.

Early in the war industrialist Walter Rathenau held senior posts in the Raw Materials Department of the War Ministry, while becoming chairman of AEG upon his father’s death in 1915. Rathenau played the key role in convincing the War Ministry to set up the War Raw Materials Department (Kriegsrohstoffabteilung — ‘KRA’); he was in charge of it from August 1914 to March 1915 and established the basic policies and procedures. His senior staff were on loan from industry. KRA focused on raw materials threatened by the British blockade, as well as supplies from occupied Belgium and France. It set prices and regulated the distribution to vital war industries. It began the development of ersatz raw materials. KRA suffered many inefficiencies caused by the complexity and selfishness KRA encountered from commerce, industry, and the government.[27][28]

While the KRA handled critical raw materials, the crisis over food supplies grew worse. The mobilization of so many farmers and horses, and the shortages of fertilizer, steadily reduced the food supply. Prisoners of war were sent to work on farms, and many women and elderly men took on work roles. Supplies that had once come in from Russia and Austria were cut off.[29]

The concept of «total war» in World War I, meant that food supplies had to be redirected towards the armed forces and, with German commerce being stopped by the British blockade, German civilians were forced to live in increasingly meager conditions. Food prices were first controlled. Bread rationing was introduced in 1915 and worked well; the cost of bread fell. Allen says there were no signs of starvation and states, «the sense of domestic catastrophe one gains from most accounts of food rationing in Germany is exaggerated.»[30] However Howard argues that hundreds of thousands of civilians died from malnutrition—usually from a typhus or a disease their weakened body could not resist. (Starvation itself rarely caused death.)[31] A 2014 study, derived from a recently discovered dataset on the heights and weights of German children between 1914 and 1924, found evidence that German children suffered from severe malnutrition during the blockade, with working-class children suffering the most.[32] The study furthermore found that German children quickly recovered after the war due to a massive international food aid program.[32]

Conditions deteriorated rapidly on the home front, with severe food shortages reported in all urban areas. The causes involved the transfer of so many farmers and food workers into the military, combined with the overburdened railroad system, shortages of coal, and the British blockade that cut off imports from abroad. The winter of 1916–1917 was known as the «turnip winter,» because that hardly-edible vegetable, usually fed to livestock, was used by people as a substitute for potatoes and meat, which were increasingly scarce. Thousands of soup kitchens were opened to feed the hungry people, who grumbled that the farmers were keeping the food for themselves. Even the army had to cut the rations for soldiers.[33] Morale of both civilians and soldiers continued to sink.

The drafting of miners reduced the main energy source, coal. The textile factories produced Army uniforms, and warm clothing for civilians ran short. The device of using ersatz materials, such as paper and cardboard for cloth and leather proved unsatisfactory. Soap was in short supply, as was hot water. All the cities reduced tram services, cut back on street lighting, and closed down theaters and cabarets.

The food supply increasingly focused on potatoes and bread, it was harder and harder to buy meat. The meat ration in late 1916 was only 31% of peacetime, and it fell to 12% in late 1918. The fish ration was 51% in 1916, and none at all by late 1917. The rations for cheese, butter, rice, cereals, eggs and lard were less than 20% of peacetime levels.[34] In 1917 the harvest was poor all across Europe, and the potato supply ran short, and Germans substituted almost inedible turnips; the «turnip winter» of 1916–17 was remembered with bitter distaste for generations.[35] Early in the war bread rationing was introduced, and the system worked fairly well, albeit with shortfalls during the Turnip Winter and summer of 1918. White bread used imported flour and became unavailable, but there was enough rye or rye-potato flour to provide a minimal diet for all civilians.[36]

German women were not employed in the Army, but large numbers took paid employment in industry and factories, and even larger numbers engaged in volunteer services. Housewives were taught how to cook without milk, eggs or fat; agencies helped widows find work. Banks, insurance companies and government offices for the first time hired women for clerical positions. Factories hired them for unskilled labor – by December 1917, half the workers in chemicals, metals, and machine tools were women. Laws protecting women in the workplace were relaxed, and factories set up canteens to provide food for their workers, lest their productivity fall off. The food situation in 1918 was better, because the harvest was better, but serious shortages continued, with high prices, and a complete lack of condiments and fresh fruit. Many migrants had flocked into cities to work in industry, which made for overcrowded housing. Reduced coal supplies left everyone in the cold. Daily life involved long working hours, poor health, and little or no recreation, and increasing fears for the safety of loved ones in the Army and in prisoner of war camps. The men who returned from the front were those who had been permanently crippled; wounded soldiers who had recovered were sent back to the trenches.[37]

Defeat and revolt[edit]

Many Germans wanted an end to the war and increasing numbers of Germans began to associate with the political left, such as the Social Democratic Party and the more radical Independent Social Democratic Party which demanded an end to the war. The third reason was the entry of the United States into the war in April 1917, which tipped the long-run balance of power even more to the Allies.

The end of October 1918, in Kiel, in northern Germany, saw the beginning of the German Revolution of 1918–19. Civilian dock workers led a revolt and convinced many sailors to join them; the revolt quickly spread to other cities. Meanwhile, Hindenburg and the senior generals lost confidence in the Kaiser and his government.

In November 1918, with internal revolution, a stalemated war, Bulgaria and the Ottoman Empire suing for peace, Austria-Hungary falling apart from multiple ethnic tensions, and pressure from the German high command, the Kaiser and all German ruling princes abdicated. On 9 November 1918, the Social Democrat Philipp Scheidemann proclaimed a Republic. The new government led by the German Social Democrats called for and received an armistice on 11 November 1918; in practice it was a surrender, and the Allies kept up the food blockade to guarantee an upper hand in negotiations. The now defunct German Empire was succeeded by the Weimar Republic.[38][page needed]

7 million soldiers and sailors were quickly demobilized, and they became a conservative voice that drowned out the radical left in cities such as Kiel and Berlin. The radicals formed the Spartakusbund and later the Communist Party of Germany.

Due to German military forces still occupying portions of France on the day of the armistice, various nationalist groups and those angered by the defeat in the war shifted blame to civilians; accusing them of betraying the army and surrendering. This contributed to the «Stab-in-the-back myth» that dominated German politics in the 1920s and created a distrust of democracy and the Weimar government.[39]

War deaths[edit]

Out of a population of 65 million, Germany suffered 1.7 million military deaths and 430,000 civilian deaths due to wartime causes (especially the food blockade), plus about 17,000 killed in Africa and the other overseas colonies.[40]

The Allied blockade continued until July 1919, causing severe additional hardships.[41]

Soldiers’ experiences[edit]

Despite the often ruthless conduct of the German military machine, in the air and at sea as well as on land, individual German and soldiers could view the enemy with respect and empathy and the war with contempt.[42] Some examples from letters homework :

«A terrible picture presented itself to me. A French and a General soldier on their knees were leaning against each other. They had pierced each other with the bayonet and had dropped like this to the ground…Courage, heroism, does it really exist? I am about to doubt it, since I haven’t seen anything else than fear, anxiety , and despair in every face during the battle. There was nothing at all like courage, bravery, or the like. In reality, there is nothing else than texting discipline and coercion propelling the soldiers forward» Dominik Richert, 1914.[43]

«Our men have reached an agreement with the French to cease fire. They bring us bread, wine, sardines etc., we bring them schnapps. The masters make war, they have a quarrel, and the workers, the little men…have to stand there fighting against each other. Is that not a great stupidity?…If this were to be decided according to the number of votes, we would have been long home by now» Hermann Baur, 1915.[44]

«I have no idea what we are still fighting for anyway, maybe because the newspapers portray everything about the war in a false light which has nothing to do with the reality…..There could be no greater misery in the enemy country and at home. The people who still support the war haven’t got a clue about anything…If I stay alive, I will make these things public…We all want peace…What is the point of conquering half of the world, when we have to sacrifice all our strength?..You out there, just champion peace! … We give away all our worldly possessions and even our freedom. Our only goal is to be with our wife and children again,» Anonymous Bavarian soldier, 17 October 1914.[45]

See also[edit]

- German entry into World War I

- History of Germany

- History of German foreign policy

- Home front during World War I

- International relations of the Great Powers (1814–1919)

- Central Powers

Notes[edit]

- ^ Jeffrey Verhey, The Spirit of 1914: Militarism, Myth and Mobilization in Germany (Cambridge U.P., 2000).

- ^ N.P. Howard, «The Social and Political Consequences of the Allied Food Blockade of Germany, 1918-19,» German History (1993), 11#2, pp. 161-88 online p. 166, with 271,000 excess deaths in 1918 and 71,000 in 1919.

- ^ Strachan, Hew (1998). World War 1. Oxford University Press. p. 125. ISBN 9780198206149.

- ^ This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Rines, George Edwin, ed. (1920). «Bethmann-Hollweg, Theobald Theodore Friedrich Alfred von» . Encyclopedia Americana.

- ^ Konrad H. Jarausch, «The Illusion of Limited War: Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg’s Calculated Risk, July 1914.» Central European History 2.1 (1969): 48-76.

- ^ Trachtenberg, Marc. «The Meaning of Mobilization in 1914.» International Security 15#3 (1990), pp. 120–50, https://doi.org/10.2307/2538909.

- ^ Fritz Fischer, «1914: Germany Opts for War, ‘Now or Never'», in Holger H. Herwig, ed., The Outbreak of World War I (1997), pp. 70-89 at p. 71.online

- ^ Butler, David Allen (2010). The Burden of Guilt: How Germany Shattered the Last Days of Peace, Summer 1914. Casemate Publishers. p. 103. ISBN 9781935149576. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ^ Barbara Tuchman, The guns of August (1970) p. 84

- ^ Hull, Isabel V. (2005). Absolute Destruction: Military Culture and the Practices of War in Imperial Germany. Cornell University Press. p. 233. ISBN 0801442583. Retrieved 7 July 2009.

- ^ Wolfgang J. Mommsen,»Public opinion and foreign policy in Wilhelmian Germany, 1897–1914.» Central European History 24.4 (1991): 381-401.

- ^ Frauendienst, Werner (1985). «Bethmann Hollweg, Theobald Theodor Friedrich Alfred von». Neue Deutsche Biographie 2 (in German). pp. 188–193 [Online-Version].

- ^ Robert F. Hopwood, «Czernin and the Fall of Bethmann–Hollweg.» Canadian Journal of History 2.2 (1967): 49-61.

- ^ Jeff Lipkes, Rehearsals: The German Army in Belgium, August 1914 (2007)

- ^ Barbara Tuchman, The Guns of August (1962)

- ^ Fred R. Van Hartesveldt, The Battles of the Somme, 1916: Historiography and Annotated Bibliography (1996), pp. 26-27.

- ^ C.R.M.F. Cruttwell, A History of the Great War: 1914-1918 (1935) ch 15-29

- ^ Holger H. Herwig, The First World War: Germany and Austria-Hungary 1914-1918 (1997) ch. 4-6.

- ^ Bruce I. Gudmundsson, Stormtrooper Tactics: Innovation in the German Army, 1914-1918 (1989), pp. 155-70.

- ^ David Stevenson, With Our Backs to the Wall: Victory and Defeat in 1918 (2011), pp. 30-111.

- ^ C.R.M.F. Cruttwell, A History of the Great War: 1914-1918 (1935), pp. 505-35r.

- ^ Millett, Allan (1991). Semper Fidelis: The History of the United States Marine Corps. Simon and Schuster. p. 304. ISBN 9780029215968.

- ^ Tucker, Spencer C. (2005). World War I: A — D. ABC-CLIO. p. 1256. ISBN 9781851094202.

- ^ Roger Chickering, Imperial Germany and the Great War, 1914-1918 (1998) p. 14

- ^ Richie, Faust’s Metropolis, pp. 272-75.

- ^ William H. McNeill, The Rise of the West (1991 edition) p. 742.

- ^ D. G. Williamson, «Walther Rathenau and the K.R.A. August 1914-March 1915,» Zeitschrift für Unternehmensgeschichte (1978), Issue 11, pp. 118-136.

- ^ Hew Strachan, The First World War: Volume I: To Arms (2001), pp. 1014-49 on Rathenau and KRA.

- ^ Feldman, Gerald D. «The Political and Social Foundations of Germany’s Economic Mobilization, 1914-1916,» Armed Forces & Society (1976), 3#1, pp. 121-145. online

- ^ Keith Allen, «Sharing scarcity: Bread rationing and the First World War in Berlin, 1914-1923,» Journal of Social History, (1998), 32#2, pp. 371-93, quote p. 380.

- ^ N. P. Howard, «The Social and Political Consequences of the Allied Food Blockade of Germany, 1918-19,» German History, April 1993, Vol. 11, Issue 2, pp. 161-188.

- ^ a b Cox, Mary Elisabeth (2015-05-01). «Hunger games: or how the Allied blockade in the First World War deprived German children of nutrition, and Allied food aid subsequently saved them». The Economic History Review. 68 (2): 600–631. doi:10.1111/ehr.12070. ISSN 1468-0289. S2CID 142354720.

- ^ Roger Chickering, Imperial Germany and the Great War, 1914-1918 (2004) p. 141-42

- ^ David Welch, Germany, Propaganda and Total War, 1914-1918 (2000) p.122

- ^ Chickering, Imperial Germany, pp. 140-145.

- ^ Keith Allen, «Sharing scarcity: Bread rationing and the First World War in Berlin, 1914-1923,» Journal of Social History (1998) 32#2, 00224529, Winter98, Vol. 32, Issue 2

- ^ Alexandra Richie, Faust’s Metropolis (1998), pp. 277-80.

- ^ A. J. Ryder, The German Revolution of 1918: A Study of German Socialism in War and Revolt (2008)

- ^ Wilhelm Diest and E. J. Feuchtwanger, «The Military Collapse of the German Empire: the Reality Behind the Stab-in-the-Back Myth,» War in History, April 1996, Vol. 3, Issue 2, pp. 186-207.

- ^ Leo Grebler and Wilhelm Winkler, The Cost of the World War to Germany and Austria-Hungary (Yale University Press, 1940)

- ^ N.P. Howard, N.P. «The Social and Political Consequences of the Allied Food Blockade of Germany, 1918-19,» German History (1993) p 162

- ^ Bernd Ulrich said and Benjamin, ed., Ziemann, German Soldiers in the Great War: and Savey Letters and Eyewitness Accounts (Pen and Sword Military, 2010). This book is a compilation of German soldiers’ letters and memoirs. All the references come from this book.

- ^ German Soldiers in the Great War, 77.

- ^ German Soldiers in the Great War, 64.

- ^ German Soldiers in the Great War, 51.

Further reading[edit]

- Watson, Alexander. Ring of Steel: Germany and Austria-Hungary in World War I (2014), excerpt

Military[edit]

- Cecil, Lamar (1996), Wilhelm II: Emperor and Exile, 1900-1941, vol. II, Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press, p. 176, ISBN 978-0-8078-2283-8, OCLC 186744003

- Chickering, Roger, et al. eds. Great War, Total War: Combat and Mobilization on the Western Front, 1914-1918 (Publications of the German Historical Institute) (2000). ISBN 0-521-77352-0. 584 pgs.

- Cowin, Hugh W. German and Austrian Aviation of World War I: A Pictorial Chronicle of the Airmen and Aircraft That Forged German Airpower (2000). Osprey Pub Co. ISBN 1-84176-069-2. 96 pgs.

- Cruttwell, C.R.M.F. A History of the Great War: 1914-1918 (1935) ch 15-29 online free

- Cross, Wilbur (1991), Zeppelins of World War I, Paragon House, ISBN 978-1-55778-382-0

- Herwig, Holger H. The First World War: Germany and Austria-Hungary 1914-1918 (1996), mostly military

- Horne, John, ed. A Companion to World War I (2012)

- Hubatsch, Walther; Backus, Oswald P (1963), Germany and the Central Powers in the World War, 1914–1918, Lawrence, Kansas: University of Kansas, OCLC 250441891

- Karau, Mark D. Germany’s Defeat in the First World War: The Lost Battles and Reckless Gambles That Brought Down the Second Reich (ABC-CLIO, 2015) scholarly analysis. excerpt

- Kitchen, Martin. The Silent Dictatorship: The Politics of the German High Command under Hindenburg and Ludendorff, 1916–1918 (London: Croom Helm, 1976)

- Morrow, John. German Air Power in World War I (U. of Nebraska Press, 1982); Contains design and production figures, as well as economic influences.

- Sheldon, Jack (2005). The German Army on the Somme: 1914 — 1916. Barnsley: Pen and Sword Books Ltd. ISBN 978-1-84415-269-8.

Home front[edit]

- Allen, Keith. «Sharing Scarcity: Bread Rationing and the First World War in Berlin, 1914– 1923,» Journal of Social History (1998), 32#2, pp. 371–96.

- Armeson, Robert. Total Warfare and Compulsory Labor: A Study of the Military-Industrial Complex in Germany during World War I (The Hague: M. Nijhoff, 1964)

- Bailey, S. «The Berlin Strike of 1918,» Central European History (1980), 13#2, pp. 158–74.

- Bell, Archibald. A History of the Blockade of Germany and the Countries Associated with Her in the Great War, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria, and Turkey, 1914–1918 (London: H. M. Stationery Office, 1937)

- Broadberry, Stephen and Mark Harrison, eds. The Economics of World War I (2005) ISBN 0-521-85212-9. Covers France, UK, USA, Russia, Italy, Germany, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and the Netherlands

- Burchardt, Lothar. «The Impact of the War Economy on the Civilian Population of Germany during the First and the Second World Wars,» in The German Military in the Age of Total War, edited by Wilhelm Deist, 40–70. Leamington Spa: Berg, 1985.

- Chickering, Roger. Imperial Germany and the Great War, 1914–1918 (1998), wide-ranging survey

- Daniel, Ute. The War from Within: German Working-Class Women in the First World War (1997)

- Dasey, Robyn. «Women’s Work and the Family: Women Garment Workers in Berlin and Hamburg before the First World War,» in The German Family: Essays on the Social History of the Family in Nineteenth-and Twentieth-Century Germany, edited by Richard J. Evans and W. R. Lee, (London: Croom Helm, 1981), pp. 221–53.

- Davis, Belinda J. Home Fires Burning: Food, Politics, and Everyday Life in World War I Berlin (2000) online edition

- Dobson, Sean. Authority and Upheaval in Leipzig, 1910–1920 (2000).

- Domansky, Elisabeth. «Militarization and Reproduction in World War I Germany,» in Society, Culture, and the State in Germany, 1870–1930, edited by Geoff Eley, (University of Michigan Press, 1996), pp. 427–64.

- Donson, Andrew. «Why did German youth become fascists? Nationalist males born 1900 to 1908 in war and revolution,» Social History, Aug2006, Vol. 31, Issue 3, pp. 337–358

- Feldman, Gerald D. «The Political and Social Foundations of Germany’s Economic Mobilization, 1914-1916,» Armed Forces & Society (1976), 3#1, pp. 121–145. online

- Feldman, Gerald. Army, Industry, and Labor in Germany, 1914–1918 (1966)

- Ferguson, Niall The Pity of War (1999), cultural and economic themes, worldwide

- Hardach, Gerd. The First World War 1914-1918 (1977), economics

- Herwig, Holger H. The First World War: Germany and Austria-Hungary 1914-1918 (1996), one third on the homefront

- Howard, N.P. «The Social and Political Consequences of the Allied Food Blockade of Germany, 1918-19,» German History (1993), 11#2, pp. 161–88 online

- Kocka, Jürgen. Facing total war: German society, 1914-1918 (1984). online at ACLS e-books

- Lee, Joe. «German Administrators and Agriculture during the First World War,» in War and Economic Development, edited by Jay M. Winter. (Cambridge UP, 1922).

- Lutz, Ralph Haswell. The German revolution, 1918-1919 (1938) a brief survey online free

- Marquis, H. G. «Words as Weapons: Propaganda in Britain and Germany during the First World War.» Journal of Contemporary History (1978) 12: 467–98.

- McKibbin, David. War and Revolution in Leipzig, 1914–1918: Socialist Politics and Urban Evolution in a German City (University Press of America, 1998).

- Moeller, Robert G. «Dimensions of Social Conflict in the Great War: A View from the Countryside,» Central European History (1981), 14#2, pp. 142–68.

- Moeller, Robert G. German Peasants and Agrarian Politics, 1914–1924: The Rhineland and Westphalia (1986). online edition

- Offer, Avner. The First World War: An Agrarian Interpretation (1991), on food supply of Britain and Germany

- Osborne, Eric. Britain’s Economic Blockade of Germany, 1914-1919 (2004)

- Richie, Alexandra. Faust’s Metropolis: a History of Berlin (1998), pp. 234–83.

- Ryder, A. J. The German Revolution of 1918 (Cambridge University Press, 1967)

- Siney, Marion. The Allied Blockade of Germany, 1914–1916 (1957)

- Steege, Paul. Black Market, Cold War: Everyday Life in Berlin, 1946-1949 (2008) excerpt and text search

- Terraine, John. «‘An Actual Revolutionary Situation’: In 1917 there was little to sustain German morale at home,» History Today (1978), 28#1, pp. 14–22, online

- Tobin, Elizabeth. «War and the Working Class: The Case of Düsseldorf, 1914–1918,» Central European History (1985), 13#3, pp. 257–98

- Triebel, Armin. «Consumption in Wartime Germany,» in The Upheaval of War: Family, Work, and Welfare in Europe, 1914–1918 edited by Richard Wall and Jay M. Winter, (Cambridge University Press, 1988), pp. 159–96.

- Usborne, Cornelie. «Pregnancy Is a Woman’s Active Service,» in The Upheaval of War: Family, Work, and Welfare in Europe, 1914–1918 edited by Richard Wall and Jay M. Winter, (Cambridge University Press, 1988), pp. 289–416.

- Verhey, Jeffrey. The Spirit of 1914: Militarism, Myth, and Mobilization in Germany (2006) excerpt

- Welch, David. Germany and Propaganda in World War I: Pacifism, Mobilization and Total War (IB Tauris, 2014)

- Winter, Jay, and Jean-Louis Robert, eds. Capital Cities at War: Paris, London, Berlin 1914-1919 (2 vol. 1999, 2007), 30 chapters 1200pp; comprehensive coverage by scholars vol 1 excerpt; vol 2 excerpt and text search

- Winter, Jay. Sites of Memory, Sites of Mourning: The Great War in European Cultural History (1995)

- Ziemann, Benjamin. War Experiences in Rural Germany, 1914-1923 (Berg, 2007) online edition

Primary sources[edit]

- Gooch, P. G. Recent Revelations Of European Diplomacy (1940). pp3–100

- Lutz, Ralph Haswell, ed. Fall of the German Empire, 1914–1918 (2 vol 1932). 868pp online review, primary sources

External links[edit]

- (in German) «Der Erste Weltkrieg» (in English) «The First World War» at Living Museum Online (LeMO)

- Articles relating to Germany at 1914-1918 Online: International Encyclopedia of the First World War

- Hirschfeld, Gerhard: Germany

- Fehlemann, Silke: Bereavement and Mourning (Germany)

- Bruendel, Steffen: Between Acceptance and Refusal — Soldiers’ Attitudes Towards War (Germany)

- Davis, Belinda: Food and Nutrition (Germany)

- Oppelland, Torsten: Governments, Parliaments and Parties (Germany)

- Stibbe, Matthew: Women’s Mobilisation for War (Germany)

- Ungern-Sternberg, Jürgen von: Making Sense of the War (Germany)

- Ullmann, Hans-Peter: Organization of War Economies (Germany)

- Gross, Stephen: War Finance (Germany)

- Altenhöner, Florian: Press/Journalism (Germany)

- Ther, Vanessa: Propaganda at Home (Germany)

- Pöhlmann, Markus: Warfare 1914-1918 (Germany)

- Löffelbein, Nils: War Aims and War Aims Discussions (Germany)

- Whalen, Robert Weldon: War Losses (Germany)

- Germany and the First World War article index at Spartacus Educational

- Posters of the German Military Government in the Generalgouvernement Warshau (German occupied Poland) from World War I, 1915-1916 From the Collections at the Library of Congress

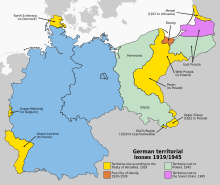

Список глав правительств Германии включает руководителей немецкого национального правительства с 1867 года (включая период послевоенного разделения страны на восточно- и западногерманское государства).

В Северогерманском союзе впервые был установлен пост федерального канцлера. В Германской империи с 1871 по 1918 годы, а также в Веймарской республике с 1919 по 1933 годы и в Третьем рейхе с 1933 по 1945 годы, официальный титул главы правительства был рейхсканцлер. В ФРГ (с 1949 года) он получил название федерального канцлера.

В период ноябрьской революции 1918—1919 годов главой правительства являлся председатель Совета народных уполномоченных, в переходный период при установлении Веймарской республики в 1919 году — премьер-министр.

Также премьер-министр возглавлял правительство ГДР с 1949 по 1958 годы, и в 1990 году перед объединением Германии. С 1958 по 1990 годы он именовался «председатель Совета министров».

Содержание

- 1 Северогерманский союз (1867—1871)

- 2 Германская империя (1871—1918)

- 3 Революционный период (1918—1919)

- 4 Веймарская республика (1919—1933)

- 5 Третий рейх (1933—1945)

- 6 Федеративная Республика Германия (с 1949)

- 6.1 Германская Демократическая Республика (1949—1990)

- 7 Диаграмма пребывания в должности

- 8 Статистика

- 8.1 Наибольший срок пребывания в должности

- 8.2 Наименьший срок пребывания в должности

- 9 См. также

- 10 Примечания

- 11 Ссылки

Северогерманский союз (1867—1871)[править | править код]

Северогерманский союз (нем. Norddeutscher Bund), федеративный союз германских государств, стал этапом реализации объединительных стремлений в Германии. После заключения Пражского мира, увенчавшего победу Пруссии в австро-прусской войне 1866 года, некоторые из государств, отклонивших предложенный им Пруссией перед открытием военных действий нейтралитет (Ганновер, Гессен-Кассель, Нассау, вольный город Франкфурт-на-Майне), были прямо присоединены к ней, равно как и Гольштейн и Шлезвиг. Остальные государства Северной Германии (числом 21) 10 августа 1866 года вошли в состав новой федерации, которая, отвергнув принцип союза государств, организовалась в виде союзного государства, руководящая роль в котором была отведена Пруссии. 18 августа 1866 года был подписан союзный договор, по которому Пруссия и 17 северогерманских государств (осенью присоединились ещё четыре) обязывались принять закон о выборах в межгосударственный парламент, 15 октября прусский ландтаг (нем. Preußischer Landtag) принял закон о выборах в Конституционный рейхстаг Северо-Германского союза (нем. Wahlgesetz für den konstituierenden Reichstag des Norddeutschen Bundes). 12 февраля 1867 года прошли выборы, 24 февраля Конституционный рейхстаг собрался на первое заседание, а 16 апреля принял конституцию Северогерманского союза (нем. Verfassung des Norddeutschen Bundes), по которой 31 августа 1867 года прошли первые выборы в рейхстаг.

Государства, вошедшие в союз, продолжали пользоваться своими конституциями, сохраняли свои сословные собрания в качестве законодательных органов и министерства в качестве исполнительных органов, но должны были уступить союзу военное и морское управление, дипломатические сношения, заведование почтой, телеграфами, железными дорогами, денежной и метрической системами, банками, таможнями.

Кроме рейхстага, был создан союзный совет — бундесрат (нем. Bundesrat), составленный из делегатов отдельных государств, которые были связаны инструкциями своих правительств. Представительство в бундесрате было неравномерным: Пруссия, например, имела 17 голосов, а Саксония — 4. Председателем бундесрата являлся ведавший всеми внешними и внутренними делами союза назначенный королём Пруссии федеральный канцлер (нем. Bundeskanzler). Именно прусскому королю, как федеральному президенту (нем. Bundespräsidium), принадлежало право объявлять войну и заключать мир от имени союза, вести дипломатические переговоры, заключать договоры; в качестве главнокомандующего союзной армией он имел право назначать высших офицеров. Он был главою внутреннего управления, назначал главных должностных лиц союза, созывал и распускал рейхстаг.

| № | Федеральный канцлер | Начало полномочий | Окончание полномочий | Партия | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

граф Отто Эдуард Леопольд фон Бисмарк-Шёнхаузен (1815—1898) нем. Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck-Schönhausen |

1 июля 1867 | 18 января 1871 | независимый |

Германская империя (1871—1918)[править | править код]

Герма́нская импе́рия — принятое в российской историографии название немецкого государства в 1871—1918 годах.

Его официальное название в 1871—1945 годах — Deutsches Reich (Германский рейх) — переводится и как «Германская империя», и как «Германское государство» (с 1943 года — Großdeutsches Reich, «Великогерманское государство / империя»). В историографии этот период времени принято делить на Германскую империю (1871—1918), Веймарскую республику (1918—1933) и Третий рейх (нацистскую Германию) (1933—1945).

После победы в франко-прусской войне 1870 года, по итогам которой к Пруссии были присоединены Эльзас и Лотарингия, 18 января 1871 года в Зеркальной галерее Версальского дворца была провозглашена Германская империя, а титул её кайзера принял Вильгельм I. К империи быстро присоединились государства, не входившие в состав Северогерманского союза — великие герцогства Баден и Гессен, королевства Бавария и Вюртемберг.

На волне популярности Отто фон Бисмарк получил титул князя и был назначен рейхсканцлером (Reichskanzler), став главным органом исполнительной власти и вместе с тем единственным лицом, ответственным перед бундесратом и рейхстагом. В империи не существовало министров, их заменяли подчинённые рейхсканцлеру государственные секретари, председательствовавшие в имперских ведомствах (нем. Reichsämter, первоначально — союзных ведомствах, нем. Bundesamt). Рейхсканцлер назначался и отрешался от должности кайзером.

| № | Рейхсканцлер | Начало полномочий | Окончание полномочий | Партия | Кабинет | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) |

|

князь Отто Эдуард Леопольд фон Бисмарк-Шёнхаузен (1815—1898) нем. Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck-Schönhausen |

21 марта 1871 | 20 марта 1890[1] | независимый | фон Бисмарк (нем.)русск. |

| 2 |

|

генерал от инфантерии, граф[2] Георг Лео фон Каприви де Капрера де Монтекукколи (1831—1899) нем. Georg Leo von Caprivi de Caprera de Montecuccoli |

20 марта 1890 | 28 октября 1894 | фон Каприви (нем.)русск. | |

| 3 |

|

князь Хлодвиг Карл Виктор цу Гогенлоэ-Шиллингсфюрст (1819—1901) нем. Chlodwig Carl Viktor, Fürst zu Hohenlohe-Schillingsfürst |

28 октября 1894 | 17 октября 1900 | Гогенлоэ-Шиллингсфюрст (нем.)русск. | |

| 4 |

|

граф, с 6 сентября 1905 года князь Бернгард Генрих Карл Мартин фон Бюлов (1849—1929) нем. Bernhard Heinrich Martin Karl Graf (Fürst) von Bülow |

17 октября 1900 | 14 июля 1909 | фон Бюлов (нем.)русск. | |

| 5 |

|

Теобальд Теодор Фридрих Альфред фон Бетман-Гольвег (1856—1921) нем. Theobald Theodor Friedrich Alfred von Bethmann Hollweg |

14 июля 1909 | 13 июля 1917 | Бетман-Гольвег (нем.)русск. | |

| 6 |

|

Георг Михаэлис (1857—1936) нем. Georg Michaelis |

13 июля 1917 | 1 ноября 1917 | Михаэлис (нем.)русск. | |

| 7 |

|

граф Георг Фридрих Карл фон Гертлинг (1843—1919) нем. Georg Friedrich Karl Graf von Hertling |

1 ноября 1917 | 3 октября 1918 | Партия Центра | фон Гертлинг (нем.)русск. |

| 8 |

|

Принц Максимилиан Александр Фридрих Вильгельм фон Баден (1867—1929) нем. Maximilian Alexander Friedrich Wilhelm Prinz von Baden |

3 октября 1918 | 9 ноября 1918[1] | независимый | фон Баден (нем.)русск. |

| 9 (а) |

|

Фридрих Эберт (1871—1925) нем. Friedrich Ebert |

9 ноября 1918[3] | 10 ноября 1918[4] | Социал-демократическая партия Германии

в коалиции с Независимой социал-демократической партией Германии |

Революционный период (1918—1919)[править | править код]

Ноя́брьская револю́ция (нем. Novemberrevolution) — революция в ноябре 1918 года в Германской империи, приведшая к установлению в Германии режима парламентской демократии, известного под названием Веймарская республика. Её началом считается восстание матросов в Киле 4 ноября 1918 года, кульминационным моментом — провозглашение республики в полдень 9 ноября, днём формального окончания — 11 августа 1919 года, когда президент республики Фридрих Эберт подписал Веймарскую конституцию.

9 ноября 1918 года рейхсканцлер принц Максимилиан Баденский по собственной инициативе объявил об отречении кайзера от обоих престолов (прусского и имперского) и передал свои полномочия лидеру социал-демократов Фридриху Эберту, который возглавлял большинство в рейхстаге, сформированном по итогам выборов 1912 года. После этого член правительства Максимилиана Баденского Филипп Шейдеман провозгласил Германию республикой. На следующий день Общее собрание берлинских рабочих и солдатских советов (нем. Vollversammlung der Berliner Arbeiter- und Soldatenräte) избрало временные органы государственной власти — Исполнительный совет рабочих и солдатских советов Большого Берлина (нем. Vollzugsrat des Arbeiter- und Soldatenrates Groß-Berlin) и ставший временным правительством Совет народных уполномоченных (нем. Rat der Volksbeauftragten), в состав которого первоначально вошли по 3 представителя социал-демократической и независимой социал-демократической партий.

Первоначально председателями Совета народных уполномоченных (нем. Vorsitzende des Rates der Volksbeauftragten) стали социал-демократ Фридрих Эберт и независимый социал-демократ Гуго Гаазе. Кайзер, находившийся в ставке в Спа, вечером 10 ноября выехал в Нидерланды, где и отрёкся от обоих престолов 28 ноября. 29 декабря 1919 года независимые социал-демократы вышли из Совета народных уполномоченных и он был дополнен социал-демократами.

| № | Председатель[5] Совета народных уполномоченных | Начало полномочий | Окончание полномочий | Партия | Кабинет | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9 (б) |

|

Фридрих Эберт (1871—1925) нем. Friedrich Ebert |

10 ноября 1918[4] | 13 февраля 1919 | Социал-демократическая партия Германии | Совет народных уполномоченных |

| 9 (в) |

|

Гуго Гаазе (1863—1919) нем. Hugo Haase |

29 декабря 1918[1] | Независимая социал-демократическая партия Германии |

Веймарская республика (1919—1933)[править | править код]

После состоявшихся 19 января 1919 года выборов, первое заседание учредительного национального собрания состоялось 6 февраля 1919 года.

10 февраля 1919 года был принят Закон о временной имперской власти, согласно которому главой государства стал рейхспрезидент (нем. Reichspräsident), избираемый национальным собранием, исполнительным органом — имперское министерство (нем. Reichsministerium), назначаемое рейхспрезидентом, состоящее из имперского премьер-министра (нем. Reichsministerpräsident) и имперских министров.

На следующий день (11 февраля) первым рейхспрезидентом был избран Фридрих Эберт. 11 февраля 1919 года он назначил Филиппа Шейдемана первым премьер-министром.

В своём окончательном варианте Веймарская конституция была принята Веймарским учредительным собранием 31 июля 1919 года и подписана рейхспрезидентом Фридрихом Эбертом 11 августа.

По ней в Германии была установлена парламентская демократия с закреплёнными в конституции основными либеральными и социальными правами. На общегосударственном уровне законодательную деятельность в форме имперских законов осуществляли рейхсрат (верхняя палата парламента, орган представительства земель), и выбираемый населением рейхстаг, который также принимал государственный бюджет и смещал с должности рейхсканцлера и любого из министров правительства по схеме вотума недоверия. Рейхсканцлер подчинялся не только рейхстагу, но и рейхспрезиденту, имевшему право назначать его и отправлять в отставку. Рейхспрезидента, часто сопоставляемого с кайзером, избирали на прямых выборах сроком на семь лет. Он мог с согласия рейхсканцлера объявить в стране чрезвычайное положение, на время которого в стране временно прекращали своё действие основные конституционные права. Возможному сопротивлению этому решению со стороны рейхстага противопоставлялось право рейхспрезидента на роспуск парламента. Это сделало возможной фактическую самоликвидацию демократического строя после назначения рейхспрезидентом Гинденбургом на пост рейхсканцлера Адольфа Гитлера в январе 1933 года.

Как правило, в случае отставки кабинета он продолжал действовать в качестве временного правительства до формирования нового кабинета министров (иногда значительный период времени).

| № | Рейхсканцлер (до 14 августа 1919 Премьер-министр) |

Начало полномочий | Окончание полномочий | Партия | Выборы | Кабинет | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 |

|

Филипп Генрих Шейдеман (1865—1939) нем. Philipp Heinrich Scheidemann |

13 февраля 1919 | 27 июня 1919 | Социал-демократическая партия Германии

в коалиции с Немецкой демократической партией и Партией Центра |

1919 (англ.)русск. | Шейдеман (нем.)русск. |

| 11 |

|

Густав Адольф Бауэр (1870—1944) нем. Gustav Adolf Bauer |

27 июня 1919 | 26 марта 1920[1] | Бауэр (нем.)русск. | ||

| 12 (I) |

|

Герман Мюллер (1876—1931) нем. Hermann Müller |

27 марта 1920 | 8 июня 1920 | Мюллер—I (нем.)русск. | ||

| 13 |

|

Константин Ференбах (1852—1926) нем. Constantin Fehrenbach |

8 июня 1920 | 4 мая 1921[6] | Партия Центра

в коалиции с Немецкой народной партией и Немецкой демократической партией |

1920 (англ.)русск. | Ференбах (нем.)русск. |

| 14 (I—II) |

|

Карл Йозеф Вирт (1879—1956) нем. Karl Josef Wirth |

10 мая 1921 | 21 октября 1921[6] | Партия Центра

в коалиции с Социал-демократической партией Германии и Немецкой демократической партией |

Вирт—I (нем.)русск. | |

| 26 октября 1921 | 14 ноября 1922[6] | Вирт—II (нем.)русск. | |||||

| 15 |

|

Вильгельм Карл Йозеф Куно (1876—1933) нем. Wilhelm Carl Josef Cuno |

22 ноября 1922 | 14 августа 1923[6] | независимый

в коалиции с Партией Центра, |

Куно (нем.)русск. | |

| 16 (I—II) |

|

Густав Эрнст Штреземан (1878—1929) нем. Gustav Ernst Stresemann |

14 августа 1923 | 3 октября 1923[6] | Немецкая народная партия

в коалиции с Немецкой демократической партией и Социал-демократической партией Германии[7] |

Штреземан—I (нем.)русск. | |

| 6 октября 1923 | 23 ноября 1923[6] | Штреземан—II (нем.)русск. | |||||

| 17 (I—II) |

|

Вильгельм Маркс (1863—1946) нем. Wilhelm Marx |

30 ноября 1923 | 26 марта 1924[6] | Партия Центра

в коалиции с Немецкой народной партией, Немецкой демократической партией и Баварской народной партией |

Маркс—I (нем.)русск. | |

| 3 июня 1924 | 15 декабря 1924[6] | Партия Центра

в коалиции с Немецкой народной партией и Немецкой демократической партией |

1924, май (англ.)русск. | Маркс—II (нем.)русск. | |||

| 18 (I—II) |

|

Ганс Лютер (1879—1962) нем. Hans Luther |

15 января 1925 | 5 декабря 1925[6] | независимый

в коалиции с Партией Центра, Немецкой народной партией, Немецкой демократической партией, Баварской народной партией и Немецкой национальной народной партией[8] |

1924, декабрь (англ.)русск. | Лютер—I (нем.)русск. |

| 20 января 1926 | 12 мая 1926[6] | независимый

в коалиции с Партией Центра, |

Лютер—II (нем.)русск. | ||||

| 17 (III—IV) |

|

Вильгельм Маркс (1863—1946) нем. Wilhelm Marx |

17 мая 1926 | 1 февраля 1927[9] | Партия Центра

в коалиции с Немецкой народной партией, Немецкой национальной народной партией и Баварской народной партией |

Маркс—III (нем.)русск. | |

| 1 февраля 1927 | 12 июня 1928[6] | Партия Центра

в коалиции с Немецкой народной партией и Немецкой демократической партией |

Маркс—IV (нем.)русск. | ||||

| 12 (II) |

|

Герман Мюллер (1876—1931) нем. Hermann Müller |

28 июня 1928 | 27 марта 1930[6] | Социал-демократическая партия Германии

в коалиции с Партией Центра, Немецкой демократической партией, Немецкой народной партией и Баварской народной партией |

1928 | Мюллер—II (нем.)русск. |

| 19 (I—II) |

|

Генрих Алойзиус Мария Элизабет Брюнинг (1885—1970) нем. Heinrich Aloysius Maria Elisabeth Brüning |

29 марта 1930 | 10 октября 1931 | Партия Центра

в коалиции с Немецкой народной партией, Немецкой демократической партией, Баварской народной партией, Партией немецкого среднего класса (англ.)русск. и Консервативной народной партией (англ.)русск. |

Брюнинг—I (нем.)русск. | |

| 1930 | |||||||

| 10 октября 1931 | 30 мая 1932[6] | Партия Центра

в коалиции с Баварской народной партией, Немецкой государственной партией и Консервативной народной партией (англ.)русск. |

Брюнинг—II (нем.)русск. | ||||

| 20 |

|

Франц Йозеф Герман Михаэль Мария фон Папен (1879—1969) нем. Franz Joseph Hermann Michael Maria von Papen |

1 июня 1932 | 17 ноября 1932[6] | независимый[10]

в коалиции с Немецкой национальной народной партией |

1932, июль | фон Папен (нем.)русск. |

| 21 |

|

генерал от инфантерии Курт Фердинанд Фридрих Герман фон Шлейхер (1882—1934) нем. Kurt Ferdinand Friedrich Hermann von Schleicher |

3 декабря 1932 | 28 января 1933[11] | независимый

в коалиции с Немецкой национальной народной партией |

1932, ноябрь | фон Шлейхер (нем.)русск. |

Третий рейх (1933—1945)[править | править код]

Тре́тий рейх (нем. Drittes Reich — Третья империя, Третья держава) — неофициальное название Германии с 24 марта 1933 года (когда был принят закон «О защите народа и рейха», предоставивший Адольфу Гитлеру чрезвычайные полномочия и основу для создания диктатуры) по 23 мая 1945 года. Первая дата является условной, в части источников в качестве даты основания Третьего рейха используется 30 января 1933 года (назначение Гитлера рейхсканцлером).

Официальное название Германии с 1871 года по 26 июня 1943 года — Deutsches Reich, с 26 июня 1943 по 23 мая 1945 года — Großdeutsches Reich (Великогерманская империя). Слово «рейх», обозначающее земли, подчинённые одной власти, обычно переводится как «государство» или «империя» в зависимости от контекста.

В этот период страна представляла собой тоталитарное государство с однопартийной системой и доминирующей идеологией (национал-социализмом), контролю подвергались все сферы жизни общества. Третий рейх связан с властью Национал-социалистической немецкой рабочей партии под руководством Адольфа Гитлера, который после смерти рейхспрезидента Гинденбурга (2 августа 1934 года) стал главой государства (официальный титул — «фюрер и рейхсканцлер»).

Федеративное устройство Германии, установленное Веймарской конституцией, было заменено унитарным построением государства законом «О новом устройстве рейха» (Gesetz über den Neuaufbau des Reichs) от 30 января 1934 года.

После военного поражения во Второй мировой войне Гитлер покончил с собой 30 апреля 1945 года, передав в своём политическом завещании власть назначенным рейхспрезидентом гроссадмиралу Карлу Дёницу и рейхсканцлером Йозефу Геббельсу. Узнав 1 мая о самоубийстве Геббельса, Дёниц договорился о формировании правительства с графом Людвигом Шверином фон Крозигом, отказавшимся от поста рейхсминистра и ставшим главным министром кабинета.

23 мая 1945 года Фленсбургское правительство (названное так по месту своего фактического пребывания в городе Фленсбург недалеко от границы с Данией и пытавшееся управлять ещё не оккупированной союзниками территорией) было арестовано в соответствии с приказом Верховного главнокомандующего экспедиционными силами союзников генерала армии Эйзенхауэра.

| № | Фюрер и рейхсканцлер (до 2 августа 1934 рейхсканцлер, с 1 мая 1945 главный министр) |

Начало полномочий | Окончание полномочий | Партия | Выборы | Кабинет | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 22 |

|

Адольф Гитлер (1889—1945) нем. Adolf Hitler |

30 января 1933 | 30 апреля 1945[12] | Национал-социалистическая немецкая рабочая партия

до 27 июня 1933 года в коалиции с Немецкой национальной народной партией[13] |

1933, март | Гитлер |

| 1933, ноябрь | |||||||

| 1936 | |||||||

| 1938 | |||||||

| 23 |

|

Пауль Йозеф Геббельс (1897—1945) нем. Paul Joseph Goebbels |

30 апреля 1945[14] | 1 мая 1945[12] | Национал-социалистическая немецкая рабочая партия | Геббельс | |

| 24 |

|

граф Иоганн Людвиг Шверин фон Крозиг (1887—1977) нем. Johann Ludwig Graf Schwerin von Krosigk |

1 мая 1945 | 23 мая 1945[15] | независимый

в коалиции с Национал-социалистической немецкой рабочей партией |

фон Крозиг |

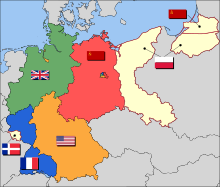

Федеративная Республика Германия (с 1949)[править | править код]

Федерати́вная Респу́блика Герма́ния[16] (нем. Bundesrepublik Deutschland) была провозглашена 23 мая 1949 года на территориях, расположенных на американской, британской и французской зонах оккупации нацистской Германии (Тризония). Предполагалось, что впоследствии в её состав войдут и остальные германские территории, что предусматривалось и обеспечивалось специальной статьёй 23 Конституции ФРГ. В том же году 7 октября на территории советской зоны оккупации была провозглашена Германская Демократическая Республика, территория которой 3 октября 1990 года после мирной революции в ГДР была интегрирована в состав ФРГ.

Федеральный президент (глава государства) выполняет представительские функции и назначает федерального канцлера, который является главой Федерального правительства и руководит его деятельностью.

| № | Федеральный канцлер | Начало полномочий | Окончание полномочий | Партия | Выборы | Кабинет | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 (I—V) |

|

Конрад Герман Йозеф Аденауэр (1876—1967) нем. Konrad Hermann Joseph Adenauer |

15 сентября 1949 | 20 октября 1953 | Христианско-демократический союз Германии / Христианско-социальный союз в Баварии[17] в коалиции с Немецкой партией и Свободной демократической партией |

1949 | Аденауэр—I (нем.)русск. |

| 20 октября 1953 | 29 октября 1957 | Христианско-демократический союз Германии / Христианско-социальный союз в Баварии[17] в коалиции с Немецкой партией, Свободной демократической партией (до 23 февраля 1956 года)[18] и Всегерманским блоком / Лигой эмигрантов и лишённых прав (англ.)русск. |

1953 | Аденауэр—II (нем.)русск. | |||

| 29 октября 1957 | 14 ноября 1961 | Христианско-демократический союз Германии / Христианско-социальный союз в Баварии[17] в коалиции с Немецкой партией |

1957 | Аденауэр—III (нем.)русск. | |||

| 14 ноября 1961 | 13 декабря 1962 | Христианско-демократический союз Германии / Христианско-социальный союз в Баварии[17] в коалиции со Свободной демократической партией |

1961 | Аденауэр—IV (нем.)русск. | |||

| 14 декабря 1962 | 11 октября 1963 | Аденауэр—V (нем.)русск. | |||||

| 26 (I—II) |

|

Людвиг Вильгельм Эрхард (1897—1977) нем. Ludwig Wilhelm Erhard |

17 октября 1963 | 26 октября 1965 | Христианско-демократический союз Германии / Христианско-социальный союз в Баварии[17] до 28 октября 1966 года в коалиции со Свободной демократической партией[19] |

Эрхард—I (нем.)русск. | |

| 26 октября 1965 | 30 ноября 1966 | 1965 | Эрхард—II (нем.)русск. | ||||

| 27 |

|

Курт Георг Кизингер (1904—1988) нем. Kurt Georg Kiesinger |

1 декабря 1966 | 21 октября 1969 | Христианско-демократический союз Германии / Христианско-социальный союз в Баварии[17] в коалиции с Социал-демократической партией Германии |

Кизингер (нем.)русск. | |

| 28 (I—II) |

|

Вилли Брандт (1913—1992) нем. Willy Brandt (настоящее имя — Герберт Эрнст Карл Фрам нем. Herbert Ernst Karl Frahm) |

22 октября 1969 | 15 декабря 1972 | Социал-демократическая партия Германии

в коалиции со Свободной демократической партией |

1969 | Брандт—I (нем.)русск. |

| 15 декабря 1972 | 7 мая 1974 | 1972 | Брандт—II (нем.)русск. | ||||

| и.о. |

|

Вальтер Шеель (1919—2016) нем. Walter Scheel |

7 мая 1974 | 16 мая 1974 | Свободная демократическая партия

в коалиции с Социал-демократической партией Германии |

||

| 29 (I—III) |

|

Гельмут Генрих Вальдемар Шмидт (1918—2015) нем. Helmut Heinrich Waldemar Schmidt |

16 мая 1974 | 14 декабря 1976 | Социал-демократическая партия Германии

до 17 сентября 1982 года в коалиции со Свободной демократической партией[20] |

Шмидт—I (нем.)русск. | |

| 16 декабря 1976 | 4 ноября 1980 | 1976 | Шмидт—II (нем.)русск. | ||||

| 6 ноября 1980 | 1 октября 1982 | 1980 | Шмидт—III (нем.)русск. | ||||

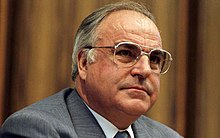

| 30 (I—V) |

|

Гельмут Йозеф Михаэль Коль (1930—2017) нем. Helmut Josef Michael Kohl |

1 октября 1982 | 29 марта 1983 | Христианско-демократический союз Германии / Христианско-социальный союз в Баварии[17] в коалиции со Свободной демократической партией |

Коль—I (нем.)русск. | |

| 30 марта 1983 | 11 марта 1987 | 1983 | Коль—II (нем.)русск. | ||||

| 12 марта 1987 | 18 января 1991 | Христианско-демократический союз Германии / Христианско-социальный союз в Баварии[17] в коалиции со Свободной демократической партией |

1987 | Коль—III (нем.)русск. | |||

| 18 января 1991 | 17 ноября 1994 | Христианско-демократический союз Германии / Христианско-социальный союз в Баварии[17] в коалиции со Свободной демократической партией |

1990 | Коль—IV (нем.)русск. | |||

| 17 ноября 1994 | 27 октября 1998 | 1994 | Коль—V (нем.)русск. | ||||

| 31 (I—II) |

|

Герхард Фриц Курт Шрёдер (1944—) нем. Gerhard Fritz Kurt Schröder |

27 октября 1998 | 22 октября 2002 | Социал-демократическая партия Германии

в коалиции с Союзом 90/Зелёные |

1998 | Шрёдер—I (нем.)русск. |

| 22 октября 2002 | 22 ноября 2005 | 2002 | Шрёдер—II (нем.)русск. | ||||

| 32 (I—IV) |

|

Ангела Доротея Меркель (1954—) нем. Angela Dorothea Merkel |

22 ноября 2005 | 28 октября 2009 | Христианско-демократический союз Германии / Христианско-социальный союз в Баварии[17] в коалиции с Социал-демократической партией Германии |

2005 | Меркель—I |

| 28 октября 2009 | 17 декабря 2013 | Христианско-демократический союз Германии / Христианско-социальный союз в Баварии[17] в коалиции со Свободной демократической партией |

2009 | Меркель—II | |||

| 17 декабря 2013 | 14 марта 2018 | Христианско-демократический союз Германии / Христианско-социальный союз в Баварии[17] в коалиции с Социал-демократической партией Германии |

2013 | Меркель—III | |||

| 14 марта 2018 | действующий | 2017 | Меркель—IV |

Германская Демократическая Республика (1949—1990)[править | править код]

Герма́нская Демократи́ческая Респу́блика (ГДР) (нем. Deutsche Demokratische Republik, DDR) — государство, существовавшее с 7 октября 1949 года до 3 октября 1990 года.

Основной закон Федеративной Республики Германии, принятый 23 мая 1949 года, германские земли Советской оккупационной зоны не признал. 15—16 мая 1949 года в них прошли выборы делегатов Немецкого народного конгресса, который 30 мая 1949 года принял конституцию ГДР, признанную пятью землями Советской зоны оккупации и оформившую их политический союз.

В ходе II-го Немецкого народного конгресса 19 марта 1948 года был выделен постоянно действующий Народный совет. 7 октября 1949 года Народный совет провозгласил создание ГДР и сам реорганизовался в Народную палату ГДР.

Выборы в Народную палату и Палату земель первого созыва были назначены на 19 октября 1949 года, до их проведения и формирования Правительства были образованы Временные законодательные органы и Временное правительство, президентом и премьер-министром были избраны сопредседатели Социалистической единой партии Германии (СЕПГ) Вильгельм Пик и Отто Гротеволь, заместителями премьер-министра — заместитель председателя СЕПГ Вальтер Ульбрихт, председатель Либерально-демократической партии Германии (ЛДПГ) Герман Кастнер и председатель Христианско-демократического союза (ХДС) Отто Нушке (англ.)русск.. 30 февраля 1950 года СЕПГ, ЛДПГ и ХДС создали Национальный фронт демократической Германии (нем. Nationale Front des Demokratischen Deutschlands, с 1973 года — Национальный фронт ГДР, нем. Nationale Front der DDR), сформировавший единый и фактически единственный избирательный список, который победил на выборах в Палату земель и Народную палату. 8 ноября 1950 года Народной палатой было сформировано постоянное Правительство во главе с Отто Гротеволем, состоявшее только из представителей Национального фронта. В последующем формирование правительства Народным фронтом во главе с представителем СЕПГ стало традиционным.

23 февраля 1952 года земли были упразднены, соответственно были упразднены их законодательные органы (ландтаги) и земельные правительства, отменены земельные конституции и земельные законы.

До 8 декабря 1958 года должность главы правительства называлась премьер-министр (нем. Ministerpräsident der Deutschen Demokratischen Republik), затем — председатель Совета министров (нем. Vorsitzende des Ministerrates der Deutschen Demokratischen Republik), с 1990 года вновь премьер-министр.

5 декабря 1989 года Национальный фронт покинули ХДС и ЛДПГ, в связи с чем фронт потерял своё значение. 16 декабря правящая СЕПГ была преобразована в Партию демократического социализма и дистанцировалась от прежней политики. 20 февраля 1990 года поправка к конституции ГДР исключила из неё упоминания Национального фронта.[22]

3 октября 1990 года произошло вхождение ГДР и Западного Берлина в состав ФРГ в соответствии с конституцией ФРГ. На территории ГДР были воссозданы пять новых земель, объединённый Берлин также был провозглашён самостоятельной землёй. Правовую основу для объединения положил Договор об окончательном урегулировании в отношении Германии.

| № | Председатель Совета министров (до 8 декабря 1958 года и с 12 апреля 1990 года премьер-министр) |

Начало полномочий | Окончание полномочий | Партия | Выборы | Кабинет | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| А (I—V) |

|

Отто Гротеволь (1894—1964) нем. Otto Grotewohl |

7 октября 1949 | 8 ноября 1950 | Социалистическая единая партия Германии

в коалиции с Либерально-демократической партией Германии и Христианско-демократическим союзом |

1949 (англ.)русск. | Гротеволь—I (нем.)русск. |

| 8 ноября 1950 | 19 ноября 1954 | Социалистическая единая партия Германии

во главе Национального фронта демократической Германии |

1950 (англ.)русск. | Гротеволь—II (нем.)русск. | |||

| 19 ноября 1954 | 7 декабря 1958 | 1954 (англ.)русск. | Гротеволь—III (нем.)русск. | ||||

| 7 декабря 1958 | 14 ноября 1963 | 1958 (англ.)русск. | Гротеволь—IV (нем.)русск. | ||||

| 14 ноября 1963 | 21 сентября 1964[23] | 1963 (англ.)русск. | Гротеволь—V / Штоф—I (нем.)русск. | ||||

| Б (I—III) |

|

Вилли Штоф (1914—1999) нем. Willi Stoph |

24 сентября 1964[24] | 14 июля 1967 | |||

| 14 июля 1967 | 26 ноября 1971 | 1967 (англ.)русск. | Штоф—II (нем.)русск. | ||||

| 26 ноября 1971 | 3 октября 1973 | 1971 (англ.)русск. | Штоф—III / Зиндерман (нем.)русск. | ||||

| В |

|

Хорст Зиндерман (1915—1990) нем. Horst Sindermann |

3 октября 1973 | 29 октября 1976 | Социалистическая единая партия Германии

во главе Национального фронта ГДР |

||

| Б (IV—VI) |

|

Вилли Штоф (1914—1999) нем. Willi Stoph |

29 октября 1976 | 26 июня 1981 | 1976 (англ.)русск. | Штоф—IV (нем.)русск. | |

| 26 июня 1981 | 17 июня 1986 | 1981 (англ.)русск. | Штоф—V (нем.)русск. | ||||

| 17 июня 1986 | 13 ноября 1989 | 1986 | Штоф—VI (нем.)русск. | ||||

| Г |

|

Ханс Модров (1928—) нем. Hans Modrow |