Оглавление

- 0.Часть Нулевая.

Предисловие - 1.Часть Первая.

А где его взять, этот Бейсик? - 2. Часть Вторая.

Как запустить этот Бейсик? - 3. Часть Третья.

Интерфейс или куда тыкать - 4. Часть Четвертая.

Начинаем программировать - 5. Часть Пятая.

Переменные — или САМОЕ ВАЖНОЕ - 6. Часть Шестая.

Все об операторе

PRINT и математика в Бейсике - 7. Часть Седьмая.

Первая игра - 8. Часть Восьмая.

Сохранение, Загрузка, Компилирование - 9. Часть Девятая.

Немного об экранных режимах - 10. Часть Десятая.

Циклы. FOR и NEXT - 11. Часть Одиннадцатая. Введение в

Графику — Кружочки, точки и прочая хрень - 12. Часть Двенадцатая. DRAW — красиво

и быстро - 14. Часть Четырнадцатая. Эффект движения

- 15. Часть Пятнадцатая.

Опрос клавиатуры - 16. Часть Шестнадцатая.

Генератор случайных чисел - 17. Часть Семнадцатая. Вторая

игра. - 18. Часть Восемнадцатая. Музыка и Звуки.

- 19. Часть Девятнадцатая. Продвинутая

графика: GET и PUT - 20. Часть Двадцатая.

Проблемы и Дополнения.

0. Часть

Нулевая. Предисловие

День Добрый. Данная писанина предназначена для тех, кто

хочет начать заниматься программированием, но не знает на чем и не

знает как. Поэтому я постараюсь все объяснять доступно, по

рабоче-крестьянски. И, в отличие от всяких там книжек, если у вас в

голове возникли каке-либо мысли вроде: «Ни чего не понял, чего этот тип

написал» вы можете без проблем написать мне о своей проблеме на мыло: m_rechkov@yourline.ru, или,

как вариант, набрать в поле ввода адреса своего браузера (или броузера) http://quitbasic.narod.ru (если

кто не знает — один из лучших сайтов в Рунете по QBasic’у) и зайти на

форум. Там я или оные лица попробуют ответить и помочь (но не деньгами).

Итак, здесь будут объясняться ОСНОВЫ и некоторые ПРОСТЫЕ РЕШЕНИЯ

сложных проблем без вникания в их суть. После изучения энного

количества килобайт текста вы сможете более-менее ориентироваться в

QBasic’e. Если этого не случится, значит либо я плохо поработал (чего не

может быть! Однозначно!), либо ваш отец Папа Карло. Начнем…

1. Часть Первая —

А где его взять, этот Бейсик?

Здесь и далее будет идти речь о QuickBasic’e 4.5 А где ж его взять-то?

Вариант первый — зайти на вышеупомянутый сайт, кликнуть на [Архив] ->

[Компиляторы] и скачать себе нужную версию. Весит она около мегабайта.

Вариант второй — берите где хотите.

2. Часть Вторая —

Как запустить этот Бейсик?

Ну, допустим, скачали вы себе архив, разархивировали куда-нибудь

в c:\qb. «А че дальше-то?» — хотите вы сказать. А мы заходим в папку с

Бейсиком и запускаем файл QB.EXE. Видим примерно такой пейзаж:

На этой картинке я накалякал немного пояснений. Большинство из пунктов

меню нам нахрен не нужно, а вот некоторые из пунктов мы сейчас рассмотрим

3. Часть Третья —

Интерфейс или че-куда тыкать

Начнем с меню File (для того чтобы открыть это меню нужно щелкнуть на

нем мышкой или, по-пацански, нажать ALT а потом на F). В нем есть пункты

New Program — создать новую программу; Open Program… — открыть

программу; Save и Save As… — сохранить и сохранить как, и Exit —

остальные нам не понадобятся. В меню Edit: Undo — отменить

последний ввод; Cut — вырезать в буфер; Copy — копировать туда же;

Paste — вставить оттуда; Clear — удалить все нахрен. А теперь слушайте

внимательно: посмотрите на клавиатурные комбинации рядом с командами —

быстро выучите их и не вздумайте лазить в это меню для редактирования!

Все делайте только с клавиатуры! Этим вы продлите себе жизнь лет на

10-15. Меню Search: Find — найти какие-нибудь символы, а Change —

найти что-нибудь, а потом заменить (иногда довольно полезная

вещь). Run: Start- запуск написанного вами кода с начала;

Continue — продолжение выполнения программы после прерывания ее.

Make EXE File… — позволяет сделать из *.bas файла настоящую

EXE-версию вашего кода, чтобы ее можно было запускать на машине без

Бейсика. Подробнее мы рассмотрим ее позднее. Ну и хватит — остальное

посмотрите сами, если понадобится. Внимание! Запомните это: чтобы

переключиться на рус. язык надо зажать правый контрл и правый альт, а

чтобы на англ. язык, то на те же клавиши, только слева. И еще — если вы

запустили программу, а выхода из нее не предусмотрели, то зажмите

Ctrl+Break и все будет хорошо. И еще, чтобы при наборе кода

перейти на новую строку нажмите на [ENTER]. А теперь постарайтесь

выучить самое важное, покурите (но не шмаль! Шмаль будете курить, когда

дело дойдет до программирования. Иногда, чтобы найти решение, бывает

нужно погрузиться в Нирвану)

4. Часть Четвертая

— Начинаем программировать

Тушим папиросу, запускаем Бейсик и вводим

следующий код

CLS

PRINT «Hello World!»

END

И запускаем полученную программу («А как это

сделать?» — скажете вы. Или не скажите? А если скажите, то — ЧИТАЙТЕ

Часть №3) SHIFT+F5

И чего мы видим? А видим мы на пустом и черном фоне

надпись белыми буквами : Hello World! Ага, а теперь можете налить себе

стакан красного — вы написали свою первую прогу! Только вы сами ни хрена

не поняли, чего написали. Так? Но сейчас мы все разберем. Вверху у нас

стоит команда CLS. Это команда

очистки экрана, т.е. после этой команды экран напрочь очищается и

предстает перед нами в девственном виде. А дальше идет оператор PRINT. Он позволяет выводить

символы на экран. В нашем случае мы выводим ТЕКСТ, поэтому текст мы

заключаем в кавычки, а если бы мы захотели вывести на экран число, то

кавычки бы мы не ставили, а писали просто PRINT 999 или PRINT 7.5 (заметьте, в Бейсике

дробную часть отделяет точка, а не запятая). Попробуете теперь вывести

на экран надписи: Rock — лучшая музыка в мире! и Аквариум, Калинов

Мост, The Doors, а также числа: 75, 0.55, 1234567890.

Получается? Хорошо. А сейчас попробуйте убрать CLS и несколько раз подряд

запустить программу — вы наглядно убедитесь для чего это самое CLS

нужно. А теперь сделайте так, чтобы под надписью Hello World! шла цифра

777. Надеюсь, ума у вас хватит…

5. Часть Пятая.

Переменные — или САМОЕ ВАЖНОЕ

Теперь о самом важном. Вам необходимо уяснить понятия о

переменных и операторе присваивания. Итак, переменная, это — область

данных, имеющая имя. По простому, мы можем присваивать разное значение

одинаковым именам. Исполните эту программу:

CLS

a=100

text$=»РОК»

PRINT a

PRINT text$

END

Ага, что у нас получилось. Получилось то, что на

экране вывелось число 100, а под ним надпись РОК. Почему так получилось?

Разберем все по проядку. Что означает строка a=100. Она означает то, что

переменной под именем [a] присвоили значение [100], а знак [=] и есть

оператор присваивания, т.е. он присваивает переменной определенное

значение. Строка text$=»РОК» означает то же самое,

что и предыдущая,только тут не число, а текст и на конце переменной

стоит символ $, и значение переменной будет текстовое, а раз текстовое,

то мы его заключаем в кавычки. Такая переменная называется строковой. А

после команд PRINT мы просто

подставляем имя нужной нам переменной и эта самая переменная выводится

на экран. Теперь о том, какие имена могут быть у переменных. Запомним,

имена должны состоять только из латинских букв и они не должны

начинаться с цифры, большие и маленькие буквы Бейсиком не различаются.

Т.е. возможны такие имена файлов: a, abc$, nom1, LaLa, а нельзя вводить

так: Ш, 1a, abГ. Переменную можно приравнять к другой

переменной. К примеру, введем такой код:

N1=200

N2=N1

PRINT N2

Все, с этим разобрались. Вся эта часть очень важна. Если не

поняли ее содержания, то купите себе веревку, мыло и табуретку…

6. Часть Шестая.

Все об операторе PRINT и математика в Бейсике

Переменной можно присвоить не только какое-либо

значение, но также и математическую формулу, например a=100*2-10, или b=(a+150)*2.75 А теперь о

том ,как в Бейсике записывать эти самые формулы правильно. Ну,

во-первых, как и в математике сначала выполняются действия в скобках,

потом умножения и т.д. Знак умножения выглядит так: [*], деления: [/],

ну [+] и [-] это понятно, степени: ^ n(зажми шестерку при нажатом

шифте), где n — сама степень, SQR(n) — квадратный корень (т.е.

вместо n в скобки подставляем нужное), SIN(n)- это синус, такого же вида

и COS, TAN и т.д. INT(n) — что-то вроде округления. Остальные

математические штуки можно всегда посмотреть во встроенное справке

Бейсика. И еще, запомните одну вещь: нельзя, как в математике, писать

слитно цифру и переменную, т.е. забудте про 2a, писать надо 2*a. Все, с

математикой покончено.

Теперь разберемся с PRINT’oм. В передыдущих примерах

мы писали подряд два оператора PRINT и притом

, что должен был вывести второй оператор он выводил на другой строке. А

что делать, если надо на той же? Смотрим:

CLS

a=5^2

PRINT «5 во второй степени будет

равно «;a; » и это правда»

Посмотрим, что у нас получилось. В одну строку все вместилось,

правда ведь? Разберем все последовательно: сначала идет текст, послне

него идет [;], после этой точки с запятой можно писать еще что-нибудь в

том же операторе и это что-нибудь будет выводится на той же строке; а у

нас здесь стоит переменная a, которой мы присвоили нужное нам значение,

после переменной опять [;] и завершающая фраза. Вместо [;] можно

поставить [,], тогда текст будет выводится через определенное кол-во

символов. Это бывает полезно для создания вякого рода таблиц. Еще одно

примечание: в PRINT можно подставлять не

переменные а сразу формулы, например можно записать и так: PRINT «5 во второй степени

будет равно «;5^2; » и это правда».

7. Часть Седьмая. Первая игра

Готовтесь, дети мои. Сейчас мы создадим первое подобие игры. Пишем код:

CLS

PRINT «Игра: Крутой Математик»

PRINT «Решите пример: (500-100)*2»

Nach:

INPUT a

IF colO = 5 THEN PRINT «Тебе ничто

уже не поможет»: END

IF a = (500 — 100) * 2 THEN PRINT «Ты

умный тип, однако!»: END

IF a <> (500 — 100) * 2 THEN

PRINT «Учи математику, идиот. Попробуй снова:»: colO = colO + 1: GOTO

Nach

Итак, запустите эту писанину и посмотрите, что она

делает. А она делает вот что: сначала выводится название игры и задание

— вычислить то-то то-то. А затем идет знак вопроса, после которого вы

вводите нужное число и жмете на [ENTER]. Если число равно (500-100)*2,

т.е. 800, то выводится надпись [Ты умный тип, однако!] и прогамма

завершает работу, а если ответ неправильный, то пишется [Учи математику,

идиот. Попробуй снова:] и все повторяется заново, но если вы настолько

умалишенны, что за пять попыток не подсчитаете нужное число, то

программа выводит [Тебе ничто уже не поможет] и завершает свою

работу.

Сейчас разберем новые команды. Ну, сначала определим,

что означает знак [:], а он просто-напросто позваляет выполнить другую

команду в той же строке, для экономии, так сказать, экранного места.

Оператор INPUT позволяет вам вводить нужные данные с клавиатуры. В нашем

случае с помощью него мы вводим значение числовой переменной a. То что

мы введем, то и будет новым значением переменной. А теперь о операторе

IF THEN, дословно он означает [ЕСЛИ] … [ТО] … Т.е. в строке IF a = (500 — 100) * 2 THEN PRINT «Ты

умный тип, однако!»: END происходит следующее: ЕСЛИ a=столько-то,

TO пишем такой-то текст и завершаем программу. Понятно, да? А теперь о

том, что мы делаем, для того чтобы после пяти неправильных попыток

программа писала о вас, то что она думает. За счетчик попыток мы взяли

переменную colO, по умолчанию все переменные равны нулю. Теперь разберем

строку IF a <> (500 — 100) * 2

THEN PRINT «Учи математику, идиот. Попробуй снова:»: colO = colO + 1:

GOTO Nach Получается: ЕСЛИ a не равно (знак <> означает

не равно) нужному числу ТО пишем текст и добавляем к переменной colO

единицу, т.е. она будет равна своему предыдущему значению плюс единица

(очень важно это понять!). И когда у нас эта переменная будет равна

пяти, то мы с помощью стоки IF colO

= 5 THEN PRINT «Тебе ничто уже не поможет»: END напишем нужное

нам и завершим программу. А как нам сделать так, чтобы программа

возвращалась к вводу переменной a, если ответ неправилен. Смотрим на

предыдущую строку и видим: GOTO Nach.

Оператор GOTO — это безусловный переход. Т.е. при обращении к этому

оператору программа переходит к указанной в операторе метке, в нашем

случае метка носит название Nach.

Теперь посмотрите на 4-ю строчку кода: Nach: После метки в программе

всегда ставится двоеточие, чтобы Бейсик понял, что это метка.

Следовательно, после нашей команды GOTO программа переходит к

этой метке и снова начинает выполнять строку INPUT a. Теперь вам все должно

быть понятно. Главное во всем разобраться. Попробуйте видоизменить

программу, добавить в нее что-нибудь. Изменить формулу. Добавить

всякие надписи или усложнить условие. Главное, чтобы у вас было 15-20

грамм мозгов и до хрена терпения. А, кстати, попробуйте убрать строку

где написано «Решите..», а строку с инпутом измените так: INPUT «Решите пример: (500-100)*2»; a. Так будет лучше…

8. Часть Восьмая.

Сохранение, Загрузка, Компилирование

Что же делать, если вы хотите сохранить ваше первое жалкое подобие

игры? Воспользуемся меню File -> Save. Нам откроется следующее

окно:

Рассмотрите надписи на рисунке и вы все поймете. Немного про имена

файла: В DOS’e, под которым Бейсик и работает, имя файла должно

состоять не более чем из 8-ми символов. Расширение после сохранения

Бейсик ставит такое — bas. Запомним это, так нам будет легче искать

нужные файлы. Про форматы — верхний формат стоит по умолчанию. Убыстряет

работу с Бейсиком, может и размер файла будет немного меньше. Но зато

файлы, сохраненные таким образом, нельзя открыть ничем, кроме Бейсика, а

во-втором формате в файле просто будет текст написанного вами кода.

Такой файл можно открывать через любой редактор. Сохраните свою игру под

каким-нибудь именем. Теперь откроем меню загрузки: File ->

Open Program… Тут все почти тоже самое. Просто в большом окошке

выбираем нужный файл. Можно ввести название файла в верхнем окне и

Бейсик откроет его. А теперь о компилировании. Компилирование это,

по-простому, переделывание кода программы в простой EXE-файл. После

этого вы можете запускать свое детище отдельно от Бейсика и

где-угодно. Откроем меню компилирования Run -> Make EXE File…

В строке для ввода имени вводим нужное нам имя и переставляем

галочку на [ Stand-Alone EXE File] и жмем на [Make]. Откомпилируйте свою

игру под именем otstoy . При этом создадутся два файла. Один,

собственно, EXE-ник и файл с расширением OBJ. Он вам точно не нужен.

Можете его удалить.

9. Часть Девятая.

Немного об экранных режимах

Экранные режимы — это такие штуки, которые

определяют разрешение экрана (кол-во пикселов по гор-ли в вер-ли), а

также сколько символов (т.е. букв и цифр) вмещается в строку и

сколько будет столбцов. Ну еще и кол-во цветов. Режим определяется

оператором SCREEN n, где n — номер экранного режима. По умолчанию в

Бейсике стоит режим SCREEN 0. Этот режим единствнный из все только

текстовой. Т.е. в нам нельзя выводить графику. Кол-во символов,

вмещающихся в строке — 80, кол-во столбцов 25. Цветов шестнадцать.

Остальные режимы поддерживают графику. Например, режим SCREEN 12

поддерживает разрешение 640х480 и столько же цветов, а SCREEN 13

320х200, символов вмещается 40х25, но зато цветов — 256. Остальные

разрешения мы трогать не будем. Нам хватит и этих.

Сейчас мы научимся писать текст в нужном нам месте и

выбирать его цвет. Напишем следующий код. Знак [‘] означает комментарий,

т.е. после него вы можете писать какие-либо заметки. Бейсик при

исполнениии программы их не видит. Прочитайте комметарии в коде и

попробуйте сами все понять. Действуйте

‘Ставим 13-й экранный режим

SCREEN 13

‘Устанавливаем цвет №4, т.е. красный

COLOR 4

‘В 3 столбце с 17-го места в строке

пишем нужный текст

LOCATE 3,15: PRINT «Пишем вверху

посередине красным цветом»

‘Меняем цвет на зеленый и пишем внизу

экрана текст

COLOR 2: LOCATE 20, 1: PRINT

«Внизу слева зеленым цветом»

‘Завершение программы

END

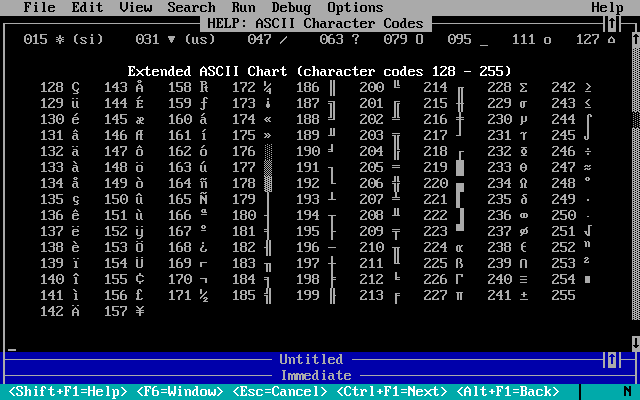

Теперь все должно быть понятно. Сейчас посмотрите

картинку, где показано какому цвету соответствуют цифры в операторе COLOR (только 16-ть цветов)

Прошу заметить, что цифра [0] соответствует черному цвету. И еще про LOCATE — все значения в операторе

начинаются с [1] а не с нуля, и если вы в нем напишите значения не

подходящие к заданному экранному режиму, то вылезет сообщение об ошибке.

Будте внимательней!

10. Часть Десятая.

Циклы. FOR и NEXT

А сейчас мы напишем программу, которая на

SCREEN 13 будет выводить по порядку 212 цветов и их цифровой код —

как это сделано на предыдущей картинке. Для этого нам понадобятся циклы.

Пишем код

SCREEN 13

FOR c=0 to 212

COLOR c: PRINT c;

NEXT c

END

Что же делает строка FOR c=0 to 212. Дословно она

означает то, что Бейсик прокручивает значение переменной c. Т.е. сначала

значение этой переменной равно 0, а когда Бейсик доходит до строки NEXT

c, то программа возвращается на вторую строку, но значение переменной

будет уже равно единице. И так будет продолжаться до тех пор, пока [c]

не будет равна 212. Третья строка текста: COLOR c — здесь просто вместо

цифры, мы подставляем значение переменной. Значит, цвет будет таким,

какое значение у переменной. PRINT c; — просто выводит подряд значения

переменной [c]. А почему же 212, если цветов 256? Все просто — потому

что только 212 вмещается на экране одновременно, если цифр будет больше

экран станет прокручиваться вниз и мы не увидим верхних строк. Что же

еще можно сделать с фором и некстом. А можно сделать так, чтобы значение

прибавлялось не на единицу а на большее число. Мы будем задавать шаг

цикла. Измените вторую строку на FOR

c=0 to 212 STEP 2 . STEP 2 означает то, что цикл будет повышать

значение переменной на 2 единицы сразу. Т.е. не 0,1,2,3, а 0,2,4,6,8. А

вот пример использования сразу двух циклов:

SCREEN 13

FOR y = 1 TO 25

FOR x = 1 TO 40 STEP 2

LOCATE y, x: COLOR x: PRINT «*»;

NEXT x, y

Красиво? То-то же. Разберитесь сами, зачем нам два цикла. Теперь о

правилах использовании нескольких циклов. В операторе NEXT на первом

месте должна стоять переменноа, которая указывается в самом последнем

операторе FOR. В нашем случае это переменная [x]. Сперва Бейсик

выполняет все условия цикла с [x], а потом переходит в цикл с [y] а

затем опять в цикл с [x]. Если разобраться и немного подумать, то все

это довольно просто.

11. Часть

Одиннадцатая. Введение в Графику — Кружочки, точки и прочая хрень

Сейчас самое время поработать с графикой. Вспомним такое понятие как

разрешение. Напомним, это кол-во пикселей на экране. Как уже было

сказано, разрешение для режима SCREEN 12 составляет 640х480. Запомним

это. Теперь рассмотрим оператор PSET, он имеет следующую структуру: PSET

(x,y),c

Этот оператор рисует точку (т.е. меняет цвет одного пиксела) с

координатами [x] и [y] цветом [c]. Следовательно, если мы введем

PSET(320,240),2 то получим зеленую точку в центре экрана. А

теперь, вспомнив материал о циклах, попробуйте наклепать программу,

которая будет рисовать в середине экрана точки с интервалом в 2 пикселя.

Надеюсь, на это у вас ума хватило. Теперь оператор LINE. Он может

нарисовать линию, если будет иметь следующий вид LINE (x1,y1)-(x2,y2),c

Первая пара координат с индексом [1] будет означать начало линии, а

вторая пара с индексом [2] конец ее. Т.е., если мы введем этот код:

LINE (0,0)-(50,50),4: LINE

(50,0)-(0,50),4

то Бейсик выведет на экран букву «Хэ». Если мы изобразим оператор так

LINE (x1,y1)-(x2,y2),c,b (b — это не переменная. Ее так и надо писать.

Она означает BOX ) то Бейсик будет выводить на экран незакрашенный

четырехугольник. Т.е. если мы подставим какие-либо координаты в оператор

с параметром b, а потом это b уберем, то получится диагональ этого

четырехугольника. А если мы изменим [b] на [bf], т.е. BOX FULL, то 4-х

угольник наш будет закрашенным. Теперь об окружностях. За это тут

отвечает оператор CIRCLE (x,y),r,c где x и y будут координатами центра

окружности, r — радиус и c — надо полагать, — цвет. Теперь немного про

эллипсы. Вид эллипса будет определяться следующим соотношением : Ry/Rx,

т.е. радиус по [y] на радиус по [x] И для того, чтобы нарисовать

эллипсы, вытянутые по вертикали, это соотношение должно быть от 0 до 1,

а для эллипсов, вытянутых по горизонтали, оно должно быть больше 1. Сам

оператор будет выглядеть так: CIRCLE(x,y),r,c, , , k, где [k] — это и

есть значение нашего соотношения. Теперь вам надо просто научиться

ориентироваться в системе координат. Побольше тренируйтесь — это вам

поможет, потому что больше вам уже ничего не поможет. А сейчас оператор

закраски. Нарисуем в середине экрана окружность с координатами 320,240 ,

радиусом 50 и цветом 2. А затем добавим такую строку PAINT(x,y),c1,c2

Она означает: в точке с заданными координатами цветом c1 закрасить всю

область, имеющую контур с цветом c2. Надо помнить, что оператор PAINT

закрашивает только замкнутые контуры цвет которых совпадает с

показателем c2. Т.е. мы в нашей строке меняем координаты на те, в которые

входит наша окружность, например 310 и 245, а c1 на, допустим 4, а c2 —

на 2. И смотрим, что получается. С этим оператором могут быть большие

проблемы из-за невнимательности к замкнутости контура и его цвета.

Повнимательней, люди!

12. Часть

Двенадцатая. DRAW — красиво и быстро

Сейчас мы разберем очень хороший оператор DRAW, с

его помощью можно рисовать довольно сложные изображения — было бы

желание. А теперь прочитайте внимательно эту таблицу:

| Ux | Переместиться на x точек вверх |

| Dx | Переместиться на х точек вниз |

| Lx | Переместиться на х точек влево |

| Hx | Переместиться на х точек вправо |

| Hx | Переместиться на х точек вверх и влево |

| Ex | Переместиться на х точек вверх и вправо |

| Gx | Переместиться на х точек вниз и влево |

| Fx | Переместиться на х точек вниз вправо |

| M+-x,+-y | Переместиться на + или — x точек по горизонтали и на + или — y точек по вертикали. Не забудьте проставлять [+] и [-] ! |

| M x,y | Переместиться в точку с координатами x и y |

| Cx | Задание цвета. Это цвет будет сохраняться до введения новой команды |

| Pc1,c2 | Команда закраски. c1 и c2 имеют то же значение, что и в операторе PAINT |

| B | Переместиться на новое место, указанное в следующем за B параметре, но РИСОВАНИЕ не производить |

| N | Выполнить следующую за N команду по перемещению в новое место, а затем вернуться на предыдущую позицию |

Это почти все параметры оператора DRAW. Сам оператор имеет следующую

структуру: DRAW «—праметры—» Т.е. для того, чтобы нарисовать куб со

строной в 50 и закрасить его в красный цвет, мы введем следующий код:

DRAW «C2 R50 D50 L50 U50 B F25 P4,2». Разберем это поэтапно: назначаем

цвет №2, перемещаем курсор на 50 точек вправо, затем вниз, потом влево и

затем вверх. Теперь после команды B курсор переходит без рисования на 25

точек вниз и вправо, а затем закрашивает наш квадрат с контуром цвета №2

цветом №4. По умолчанию DRAW выводит изображение на середине экрана.

Чтобы нарисовать изображение в нужной позиции добавим в начало строки

команду Mx,y, где и выбираем нужные координаты. После драв можно ставить

не само выражение, а строковую переменную, т.е. :

a$= «C2 R50 D50 L50 U50 B F25 P4,2»:

DRAW a$

Оператору все-равно большими или маленкими буквами стоят параметры, а

также есть ли между ними промежутки. Можно комбинировать переменные или

выражения в строке DRAW при помощи знака [+]:

a$= «C2 R50 D50 L50»

b$=»U50 B F25 P4,2″

DRAW «m1,1″+a$+b$

С помощью DRAW можно рисовать довольно сложные

изображения. Они будут быстро выводиться на экран и занимать мало места.

Только надо тренироваться, чтобы запомнить и приноровиться к командам

этого оператора.

14. Часть

Четырнадцатая. Эффект движения

Как же нам иммитировать движение на Бейсике. Самый

простой и распространненный способ состоит в следующем: рисуем

изображение, стираем его, потом рисуем изображение, но уже на новом

месте. Стирать и рисовать надо черех определенный промежуток времени,

т.е. от этого будет зависить скорость движения. За время в Бейсике

отвечает оператор SLEEP n, где n — время в секундах. Этот оператор плох

тем, что не может отсчитывать время меньшее чем 1 сек. А если нам не

ставить после SLEEP число, то Бейсик будет ждать все жизнь, пока

вы не нажмете какую-либо клавишу. Сейчас мы сделаем программу, которая

рисует движущуюся точку со скоростью пиксел в секунду:

SCREEN 13

FOR x=0 to 310

‘Рисуем точку с цветом 4

PSET(x,120),4

‘Ждем одну секунду

SLEEP 1

‘В точке с теми же координатами

рисуем точку черным цветом, т.е. стираем ее

PSET(x,120),0

‘Цикл каждый раз добавляет к

переменной x единицу

NEXT x

Усе. Надеюсь все понятно. Попробуйте заменить точку на окружность.А

потом на закрашенную окружность.

15. Часть

Пятнадцатая. Опрос клавиатуры

Выполним следующий код:

‘Задаем начальные значения для

переменных

x = 159: y = 100: c = 1

‘Задаем экранный режим

SCREEN 13

‘Рисуем окружность с заданными

координатами и цветом

CIRCLE (x, y), 4, c

‘Начала безусловного цикла

DO

‘Задание строковой переменной k$

значения системной переменной INKEY$

k$ = INKEY$

‘Действия при нажатых клавишах

IF k$ = «w» AND y > 5 THEN CIRCLE

(x, y), 4, 0: y = y — 2: GOSUB ReDraw

IF k$ = «s» AND y < 190 THEN

CIRCLE (x, y), 4, 0: y = y + 2: GOSUB ReDraw

IF k$ = «a» AND x > 5 THEN CIRCLE

(x, y), 4, 0: x = x — 2: GOSUB ReDraw

IF k$ = «d» AND x < 310 THEN

CIRCLE (x, y), 4, 0: x = x + 2: GOSUB ReDraw

IF k$ = «c» AND 0 < x <

256 THEN c = c + 1: GOSUB ReDraw

‘Конец безусловного цикла

LOOP

‘Начало подпрограммы ReDraw

ReDraw:

CIRCLE (x, y), 4, c

‘И ее же конец

RETURN

Во-первых, переключитесь на английский язык и

выключите Caps Lock. Ну, как всегда, здесь много всего непонятного и

загадочного. По порядку: задаем переменным x и y значения (можно

догадаться, за что они отвечают), а также задаем его и переменной с,

которая у нас будет отвечать за цвет нашего объекта. Далее экранный

режим, рисование окружности… ну это нам уже известно. А теперь новое:

оператор DO … LOOP. Все просто — все команды, которые стоят между

этими словами, будут выполняться в цикле бесконечно. Что нам и нужно.

Идем дальше. Строка k$ = INKEY$ делает вот что: теперь переменная

k$ у нас будет отвечать за нажатые клавишы. Сейчас все поймете.

Следующая строчка это иллюстрирует: ЕСЛИ k$=»w» ТО … Одним словом,

если k$=»какой-то клавише», то выполнится все, все…эээ, что

написано после. Сейчас разберем смысл всей строки: IF k$ = «w» AND y

> 5 THEN CIRCLE (x, y), 4, 0: y = y — 2: GOSUB ReDraw. Сначала

проверяем, если нажата клавиша [w] и пременная y больше пяти (AND

обозначает [И], т.е. если не будет выполнено условие, стоящее после AND,

то оператор не выполнит указанные действия), то рисуем в точке с

заданными координатами тот же круг, но черного цвета, т.е. как бы

«стираем» предыдущий, «цветной» круг. Затем изменяем координату, а потом

новая для вас команда GOSUB. Это что-то вроде GOTO, только лучше

(вообще, использование GOTO считают неким дурным тоном в

программировании, поэтому его лучше не использовать, да и новый оператор

гораздо удобнее во многих случаях). Он вызывает подпрограмму, в данном

случае, ReDraw. Посмотрите в конец программы. Там есть строчка ReDraw:

(не забудьте про двоеточие). Т.е. подпрограмма назначается так же как и

метка в операторе GOTO. После команды Gosub ReDraw Бейсик ищет начало

подпрограммы, выполняет все команды в ее теле, а после ее конца (а она

всегда закачивается словом RETURN) ВОЗВРАЩАЕТСЯ (это важно!), опять к

тому месту, где стоит вызвавший ее GOSUB. Т.е получается то, что после

GOSUB программа переходит в подпрограмму (вынужденная тавталогия,

однако:) ), которая рисует круг с новыми координатами и цветом, а затем

возвращается в начало. Все. Строчка отвечающая за обработку нажатия

клавиши [c], как вы уже догадались, отвечает за изменение цвета, причем

ограничение AND 0 < x < 256 сделано для того, чтобы вы не могли

назначить цвет за пределами возможных в этом экранном режиме. И сразу

после этого опять идет вызов подпрограммы, чтобы эффект от перемены

цвета был виден сразу после нажатия на [c], а не после нажатия на

клавиши, отвечающие за движение. Еще одно важное замечание: IF k$ = «w»

отвечает только за нажатие клавиши [w], а не за [W] или [ц]. Если вы

хотите избежать этого, то просто напишите IF k$ = «w» OR k$ = «W» OR k$

= «ц» OR k$ = «Ц» OR … и так далее. OR означает [ИЛИ], т.е. если один

из этих вариантов имеет смысл, то оператор пойдет выполнять свои

инструкции дальше. Так, что еще… ах да! Стоит отметить, что

ограничения вроде x < 310 или y > 5 сделаны для того, чтобы

окружность не выходила за пределы экрана. Вникните, разберитесь что к

чему. Попробуйте изменить что-нибудь или добавить нового. Сейчас

вы уже вполне можете сделать какую-нибудь простенькую игру, вроде Quake

или WarCraft. Но не будем же мы забивать себе голову этими попсовыми

делами!

P.S. Нет, все-таки забыл кое-что. А как же нам

использовать клавиши движения курсора или ESC с Enter’ом? Давайте

воспользуемся следующим кодом, мы не будем вдаваться в подробности,

просто примите это как данное:

DO

k$ = INKEY$

IF LEN(k$) = 2 THEN

code = ASC(MID$(k$, 2, 1))

IF code = 72 THEN PRINT «Вверх»

IF code = 80 THEN PRINT «Вниз»

IF code = 75 THEN PRINT «Влево»

IF code = 77 THEN PRINT «Вправо»

ELSE

IF k$ = CHR$(27) THEN PRINT «[ESC]»

IF k$ = CHR$(13) THEN PRINT «[ENTER]»

END IF

LOOP

16. Часть

Шестнадцатая. Генератор случайных чисел

Вводим код:

SCREEN 13

‘Цикл, повторяющийся тысячу раз

FOR i = 1 TO 1000

‘Задаем переменным значения с помощью

генератора случайных чисел

x = INT(RND(1) * 320): y = INT(RND(1)

* 200): c = INT(RND(1) * 256)

‘Рисуем точку с заданными

координатами и цветом

PSET (x, y), c

NEXT i

Что такое генератор случайных чисел (ГСЧ) и зачем он

нужен? Это специальный оператор, который выдает какое-либо случайное

число из заданного диапазона. Он имеет следующий синтаксис (он может

иметь и другой, но мы рассматриваем только этот, т.к. он самый

практичный): RND(1)*n. Рассмортрим пример. Если мы введем

a=RND(1)*5, то компьютер будет выдавать числа в районе от 0 до 4.[9]

(вдумайтесь: от 0 до 4.[9], а не до 5!). Только будет он их выдавать в

несколько неподходящем формате, а именно с многими цифрами после

запятой, вроде 3.1748583890 и т.п. Чтобы избежать этого мы воспользуемся

командой INT, которая округляет полученное выражение (заметьте, что все

выражение стоит в скобках. Т.е. INT округляет выражение, стоящее в

скобках), и на выходе буду получаться только цифры: 0,1,2,3 и 4.

Надеюсь, вы уже поняли принцип вышеописанной программы. Она, с помощью

RND, рисует 1000 точек в случайном месте и случайным цветом. А что если

надо получить числа в промежутке от 1 до 5. Просто пишем так:

a=INT(RND(1)*5)+1. Все просто, однако. Только тут надо запомнить еще

одну вещь. Сейчас числа выдаются не совсем случайным образом, чтобы уж

точно сделать их случайными вы должны в начале программы написать

строчку RANDOMIZE TIMER. После этого Бейсик будет генерировать

случайные числа, основываясь на показаниях таймера компьютера.

17. Часть

Семнадцатая. Вторая игра.

Подошло время написать вторую игру. Но она уже будет

действительно на нее похожа. В этой игре нужно ловить «ракеткой» подобие

шарика (точки, которая быстро падает вниз). Причем коодринаты шарика

всегда выдаются случайными и надо приловчиться, чтобы ловить их. Причем,

если шарик подвести к краю экрана, то он окажется на другой его стороне.

Это нужно, чтобы ловить «далекие» шарики. Все команды, кроме одной, вам

известны, просто надо обдумывать каждую строчку и прикидывать зачем она

тут нужна. Давайте разберемся с новой командой POINT. Она имеет

следующий синтаксис POINT(x,y). Рассмотрим фрагмент кода: IF POINT(xB,

yB + 1) = 0… Этот оператор возвращает значение цвета в точке с

заданными координатами. Т.е., в нашем случае получается, что ЕСЛИ в

точке с координатами xB,yB+1 экран будет черного цвета, то дальше пойдет

выполняться условие. Это очень нужный оператор. С помощью него вы

можете легко реализовать проверку на столкновения. Вводим код:

SCREEN 13

‘Задание значений таймера для

генерации случайных чисел

RANDOMIZE TIMER

‘Задание переменным значений

x = 110: yB = 10: xB = 100: Live = 5

‘Первичная прорисовка ракетки и

интерфейса, чтобы все эти элементы были видны сразу

LINE (x, 170)-(x + 10, 175), 2, BF

LOCATE 23, 1: PRINT «Жизни:»; Live;

«Очки:»; Score; «[ESC]-В

‘Начало безусловного цикла

DO

‘Стираем шарик, перемещаем его и

опять рисуем

PSET (xB, yB), 0: yB = yB + .0005:

PSET (xB, yB), 4

‘Если шарик уже на уровне ракетки, то

проверяем его на столкновение с ракеткой, а затем создаем новый шарик

IF yB >= 169 THEN GOSUB Coll:

GOSUB NewBall

‘Уже знакомые нам команды

k$ = INKEY$

IF LEN(k$) = 2 THEN

code = ASC(MID$(k$, 2, 1))

IF x > 320 THEN GOSUB Del: x = 0

IF x < -4 THEN GOSUB Del: x = 320

IF code = 75 THEN GOSUB Del: x = x —

3: GOSUB ReDraw

IF code = 77 THEN GOSUB Del: x = x +

3: GOSUB ReDraw

ELSE

‘При нажатии [ESC] переходим на метку

GameOver

IF k$ = CHR$(27) THEN GOTO GameOver

END IF

‘Конец цикла

LOOP

‘Подпрограмма рисования ракетки

ReDraw:

LINE (x, 170)-(x + 10, 175), 2, BF

RETURN

‘Подпрограмма стирания ракетки

Del:

LINE (x, 170)-(x + 10, 175), 0, BF

RETURN

‘Подпрограмма проверки на

столкновение шарика с ракеткой

Coll:

‘Если в нужной точке цвет равен 0,

т.е. он черный, значит там нет ракетки и кол-во жизней уменшается на одну

‘А если он не равен 0, то,

следовательно, он столкнулся с рокеткой и игрок получает 50 очков

IF POINT(xB, yB + 1) = 0 THEN Live =

Live — 1 ELSE Score = Score + 50

‘А это строка нужна для стирания с

поля «мертвых» шариков, т.е. уже упавших

PSET (xB, yB), 0

‘Если кол-во жизней меньше нуля, то

переход к метке GameOver

IF Live < 0 THEN GOTO GameOver

‘Обновление интерфейса

LOCATE 23, 1: PRINT «Жизни:»; Live;

«Очки:»; Score; «[ESC]-Выход»

RETURN

‘Подпрограмма создания нового шарика

NewBall:

xB = INT(RND(1) * 315) + 1: yB =

INT(RND(1) * 50) + 1

RETURN

‘Метка, после которой идет вывод

результата игры и завершения программы

GameOver:

CLS

COLOR 2: LOCATE 3, 15: PRINT «Конец

Игры»

LOCATE 8, 15: PRINT «Очки:»; Score

END

Еще одно. У вас шарик может двигаться недостаточно

быстро, или наборот, предостаточно быстро. Для корректировки скорости

меняйте число в этом коде: yB= yB + .0005. При увеличении числа,

шарик станет медленнее, при уменьшении… ну вы уже поняли.

18. Часть

Восемнадцатая. Музыка и Звуки.

Все, что мы делали прежде, происходило в полной

тишине. Сейчас мы научимся «озвучивать» наши программы. Бейсик

использует для выода звука не какой-нибудь там Sound Blaster, а

встроенный динамик — бипер (тот, который пищит при загрузке). Для звука

есть два оператора: SOUND и PLAY. Первый используется для подачи звука

определенной частоты и длительности, а второй использует макроязык,

похожий на DRAW, и позволяет работать непосредственно с нотами. Разберем

SOUND. Синтаксис следующий: SOUND f, t, где f -частота в Гц (от 37 до

32.767), а t — длительность в тиках (18.2 тика — 1 сек. Диапазон: от 0

до

65.535). Введите этот код; звук будет напоминать нарастающий рев мотора:

FOR x = 100 TO 200

SOUND x, .5

NEXT x

А теперь про PLAY. Синтаксис как у DRAW: PLAY

«Набор-Команд». Введите следующий код: PLAY «T180 o2 P2 P8 L8 GGG L2 E-

P24 P8 L8 FFF L2 D». Прозвучат первые несколько секунд из Бетховена.

Кстати, на моем сайте вы можете найти немного PLAY’евской музыки.

Конечно, можно присвоить значение этой мелодии строковой переменной.

Вроде: a$= «T180 o2 P2 P8 L8 GGG»: PLAY a$. Ниже перечислены команды

оператора PLAY:

Ноты задаются буквами A,B,C,D,E,F,G, # означает

диез, а — бемоль, т.е B# ре-диез, а B- ре-бемоль

| On | Выбор октавы, где n -ее номер. |

| Tn | Задание темпа или четвертных нот, которые исполняются в минуту. n от 32 до 255. По умолчанию 120 |

| Pn | Задание паузы длительностью 1/n. n от до 64 |

| Nn | Исполнение ноты n, которая может меняться от 0 до 84. Каждая октава имеет 12 нот, включая диезы и бемоли. 0 — пауза |

| Ln | Исполнение последующих нот с интервалом 1/n. n от 1 до 64 |

| MN | Нормаль. Каждая нота звучит 7/8 времени, заданного в команде L |

| ML | Легато. Каждая нота звучит полный интервал времени, заданного в команде L |

| MF | Стаккато. Каждая нота звучит 3/4 времени, заданного в команде L |

| MS | Режим непосредственного исполнения. Т.е. на время проигрывания ноты программа приостанавливается. Используется по умолчанию |

| MB | Режим фонового исполнения. Т.е. проигрывание нот не приостанавливает действие программы |

| . (точка) | Увеличение продолжительности звучания на 50% |

19. Часть

Девятнадцатая. Продвинутая графика: GET и PUT

Вы, конечно, наивно думаете, что с помощью всяких LINE, PSET и даже

DRAW сможете нарисовать какие-либо серьезные и красивые изображения. Но

когда надо сделать действительно хорошую графику (например, в играх:

изображение игрока или врагов), то надобно использовать ооманды GET и

PUT. Только для их применения надо разобрать еще несколько команд.

Вводим код:

SCREEN 12

‘Создаем массив с именем Tank,

длинной в 100

DIM Tank(100)

‘Вводим данные нашего танка

DATA 8,8,8,0,8,8,0,8,8,8

DATA 8,7,8,0,8,8,0,8,7,8

DATA 8,7,8,0,8,8,0,8,7,8

DATA 8,7,8,8,8,8,8,8,7,8

DATA 8,7,8,7,7,7,7,8,7,8

DATA 8,7,8,7,8,8,7,8,7,8

DATA 8,7,8,7,8,8,7,8,7,8

DATA 8,7,8,7,7,7,7,8,7,8

DATA 8,7,8,8,8,8,8,8,7,8

DATA 8,8,8,0,0,0,0,8,8,8

‘Два цикла, отвечающие за считывание

данных и отображения их на экран

FOR y = 0 TO 9: FOR x = 0 TO 9

‘Считываем данные из операторов DATA;

выводим точки с заданными координатами и цветом (который взят из данных

DATA)

READ c: PSET (x, y), c: NEXT x, y

‘Заносим в массив Tank изображение

нашего танка

GET (0, 0)-(9, 9), Tank

‘Стираем экран, выводим с помощью PUT

изображение танка в указанном координатами месте

CLS: y = 470: PUT (320, y), Tank

‘Начало цикла

DO

k$ = INKEY$

‘При нажатии [w] стирание

изображения, с помощью наложения такого же в те же координаты, изменение

координаты y,

‘И перерисовка изображения на новом

месте

IF k$ = «w» THEN PUT (320, y), Tank:

y = y — 3: PUT (320, y), Tank

‘Конец цикла

LOOP

Что такое DATA и что за цифры после него? Все

просто. Это, так сказать, цифровое отображение нашего танка. Т.е. цифры

соответствуют номеру определенного цвета. Но «рисовать» таким образом в

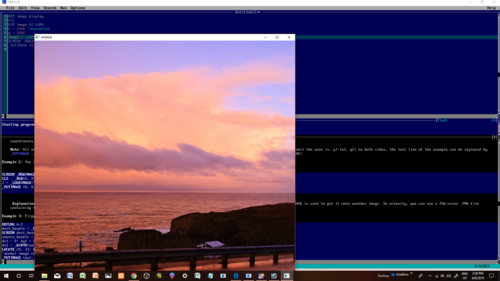

Бейсике — изврат чистой воды. Поэтому делаем вот что. Запускаем

стандартный Windows’ский Paint, создаем небольшое изображение (в нашем

случае 10×10 пикселей), потом сохраняем файл как 16-цветный рисунок,

далее увеличиваем масштаб до максимума, и в меню [Вид]->[Масштаб]

выбераем [Показать Сетку]. Теперь рисуем. Какой номер соответствует

какому цвету было уже описано и показано вверху. Наш танк выглядит вот

так:

Теперь переводим это в форму, понятную Бейсику, т.е. в оператор DATA.

Считать данные можно оператором READ n, где n — переменная, которая

принимает значение данных в операторе DATA. Но у нас 100 значений,

поэтому мы прокручиваем их с помощью двух циклов (заметьте, циклы

начинаются от 0 до 9, но у нас изображение 10×10. Это связано с тем, что

0 тоже входит в эти числа. Просто мы начинаем с 0 для того, чтобы

изображение наше начало выводиться с самого начала координат). При

прохождении этих циклов оператор READ поэтапно считывает все данные с

DATA, а при считывании каждый раз, с помощью PUT, мы каждый раз рисуем

точку с координатами x и y и цветом c. Переменная c, как вы поняли, и

принимает значения данных с оператора DATA.

Теперь непосредственно об самих операторах GET и

PUT. Оператор GET заносит в массив выбранную часть экрана. Сейчас мы

немного коснемся массивов. В начале программы мы создаем массив с именем

Tank и размером в 100 ячеек, т.е. это вроде переменной, но которая может

хранить очень много значений, в нашем случает это 100. Т..е 100 хватит,

чтобы считать область экрана размером 10×10 (10*10=100). Задается

массив так: DIM Name(n), где Name — имя массива, а n- количество ячеек

в нем. Если надо задать, например больше одного массива, то можно в

одном операторе DIM перечислить их через запятую: DIM one(100),

two(200), free(300) и т.д. Вернемся к GET. Оператор имеет следующий

синтаксис: GET (x1,y1)-(x2,y2),Name. С координатами тут как в LINE,

т.е. две пары координат и создают область экрана, которую надо считать.

GET считывает изображение с экрана и записывает его в массив Name.

Только надо следить за тем, чтобы размера массива хватило на тот

участок экрана, который считывается. Например, если бы мы в нашей

программе сделали бы массив Tank размером, например, 90, то вылезло бы

сообщение об ошибке. Будте Бдительны!. Теперь о PUT. Он выводит

изображение на экран, сохраненное в массиве. Его синтаксис: PUT

(x,y),Name. x,y — координаты левого верхнего угла, с которого и будет

начинаться строиться изображение, Name — имя массива, содержащего нужное

изображение. Но, стоит отметить, в отличие, например, от оператора LINE,

где мы стирали изображение черным прямоугольником, здесь изображение

стирается простым наложением того же изображения. Т.е. две команды PUT,

идущие вместе: PUT (320, y), Tank: PUT (320, y), Tank, сотрут

изображение.

20. Часть Двадцатая.

Проблемы и Дополнения.

Все. Практическая часть этой книги закончена. Она не раскрывает и 1/10

всех возможностей QBasic’a, но она позволит с чего-то начать. Если вы

хотите и дальше развиваться в этом направлении, то я бы посоветовал вам

приобрести книги по QBasic’y. Выбрать себе книги можно здесь http://quitbasic.narod.ru/book.html

Лично я посоветовал бы вам книгу, с которой я

сам начинал. Это книга И. Сафронова «Бейсик В Задачах И Примерах’. На

вышеприведенной ссылке эта книга тоже есть. Также на моем сайте http://quitbasic.narod.ru можно

найти различную справочную информацию и скачать множество игр,

программ, утилит для QBasic’a.

Теперь о проблемах. Часто программы под Бейсиком

используют мышь, но чтобы вы могли нормально запустить эту программу,

вам надо использовать стандартную библиотеку, поставляемую с

Бейсиком . Делается это так: создаем в папке с Бейском файл с

расширением BAT (Если у вас не отображаются расширения, то зайдите в

меню [Свойства Папки] и уберите галочку с пункта [Скрывать расширения

для зарегистрированных типов файлов]). Просто создайте новый файл,

откройте этот файл с помощью Блокнота и напишите Name.exe/q, где Name

-имя файла, который у вас запускает Бейсик. Просто иногда они бывают

разными, вроде QB.exe или QBasic.exe. Сохраните файл и запускайтесь

через него. Все должно заработать. Другая проблема, более серьезная,

это корректное отображение русского языка в Бейсике. При использовании

MS-DOS и WIN95-98 никаких проблем не возникнет. А вот, например, в WIN

Me, при SCREEN 13 или SCREEN 9, русский язык отображаться не будет. Про

системы типа WIN2000 или XP я вообще молчу. Чтобы избавиться от этой

проблемы, надо использовать программу-русификатор KeyRus. Взять ее

можно, например здесь

http://quitbasic.narod.ru/file/keyrus.zip . Весит она в архиве всего

12 кб. Для использования этой программы воспользуйтесь тем же BAT

файлом, просто первой строчкой пропишите в нем вот это: keyrus Но,

естественно, сам файл с программой KeyRus должен быть в одной

папке с Бейсиком. Но есть еще одна проблема, более фатальная. Она

характерна для ОС вроде WIN2002 или XP. На этих системах Бейсик имеет

обыкновение жутко глючить и подвисать. Также открытое окно Бейсика,

впрочем, как и любой другой DOS-программы, очень тормозит систему. И

еще: если вы запустите Бейсик, то окно его, развернется на полный экран,

причем все будет маленькое и неудобное. Про русские буквы можно и не

упоминать… Чтобы хоть этого не было, надо выбрать в свойствах

исполняемого файла Бейсика пункт, который будет называться вроде

[Запускать в окне]. Если вы после этого запустите Бейсик, то он будет в

окне. Теперь просто разверните его на всеь экран (Alt+Enter) и все

должно быть нормально. Но запуск QBasic’a под этими системами — это

большая проблема. Имейте это в виду.

На этом все. Все замечания и предложения прошу доставлять на maxim1441@yandex.ru

10.07.04 Максим Речков.

Среда программирования QBasic.

Бейсик (Basic) — диалоговый учебный

язык программирования для персональных компьютеров. На современных

компьютерах используется следующие версии Basic: GWBasic, QBasic 4.5,

Turbo Basic для DOS, Visual Basic 3.0-6.0 для Windows. Здесь мы

рассмотрим QBasic 4.5.

QBasic входит в состав операционной системы MS-DOS 6.0-6.22. Есть русифицированная версия QBasic.

Для запуска QBasic надо или найти файл qbasic.exe и Enter, или ввести в командную строку qbasic и Enter. Меню — Alt.

Запуск программы Shift-F5.

Получение помощи Shift-F1.

Создать файл: Меню Файл, Сохранить Как, выбрать каталог, задать имя файла, ОК. Файл получит расширение bas.

Сохранить файл: Меню Файл, Сохранить.

Открыть файл, то есть считать его с диска: Меню Файл, Открыть.

Выход из QBasic: Меню Файл, Выход.

Копирование выделенного фрагмента программы в буфер (Edit,Copy) — Ctrl-Insert,

Вставка фрагмента из буфера (Edit,Paste) — Shift-Insert,

Вырезать (Edit,Cut) — Shift-Delete.

Удобно выделять и делать все

указанные операции с помощью мыши. Можно выделенный фрагмент программы

вставить в другой файл, если после выделения открыть его.

В QBasic 4.5 можно

откомпилировать текстовый bas-файл, превратив его в двоичный exe-файл,

который можно использовать отдельно, то есть без среды программирования

QBasic.

Переменная в программе

Переменная — это область в памяти компьютера, где хранится некоторое значение. Каждая переменная имеет имя, значение и тип.

Имя переменной обозначается

английской буквой, после которой может быть цифра, причем первой стоит

буква, например: x, y, z, A1, B2. Имя переменной служит для обозначения

некоторой величины в программе, которая при выполнении программы может

иметь какое-либо значение, но может быть и не определена. Пример

задания часто употребляемой константы: pi=3.14159.

Типы переменых:

целая, вещественная, логическая, символьная, строковая и др. Если в

переменной хранится число, то это числовая переменная, если в

переменной хранится слово или фраза, то это строковая (символьная)

переменная. В QBasic строковая переменная обозначается a$, b$ (в конце

имени стоит знак доллара $). Содержимое хранится в переменной, до тех

пор, пока оно не будет специально изменено.

Операция предачи новых данных в переменную называется присваиванием и обозначается в QBasic знаком «=», например, x=10.

Некоторые основные директивы QBasic

Директива REM или апостроф ‘ —

обозначает комментарий к программе или команде. Вся строка (как

правило, это поясняющий текст), что идёт после знака комментария, не

исполняется. Этот знак используется при отладке программ.

Оператор CLS-оператор очистки экрана. С него часто начинаются программы, работающие в текстовом режиме.

Директива END означает конец программы. Применение этой команды в конце программы не является обязательным.

Все формулы в QBasic записываются в строку, при этом используются следующие математические знаки:

«+» и «-» — сложение и вычитание;

«*» и «/» — умножение и деление;

«^» — возведение в любую степень;

(x+3.14)/(a+b) — используются только круглые скобки и десятичная точка вместо запятой.

Пример: S=Vo*t+g*t^2/2

В QBasic применяются следующие встроенные функции:

SQR(X) — извлечение квадратного корня;

ABS(X) — модуль (абсолютная величина) числа;

SIN(X); COS(X); TAN(X) — тригонометрические функции синус, косинус и тангенс угла в радианах;

ATN(X) — арктангенс числа в радианах;

INT(X) — округление числа (дробная часть числа отбрасывается);

RND(X) — случайное число;

z = y MOD x — целый остаток от деления y на x.

LOG(X) — логарифмическая функция (натуральный логарифм по основанию e=2.71828);

EXP(X) — показательная (экспоненциальная) функция.

Операции ввода-вывода информации

Для вывода (печати) информации на экран применяется оператор PRINT. Пример:

PRINT X — вывод на экран значения числа X.

PRINT «Скорость тела равна:

V=»; V; «м/с» — выводимый на экран текст указывается в кавычках. Вместо

знака «;» можно ставить знак «,».

Просто оператор PRINT без текста и знаков даёт пустую строку на экране.

Если при работе в среде

QBasic 4.5 вместо слова PRINT ставить знак вопроса «?», а затем нажать

Enter, то слово PRINT само появится на экране. Это упрощает работу

программиста.

Ввод данных с клавиатуры осуществляется с помощью оператора INPUT

Пример: INPUT X — ввод числа X. На экране появится знак «?» и компьютер ждёт ввода переменной Х (это приглашение ввести число).

INPUT «Введите число Х=»; X —

можно вводить в кавычках подсказку, она будет выводиться на экран.

После подсказки можно ставить знак «,» вместо знака «;», но тогда знака

вопроса «?» на экране не будет, а вместо него в качестве приглашения

будет мигать курсор.

Пример 1: Вычислить площадь треугольника по формуле Герона.

CLS

‘Определите площадь треугольника по формуле Герона.

INPUT «Введите величину стороны a: a=», a

INPUT «Введите величину стороны b: b=», b

INPUT «Введите величину стороны c: c=», c

p = (a + b + c) / 2

S = SQR(p * (p — a) * (p — b) * (p — c))

PRINT «Ответ: площадь треугольника равна: S=»; S

Пример 2 (с использованием строковых переменных). Напечатайте на экране введённые с клавиатуры фамилию, имя и класс ученика.

CLS

INPUT «Введите свою фамилию: «, f$

INPUT «Введите своё имя: «, i$

INPUT «Введите свой класс: «, k$

PRINT f$; » «; i$; «, «; k$

END

Управляющие конструкции QBasic

1. Оператор безусловного перехода

GOTO N, где N-метка. В качестве N можно взять любое число, не

обязательно совпадающее с номером строки, так как в QBasic 4.5 строки

можно не нумеровать. Но двух одинаковых меток в одной программе не

должно быть. Исполнение программы будет продолжено с той её части,

которая начинается с указанной метки.

Пример:

…….

GOTO 10

…….

10 PRINT «Текст»

…….

2. Условный оператор IF…THEN…ELSE (Если…Тогда…Иначе):

IF <условие> THEN <список операторов> ELSE <список операторов>

Если заданное условие

истинно, выполняется список операторов, стоящий после THEN, в противном

случае выполняется список операторов, стоящий после ELSE.

Слово ELSE может и отсутствовать. Тогда происходит переход к строке, следующей за оператором IF…THEN.

Условия представляют собой

логические соотношения: равенства или неравенства = равно, <>

неравно, > больше, < меньше, >= больше или равно, <= меньше

или равно.

При использовании сложных

условий (объединении двух и более условий) применяют слова AND (И) и OR

(ИЛИ): Условие1 AND (или OR) Условие2…

Условный оператор позволяет реализовать алгоритм с ветвлением.

Пример 1:

CLS

INPUT «Введите год основания Москвы: M=»; M

IF M = 1147 THEN PRINT «Вы правы!» ELSE PRINT «Вы ошиблись!»

Пример 2:

CLS

PRINT «Вычислите y=1/(x-2) для всех x»

INPUT «Введите x=», x

IF x = 2 THEN PRINT «При x=2 функция не определена!»: END

y = 1 / (x — 2)

PRINT «y=»; y

Применяется также частный

случай условного оператора — оператор условного перехода: IF

<условие> GOTO N ELSE <список операторов> Число N — метка.

Если условие выполняется, то происходит переход по метке N, а иначе

выполняется список операторов, стоящих после ELSE. Слово ELSE может и

отсутствовать. Тогда происходит переход к строке, следующей за

оператором IF…GOTO.

Пример 3:

CLS

INPUT «Если хочешь каникулы, вводи 1. Если нет, любое число. n=», n

IF n = 1 THEN GOTO 10 ELSE GOTO 20

10 PRINT «Хочу каникулы!»: END

20 PRINT «Хочу учиться!»

3. Оператор цикла

FOR…TO…NEXT… позволяет реализовать циклический алгоритм, когда

часть программы может быть выполнена много раз подряд. FOR…TO… —

начало цикла, NEXT… — конец цикла.

То, что стоит между началом и

концом цикла, называется телом цикла. Иногда также применяются

вложенные циклы, то есть циклы могут быть вложенными один в другой.

FOR X=A TO B STEP H

……………….

NEXT X

Здесь X — переменная, A —

начальное значение переменной, B — конечное значение переменной, H —

шаг, с которым меняется переменная. Если шаг STEP H отсутствует, то по

умолчанию шаг H=1. При этом переменная X называется счётчиком цикла.

Повторение участка программы с шагом H происходит до тех пор, пока

X<B. Число повторений цикла равно (B-A)/H. При X=B цикл

заканчивается и выполняется оператор, следующий за оператором конца

цикла NEXT. Возможно, что шаг H<0, но тогда A>B.

Пример 1: Напечатать на экране текст 20 раз.

CLS

FOR X=1 TO 20

PRINT «С Новым Годом!»

NEXT X

Пример 2: Вычислить сумму n первых членов ряда S=1+1/4+1/9+…+1/n^2

CLS

INPUT «Введите число членов ряда: n=», n

FOR i = 1 TO n

S = S + 1 / i ^ 2

NEXT i

PRINT «Сумма n первых членов ряда равна: S=», S

Пример 3: Нарисуйте 15 разноцветных концентрических окружностей.

SCREEN 7

FOR i = 1 TO 15

CIRCLE (160, 100), i * 6, i

NEXT i

Пример 4: Разлинуйте экран в клеточку.

SCREEN 7

FOR i = 1 TO 32

LINE (0, 10 * i)-(320, 10 * i), 15

LINE (10 * i, 0)-(10 * i, 200), 15

NEXT i

Примеры 5,6 : Одновременное

использование циклического и условного операторов. Вычисление функций,

имеющих ограничения в области определения.

Примечание: Оператор IF…THEN…ELSE в QBasic должен быть записан в одну строку!

Пример 5.

CLS

REM Вычислить функцию y=1/(x^2-5*x-6)

FOR x = -10 TO 10

IF x ^ 2 — 5 * x — 6 = 0 THEN PRINT «При x=-1, x=6 функция не определена!»

ELSE y = 1 / (x ^ 2 — 5 * x — 6)

PRINT «x=»; x, » y=»; y

NEXT x

Пример 6.

CLS

REM Вычислить функцию y=1/SQR(x^2-3*x+2)

FOR x = -5 TO 5

IF x >= 1 AND x <= 2 THEN PRINT «При 1<=x=<2 функция не определена!»

ELSE y = 1 / SQR(x ^ 2 — 3 * x + 2)

PRINT «x=»; x, » y=»; y

NEXT x

Некоторые полезные команды QBasic.

Оператор LOCATE a, b — указывает

позицию экрана (a-строка, b-столбец), начиная с которой будет

печататься текст или число. Обычно используется перед оператором PRINT.

Пример: LOCATE 4, 10: PRINT «Здравствуй, мир!»

Оператор SWAP X1, X2 — заставляет переменные X1 и X2 обменяться своими значениями. Пример:

X = 3

Y = 5

SWAP X, Y

Директива FILES выдает список подкаталогов и файлов в текущем каталоге. Кроме того, выдается свободная память на жестком диске.

Директива SHELL осуществляет сеанс связи с MS-DOS. Возвращение обратно из DOS в QBasic — команда EXIT.

Кроме того, директива SHELL

«name» позволяет запускать программу name.exe или name.com, указанную в

кавычках. Эта программа должна находиться в текущем каталоге, там же,

где и *.bas файл. Расширение exe или com можно не указывать.

Графические операторы в QBasic.

1. SCREEN N — этот оператор очищает экран и задает графический режим, где N определяет тип графического режима: N=1,7,8,9,12.

При N=12 в операторе COLOR цвет

фона не задается. При N=7 режим экрана 320×200 пикселей и 16 цветов.

Режим SCREEN 7 используется весьма часто.

Если задан оператор SCREEN N, то оператор CLS можно не использовать.

2. COLOR C1, C2. COLOR — оператор, задающий цвет текста и фона, где C1 задаёт цвет текста, а C2 — цвет фона. C1, C2=0-15.

Пример использования этого оператора — COLOR 14, 1

3. Рисование точки: PSET (X,

Y), C, где X,Y — координаты точки, C — цвет точки. C=0-15. X=160, Y=100

— координаты центра экрана для режима SCREEN 7.

Пример: PSET (160, 100), 10

4. Оператор стирания точки: PRESET (X, Y)

5. Рисование линии: LINE

(X1,Y1)-(X2,Y2), C. Здесь X1,Y1 и X2, Y2 — координаты концов линии,

C-цвет. Пример: LINE (30, 100)-(120, 150), 10

6. Рисование прямоугольной рамки:

LINE (X1,Y1)-(X2,Y2), C, B.

Здесь X1,Y1 и X2,Y2-кординаты концов левой диагонали, C-цвет. Пример:

LINE (90, 110)-(140, 170), 10, B

7. Рисование закрашенного прямоугольника:

LINE (X1,Y1)-(X2,Y2), C, BF.

Здесь X1,Y1 и X2,Y2-кординаты концов левой диагонали, C-цвет. Пример:

LINE (90, 110)-(140, 170), 12, BF

8. Рисование окружности: CIRCLE (X, Y), R, C

Здесь X,Y — координаты центра, R — радиус, C — цвет.

Пример: CIRCLE (160, 110), 60, 13

9. Рисование закрашенной окружности:

CIRCLE (X, Y), R, C

PAINT (X, Y), C1, C2. Здесь

PAINT — оператор закрашивания. X,Y — координаты точки внутри

закрашиваемой области, C1 — цвет закрашивания, C2 — цвет линии границы.

Пример:

CIRCLE (160, 130), 50, 13

PAINT (160, 110), 11, 13

10. Рисование дуги и сектора: CIRCLE (X, Y), R, C, Ф1, Ф2

Здесь Ф1, Ф2 начальный и конечный углы дуги в радианах. У сектора перед Ф1 и Ф2 стоит знак минус:

CIRCLE (X, Y), R, C, -Ф1, -Ф2. Пример (pi=3.14159):

CIRCLE (160, 140), 70, 11, pi / 4, 3 * pi / 4

CIRCLE (160, 140), 60, 10, -pi / 4, -3 * pi / 4

11. Рисование эллипса: CIRCLE (X, Y), R, C, , , K

Здесь K — эксцентриситет эллипса. K<1-эллипс вытянут вдоль большой оси. K>1-эллипс вытянут вдоль малой оси.

Пример: CIRCLE (160, 100), 70, 15, , , 0.5

Пример графики на QBasic: Квадрат, три концентрические окружности и точка. Программа имеет вид:

SCREEN 7

COLOR 14, 8

PRINT «Пример графики на QBasic:»

LINE (100, 50)-(220, 150), 13, B

CIRCLE (160, 100), 20, 11

CIRCLE (160, 100), 30, 12

CIRCLE (160, 100), 40, 14

PSET (160, 100), 15

END

Установка цветов в операторе COLOR QBasic:

Число Цвет

0 Черный

1 Синий

2 Зеленый

3 Голубой

4 Красный

5 Фиолетовый

6 Коричневый

7 Серый

8 Темно-серый

9 Светло-синий

10 Светло-зеленый

11 Светло-голубой

12 Светло-красный

13 Светло-фиолетовый

14 Желтый

15 Белый

Некоторые сочетания цветов в операторе COLOR QBasic:

1) 14, 8 — желтый на темно-сером фоне;

2) 1, 7 — синий на светло-сером фоне;

3) 5, 14 — фиолетовый на желтом фоне;

4) 4, 11 — красный на голубом фоне;

5) 5, 10 — фиолетовый на светло-зеленом фоне;

6) 15, 5 — белый на фиолетовом фоне;

7) 14, 1 — желтый на синем фоне;

9) 8, 11 — темно-серый на голубом фоне;

10) 1, 15 — синий на белом фоне

Basic Input[edit | edit source]

The INPUT command is used to gather input from the user. This section will attempt to teach you how to gather input upon request from the user. For real-time input, see QBasic/Advanced Input.

Here is the syntax of the input command:

INPUT "[text to user]"; [variable] ' Question mark added

or

INPUT "[text to user]", [variable] ' No question mark added

Example:

INPUT "What is your name"; name$

or

INPUT "What is your age", age

When a semicolon (;) is used after the text output to the user, a question mark (?) and space ( ) are added to the output. When a comma (,) is used, no question mark is added.

If a string is specified (e.g., ‘name$’), anything the user enters before pressing the ‘return’ key will be accepted.

If a numeric variable (e.g., ‘age’) is specified, the user must enter a number. If any non-numeric key is entered, the error message «Redo from start» will be output and the INPUT command rerun.

6INPUT.BAS[edit | edit source]

CLS INPUT "What is your name"; name$ PRINT "Hello, "; name$; INPUT "How old are you"; age INPUT "What is your best computer game?", game$ PRINT " name:"; name$ PRINT " age:"; age; " years old" PRINT "best game:"; game$

Please note: In the PRINT command, the (;) function concatenates (joins) the contents of the string variables with the text between the quotes (» «). Note the use of spaces so that the final printed text reads properly.

If a numerical variable is specified within the PRINT command, additional space is automatically added both before and after the number.

See also: LINE INPUT command to read a line of text from a file (and place the result in a string variable) or to input a series of variables (in which case any comma found will be treated as a delimiter between fields).

INPUT # and LINE INPUT[edit | edit source]

INPUT # uses an open file stream to collect data from the file itself. The file may be a data file, a bitmap, or a text file. The syntax is:

INPUT #file_stream, variable1 ; variable2$ ' more variables can be taken.

LINE INPUT is used to collect an entire line of a text file. Syntax:

LINE INPUT 1,file_line '1 is the file stream number. Can be any other number too.

WARNING:

If input is taken beyond the file end, the error : «Input past end of file » is issued.

You can use LOF and EOF functions to prevent errors.

(LOF stands for LENGTH OF FILE while EOF stands for END OF FILE)

Text Output[edit | edit source]

Your first QBasic program: 1HELLO.BAS[edit | edit source]

The following paragraph requires a computer with QBasic installed

To begin, write down everything from the program below («PRINT «Hello World») into a text editor or into the QBasic IDE (Integrated Development Interface) itself and save it as «1HELLO.BAS». Next open the file in QBasic (unless you used QBasic IDE in which case it is already open) and press F5. Optionally you can use the «RUN» menu located on the menu bar at the top of the IDE window. This will execute (run) the program. The words «Hello World» should appear on the upper left hand side of the screen. You have just executed your first QBasic program. If you press F5 again, another line of text saying «Hello World» will appear on the upper left hand side of the screen pushing the first one down to the second row of the screen. You can follow the same procedure for the rest of the example programs in this wikibook.

1HELLO.BAS[edit | edit source]

PRINT[edit | edit source]

PRINT is QBasic’s text output function. It is the command that we will be exploring through this section. PRINT is a QBasic function that requires arguments. The argument in the «Hello, World!» program we just ran were the words «Hello, World!». So, PRINT is the function and «Hello, World!» is the argument we pass to the function.

PRINT [Text to screen]

Note: For a short cut, just use a question mark «?» in place of the command «PRINT». Likewise you can use a single quote «‘» in place of the key word REM to insert comments in your code

2HELLO.BAS[edit | edit source]

PRINT "This line will be erased" CLS PRINT "Hello"; PRINT " World", PRINT "Hello Jupiter" PRINT "Good Bye",,"For";" Now" PRINT 1,2,3,4,5

PRINT, Commas, Semicolons, tab (n) and CLS[edit | edit source]

This is what the program output should look like:

Hello World Hello Jupiter Good Bye For Now 1 2 3 4 5

The first line of 2HELLO.BAS outputs «This line will be erased.» to the screen. However, in the second line, the CLS command clears the screen immediately after. So, it will only flash momentarily. The text «Hello Jupiter» should line up with ‘2’ under it. More than one comma can be used consecutively. In this example, after «Good Bye» two commas are used to move «For Now» over two tab columns. «For Now» should line up with ‘3’.

My final statement on this topic is to play around with it. Try using commas and semicolons in a program.

3HELLO.BAS[edit | edit source]

CLS hello$ = "Hello World" number = 12 PRINT hello$, number

Variables[edit | edit source]

Variables are used to store information. They are like containers. You can put information in them and later change the information to something else. In this first example they may not seem very useful but in the next section (Input) they will become very useful.

In this example we use two types of variables: string variables and numeric variables. A string variable holds a string of characters, such as words. (A character is a letter, digit or symbol.) In this case, the characters are letters. A string variable is denoted by ending the name of the variable with a dollar sign. The string variable in this program is hello$. Whatever value you assign to hello$ will be displayed in the PRINT statement. The numeric variable is number. Numeric variables do not have a special ending like string variables.

4FACE.BAS[edit | edit source]

CLS LOCATE 14, 34 'position the left eye PRINT "<=>" 'draw the left eye LOCATE 14, 43 'position the right eye PRINT "<=>" 'draw the right eye LOCATE 16, 39 'position the nose PRINT "o|o" 'draw the nose LOCATE 18, 36 'position the mouth PRINT "\_______/" 'draw the mouth LOCATE 19, 42 'the bottom PRINT "The Face by QBasic"

LOCATE statement[edit | edit source]

LOCATE allows you to position the cursor for the next piece of text output. Contrary to Cartesian coordinates which read (X,Y), the locate statement is LOCATE Y,X. In this case Y is the distance down from the top of the screen and X is the distance from the left side of the screen. The reason that LOCATE does not follow the standard coordinate system is that it is not necessary to include the X portion; you can use the format LOCATE Y which just specifies the line to start on.

LOCATE[row, column]

LOCATE[row]

5FACE.BAS[edit | edit source]

CLS LOCATE 14, 34 COLOR 9 PRINT "<=>" LOCATE 14, 43 PRINT "<=>" COLOR 11 LOCATE 16, 39 PRINT "o|o" COLOR 4 LOCATE 18, 36 PRINT "\_______/" COLOR 20 LOCATE 19, 42 PRINT "U" LOCATE 1, 1 COLOR 16, 1 PRINT "Hello World"

COLOR statement[edit | edit source]

The program 5FACE.BAS is broken into many sections to make it easier to read. This is an example of a good programming habit. Each three-line piece of code specifies what the color, location and form of its part of the face. The order of the position and the color is unimportant. The new statement COLOR allows you to change the color of the text. Once changed, all output will be in the new color until COLOR or CLS is used.

COLOR [foreground]

COLOR [foreground], [background]

The colors are designated by numbers which will be discussed in the next section.

Color by Number[edit | edit source]

There are 16 colors (in screen mode 0), numbered from 0 to 15.

| 0 | Black | 8 | Gray |

| 1 | Blue | 9 | Light Blue |

| 2 | Green | 10 | Light Green |

| 3 | Cyan | 11 | Light Cyan |

| 4 | Red | 12 | Light Red |

| 5 | Purple | 13 | Light Purple |

| 6 | Brown/Orange | 14 | Yellow (Light Orange) |

| 7 | Light Grey (White) | 15 | White (Light White) |

If you look carefully at this chart you can see that there are 8 main colors (0 through 7) and then those colors repeat, each in a lighter shade. You may also notice that the colors act as a combination of binary values (where blue=1, green=2, red=4, etc.) This makes it much easier to memorize the color scheme. Blinking colors are also available: at 16, the colors start over again with blinking black and extend through 31 (blinking white). However, the blinking option is not available for the background, only for the text (foreground). Add 16 to the color you wish to blink. e.g.: 2+16=18 — Blinking Green, 4+16=20 — Blinking Red.

It is possible to switch the blinking foreground text with an intense background, but this task is beyond the scope of this QBasic textbook, and may not work when MS Windows displays the console in a windowed mode.

Font[edit | edit source]

On a VGA compatible video card, you can inspect and change the font used in screen mode 0.

OUT &H3CE, 5: OUT &H3CF, 0 'Clear even/odd mode OUT &H3CE, 6: OUT &H3CF, 4 'Map VGA mem A0000-BFFFF OUT &H3C4, 2: OUT &H3C5, 4 'Set bit plane 2 OUT &H3C4, 4: OUT &H3C5, 6 'Clear even/odd mode again

You can now use PEEK and POKE to access the character data. It starts at absolute address &HA0000 and every character is 32 bytes, each of which is a row of eight bits. The highest bit of each byte corresponds to the leftmost pixel of each row. Usually only the first 16 or 8 rows are used, depending on the WIDTH setting.

When you’re done, it’s important to put the memory mapping back to what QBasic expects:

OUT &H3CE, 6: OUT &H3CF, 14 'Map VGA mem B8000-BFFFF

Summary[edit | edit source]

In this section we looked at several methods to manipulate text output. All centered around the PRINT statement. LOCATE and COLOR modified where the text was displayed and how it looked. We used CLS to clear the screen and gave a brief introduction to variables which will be expanded upon in later sections.

Basic Math[edit | edit source]

There are six numerical variables within QBasic:

| Type | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|

| Integer | -32,768 | 32,767 |

| Long Integer | -2,147,483,648 | 2,147,483,647 |

| Float | -3.37×10^38 | 3.37×10^38 |

| Double | -1.67×10^308 | 1.67×10^308 |

| 64-bit Integer | -9,223,372,036,854,775,808 | 9,223,372,036,854,775,807 |

| 64-bit Float | ±1.18E−4932 | ±1.18E+4932 |

Please note that Integer and Float type variables for 64-bit are available only in QB64.

A lot of programming is math. Don’t let this scare you: a lot of the math is simple, but it’s still math. In this section, we will look at doing some basic math (the same stuff you learned in the 3rd grade) and manipulating numbers.

Equation Setup[edit | edit source]

In QBasic an equation has a basic setup a right side and a left side. For instance X=5, as you can probably figure out, this sets the variable X to 5. But we can use variables on the right side too. Y=X*10 would set Y equal to 10 times X, in this situation, 50. In this next program I will show several equations to give you a feel for math.

7MATH.BAS[edit | edit source]

CLS 'Set a-d to initial values a = 10 b = 6 c = 3.1415 d = 3.333333 e = a + b PRINT a; "+"; b; "="; e f = c * d PRINT c; "x"; d; "="; f g = b - c PRINT b; "-"; c; "="; g h = b / d PRINT b; "/"; d; "="; h i = INT(d) PRINT "Remove the decimal from "; d; "="; i

Understanding 7MATH.BAS[edit | edit source]

The most important thing you can take away from this is the setup for math equations. I think you can figure out what all the symbols are and what they do, but QBasic is picky about equations. For ‘e=a+b’, if you try ‘a+b=e’ it will not work.

The final thing I would like to address in 7MATH.BAS is the INT() function. As far as vocabulary, a function is something that takes in a piece of information and gives you another piece of information back. So PRINT, was a statement, and INT() is a function. The INT() function takes a number and truncates its decimal, it does not round. So INT(5.1) is 5 and INT(5.999) is still 5. If you want to round a number use CINT().

8MATH.BAS[edit | edit source]

CLS INPUT "Enter a number: ", x PRINT x = x + 5 PRINT "X is now: "; x x = x * x PRINT "X is now: "; x x = x / 5 PRINT "X is now: "; x x = x - 4 PRINT "X is now: "; x x = x / x PRINT "X should be 1: "; x

Understanding 8MATH.BAS[edit | edit source]

8MATH.BAS shows one simple concept that is very important in programming, but impossible in math. The way that the computer calculates the equation is it does all the math on the right side of the equation and then sticks it in the variable on the left side. So the equation x=x+5 makes perfect sense, unlike math where it is a contradiction. Reassigning a value to a variable based on its current value is common and a good way to keep the number of variables down.

9TIP.BAS[edit | edit source]

CLS INPUT "How much is your bill: ", bill INPUT "What percent tip do you want to give: ", tip tip = tip / 100 'change percent to decimal tip = tip * bill 'change decimal to money PRINT PRINT "The tip is"; tip; "$." PRINT "Pay"; tip + bill; "$ total."

Tip Calculator[edit | edit source]

9TIP.BAS calculates your tip and total bill from the bill and percent tip you wish to give. The first three lines clear the screen and get the information from the user. The fifth line changes the tip from a percent to the correct decimal by dividing by 100 (ex. 20%=.2 because 20/100=.2) the next line takes that percent and turns it into a dollar value by multiplying the decimal value by the bill. So if your bill is $20.00 and you leave a 20% tip, it multiplies 20*.2 which is 4 or $4.00. The last three lines format the output.

This is a good example of a complete program. It collects information from the user, it processes the information and it gives the user feedback. Also, the middle section of the program is a good example of variable conservation. This is subject that will take some practice to get used to. In writing a program, if you use too many variables, it will become difficult to keep track of all of them. If you try and conserve too much, you code may become difficult to understand.

You may notice that the program may print more than two decimal places if you enter a bill that is not an exact dollar value. As an exercise, try modifying the program so that it only displays two decimal places — you can use the CINT() function or any other rounding method you intend to use.

10OROP.BAS[edit | edit source]

'ORder of OPerations CLS a = 15 b = 10 c = 12.2 d = 1.618 PRINT a * b + c 'these two are different PRINT a * (b + c) PRINT PRINT b - c / d 'these two are different PRINT (b - c) / d PRINT PRINT a * b - c * d / a + d 'these two are the same PRINT (a * b) - ((c * d) / a) + d

Parentheses and Order of Operations[edit | edit source]

10OROP.BAS is an example of order of operations and how parentheses can be used to manipulate it. I do not want to go into an indepth explanation of the order of operations here. The best advice I can give is unless you are sure of the order of operations, use parentheses to make sure the equation works how you want. All you need to know about parentheses is that the deepest nested parentheses calculate first. If you wish to know more, there are plenty of algebra resources available. On that note, you may wish to brush up on algebra. While it is not necessary for programming, it can help make programming easier and it can allow you to create more advanced programs.

Random Numbers[edit | edit source]