RT is an autonomous non-profit organization.

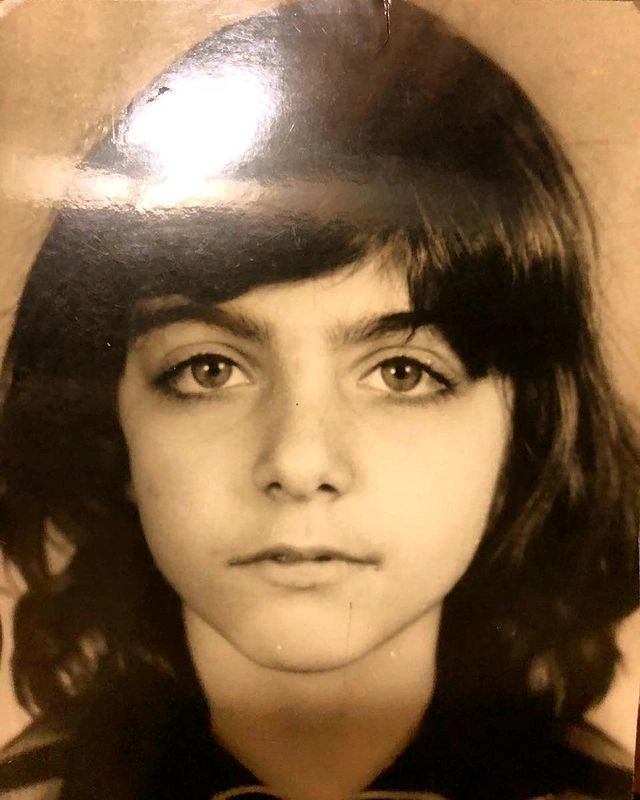

Margarita Simonyan

Editor-in-Chief of RT

In 2005, Margarita Simonyan launched RT, Russia’s first round-the-clock, English-language, international TV news channel, which has since expanded to a global news network with platforms in seven languages, and sister news agency RUPTLY.

In 2017, Margarita Simonyan was included in the prestigious Forbes list of the world’s most powerful women, a dozen spots higher than the former US Secretary of State and ex-Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Clinton.

Under Margarita’s helm, RT grew its TV audience to 100 million weekly viewers and became the first TV news network in the world to hit ten billion views across its channels on YouTube, as well as an eleven-time Emmy finalist.

In 2013, Margarita Simonyan also became Editor-in-chief of Rossiya Segodnya, an international media group that includes news agency and radio Sputnik, which broadcasts in more than 30 languages. Margarita began her journalism career in the Russian city of Krasnodar at the local TV and radio station, eventually heading up a regional bureau for Russia’s largest nation-wide broadcaster, VGTRK.

As a war correspondent, she reported from Chechnya during the Second Chechen War, from the Beslan School Siege, and from Abkhazia, which earned her several journalism awards.

Alexey Nikolov

Managing Director of RT

Alexey’s journalistic pursuits began in the early 1970s, when at just 13 years of age he published his first article. In the Soviet era, his career focused predominantly on sports journalism, which was largely devoid of political interference, and Alexey has reported on major sporting events, including the Olympics. During the Perestroika, Alexey began to cover general issues and in 1990 joined Russia’s first ever independent radio station Echo of Moscow, where he soon became a news anchor and a reporter. For this station he covered some of the most important events of the 90s in Russia, including the August Coup of 1991, the October 1993 Constitutional Crisis.

Since 1994 Alexey has mostly worked on Russian television. He was instrumental in launching the new national network, REN TV. At the same time he continued his love affair with sports journalism and still writes frequently on the subject for national newspapers and magazines. He also became Russia’s first golf commentator and occasionally serves in this capacity at Eurosport and Sport TV channels. Alexey is a winner of the prestigious Russian Union of Journalists’ award “For Professional Excellence” and several other industry awards. He is also a professor of Journalism at Sholokhov Moscow State University for the Humanities.

Alexey joined Russia Today (now RT) in 2005 and is now the Managing Director for the entire organization.

Alexey was elected Chair of the Executive Committee of the Association for International Broadcasting in March 2016. In 2017, he was appointed Deputy Head of the Department of Media at the Higher School of Economics.

Дмитрий Константинович Киселев

Генеральный директор медиагруппы «Россия сегодня».

Окончил отделение скандинавской филологии филологического факультета Ленинградского государственного университета им. А.А. Жданова.

Начал работать в 1975 году в Агентстве печати «Новости». С 1978 года работал на иновещании Гостелерадио СССР в норвежской и польской редакциях, а также Всемирной службе на английском языке, затем – ведущим и комментатором программы «Время», Телевизионной службы новостей (ТСН), ведущим программ «Час Пик» и «Окно в Европу» на ОРТ.

С мая 1991 года Дмитрий Киселев сотрудничал с Первым немецким телевидением ARD, крупнейшим немецким частным каналом RTL, японской телекомпанией NHK. В 1992-1995 годах возглавлял региональное бюро телекомпании «Останкино» в странах Северной Европы и Бенилюкса.

С 1995 года работал на телеканале REN-TV, был автором и ведущим программы «Национальный интерес». В 1999-2000 годах — автор и ведущий программы «В центре событий» на ТВЦ. С 2000 года — главный редактор информационной службы телеканала ICTV (Украина), автор и ведущий программ «Свобода слова» и ежедневной информационно-аналитической программы «Подробно с Дмитрием Киселевым».

С 2003 года Дмитрий Киселев начал работать на канале «Россия» Российской государственной телерадиокомпании, где открыл новую программу «Утренний разговор с Дмитрием Киселевым» а также вел программы «Парламентский час», «Вести», «Национальный интерес», «Исторический процесс». С 2008 по 2012 год занимал должность заместителя Генерального директора Всероссийской государственной телевизионной и радиовещательной компании (ВГТРК). С сентября 2012 года по настоящее время – автор и ведущий программы «Вести недели» на телеканале «Россия 1».

9 декабря 2013 года Указом Президента РФ назначен генеральным директором федерального государственного унитарного предприятия «Международное информационное агентство “Россия сегодня”». Сегодня «Россия сегодня» — международная медиагруппа, которая объединяет более десяти СМИ, лидеров в своих областях.

Дмитрий Киселев является основателем джазового фестиваля Koktebel Jazz Party. Фестиваль, который проходит ежегодно с 2003 года, стал одним из самых ярких событий в культурной жизни Крыма. По его инициативе был запущен ряд значимых социальных проектов, в том числе акция «Пожалуйста, дышите!», посвященная работе врачей в период пандемии COVID-19.

Награжден Орденом Дружбы, Орденом «За заслуги перед Отечеством» IV степени, Орденом преподобного Сергия Радонежского II степени, Орденом Почета, медалью «За возвращение Крыма», знаком отличия «За заслуги перед Москвой». Лауреат высших телевизионных премий России и Украины: ТЭФИ и «Телетриумф».

«ANO TV-Novosti» redirects here. Not to be confused with RIA Novosti.

«RTTV» redirects here. Not to be confused with RTVI.

|

|

| Type | State media,[1] news channel, propaganda[2] |

|---|---|

| Country | Russia |

| Broadcast area | Worldwide |

| Headquarters | Moscow |

| Programming | |

| Language(s) | News channel: English, French, Arabic & Spanish Documentary channel: English, French, Russian Online platforms: German[3] |

| Picture format | 1080i (HDTV) (downscaled to 16:9 480i/576i for the SDTV feed) |

| Ownership | |

| Owner | ANO «TV-Novosti»[4] |

| Sister channels |

|

| History | |

| Launched | 10 December 2005; 17 years ago (registered on 6 April 2005)[8] |

| Former names | Russia Today (2005–2009) |

| Links | |

| Website | www |

RT (formerly Russia Today or Rossiya Segodnya) (Russian: Россия Сегодня)[9] is a Russian state-controlled[1] international news television network funded by the Russian government.[16][17] It operates pay television and free-to-air channels directed to audiences outside of Russia, as well as providing Internet content in Russian, English, Spanish, French, German and Arabic.

RT is a brand of TV-Novosti, an autonomous non-profit organization founded by the Russian state-owned news agency RIA Novosti in April 2005.[8][18] During the economic crisis in December 2008, the Russian government, headed by Prime Minister Vladimir Putin, included ANO «TV-Novosti» on its list of core organizations of strategic importance to Russia.[19][20][21] RT operates as a multilingual service with channels in five languages: the original English-language channel was launched in 2005, the Arabic-language channel in 2007, Spanish in 2009, German in 2014 and French in 2017. RT America (2010–2022),[22][23] RT UK (2014–2022) and other regional channels also produce local content. RT is the parent company of the Ruptly video agency,[5] which owns the Redfish video channel and the Maffick digital media company.[6][7]

RT has regularly been described as a major propaganda outlet for the Russian government and its foreign policy.[2] Academics, fact-checkers, and news reporters (including some current and former RT reporters) have identified RT as a purveyor of disinformation[58] and conspiracy theories.[65] UK media regulator Ofcom has repeatedly found RT to have breached its rules on impartiality, including multiple instances in which RT broadcast «materially misleading» content.[72]

In 2012, RT’s editor-in-chief Margarita Simonyan compared the channel to the Russian Ministry of Defence.[73] Referring to the Russo-Georgian War, she stated that it was «waging an information war, and with the entire Western world».[17][74] In September 2017, RT America was ordered to register as a foreign agent with the United States Department of Justice under the Foreign Agents Registration Act.[75]

RT was banned in Ukraine in 2014 after Russia’s annexation of Crimea;[76] Latvia and Lithuania implemented similar bans in 2020.[77][78] Germany banned RT DE in February 2022.[79] During the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the European Union and Canada formally banned RT and independent service providers in over 10 countries suspended broadcasts of RT.[80][81][82] Social media websites followed by blocking external links to RT’s website and restricting access to RT’s content.[83][84] Microsoft removed RT from their app store and de-ranked their search results on Bing,[85][86] while Apple removed the RT app from all countries except for Russia.[87]

History

Foundation

RT’s formation was part of a public relations effort by the Russian Government in 2005 to improve Russia’s image abroad.[88] RT was conceived by former media minister Mikhail Lesin[89] and Aleksei Gromov.[90] At the time of RT’s founding, RIA Novosti director Svetlana Mironyuk stated: «Unfortunately, at the level of mass consciousness in the West, Russia is associated with three words: communism, snow and poverty», and added «we would like to present a more complete picture of life in our country».[89] RT is funded by the Federal Agency for Press and Mass Media, part of the government of Russia.[91][92]

In 2005, RIA Novosti founded ANO TV-Novosti (or «Autonomous Non-profit Organization TV-News») to serve as the parent organization for RT. ANO TV-Novosti was registered on 6 April 2005,[8] and Sergey Frolov (Сергей Фролов) was appointed its CEO.[93]

The channel was launched as Russia Today on 10 December 2005. At its launch, the channel employed 300 journalists, including approximately 70 from outside Russia.[88] Russia Today appointed Margarita Simonyan as its editor-in-chief; she recruited foreign journalists as presenters and consultants.[89]

Simonyan, aged 25 years old when she was appointed, was a former Kremlin pool reporter who had worked in journalism since she was 18. She told The New York Times that after the fall of the Soviet Union, many new young journalists were hired, resulting in a much younger pool of staffers than other news organizations.[94] Journalist Danny Schechter (who has appeared as a guest on RT)[95] stated that, having been part of the launch staff at CNN, he saw RT as another «channel of young people who are inexperienced, but very enthusiastic about what they are doing».[96] Shortly after the channel was launched, James Painter wrote that RT and similar news channels such as France 24 and TeleSUR saw themselves as «counter-hegemonic», offering a differing vision and news content from that of Western media like CNN and the BBC.[97]

Development and expansion

RT launched several new channels in ensuing years: the Arabic language channel Rusiya Al-Yaum in 2007, the Spanish language channel RT Actualidad in 2009, RT America – which focuses on the United States – in 2010, and the RT Documentary channel in 2011.[22]

In August 2007, Russia Today became the first television channel to report live from the North Pole (with the report lasting five minutes and 41 seconds). An RT crew participated in the Arktika 2007 Russian polar expedition, led by Artur Chilingarov on the Akademik Fyodorov icebreaker.[98][99] On 31 December 2007, RT’s broadcasts of New Year’s Eve celebrations in Moscow and Saint Petersburg were broadcast in the hours prior to the New Year’s Eve event at New York City’s Times Square.[99]

Russia Today drew particular attention worldwide for its coverage of the 2008 South Ossetia war.[99][100][101] RT named Georgia as the aggressor[101] against the separatist governments of South Ossetia and Abkhazia, which were protected by Russian troops.[102] RT saw this as the incident that showcased its newsgathering abilities to the world.[43] Margarita Simonyan stated: «we were the only ones among the English-language media who were giving the other side of the story – the South Ossetian side of the story».[100]

In 2009, Russia Today was rebranded to «RT», which George Washington University academics Jack Nassetta and Kimberly Gross described as an «[attempt] to shed state affiliation».[15] Simonyan said the company had not changed names but the company’s corporate logo was changed to attract more viewers: «who is interested in watching news from Russia all day long?»[22]

Julia Ioffe also describes 2009, when the Barack Obama administration came to office «promising a different approach toward Russia», as a time when RT became «more international and less anti-American», and «built a state-of-the-art studio and newsroom» in the U.S. capital[43]

In early 2010, RT unveiled an advertising campaign to promote its new «Question More» slogan.[103] The campaign was created by Ketchum, GPlus, and London’s Portland PR.[45] One of the advertisements featured as part of the campaign showed U.S. President Barack Obama morphing into Iranian leader Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and asked: «Who poses the greatest nuclear threat?» The ad was banned in American airports. Another showed a Western soldier «merging» with a Taliban fighter and asked: «Is terror only inflicted by terrorists?»[104] One of RT’s 2010 billboard advertisements won the British Awards for National Newspaper Advertising «Ad of the Month».[105]

In 2010, Walter Isaacson, Chairman of the U.S. Government’s Broadcasting Board of Governors, which runs Voice of America, Radio Free Europe and Radio Free Asia, called for more money to invest in the programs because «We can’t allow ourselves to be out-communicated by our enemies», specifically mentioning Russia Today, Iran’s Press TV and China’s China Central Television (CCTV) in the following sentence. He later explained that he actually was referring to «enemies» in Afghanistan, not the countries he mentioned.[106] In 2011, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton stated that the U.S. was «losing the information war» abroad to foreign channels like RT, Al Jazeera and China Central Television[107] and that they were supplanting the Voice of America.[108][109]

2012–2021

In early 2012, shortly after his appointment as U.S. Ambassador to Russia, Michael McFaul challenged Margarita Simonyan[110] on Twitter about allegations from RT[111] that he had sent Russian opposition figure Alexei Navalny to study at Yale University.[110][111] According to RT, McFaul was referring to a comment in an article by political scientist Igor Panarin, which RT had specified were the views of the author.[112][113] McFaul then accepted an interview by Sophie Shevardnadze on RT on this and other issues and reasserted that the Obama administration wanted a «reset» in relations with Russia.[114][115]

On 17 April 2012, RT debuted World Tomorrow, a news interview programme hosted by WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange. The first guest on the program was Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah.[116][117][118] The interview made global headlines as Nasrallah rarely gives interviews to Western media.[119] Commentators described this as a «coup».[120][121] WikiLeaks described the show as «a series of in-depth conversations with key political players, thinkers and revolutionaries from around the world».[122] It stated that the show is «independently produced and Assange has control»; WikiLeaks offers a «Broadcasters license, only».[123]

Assange said that RT allowed his guests to discuss things that they «could not say on a mainstream TV network».[124] Assange’s production company made the show and Assange had full editorial control. Assange said that, if Wikileaks had published large amounts of compromising data on Russia, his relationship with RT might not have been so comfortable.[119] In August of that year, RT suffered a denial of service attack. Some people linked the attack to RT’s connection with Assange, and others to an impending court verdict related to Pussy Riot.[125]

On 23 October 2012, RT, along with Al Jazeera and C-SPAN, broadcast the Free and Equal Elections Foundation third-party debate among four third-party candidates for President of the United States.[126][127] On 5 November, RT broadcast the two candidates that were voted winners of that debate, Libertarian Party candidate Governor Gary Johnson and Green Party candidate Jill Stein, from RT’s Washington, D.C. studio.[128][129][130]

In May 2013, RT announced that former CNN host Larry King would host a new talk show on RT. King said in an advertisement on RT: «I would rather ask questions to people in positions of power, instead of speaking on their behalf.»[131][132] As part of the deal, King would also bring his Hulu series Larry King Now to RT. On 13 June 2013, RT aired a preview telecast of King’s new Thursday evening program Politicking, with the episode discussing Edward Snowden’s leaking of the PRISM surveillance program.[133]

Vladimir Putin visited the new RT broadcasting centre in June 2013 and stated:

«When we designed this project back in 2005 we intended introducing another strong player on the international scene, a player that wouldn’t just provide an unbiased coverage of the events in Russia but also try, let me stress, I mean – try to break the Anglo-Saxon monopoly on the global information streams. … We wanted to bring an absolutely independent news channel to the news arena. Certainly the channel is funded by the government, so it cannot help but reflect the Russian government’s official position on the events in our country and in the rest of the world one way or another. But I’d like to underline again that we never intended this channel, RT, as any kind of apologetics for the Russian political line, whether domestic or foreign.»[134][16]

In early October 2014, RT announced the launch of a dedicated news channel, RT UK, aimed at British audiences. The new channel began operating on 30 October 2014.[135]

In October 2016, the NatWest bank stated that they will no longer provide banking services to RT in the UK without providing any reasons. This decision was criticised by Margarita Simonyan, the editor-in-chief of RT, and the Russia Government. Simonyan sarcastically tweeted that: «Long live freedom of speech!»[136] However, NatWest reversed its decision in January 2017, said it had reached a resolution with RT. Simonyan said the decision showed that «common sense has prevailed».[137]

In 2018, some of the RT staff started a new media project, Redfish.media, that positioned itself as «grassroots journalism».[138][6] The website was criticized by activist Musa Okwonga for deceptively interviewing him and then distributing it across RT channels while hiding its real affiliation.[139] Another similar RT project is In the NOW, started in 2018.[140] On 15 February 2019, Facebook temporarily blocked the In the NOW page, saying that even though it does not require pages to disclose who funds them, it had suspended the page so viewers would not «be misled about who’s behind them». Anissa Naouai, CEO of Maffick, which published the page, described the blocking as «unprecedented discrimination», and said that Facebook did not ask other channels to declare their parent company and financial affiliations. As of February 2019, a majority of Maffick stock was controlled by Ruptly, an RT subsidiary, with Naouai owning the remaining 49%. Facebook unblocked the page on 25 February 2019; Naouai said the company had agreed to do so once the page was updated to feature information on In the NOW‘s funding and management. She added that this requirement has been applied to no other Facebook page. In the NOW also has an active channel on YouTube and regularly posts videos from Soapbox, a Maffick-owned channel.[141][142][7][143]

In February 2021, Matt Field from the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists reported that RT had created an account on Gab, a social network known for its far-right userbase, right before the start of former U.S. President Donald Trump’s second impeachment trial.[144] Field commented that RT had posted several articles on its Gab account, including one criticizing The Lincoln Project, an organization run by anti-Trump Republicans.[144]

In December 2021 RT launched a TV channel in Germany, RT DE TV using a license for cable and satellite broadcasting issued in Serbia. A week after the launch, on 22 December the channel was removed from broadcasting via European satellites by the European satellite operator at the request of the German media regulator.[145]

2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine

On 27 February 2022, the president of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen announced the European Union would ban RT and Sputnik (plus their subsidiaries) from operating in its 27 member countries.[146] The ban resulted in RT being blocked on downstream television networks located outside EU, such as the United Kingdom and Singapore as they were dependent on EU companies for the signal feed to RT.[147][148] Canadian telecom companies Shaw, Rogers, Bell and Telus announced they would no longer offer RT in their channel lineups (although Rogers replaced its RT broadcasts with a Ukrainian flag).[149] This move was praised by Canada’s Minister of Canadian Heritage Pablo Rodriguez who called the network the «propaganda arm» of Vladimir Putin.[150] On 28 February, Ofcom announced they had opened 15 expedited investigations into RT.[151] These investigations will be focused on the 15 news editions broadcast on 27 February between 05:00 and 19:00 and will check if the coverage broke impartiality requirements in the broadcast code.[152] On 2 March, the regulation was published which meant the ban was in force.[153]

Facebook, Instagram, and TikTok made RT’s and Sputnik’s social media content unavailable to users in the European Union on 28 February.[154][155] Microsoft removed RT and Sputnik from MSN, the Microsoft Store, and the Microsoft Advertising network on the same day.[156] YouTube, on 1 March, banned access to all RT and Sputnik channels on its platform in Europe (including Britain).[a][83][157] Apple followed by removing RT and Sputnik from its App Store in all countries except Russia.[158] Roku dropped the RT app from its channel store,[159] while DirecTV pulled RT America from its channel lineup.[160] On March 1, the National Administration of Telecommunications of Uruguay announced the removal of RT from the Antel TV streaming platform.[161] New Zealand satellite television provider Sky also removed RT, citing complaints from customers and consultation with the Broadcasting Standards Authority.[162] Reddit blocked new outgoing links to RT and Sputnik on 3 March.[163] On 11 March, YouTube blocked RT and Sputnik worldwide.[164] From March 16, the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission officially banned RT and RT France from the list of non-Canadian programming services authorized for distribution.[80]

On 8 March 2022, RT France challenged the EU ban of its activities in the General Court of the Court of Justice of the European Union.[165] After refusing to «urgently» consider the case on 30 March,[166] the General Court dismissed the case on 27 July 2022, ruling that the ban against RT was justified.[167]

Between 22 and 26 February 2022, a couple of days before and after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, «posts on Facebook from RT and Sputnik got more than 5 million likes, shares and comments». On YouTube, videos of «false stories, claiming that Ukrainians had attacked Russians or describing a ‘genocide’ against Russian-speaking Ukrainians in the separatist Donbas region,» were watched «73 million times.»[168] During the invasion, hacktivist collective Anonymous launched a distributed denial of service attack that temporarily disabled the websites of RT and other Russian government-controlled organizations.[169][170] In March 2022, RT America closed and most of its staff ceased to work for the outlet.[23] RT began selling merchandise emblazoned with the «Z» military symbol – a pro-Kremlin and pro-war emblem – a few days after the start of the invasion.[171]

In March 2022, Vice News reported that RT had established a channel on Gab’s video sharing platform Gab TV, which describes itself as a «free speech broadcasting platform.» Vice News observed that Gab CEO Andrew Torba had given his support for Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and Torba publicly supported RT, claiming that they are being subject to the same censorship as American conservatives «by Big Tech and the globalist regime». Torba also falsely claimed that Gab is «the one place on the internet where you can find RT News» when RT also has a presence on video sharing platform Rumble.[172] Not all branches of RT have suffered declines since the war started. Interactions with the Arabic-language Facebook page «RT Online» grew 161.2% from Feb. 28 to mid-March, «RT Play in Español» went up a 22.5%.[168]

In October 2022, RT presenter Anton Krasovsky said on air that Ukrainian children who had in the past criticised the Soviet Union as occupiers of Ukraine should have been drowned or burned; he additionally laughed at reporting that Russian soldiers raped elderly Ukrainian women during the 2022 invasion.[173] He was subsequently suspended by Simonyan, and criminal case investigation was opened.[174]

In September and October 2022, RT launched RT Hindi[175] and RT Balkan,[176][177] to expand its audience.

Organization

State-owned RIA Novosti news agency, which founded RT in 2005, is one of the largest in Russia. Its former chairperson was Svetlana Mironyuk, who modernised the agency after being appointed in 2003.[178][179][180]

In 2007, RT established offices in the same building as RIA Novosti, after the Russian Union of Journalists was forced to vacate them.[181] In 2012, Anna Kachkayeva, Dean of Media Communications at Moscow’s Higher School of Economics, stated that the two organizations «share the same roof» because they are located in the same building, but in «funding, editorial policy, management and staff, they are two independent organisations whose daily operations are not interconnected in any way».[182] In 2008, Simonyan noted that more than 50 young RT journalists had gone on to take positions in large Western media outlets.[99] By 2010, RT’s staff had grown to 2,000.[22]

In December 2012, RT moved its production studios and headquarters to a new facility in Moscow. The move coincided with RT’s upgrade of all of its English-language news programming to high-definition.[183][184][185]

In 2013, a presidential decree issued by Vladimir Putin dissolved RIA Novosti, replacing it with a new information agency called Rossiya Segodnya (directly translated as Russia Today).[186] On 31 December 2013, Margarita Simonyan, editor-in-chief of the RT news channel, was also appointed editor-in-chief of the new news agency while maintaining her duties for the television network.[187]

From 18 August 2020 to 18 August 2021, ANO TV Novosti was owned by the federal state unitary enterprise RAMI RIA Novosti (Russian: ФГУП «РАМИ «РИА Новости») and the Association for the Development of International Journalism (ADIJ; Russian: Ассоциация развития международной журналистики (АРМЖ)), which was founded by Margarita Simonyan and few other RT associates. On 18 August 2021, RAMI RIA Novosti was liquidated and the ownership of ANO TV Novosti was transferred to ADIJ.[188][189][190]

Budget

When it was established in 2005, ANO TV-Novosti invested $30 million in start-up costs to establish RT,[191] with a budget of $30 million for its first year of operation. Half of the network’s budget came from the Russian government; the other half came from pro-Kremlin commercial banks at the government’s request.[97] Its annual budget increased from approximately $80 million in 2007 to $380 million in 2011, but was reduced to $300 million in 2012.[192][1][193] President Putin prohibited the reduction of funding for RT on 30 October 2012.[194]

About 80 percent of RT’s costs are incurred outside Russia, paying partner networks around $260 million for the distribution of its channels in 2014.[40][195] In 2014, RT received 11.87 billion rubles ($310 million) in government funding and was expected to receive 15.38 billion rubles ($400 million) in 2015.[196] (For comparison, the bigger BBC World Service Group had a $376 million budget in 2014–15.)[197] At the start of 2015, as the ruble’s value plummeted and a ten percent reduction in media subsidies was imposed, it was thought that RT’s budget for the year would fall to about $236 million.[40][195] Instead, government funding was increased to 20.8 billion rubles (around $300 million) in September.[198] In 2015, RT was expected to receive 19 billion rubles ($307 million) from the Russian government the following year.[199] As of 2022, RT is the leader in terms of state funding among all Russian media. Between 2022 and 2024, RT will receive 82 billion rubles.[200][201]

Network

According to RT as of March 2022, the network’s feed is carried by 22 satellites and over 230 operators, providing a distribution reach to about 700 million households in more than 100 countries.[202] RT also stated that RT America was available to 85 million households throughout the United States, as of 2012.[203]

In addition to its main English language channel RT International, RT UK and RT America, RT also runs Arabic-language channel Rusiya Al-Yaum, Spanish language channel Actualidad RT, as well as the RTDoc documentary channel. RT maintains 21 bureaus in 16 countries, including those in Washington, D.C., New York City; London, England; Paris, France; Delhi, India; Cairo, Egypt and Baghdad, Iraq.[3]

| Channel | Description | Language | Launched |

|---|---|---|---|

| RT International | RT’s main news channel, covering international and regional news from a Russian perspective. It also includes commentary and documentary programs. Based in Moscow with a presence in Washington, New York, London, Paris, Delhi, Cairo and Baghdad and other cities.[3] | English | 2005 |

| RT Arabic | Based in Moscow and broadcast 24/7. Programmes include news, feature programming and documentaries.[204] | Arabic | 2007 |

| RT Spanish | Based in Moscow with bureaus in Miami, Los Angeles, Havana and Buenos Aires. Covers headline news, politics, sports and broadcast specials.[205] | Spanish | 2009 |

| RT America | RT America was based in RT’s Washington, D.C. bureau, it included programs hosted by American journalists. The channel maintained a separate schedule of programs each weekday from 4:00 p.m. to 12:00 a.m. Eastern Time, and simulcasted RT International at all other times. RT America was compelled to register as a foreign agent with the United States Department of Justice National Security Division under the Foreign Agents Registration Act.[206] | English | 2010 (closed 3 March 2022) |

| RT UK | RT UK was based at RT’s London bureau at Millbank Tower. Includes programs hosted by British journalists. The channel offered five hours of programming per day, Monday to Thursday UK News at 6 pm, 7pm, 8pm, 9pm and 10 pm and simulcasted RT International at all other times. On Fridays there was no 10 pm UK News bulletin.[207] | English | 2014 (closed 2 March 2022) |

| RT Documentary | A 24-hour documentary channel. The bulk of its programming consists of RT-produced documentaries related to Russia.[208] | English, Russian | 2011 |

The sharp decline in the ruble at the end of 2014 forced RT to postpone German- and French-language channels.[197]

In addition to news agency Ruptly, RT also operates the following websites: RT на русском (in Russian),[209] RT en français (French),[210] RT DE (German).[211]

In 2015, RT’s YouTube news channels were: RT (the main channel), RT America, RT Arabic, RT en Español, RT Deutsch, RT French, RT UK, RT на русском and the newly launched RT Chinese.[40]

The German service (RT DE) was removed from YouTube in September 2021 for breaking the websites rules on COVID misinformation.[212] As noted by Russian journalists, Russian RT edition «aggressively» promoted COVID-19 vaccination in Russia, resorting to calling anti-vaccination activists «imbeciles», while at the same time foreign RT channels are promoting the same anti-vaccination misinformation that it criticizes in Russia.[213][214]

In September 2012, RT signed a contract with Israeli-based RRSat to distribute high-definition feeds of the channel in the United States, Latin America and Asia.[215] In October 2012, RT’s Rusiya Al-Yaum and RT joined the high-definition network Al Yah Satellite Communications («YahLive»).[216] On 12 July 2014, during his visit to Argentina, Putin announced that Actualidad RT would broadcast free-to-air in the country, the first foreign television channel to do so there.[217][218] According to Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, Argentina’s State Media Authorities decided to suspend RT on 11 June 2016, along with Venezuelan television channel TeleSur, which had both been authorized by the previous left-leaning government of Cristina Kirchner. Officially, Argentina wanted to devote RT’s frequency to domestic broadcasts.[219] RT was made available on the dominant Australian subscription television platform Foxtel on 17 February 2015.[220]

Ratings/impact

- Audience ratings

The RT website (as of March 2022), maintains that «since June 2012», RT has «consistently and significantly outperforms other foreign channels including Euronews and Fox News. RT’s quarterly audience in the UK is 2.5 million viewers».[221] However, according to The Daily Beast, citing leaked documents from «Vasily Gatov, a former RIA Novosti employee» (as of 2015) RT “hugely exaggerates its viewership,”;[222] and its most-watched segments were on apolitical subjects.[223] Between 2013 and 2015, over 80% of RT’s viewership was for videos of accidents, crime, disasters, and natural phenomena, such as the 2013 Chelyabinsk meteor event, with less than 1% of viewership for political videos.[224] In late 2015, all of the 20 most-watched videos on its main channel, totaling 300 million views, were described as «disaster/novelty». Of the top 100, only a small number could be categorized as political, with only one covering Ukraine.[198] The most popular video of Russian president Putin shows him singing «Blueberry Hill» at a 2010 St. Petersburg charity event.[224] In 2017, The Washington Post analysed RT’s popularity and concluded that «it’s not very good at its job» as «Moscow’s propaganda arm» due to its relative unpopularity.[225] RT has disputed both The Daily Beast and The Washington Post assessments, saying their analyses used outdated viewership data.[226][227]

A study by Professor Robert Orttung at George Washington University stated that RT uses human interest stories without ideological content to attract viewers to its channels. Between January and May 2015, the Russian-language channel had the most viewers, with approximately double the number of the main channel, despite only having around one-third the number of subscribers.[40]

According to data compiled by Oxford’s Rasmus Kleis Nielsen prior to the invasion of Ukraine, RT’s «online reach in the U.K., France, and Germany» was «not great on the web, but surprisingly strong on social media, at least in spots».[222] For example, in Germany, RT was «the No. 1 news source in terms of engagements on Facebook» December 2021-January 2022, (according to this CrowdTangle data).[222]

Reliable figures for RT’s worldwide audience were not available as of 2015.[198] In the United States, RT typically pays cable and satellite services to carry its channel in subscriber packages.[224] In 2011, RT was the second most-watched foreign news channel in the United States (after BBC World News),[228] and the number one foreign network in five major U.S. urban areas in 2012.[229] It also rated well among younger Americans under 35 and in inner city areas.[229]

In the UK, the Broadcasters’ Audience Research Board (BARB) has included RT in the viewer data it publishes since 2012.[198] According to their data, approximately 2.5 million Britons watched RT during the third quarter of 2012, making it the third most-watched rolling news channel in Britain, behind BBC News and Sky News (not including Sky Sports News).[183][230][231] RT was soon overtaken by Al Jazeera English,[232] and viewing figures dropped to about 2.1 million by the end of 2013.[233] For comparison, it had marginally fewer viewers than S4C, the state-funded Welsh language broadcaster,[234] or minor channels such as Zing, Viva and Rishtey.[235] According to internal documents submitted for Kremlin review, RT’s viewership amounted to less than 0.1 percent of Europe’s television audience, except in Britain, where 2013 viewership was estimated at 120,000 persons per day.[224] According to the leaked documents, RT was ranked 175th out of 278 channels in Great Britain in May 2013, or fifth out of eight cable news channels.[224] In August 2015, RT’s average weekly viewing figure had fallen to around 450,000 (0.8 percent of the total UK audience), 100,000 fewer than in June 2012 and less than half that of Al Jazeera English.[198][236] In March 2016, the monthly viewing was figure 0.04%.[237]

Latin America is the second most significant area of influence for internet RT (rt.com). In 2013, RT ascended to the ranks of the 100 most watched websites in seven Latin American countries.[238]

A Pew Research survey of the most popular news videos on YouTube in 2011–12 found RT to be the top source with 8.5 percent of posts, 68 percent of which consisted of first-person video accounts of dramatic worldwide events, likely acquired by the network rather than created by it.[239][240] In 2013, RT became the first television news channel to reach 1 billion views on YouTube.[44] In 2014, its main (English) channel was reported have 1.4 million subscribers.[241]

Followers

In 2013, RT became «the first news network to surpass 1 billion views on YouTube».[168]

As of shortly after the invasion of Ukraine and blocking of RT by tech companies, RT’s «main Facebook channel has more than 7 million followers» (some of which are located in Europe where the channel is blocked). RT’s YouTube account had «roughly 4.65 million followers in English and 5.94 million in Spanish».[168]

Impact

RT has some effect on viewers’ political opinions, according to a 2021 study in the journal Security Studies. Viewers exposed to RT became more likely «to support the withdrawal of the United States «from its role as a cooperative global leader» than those who did not watch RT by 10–20%. «This effect is robust across measures, obtains across party lines, and persists even when we disclose that RT is financed by the Russian government.» However, exposure to RT had no measurable «effect on Americans’ views of domestic politics or the Russian government.»[242]

According to author Peter Pomerantsev, a large audience rating is not RT’s principal goal. Their campaigns are «for financial, political and media influence.”[243] RT (and Sputnik) «create the fodder» used by «thousands of fake news propagators» and provide an outlet for material hacked from targets it wishes to harm in the service of Russian (government) interests. RT also serves to make friends with people «useful» to the Russian state, such as Michael Flynn (retired United States Army lieutenant general and dismissed director of the Defense Intelligence Agency and U.S. National Security Advisor[244] in the early days of the Trump administration) who was paid «a reported $40,000 to come to RT’s anniversary celebration in Moscow and sit near Mr. Putin.»[243]

Programming

In 2008, Heidi Brown wrote in Forbes that «the Kremlin is using charm, good photography and a healthy dose of sex appeal to appeal to a diverse, skeptical audience. The result is entertaining – and ineffably Russian.» She added that Russia Today has managed to «get foreigners to at least consider the Russian viewpoint – however eccentric it may be…»[245] Matt Field in Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists described RT as «applying high-quality graphics and production values to its stories», often focusing «on polarizing issues that aren’t necessarily top-of-mind for viewers» and sometimes «strikingly at odds with Russian President Vladimir Putin’s own views».[246]

According to Tim Dowling, writing in The Guardian, «Fringe opinion takes center stage» on RT. «Reporting is routinely bolstered by testimony from experts you have never heard of, representing institutions you have never heard of.»[247]

The Alyona Show

The Alyona Show, hosted by Alyona Minkovski, ran from 2009 to 2012 (when Minkovski left RT to join The Huffington Post). Daily Beast writer Tracy Quan described The Alyona Show as «one of RT’s most popular vehicles».[248] The New Republic columnist Jesse Zwick wrote that one journalist told him that Minkovski is «probably the best interviewer on cable news».[249] Benjamin R. Freed wrote in the avant-garde culture magazine SOMA that «The Alyona Show does political talk with razor-sharp wit.»[250] David Weigel called the show «an in-house attempt at a newsy cult hit» and noted that «her meatiest segments were about government spying, and the Federal Reserve, and America’s undeclared wars».[101] Minkovski had complained about being characterized as if she was «Putin’s girl in Washington» or as being «anti-American».[250] After Minkovski argued that Glenn Beck was «not on the side of America. And the fact that my channel is more honest with the American people is something you should be ashamed of», Columbia Journalism Review writer Julia Ioffe asked: «since when does Russia Today defend the policies of any American president? Or the informational needs of the American public, for that matter?»[43]

Adam vs. the Man

From April to August 2011, RT ran a half-hour primetime show Adam vs. the Man,[251][252][253] hosted by former Iraq War Marine veteran and high-profile anti-war activist Adam Kokesh. David Weigel writes that Kokesh defended RT’s «propaganda» function, saying «We’re putting out the truth that no one else wants to say. I mean, if you want to put it in the worst possible abstract, it’s the Russian government, which is a competing protection racket against the other governments of the world, going against the United States and calling them on their bullshit.»[101]

World Tomorrow

Reviewing the first episode of Julian Assange’s show World Tomorrow, The Independent noted that Assange, who was under house arrest, was «largely deferential» in asking some questions of Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah, who himself was in hiding. However, he also asked tough questions such as why Nasrallah had not supported Arab revolts against Syrian leaders, when he had supported them in Tunisia, Yemen, Egypt, and other countries.[119] The New York Times journalist Allesandra Stanley wrote that «practically speaking, Mr. Assange is in bed with the Kremlin, but on Tuesday’s show he didn’t put out» and that he «behaved surprisingly like a standard network interviewer».[116] Douglas Lucas in Salon wrote that the RT deal «may just be a profitable way for him to get a gigantic retweet».[123] Glenn Greenwald, who has been a guest on RT,[254] wrote that RT presenting the Julian Assange show led to «a predictable wave of snide, smug attacks from American media figures».[255]

Other shows

Marcin Maczka writes that RT’s ample financing has allowed RT to attract experienced journalists and use the latest technology.[192] RT anchors and correspondents tend to concentrate on controversial world issues such as the financial and banking scandals, corporate impact on the global economy, and western demonstrations. It has also aired views by various conspiracy theorists, including neo-Nazis, white supremacists, and Holocaust deniers (presented as «human rights activists»).[256] News from Russia is of secondary importance and such reports emphasize Russian modernisation and economic achievements, as well as Russian culture and natural landscapes, while downplaying Russia’s social problems or corruption.[94][192]

#1917LIVE

In 2017, RT ran a mock live tweeting program under the hashtag «#1917LIVE» to mark the 100th anniversary of the Russian Revolution.[257]

The #1917Live project had multimedia social plug-ins, such as Periscope live streaming, as well as virtual reality panoramic videos.[258]

Programs

RT’s feature programs include (with presenters parenthesised):[259][260]

Current

- On Contact (Chris Hedges)

- Renegade Inc. (Ross Ashcroft)

- Keiser Report (Max Keiser with Stacy Herbert) from RT UK

- America’s Lawyer (Mike Papantonio)

- Interview (various presenters)

- Going Underground (Afshin Rattansi) from RT UK

- News Thing (Sam Delaney)

- Watching the Hawks (Tyrel Ventura, Sean Stone, and Tabetha Wallace)

- SophieCo (Sophie Shevardnadze)

- CrossTalk (Peter Lavelle)

- Sputnik (George Galloway) from RT UK

- Politicking (Larry King)

- News Views Hughes

- On the Touchline with José Mourinho

- News with Rick Sanchez

- The Alex Salmond Show (Alex Salmond; suspended)[261]

- Worlds Apart with Oksana Boyko[262]

- In Question

- Raw Take

- Interdit d’interdire (Frédéric Taddeï, resigned)[263] from RT France

Former

RT’s former on-air staff included 25 people from RT America.[264]

- Off the grid (Jesse Ventura)

- Capital Account (Lauren Lyster) from RT America

- Why you should care! (Tim Kirby)

- Breaking the Set (Abby Martin)

- In Context (Peter Lavelle)

- Spotlight (Aleksandr Gurnov)

- On the Money (Peter Lavelle)

- World Tomorrow (Julian Assange)

- Moscow Out (Martyn Andrews)

- Adam vs. the Man (Adam Kokesh)

- The Alyona Show (Alyona Minkovski)

- The Big Picture (Thom Hartmann) from RT America

- The News with Ed Schultz (Ed Schultz)

- Redacted Tonight (Lee Camp) from RT America

- How to Watch the News with Slavoj Žižek

- Larry King Now (Larry King)

On-air staff

RT’s current on-air staff includes 25 people from RT News, and 8 from RT UK.[264] Notable members of RT’s current and former staff include:

Guests

According to Jesse Zwick, RT persuades «legitimate experts and journalists» to appear as guests by allowing them to speak at length on issues ignored by larger news outlets. It frequently interviews progressive and libertarian academics, intellectuals and writers from organisations like The Nation, Reason, Human Events, Center for American Progress[249] and the Cato Institute[101] who are critical of United States foreign and civil liberties policies.[249] Julian Assange of WikiLeaks and Noam Chomsky, the leftist critic of Western policies are «favorites».[243] RT also features little-known commentators including anarchists, anti-globalists and left-wing activists.[192] Journalist Danny Schechter holds that a primary reason for RT’s success in the United States is that RT is «a force for diversity» which gives voice to people «who rarely get heard in current mainstream US media».[96] Examples of this include «a twelve-minute interview» in March 2010 «with Hank Albarelli, a self-described American ‘historian’ who claims that the CIA is testing dangerous drugs on unwitting civilians», and RT’s asking for commentary on the 2010 Haiti earthquake from «Carl Dix, a representative of the American Revolutionary Communist Party».[43]

In 2010, journalist and blogger Julia Ioffe described RT as being «provocative just for the sake of being provocative» in its choice of guests and issue topics, featuring a Russian historian who predicted that the United States would soon be dissolved, showing speeches by Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez, reporting on homelessness in America, and interviewing the chairman of the New Black Panther Party. She wrote that in attempting to offer «an alternate point of view, it is forced to talk to marginal, offensive, and often irrelevant figures».[43][59] A 2010 Southern Poverty Law Center report stated that RT extensively covered the «birther» and the «New World Order» conspiracy theories and interviewed militia organizer Jim Stachowiak and white nationalist Jared Taylor.[256] An Al Jazeera English article stated that RT has a penchant «for off-beat stories and conspiracy theories».[265] RT Editor-in-Chief Margarita Simonyan told Nikolaus von Twickel of The Moscow Times that RT started to grow once it became provocative and that controversy was vital to the channel. She said that RT’s task was not to polish Moscow’s reputation.[22] The news channel has also been criticized for its lack of objectivity in its coverage of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict.[266] Miko Peled, the Israeli peace activist who has called the peace process «a process of apartheid & colonization» is a frequent guest on RT.

Notable guests have included think tank intellectuals like Jared Bernstein,[101] John Feffer and Lawrence Korb; journalists and writers Jacob Sullum, Pepe Escobar,[249] and Brian Doherty,[267] and heads of state, including Ecuador’s Rafael Correa,[267] and Syria’s Bashar al-Assad.[268] Nigel Farage, the leader of UK Independence Party from 2010 to 2016, appeared on RT eighteen times from 2010 to 2014.[234][269] Steve Bannon has stated that he has appeared on RT «probably 100 times or more».[270] Manuel Ochsenreiter, a neo-Nazi, has repeatedly appeared on RT to represent the German point of view.[271] RT News has also frequently hosted Richard B. Spencer, an American white supremacist airing his opinions in support of Syrian president Bashar al-Assad,[272] and has hosted Holocaust denier Ryan Dawson, presenting him as a human rights activist.[273] Such figures as Alex Jones, Jim Marrs, David Ray Griffin, and Webster Tarpley have appeared on RT to advance conspiracy theories about topics such as the September 11 attacks, the Bilderberg group, and the «New World Order».[60]: 308 [62]

Content

RT has presented itself as a global network «like the BBC or France 24», differing from them in offering “alternative views” ignored by the «Western-dominated news media». Many Western countries, in contrast, regard RT not just as a propaganda organ, but as «the slickly produced heart of a broad, often covert disinformation campaign designed to sow doubt about democratic institutions and destabilize the West».[243]

According to Steven Erlanger, RT provides «hard news and top-notch graphics» and a «mix with interviews from all sorts of people: well known and obscure, left and right. … if there is any unifying character to RT, it is a deep skepticism of Western and American narratives of the world and a fundamental defensiveness about Russia and Mr. Putin.»[243]

Propaganda and related issues

RT’s editor-in-chief, Margarita Simonyan, has described RT as giving Russia «soft power», and being the same kind of «tool» for Russia that the «BBC or CNN» are «for the UK and USA». In 2012, she stated that RT waged «an information war … with the entire Western world» during the Russo-Georgian War.[74][73][17]

Observers have criticized the state-supported/controlled nature of RT as an instrument of propaganda.

In 2005, Pascal Bonnamour, the head of the European department of Reporters Without Borders, called the newly announced network «another step of the state to control information».[274] In a 2005 interview with U.S. government-owned external broadcaster Voice of America, Russian-Israeli blogger Anton Nosik said the creation of RT «smacks of Soviet-style propaganda campaigns».[275] In 2009, Luke Harding (then Moscow correspondent for The Guardian) described RT’s advertising campaign in the United Kingdom as an «ambitious attempt to create a new post-Soviet global propaganda empire».[45] In Russia, Andrey Illarionov, former advisor to Vladimir Putin, has called the channel «the best Russian propaganda machine targeted at the outside world».[94][192] Chess grandmaster Garry Kasparov, speaking after the launch of RT America, said: «Russia Today is an extension of the methods and approach of the state-controlled media inside Russia, applied in a bid to influence the American cable audience».[46]

Others have commended its promotion and discussion of issues ignored or just not given enough time by the mainstream news media. In E-International Relations, researcher Precious N Chatterje-Doody stated that RT viewers tend to recognize RT’s state-controlled status, and that they choose to watch RT for its «non-mainstream» story selection and its use of technology. She asserted that if RT broadcast only «blatant propaganda», it would not retain its audience.[276]

According to Adam Johnson in The Nation magazine, «while Russia Today toes the Kremlin’s line on foreign policy, it also provides an outlet to marginalized issues and voices stateside. RT, for example, has covered the recent prison strikes—the largest in American history—twice. So far CNN, MSNBC, NPR, and Rutenberg’s employer, The New York Times, haven’t covered them at all. RT aggressively covered Occupy Wall Street early on while the rest of corporate US media were marginalizing from afar (for this effort, RT was nominated for an Emmy Award).»[277] John Feffer, co-director of Foreign Policy in Focus says he appears on RT as well as the U.S.-funded Voice of America and Radio Free Asia, commented «I’ve been given the opportunity to talk about military expenditures in a way I haven’t been given in U.S. outlets». On the fairness issue, he said: «You’re going to find blind spots in the coverage for any news organization».[249]

Among the complaints of RT are the quality of its journalism and general production of «propaganda and disinformation». Graduate students at Columbia School of Journalism monitored RT’s (US) output for much of 2015, and found «RT ignores the inherent traits of journalism—checking sources, relaying facts, attempting honest reportage» and «you’ll find ‘experts’ lacking in expertise, conspiracy theories without backing, and, from time to time, outright fabrication for the sake of pushing a pro-Kremlin line», according to Casey Michel, who worked on the project.[278][279] The results were compiled in a Tumblr blog.[280] Media analyst Vasily Gatov wrote in a 2014 Moscow Times article that sharp ethical and reporting skills are not required for Russian media employees, including RT.[281] RT has been deprecated by the Wikipedia community as an unreliable source of information, with consensus being that it is «a mouthpiece of the Russian government that engages in propaganda and disinformation.»[282]

In a 2022 research paper comparing RT and China Global Television Network (CGTN)’s coverage of the 2020 United States presidential election, Martin Moore and Thomas Colley of King’s College London conceptualized RT as operating using a «partisan parasite» propaganda model, noting that it «often covers topics and people that would mainly be familiar to US audiences, but which are of little international salience or relevance», and that it rarely covers Russia except through the lens of U.S. politics. They also noted: «Its content selection, partisan framing and vernacular style is similar to right-wing US outlets like Fox News, NewsMax and One America News Network (OANN).»[283]

RT has been accused of different approaches to disinformation:

- Focusing on «presenting a negative picture of the United States and ‘the West'», rather than extolling «Russia’s virtues directly», publishing conspiracy theories about the West, criticizing U.S. influence abroad, and presenting Russia as «a ‘global underdog'» to U.S. hegemony. (Michael Dukalskis in his 2021 book on tactics used by authoritarian regimes to construct a positive image of their regimes).[63]

- Normally giving reporters and presenters considerable latitude, and saving straight-up pro-Russian government «message control» (propaganda), for «highly sensitive issues», such as the Russo-Georgian War or the trial of Mikhail Khodorkovsky, (Julia Ioffe).[43]

- Functioning in some circumstances, (like the 2016 U.S. presidential election), as a part of a larger Russian disinformation apparatus with the goal of undermining «public faith in the U.S. democratic process,” and damaging enemies (like Hillary Clinton). RT and other state-funded Russian media, publicize «real information, some open and some hacked» (i.e. stolen), along with «false reports» they’ve created. These are «amplified on social media, sometimes by computer bots that send out thousands of Facebook and Twitter messages.» (Steven Erlanger, quoting U.S. agencies).[243]

- Only rarely taking a «single, anti-Western media line on any given story», which would be «too obvious». Instead, presenting «gaggles of competing and contradicting narratives which together create the impression that the truth is indecipherable». (Lithuania’s STRATCOM Colonel).[284] RT’s «main message is that you cannot trust the western media». It seems «dedicated to the proposition that after the notion of objectivity has evaporated, all stories are equally true.» (Peter Pomerantsev, writing in The Guardian in 2015)[285] Using a strategy of distributing fake stories in «high-volume and multichannel, rapid, continuous, and repetitive» manner, with no regard to consistency. This «firehose of falsehood» makes propaganda difficult to counter. (Christopher Paul, Miriam Matthews of RAND Corporation).[286] Though viewers may still oppose Russian policy and dislike Putin, RT’s goal is for “a bit» of disinformation mud to «stick” to viewers and their doubts about Western institutions to grow. (Robert Pszczel, who ran NATO’s information office in Moscow and watches Russia and the western Balkans for NATO.)[243]

- Pushing different themes in different countries, which are often contradictory but all serve the Russian government’s interests:

- presenting itself as a liberal alternative in the United States, but as the flagship of resurgent nationalist parties in Europe. (Patrick Hilsman)[287]

- warning domestic Russian audiences of the dangers of COVID-19 and the need for preventive measures, while saturating English, German, French, Spanish, and Arabic-language platforms with COVID-19 misinformation and conspiracy theories.[213][214][288]

- RT (and other Russian propaganda media) may broadcast different «themes or messages», different accounts of «contested events», and may change their account (their «falsehood or misrepresentation») if it is «exposed or … not well received», moving «on to a new (though not necessarily more plausible) explanation».[289] An example being Russian media explanations for killing of 283 passengers and 15 crew from the downing of Malaysia Airlines Flight 17 on 17 July 2014 while the plane was flying over pro-Russian separatist-controlled territory in Ukraine. The Dutch Safety Board (DSB) and the Dutch-led joint investigation team (JIT), concluded that the airliner was downed by a Russian Buk surface-to-air missile launched from the separatist-controlled territory,[290][291] and American, German, Dutch and Australia investigations held Russia responsible. Russian media (LifeNews) first reported separatists had shot down a «Ukrainian Air Force An-26 transport plane» with a missile, calling it «a new victory for the Donetsk militia».[292][293][294] Later, after it was clear the plane was civilian, offering a variety of theories of how the Ukrainian military was responsible.[295] One theory offered and later discarded by RT was that the airliner may have been shot down by Ukraine in a failed attempt to assassinate Vladimir Putin, in a plot which was organised by Ukraine’s «Western backers». (However Putin’s flight route was hundreds of kilometres north of Ukraine.)[296][297]

Disinformation and conspiracy theories

Academics, fact-checkers, and news reporters (including some current and former RT reporters) have identified RT as a purveyor of disinformation[58] and conspiracy theories.[65]

In 2010, The Economist magazine observed that RT’s programming, while sometimes interesting and unobjectionable, and sometimes «hard-edged», also presents «wild conspiracy theories» that can be regarded as «kooky».[59]

A 2013 article in Der Spiegel said that RT «uses a chaotic mixture of conspiracy theories and crude propaganda», pointing to a program that «mutated» the Boston Marathon bombing into a U.S. government conspiracy.[44]

The launch of RT UK was the subject of much comment in the British press in late 2014.[298] In The Observer, Nick Cohen accused the channel of consciously spreading conspiracy theories and of being a «prostitution of journalism».[299] Oliver Kamm, a columnist for The Times, called on British broadcasting regulator Ofcom to act against this «den of deceivers».[300]

Journalists at The Daily Beast and The Washington Post have observed that RT employs Tony Gosling, an exponent of long-discredited theories concerning the alleged control of the world by Illuminati and the Czarist antisemitic forgery The Protocols of the Elders of Zion.[301][302]

RT has broadcast stories about microchips being implanted into office workers in the EU to make them more «submissive»; about the «majority» of Europeans supporting Russian annexation of Crimea; the EU preparing «a form of genocide» against Russians; in Germany it falsely reported about a kidnapping of a Russian girl; that «NATO planned to store nuclear weapons in Eastern Europe»; that Hillary Clinton fell ill; it has also on many occasions misrepresented or invented statements from European leaders.[303][304][305][306]

In 2017, RT started its own fact-checking project, FakeCheck, in response to accusations of spreading fake news.[49][307] The Poynter Institute conducted a content analysis of FakeCheck and concluded it «mixes some legitimate debunks with other scantily sourced or dubiously framed ‘fact checks.'»[307] Ben Nimmo of the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab found that four out of nine articles published in its first two weeks contained «inaccuracies and possible bias with irrelevant or insufficient evidence.»[308]

From the time of the 2014 pro-Russia unrest in Ukraine RT has repeatedly been exposed for producing fake news.

[309] In 2017, the channel was involved in a fake news scandal about a ‘Putin burger’ it claimed was on the menu in a New York diner, to celebrate the birthday Russian president, Vladimir Putin. The ‘Putin burger’ story was quickly exposed as a fabrication, and RT removed it from their site.[310]

When caught out in fakes, RT has frequently deleted the material from their site, and made no further comment.[311]

In 2022, the Centre for Democratic Integrity (CDI) published a comprehensive report «RT in Europe and beyond» which in detail describes disinformation and divisive activities of RT against European audience with focus on regional editions (French, Spanish, German, British), documenting specific disinformation campaigns.[312]

In 2022, Martin Moore and Thomas Colley of King’s College London noted that RT’s coverage of the 2020 United States presidential election was anti-Joe Biden and pro-Trump, with RT promoting the Trump campaign’s unfounded claims that Biden was the head of a «crime family», as well as allegations that Biden’s son Hunter made corrupt business deals in Ukraine and China and possessed pictures of underage girls. RT also questioned Joe Biden’s fitness for office and promoted unfounded rumors that he could only debate effectively with the use of headpieces and/or performance-enhancing drugs. Following the election, RT uncritically promoted Trump’s unfounded claims of electoral fraud, and Moore and Colley noted that in its coverage of the electoral process, RT claimed that the process was «dysfunctional, fraudulent or futile».[283]

Treatment of Putin and Medvedev

A 2007 article in The Christian Science Monitor stated that RT reported on the good job Putin was doing in the world and next to nothing on things like the conflict in Chechnya or the murder of government critics.[313] According to a 2010 report by The Independent, RT journalists have said that coverage of sensitive issues in Russia is allowed, but direct criticism of Vladimir Putin or President Dmitry Medvedev was not.[96] Masha Karp wrote in Standpoint magazine that contemporary Russian issues «such as the suppression of free speech and peaceful demonstrations, or the economic inefficiency and corrupt judiciary, are either ignored or their significance played down».[314] In 2008, Stephen Heyman wrote in The New York Times that in RT’s Russia, «corruption is not quite a scourge but a symptom of a developing economy».[94]

Anti-Americanism and anti-Westernism

The New Republic writer James Kirchick accused the network of «often virulent anti-Americanism, worshipful portrayal of Russian leaders».[315] Edward Lucas wrote in The Economist (quoted in Al Jazeera English) that the core of RT was «anti-Westernism».[265] Julia Ioffe wrote: «Often, it seemed that Russia Today was just a way to stick it to the U.S. from behind the façade of legitimate newsgathering.»[43] Shaun Walker wrote in The Independent that RT «has made a name for itself as a strident critic of US policy».[316] Allesandra Stanley wrote in The New York Times that RT is «like the Voice of America, only with more money and a zesty anti-American slant».[116] David Weigel writes that RT goes further than merely creating distrust of the United States government, to saying, in effect: «You can trust the Russians more than you can trust those bastards.»[101]

Russian studies professor Stephen F. Cohen stated in 2012 that RT does a lot of stories that «reflect badly» on the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, and much of Western Europe and that they are «particularly aggrieved by American sermonizing abroad». Citing that RT compares stories about Russia allowing mass protests of the 2011–2012 Russian election protests with those of U.S. authorities nationwide arresting members of the Occupy movement. Cohen states that despite the pro-Kremlin slant, «any intelligent viewer can sort this out. I doubt that many idiots find their way to RT».[249]

RT America has described journalists as «Russiagate conspiracy theorists» for covering Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s report on Russian interference in the 2016 election.[317]

Russian journalist, former press secretary of the head of the UN Mission in South Africa, Yuri Sigov, wrote that when covering Canada, Russia Today presents information selectively. This is almost always negative information aimed at fulfilling political orders.[318]

Israeli–Palestinian conflict

RT, particularly the former RT presenter Abby Martin, has been accused of being anti-Israel and pro-Palestinian by The Algemeiner and Israel National News.[319][320] Israeli foreign minister Avigdor Lieberman made a complaint[clarification needed] to Putin at their official meeting in 2012.[321]

Climate change denial

In November 2021, a study by the Center for Countering Digital Hate described RT as being among «ten fringe publishers» that together were responsible for nearly 70 percent of Facebook user interactions with content that denied climate change. Facebook disputed the study’s methodology.[322][323][324]

COVID-19 misinformation

Compared to RT’s coverage of the COVID-19 pandemic for its viewers in Russia, RT’s coverage of the pandemic for its international viewers was saturated with COVID-19 misinformation and conspiracy theories. RT urged domestic Russian audiences to vaccinate and wear masks to prevent COVID-19, while advocating against virus-prevention measures on its English, German, French, Spanish, and Arabic-language platforms.[213][214][288][325]

Responses

States

European Union – Sanctions against Dmitry Kiselyov, the head of Russia’s state-controlled Rossiya Segodnya and RT television presenter, have been in place since the 2014 invasion and annexation of Ukraine’s Crimea. The EU Council cites Kiselyov to be a «central figure of the government propaganda supporting the deployment of Russian forces in Ukraine». Initially, Russian state-owned media outlets were not banned and continued to be available in the EU, with the exception of Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland.[326][327][328] The European Parliament Special Committee on Foreign Interference in all Democratic Processes in the European Union, including Disinformation (INGE) described RT as «actively engaging in disinformation activities» and highlighted that RT and Sputnik are pushing local broadcasters in Europe off from the market thanks to massive funding from Russian Federation.[329] Editor-in-chief Margarita Simonyan was sanctioned by the European Union on 23 February 2022 when Russia recognized the Donetsk and Luhansk breakaway states.[330] On 27 February 2022, the EU banned RT and Sputnik from broadcasting in its member countries, following the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine.[146]

Australia – Minister for Communications Paul Fletcher requested the partially Australian government funded public service broadcaster SBS suspend broadcasts of RT and NTV news programming on its World Watch platform. Fletcher stated, «Given the current actions of the Russian government [2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine], and the lack of genuinely independent Russian media, this is a responsible decision.» SBS suspended the aforementioned broadcasts on 25 February 2022.[331][332] The RT channel was removed from Australian pay TV provider Foxtel’s listings the next day due to concerns about the situation in Ukraine.[333][334]

Canada – On 16 March 2022, the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission banned RT and RT France from broadcasting in Canada.[335]

Germany – After failing to obtain a broadcast license compliant with the State Media Treaty [de], RT DE was banned in Germany by the Commission for Licensing and Supervision [de] (ZAK) on 2 February 2022.[336] The Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs responded with «retaliatory measures» to remove German broadcaster Deutsche Welle from Russia.[337]

Gibraltar – Chief Minister Fabian Picardo requested a nationwide ban of RT on 25 February 2022 in response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, describing RT as «a dangerous source of disinformation that Gibraltar cannot accept on its networks». Television providers in Gibraltar agreed to suspend broadcasts of RT.[338]

Latvia – At the end of June 2020, after new amendments to the Law on Electronic Media were made, seven RT channels were banned in Latvia for being under the control of Dmitry Kiselyov who had been sanctioned by the European Union since 2014. Chairperson of the National Electronic Mass Media Council Ivars Āboliņš said they will be asking all EU state regulators to follow their example and restrict RT in their territory.[339][77] Kiselyov called the decision «an indicator of the level of stupidity and ignorance of the Latvian authorities, blinded by Russophobia».[340]

Lithuania – Linas Antanas Linkevičius, Lithuania’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, posted on Twitter on 9 March 2014 amid the Crimean crisis, «Russia Today propaganda machine is no less destructive than military marching in Crimea».[341][342] It was banned by the Radio and Television Commission of Lithuania on 8 July 2020.[78] The decision of both Latvian and Lithuanian authorities was criticised by Reporters Without Borders as «misuse of the EU sanctions policy».[343]

Poland – The National Broadcasting Council banned RT in Poland on 24 February 2022 in response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine.[344][345]

Ukraine – RT has been banned in Ukraine by the Ministry of Internal Affairs since August 2014, following the invasion and annexation of Ukrainian territory.[76]

United Kingdom – On 18 March 2022, ANO TV Novosti’s broadcasting license was revoked by Ofcom, effectively banning RT from being broadcast. This was taken in the wake of RT UK being funded by the Russian government, which, when combined with their promotion of Russian state narratives with regards to sanctions and its invasion of Ukraine, was deemed a violation of neutrality standards.[346] This came after an investigation was launched on 2 March 2022 in these matters, also involving the invasion.[347]

United States – In September 2017, the US Department of Justice compelled RT to file paperwork under the Foreign Agents Registration Act in the United States.[348] Previously, the United States Secretary of State John Kerry had referred to RT as a state-sponsored «propaganda bullhorn» and he continued by saying, «Russia Today [sic] network has deployed to promote president Putin’s fantasy about what is playing out on the ground. They almost spend full-time devoted to this effort, to propagandize, and to distort what is happening or not happening in Ukraine.»[349] RT responded that they wanted «an official response from the U.S. Department of State substantiating Mr. Kerry’s claims».[350] Richard Stengel from the U.S. Department of State responded.[351] Stengel stated in his response, «RT is a distortion machine, not a news organization», concluding that «the network and its editors should not pretend that RT is anything other than another player in Russia’s global disinformation campaign against the people of Ukraine and their supporters». However, Stengel supports RT’s right to broadcast in the United States.[352]

Political involvement

In April 2017, during his successful run for President of France, Emmanuel Macron’s campaign team banned both RT and the Sputnik news agency from campaign events. A Macron spokesperson said the two outlets showed a «systematic desire to issue fake news and false information».[353] Macron later said during a press conference that RT and Sputnik were «agencies of influence and propaganda, lying propaganda—no more, no less».[354] RT editor-in-chief Margarita Simonyan characterized Macron’s remarks on RT as an attack on freedom of speech.[355]

In October 2017, Twitter banned both RT and Sputnik from advertising on their social networking service amid accusations of Russian interference in the 2016 United States elections, sparking an angry response from the Russian foreign ministry.[356][357] Twitter in August 2020 began to identify RT, along with other Russian and Chinese media outlets, as «state-affiliated media» in a prominent place at the top of their accounts on the social media platform.[358][359]

In November 2017, Alphabet chairman Eric Schmidt announced that Google will be «deranking» stories from RT and Sputnik in response to allegations about election meddling by President Putin’s government, provoking an accusation of censorship from both outlets.[360]

In March 2018, John McDonnell, the Shadow Chancellor of the British Labour Party, advised fellow Labour MPs to boycott RT and said he would no longer appear on the channel. He said: «We tried to be fair with them and as long as they abide by journalistic standards that are objective that’s fine but it looks as if they have gone beyond that line». A party representative said: «We are keeping the issue under review».[361]

In July 2019, the UK Foreign Office banned both RT and Sputnik from attending the Global Conference for Media Freedom in London for «their active role in spreading disinformation». The Russian Embassy called the decision «direct politically motivated discrimination», while RT responded in a statement: «It takes a particular brand of hypocrisy to advocate for freedom of press while banning inconvenient voices and slandering alternative media.»[362]

Other responses

2008–2012

During the 2008 South Ossetia War, RT correspondent William Dunbar resigned after the network refused to let him report on Russian airstrikes of civilian targets, stating, «any issue where there is a Kremlin line, RT is sure to toe it».[363] According to Variety, sources at RT confirmed that Dunbar had resigned, saying that it was not over bias. One senior RT journalist told the magazine, «the Russian coverage I have seen has been much better than much of the Western coverage… Russian news coverage is largely pro-Russia, but that is to be expected.»[364]

Shaun Walker, the Moscow correspondent for The Independent, said that RT had «instructed reporters not to report from Georgian villages within South Ossetia that had been ethnically cleansed».[104] Julia Ioffe wrote that an RT journalist whose reporting deviated from «the Kremlin line that Georgians were slaughtering unarmed Ossetians» was reprimanded.[43] Human Rights Watch said that RT’s claim of 2,000 South Ossetian casualties was exaggerated.[365][366]

In 2012, Jesse Zwick of The New Republic criticized RT, stating it held that «civilian casualties in Syria are minimal, foreign intervention would be disastrous, and any humanitarian appeals from Western nations are a thin veil for a NATO-backed move to isolate Iran, China, and Russia». He wrote that RT wants to «make the United States look out of line for lecturing Russia».[249] Zwick also wrote that RT provided a «disproportionate amount of time» to covering libertarian Republican Ron Paul during his 2012 presidential campaign. Writing after her 2014 on-air resignation, Liz Wahl suggested the reason for this «wasn’t his message of freedom and liberty but his non-interventionist stance and consistent criticism of U.S. foreign policy. His message fit RT’s narrative that the United States is a huge bully.»[367] In a June 2011 broadcast of Adam vs. the Man, host Adam Kokesh endorsed fundraising for Paul, leading to a complaint to the Federal Election Commission charging a political contribution had been made by a foreign corporation. Kokesh said his cancellation in August was related to Paul’s aide Jesse Benton rather than the complaint.[253]