| Parthenon | |

|---|---|

|

Παρθενώνας |

|

The Parthenon in 1978 |

|

|

|

| General information | |

| Type | Temple |

| Architectural style | Classical |

| Location | Athens, Greece |

| Coordinates | 37°58′17″N 23°43′36″E / 37.9715°N 23.7266°E |

| Construction started | 447 BC[1][2] |

| Completed | 432 BC[1][2] |

| Destroyed | Partially in 1687 |

| Height | 13.72 m (45.0 ft)[3] |

| Dimensions | |

| Other dimensions | Cella: 29.8 by 19.2 m (98 by 63 ft) |

| Technical details | |

| Material | Pentelic Marble[4] |

| Size | 69.5 by 30.9 m (228 by 101 ft) |

| Floor area | 73 by 34 m (240 by 112 ft)[5] |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Iktinos, Callicrates |

| Other designers | Phidias (sculptor) |

The Parthenon (; Ancient Greek: Παρθενών, romanized: Parthenōn [par.tʰe.nɔ̌ːn]; Greek: Παρθενώνας, romanized: Parthenónas [parθeˈnonas]) is a former temple[6][7] on the Athenian Acropolis, Greece, that was dedicated to the goddess Athena during the fifth century BC. Its decorative sculptures are considered some of the high points of classical Greek art, an enduring symbol of Ancient Greece, democracy and Western civilization.[8][9]

The Parthenon was built in thanksgiving for the Hellenic victory over Persian Empire invaders during the Greco-Persian Wars.[10] Like most Greek temples, the Parthenon also served as the city treasury.[11][12]

Construction started in 447 BC when the Delian League was at the peak of its power. It was completed in 438 BC; work on the decoration continued until 432 BC. For a time, it served as the treasury of the Delian League, which later became the Athenian Empire. In the final decade of the 6th century AD, the Parthenon was converted into a Christian church dedicated to the Virgin Mary. After the Ottoman conquest in the mid-fifteenth century, it became a mosque. In the Morean War, a Venetian bomb landed on the Parthenon, which the Ottomans had used as a munitions dump, during the 1687 siege of the Acropolis. The resulting explosion severely damaged the Parthenon. From 1800 to 1803,[13] the 7th Earl of Elgin took down some of the surviving sculptures, now known as the Elgin Marbles, in an act widely considered, both in its time and subsequently, to constitute vandalism and looting.[14]

The Parthenon replaced an older temple of Athena, which historians call the Pre-Parthenon or Older Parthenon, that was demolished in the Persian invasion of 480 BC.

Since 1975, numerous large-scale restoration projects have been undertaken to preserve remaining artifacts and ensure its structural integrity.[15][16]

Etymology[edit]

The origin of the word «Parthenon» comes from the Greek word parthénos (παρθένος), meaning «maiden, girl» as well as «virgin, unmarried woman.» The Liddell–Scott–Jones Greek–English Lexicon states that it may have referred to the «unmarried women’s apartments» in a house, but that in the Parthenon it seems to have been used for a particular room of the temple.[17] There is some debate as to which room that was. The lexicon states that this room was the western cella of the Parthenon. This has also been suggested by J.B. Bury.[10] Jamauri D. Green claims that the Parthenon was the room where the arrephoroi, a group of four young girls chosen to serve Athena each year, wove a peplos that was presented to Athena during Panathenaic Festivals.[18] Christopher Pelling asserts that the name «Parthenon» means the «temple of the virgin goddess,» referring to the cult of Athena Parthenos that was associated with the temple.[19] It has also been suggested that the name of the temple alludes to the maidens (parthénoi), whose supreme sacrifice guaranteed the safety of the city.[20] In that case, the room originally known as the Parthenon could have been a part of the temple known today as the Erechtheion.[21]

In 5th-century BC accounts of the building, the structure is simply called ὁ νᾱός (ho naos; lit. «the temple»). Douglas Frame writes that the name «Parthenon» was a nickname related to the statue of Athena Parthenos, and only appeared a century after construction. He contends that «Athena’s temple was never officially called the Parthenon and she herself most likely never had the cult title parthénos.»[22] The ancient architects Iktinos and Callicrates appear to have called the building Ἑκατόμπεδος (Hekatómpedos; lit. «the hundred footer») in their lost treatise on Athenian architecture.[23] Harpocration wrote that some people used to call the Parthenon the «Hekatompedos,» not due to its size but because of its beauty and fine proportions.[23] The first instance in which Parthenon definitely refers to the entire building comes from the fourth century BC orator Demosthenes.[24] In the 4th century BC and later, the building was referred to as the Hekatompedos or the Hekatompedon as well as the Parthenon. Plutarch referred to the building during the first century AD as the Hekatompedos Parthenon.[25]

A 2020 study by Janric van Rookhuijzen supports the idea that the building known today as the Parthenon was originally called the Hekatompedon. Based on literary and historical research, he proposes that «the treasury called the Parthenon should be recognized as the west part of the building now conventionally known as the Erechtheion.»[26][27]

Because the Parthenon was dedicated to the Greek goddess Athena it has sometimes been referred to as the Temple of Minerva, the Roman name for Athena, particularly during the 19th century.[28]

Parthénos was also applied to the Virgin Mary (Parthénos Maria) when the Parthenon was converted to a Christian church dedicated to the Virgin Mary in the final decade of the 6th century.[29]

Function[edit]

Although the Parthenon is architecturally a temple and is usually called so, some scholars have argued that it is not really a temple in the conventional sense of the word.[30] A small shrine has been excavated within the building, on the site of an older sanctuary probably dedicated to Athena as a way to get closer to the goddess,[30] but the Parthenon apparently never hosted the official cult of Athena Polias, patron of Athens. The cult image of Athena Polias, which was bathed in the sea and to which was presented the peplos, was an olive-wood xoanon, located in another temple on the northern side of the Acropolis, more closely associated with the Great Altar of Athena.[31] The High Priestess of Athena Polias supervised the city cult of Athena based in the Akropolis, and was the chief of the lesser officials, such as the plyntrides, arrephoroi and kanephoroi.[32]

The colossal statue of Athena by Phidias was not specifically related to any cult attested by ancient authors[33] and is not known to have inspired any religious fervour.[31] Preserved ancient sources do not associate it with any priestess, altar or cult name.[34]

According to Thucydides, during the Peloponnesian War when Sparta’s forces were first preparing to invade Attica, Pericles, in an address to the Athenian people, said that the statue could be used as a gold reserve if that was necessary to preserve Athens, stressing that it «contained forty talents of pure gold and it was all removable,» but adding that the gold would afterward have to be restored.[35] The Athenian statesman thus implies that the metal, obtained from contemporary coinage,[36] could be used again if absolutely necessary without any impiety.[34] According to Aristotle, the building also contained golden figures that he described as «Victories.»[37] The classicist Harris Rackham noted that eight of those figures were melted down for coinage during the Peloponnesian War.[38] Other Greek writers have claimed that treasures such as Persian swords were also stored inside the temple.[citation needed] Some scholars, therefore, argue that the Parthenon should be viewed as a grand setting for a monumental votive statue rather than as a cult site.[39]

Archaeologist Joan Breton Connelly has recently argued for the coherency of the Parthenon’s sculptural programme in presenting a succession of genealogical narratives that track Athenian identity through the ages: from the birth of Athena, through cosmic and epic battles, to the final great event of the Athenian Bronze Age, the war of Erechtheus and Eumolpos.[40][41] She argues a pedagogical function for the Parthenon’s sculptured decoration, one that establishes and perpetuates Athenian foundation myth, memory, values and identity.[42][43] While some classicists, including Mary Beard, Peter Green, and Garry Wills[44][45] have doubted or rejected Connelly’s thesis, an increasing number of historians, archaeologists, and classical scholars support her work. They include: J.J. Pollitt,[46] Brunilde Ridgway,[47] Nigel Spivey,[48] Caroline Alexander,[49] and A. E. Stallings.[50]

Older Parthenon[edit]

The first endeavour to build a sanctuary for Athena Parthenos on the site of the present Parthenon was begun shortly after the Battle of Marathon (c. 490–488 BC) upon a solid limestone foundation that extended and levelled the southern part of the Acropolis summit. This building replaced a Hekatompedon temple («hundred-footer») and would have stood beside the archaic temple dedicated to Athena Polias («of the city»). The Older or Pre-Parthenon, as it is frequently referred to, was still under construction when the Persians sacked the city in 480 BC razing the Acropolis.[51][52]

The existence of both the proto-Parthenon and its destruction were known from Herodotus,[53] and the drums of its columns were visibly built into the curtain wall north of the Erechtheion. Further physical evidence of this structure was revealed with the excavations of Panagiotis Kavvadias of 1885–1890. The findings of this dig allowed Wilhelm Dörpfeld, then director of the German Archaeological Institute, to assert that there existed a distinct substructure to the original Parthenon, called Parthenon I by Dörpfeld, not immediately below the present edifice as previously assumed.[54] Dörpfeld’s observation was that the three steps of the first Parthenon consisted of two steps of Poros limestone, the same as the foundations, and a top step of Karrha limestone that was covered by the lowest step of the Periclean Parthenon. This platform was smaller and slightly to the north of the final Parthenon, indicating that it was built for a different building, now completely covered over. This picture was somewhat complicated by the publication of the final report on the 1885–1890 excavations, indicating that the substructure was contemporary with the Kimonian walls, and implying a later date for the first temple.[55]

If the original Parthenon was indeed destroyed in 480, it invites the question of why the site was left as a ruin for thirty-three years. One argument involves the oath sworn by the Greek allies before the Battle of Plataea in 479 BC[56] declaring that the sanctuaries destroyed by the Persians would not be rebuilt, an oath from which the Athenians were only absolved with the Peace of Callias in 450.[57] The cost of reconstructing Athens after the Persian sack is at least as likely a cause. The excavations of Bert Hodge Hill led him to propose the existence of a second Parthenon, begun in the period of Kimon after 468.[58] Hill claimed that the Karrha limestone step Dörpfeld thought was the highest of Parthenon I was the lowest of the three steps of Parthenon II, whose stylobate dimensions Hill calculated at 23.51 by 66.888 metres (77.13 ft × 219.45 ft).

One difficulty in dating the proto-Parthenon is that at the time of the 1885 excavation, the archaeological method of seriation was not fully developed; the careless digging and refilling of the site led to a loss of much valuable information. An attempt to make sense of the potsherds found on the Acropolis came with the two-volume study by Graef and Langlotz published in 1925–1933.[59] This inspired American archaeologist William Bell Dinsmoor to give limiting dates for the temple platform and the five walls hidden under the re-terracing of the Acropolis. Dinsmoor concluded that the latest possible date for Parthenon I was no earlier than 495 BC, contradicting the early date given by Dörpfeld.[60] He denied that there were two proto-Parthenons, and held that the only pre-Periclean temple was what Dörpfeld referred to as Parthenon II. Dinsmoor and Dörpfeld exchanged views in the American Journal of Archaeology in 1935.[61]

Present building[edit]

In the mid-5th century BC, when the Athenian Acropolis became the seat of the Delian League and Athens was the greatest cultural centre of its time, Pericles initiated an ambitious building project that lasted the entire second half of the century. The most important buildings visible on the Acropolis today – the Parthenon, the Propylaia, the Erechtheion and the temple of Athena Nike – were erected during this period. The Parthenon was built under the general supervision of Phidias, who also had charge of the sculptural decoration. The architects Ictinos and Callicrates began their work in 447, and the building was substantially completed by 432. Work on the decorations continued until at least 431.[citation needed]

The Parthenon was built primarily by men who knew how to work marble. These quarrymen had exceptional skills and were able to cut the blocks of marble to very specific measurements. The quarrymen also knew how to avoid the faults, which were numerous in the Pentelic marble. If the marble blocks were not up to standard, the architects would reject them. The marble was worked with iron tools – picks, points, punches, chisels, and drills. The quarrymen would hold their tools against the marble block and firmly tap the surface of the rock.[62]

A big project like the Parthenon attracted stonemasons from far and wide who travelled to Athens to assist in the project. Slaves and foreigners worked together with the Athenian citizens in the building of the Parthenon, doing the same jobs for the same pay. Temple building was a specialized craft, and there were not many men in Greece qualified to build temples like the Parthenon, so these men would travel and work where they were needed.[62]

Other craftsmen were necessary for the building of the Parthenon, specifically carpenters and metalworkers. Unskilled labourers also had key roles in the building of the Parthenon. They loaded and unloaded the marble blocks and moved the blocks from place to place. In order to complete a project like the Parthenon, many different labourers were needed.[62]

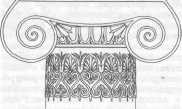

Architecture[edit]

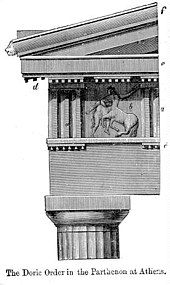

The Parthenon is a peripteral octastyle Doric temple with Ionic architectural features. It stands on a platform or stylobate of three steps. In common with other Greek temples, it is of post and lintel construction and is surrounded by columns (‘peripteral’) carrying an entablature. There are eight columns at either end (‘octastyle’) and seventeen on the sides. There is a double row of columns at either end. The colonnade surrounds an inner masonry structure, the cella, which is divided into two compartments. The opisthodomos (the back room of the cella) contained the monetary contributions of the Delian League. At either end of the building, the gable is finished with a triangular pediment originally occupied by sculpted figures.[63]

The Parthenon has been described as «the culmination of the development of the Doric order.»[64] The Doric columns, for example, have simple capitals, fluted shafts, and no bases. Above the architrave of the entablature is a frieze of carved pictorial panels (metopes), separated by formal architectural triglyphs, also typical of the Doric order. The continuous frieze in low relief around the cella and across the lintels of the inner columns, in contrast, reflects the Ionic order. Architectural historian John R. Senseney suggests that this unexpected switch between orders was due to an aesthetic choice on the part of builders during construction, and was likely not part of the original plan of the Parthenon.[65]

Measured at the stylobate, the dimensions of the base of the Parthenon are 69.5 by 30.9 metres (228 by 101 ft). The cella was 29.8 metres long by 19.2 metres wide (97.8 × 63.0 ft). On the exterior, the Doric columns measure 1.9 metres (6.2 ft) in diameter and are 10.4 metres (34 ft) high. The corner columns are slightly larger in diameter. The Parthenon had 46 outer columns and 23 inner columns in total, each column having 20 flutes. (A flute is the concave shaft carved into the column form.) The roof was covered with large overlapping marble tiles known as imbrices and tegulae.[66][67]

The Parthenon is regarded as the finest example of Greek architecture. John Julius Cooper wrote that «even in antiquity, its architectural refinements were legendary, especially the subtle correspondence between the curvature of the stylobate, the taper of the naos walls, and the entasis of the columns.»[68] Entasis refers to the slight swelling, of 4 centimetres (1.6 in), in the center of the columns to counteract the appearance of columns having a waist, as the swelling makes them look straight from a distance. The stylobate is the platform on which the columns stand. As in many other classical Greek temples,[69] it has a slight parabolic upward curvature intended to shed rainwater and reinforce the building against earthquakes. The columns might therefore be supposed to lean outward, but they actually lean slightly inward so that if they carried on, they would meet almost exactly 2,400 metres (1.5 mi) above the centre of the Parthenon.[70] Since they are all the same height, the curvature of the outer stylobate edge is transmitted to the architrave and roof above: «All follow the rule of being built to delicate curves», Gorham Stevens observed when pointing out that, in addition, the west front was built at a slightly higher level than that of the east front.[71]

It is not universally agreed what the intended effect of these «optical refinements» was. They may serve as a sort of «reverse optical illusion.»[72] As the Greeks may have been aware, two parallel lines appear to bow, or curve outward, when intersected by converging lines. In this case, the ceiling and floor of the temple may seem to bow in the presence of the surrounding angles of the building. Striving for perfection, the designers may have added these curves, compensating for the illusion by creating their own curves, thus negating this effect and allowing the temple to be seen as they intended. It is also suggested that it was to enliven what might have appeared an inert mass in the case of a building without curves. But the comparison ought to be, according to Smithsonian historian Evan Hadingham, with the Parthenon’s more obviously curved predecessors than with a notional rectilinear temple.[73]

Some studies of the Acropolis, including of the Parthenon and its facade, have conjectured that many of its proportions approximate the golden ratio.[74] More recent studies have shown that the proportions of the Parthenon do not match the golden proportion.[75][76]

Sculpture[edit]

«Parthenon Marbles» redirects here. For the works housed at the British Museum, see Elgin Marbles.

The cella of the Parthenon housed the chryselephantine statue of Athena Parthenos sculpted by Phidias and dedicated in 439 or 438 BC. The appearance of this is known from other images. The decorative stonework was originally highly coloured.[77] The temple was dedicated to Athena at that time, though construction continued until almost the beginning of the Peloponnesian War in 432. By the year 438, the Doric metopes on the frieze above the exterior colonnade and the Ionic frieze around the upper portion of the walls of the cella had been completed.[citation needed]

Only a small number of the original sculptures remain in situ. Most of the surviving sculptures are at the Acropolis Museum in Athens and (controversially) at the British Museum in London (see Elgin Marbles). Additional pieces are at the Louvre, the National Museum of Denmark, and museums in Rome, Vienna, and Palermo.[78]

In March 2022, the Acropolis Museum launched a new website with «photographs of all the frieze blocks preserved today in the Acropolis Museum, the British Museum and the Louvre.»[79]

Metopes[edit]

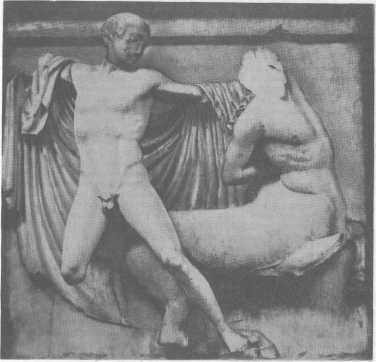

The frieze of the Parthenon’s entablature contained 92 metopes, 14 each on the east and west sides, 32 each on the north and south sides. They were carved in high relief, a practice employed until then only in treasuries (buildings used to keep votive gifts to the gods).[80] According to the building records, the metope sculptures date to the years 446–440. The metopes of the east side of the Parthenon, above the main entrance, depict the Gigantomachy (the mythical battle between the Olympian gods and the Giants). The metopes of the west end show the Amazonomachy (the mythical battle of the Athenians against the Amazons). The metopes of the south side show the Thessalian Centauromachy (battle of the Lapiths aided by Theseus against the half-man, half-horse Centaurs). Metopes 13–21 are missing, but drawings from 1674 attributed to Jaques Carrey indicate a series of humans; these have been variously interpreted as scenes from the Lapith wedding, scenes from the early history of Athens, and various myths.[81] On the north side of the Parthenon, the metopes are poorly preserved, but the subject seems to be the sack of Troy.[9]

The mythological figures of the metopes of the East, North, and West sides of the Parthenon had been deliberately mutilated by Christian iconoclasts in late antiquity.[82]

The metopes present examples of the Severe Style in the anatomy of the figures’ heads, in the limitation of the corporal movements to the contours and not to the muscles, and in the presence of pronounced veins in the figures of the Centauromachy. Several of the metopes still remain on the building, but, with the exception of those on the northern side, they are severely damaged. Some of them are located at the Acropolis Museum, others are in the British Museum, and one is at the Louvre museum.[83]

In March 2011, archaeologists announced that they had discovered five metopes of the Parthenon in the south wall of the Acropolis, which had been extended when the Acropolis was used as a fortress. According to Eleftherotypia daily, the archaeologists claimed the metopes had been placed there in the 18th century when the Acropolis wall was being repaired. The experts discovered the metopes while processing 2,250 photos with modern photographic methods, as the white Pentelic marble they are made of differed from the other stone of the wall. It was previously presumed that the missing metopes were destroyed during the Morosini explosion of the Parthenon in 1687.[84]

Frieze[edit]

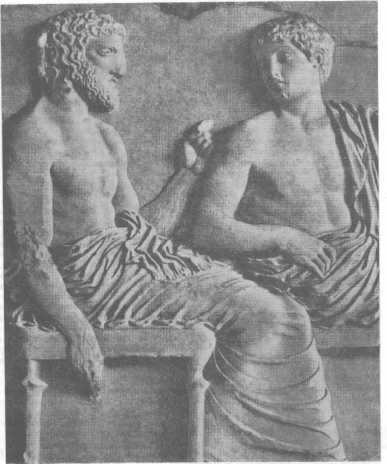

The most characteristic feature in the architecture and decoration of the temple is the Ionic frieze running around the exterior of the cella walls. The bas-relief frieze was carved in situ and is dated to 442–438.[citation needed]

One interpretation is that it depicts an idealized version of the Panathenaic procession from the Dipylon Gate in the Kerameikos to the Acropolis. In this procession held every year, with a special procession taking place every four years, Athenians and foreigners participated in honouring the goddess Athena by offering her sacrifices and a new peplos dress, woven by selected noble Athenian girls called ergastines. The procession is more crowded (appearing to slow in pace) as it nears the gods on the eastern side of the temple.[85]

Joan Breton Connelly offers a mythological interpretation for the frieze, one that is in harmony with the rest of the temple’s sculptural programme which shows Athenian genealogy through a series of succession myths set in the remote past. She identifies the central panel above the door of the Parthenon as the pre-battle sacrifice of the daughter of the king Erechtheus, a sacrifice that ensured Athenian victory over Eumolpos and his Thracian army. The great procession marching toward the east end of the Parthenon shows the post-battle thanksgiving sacrifice of cattle and sheep, honey and water, followed by the triumphant army of Erechtheus returning from their victory. This represents the first Panathenaia set in mythical times, the model on which historic Panathenaic processions were based.[86][87] This interpretation has been rejected by William St Clair, who considers that the frieze shows the celebration of the birth of Ion, who was a descendant of Erechtheus.[88]

Pediments[edit]

Two pediments rise above the portals of the Parthenon, one on the east front, one on the west. The triangular sections once contained massive sculptures that, according to the second-century geographer Pausanias, recounted the birth of Athena and the mythological battle between Athena and Poseidon for control of Athens.[89]

East pediment[edit]

The east pediment originally contained 10 to 12 sculptures depicting the Birth of Athena. Most of those pieces were removed and lost during renovations in either the eighth or the twelfth century.[90] Only two corners remain today with figures depicting the passage of time over the course of a full day. Tethrippa of Helios is in the left corner and Selene is on the right. The horses of Helios’s chariot are shown with livid expressions as they ascend into the sky at the start of the day. Selene’s horses struggle to stay on the pediment scene as the day comes to an end.[91][92]

West pediment[edit]

The supporters of Athena are extensively illustrated at the back of the left chariot, while the defenders of Poseidon are shown trailing behind the right chariot. It is believed that the corners of the pediment are filled by Athenian water deities, such as the Kephisos river, the Ilissos river, and nymph Kallirhoe. This belief emerges from the fluid character of the sculptures’ body position which represents the effort of the artist to give the impression of a flowing river.[93][94] Next to the left river god, there are the sculptures of the mythical king of Athens (Cecrops or Kekrops) with his daughters ( Aglaurus, Pandrosos, Herse). The statue of Poseidon was the largest sculpture in the pediment until it broke into pieces during Francesco Morosini’s effort to remove it in 1688. The posterior piece of the torso was found by Lusieri in the groundwork of a Turkish house in 1801 and is currently held in the British Museum. The anterior portion was revealed by Ross in 1835 and is now held in the Acropolis Museum of Athens.[95]

Every statue on the west pediment has a fully completed back, which would have been impossible to see when the sculpture was on the temple; this indicates that the sculptors put great effort into accurately portraying the human body.[94]

Athena Parthenos[edit]

The only piece of sculpture from the Parthenon known to be from the hand of Phidias[96] was the statue of Athena housed in the naos. This massive chryselephantine sculpture is now lost and known only from copies, vase painting, gems, literary descriptions and coins.[97]

Later history[edit]

Late antiquity[edit]

A major fire broke out in the Parthenon shortly after the middle of the third century AD.[98][99] which destroyed the roof and much of the sanctuary’s interior.[100] Heruli pirates sacked Athens in 276, and destroyed most of the public buildings there, including the Parthenon.[101] Repairs were made in the fourth century AD, possibly during the reign of Julian the Apostate.[102] A new wooden roof overlaid with clay tiles was installed to cover the sanctuary. It sloped at a greater angle than the original roof and left the building’s wings exposed.[100]

The Parthenon survived as a temple dedicated to Athena for nearly 1,000 years until Theodosius II, during the Persecution of pagans in the late Roman Empire, decreed in 435 that all pagan temples in the Eastern Roman Empire be closed.[103] It is debated exactly when during the 5th century that the closure of the Parthenon as a temple was put into practice. It is suggested to have occurred in c. 481–484, on the order of Emperor Zeno, because the temple had been the focus of Pagan Hellenic opposition against Zeno in Athens in support of Illus, who had promised to restore Hellenic rites to the temples that were still standing.[104]

At some point in the fifth century, Athena’s great cult image was looted by one of the emperors and taken to Constantinople, where it was later destroyed, possibly during the siege and sack of Constantinople during the Fourth Crusade in 1204 AD.[105]

Christian church[edit]

The Parthenon was converted into a Christian church in the final decades of the fifth century[106] to become the Church of the Parthenos Maria (Virgin Mary) or the Church of the Theotokos (Mother of God). The orientation of the building was changed to face towards the east; the main entrance was placed at the building’s western end, and the Christian altar and iconostasis were situated towards the building’s eastern side adjacent to an apse built where the temple’s pronaos was formerly located.[107][108][109] A large central portal with surrounding side-doors was made in the wall dividing the cella, which became the church’s nave, and from the rear chamber, the church’s narthex.[107] The spaces between the columns of the opisthodomos and the peristyle were walled up, though a number of doorways still permitted access.[107] Icons were painted on the walls, and many Christian inscriptions were carved into the Parthenon’s columns.[102] These renovations inevitably led to the removal and dispersal of some of the sculptures.

The Parthenon became the fourth most important Christian pilgrimage destination in the Eastern Roman Empire after Constantinople, Ephesos, and Thessaloniki.[110] In 1018, the emperor Basil II went on a pilgrimage to Athens after his final victory over the First Bulgarian Empire for the sole purpose of worshipping at the Parthenon.[110] In medieval Greek accounts it is called the Temple of Theotokos Atheniotissa and often indirectly referred to as famous without explaining exactly which temple they were referring to, thus establishing that it was indeed well known.[110]

At the time of the Latin occupation, it became for about 250 years a Roman Catholic church of Our Lady. During this period a tower, used either as a watchtower or bell tower and containing a spiral staircase, was constructed at the southwest corner of the cella, and vaulted tombs were built beneath the Parthenon’s floor.[111]

The rediscovery of the Parthenon as an ancient monument dates back to the period of Humanism; Cyriacus of Ancona was the first after antiquity to describe the Parthenon, of which he had read many times in ancient texts. Thanks to him, Western Europe was able to have the first design of the monument, which Ciriaco called «temple of the goddess Athena», unlike previous travellers, who had called it «church of Virgin Mary»:[112]

…mirabile Palladis Divae marmoreum templum, divum quippe opus Phidiae («…the wonderful temple of the goddess Athena, a divine work of Phidias»).

Islamic mosque[edit]

In 1456, Ottoman Turkish forces invaded Athens and laid siege to a Florentine army defending the Acropolis until June 1458, when it surrendered to the Turks.[113] The Turks may have briefly restored the Parthenon to the Greek Orthodox Christians for continued use as a church.[114] Some time before the end of the fifteenth century, the Parthenon became a mosque.[115][116]

The precise circumstances under which the Turks appropriated it for use as a mosque are unclear; one account states that Mehmed II ordered its conversion as punishment for an Athenian plot against Ottoman rule.[117] The apse was repurposed into a mihrab,[118] the tower previously constructed during the Roman Catholic occupation of the Parthenon was extended upwards to become a minaret,[119] a minbar was installed,[107] the Christian altar and iconostasis were removed, and the walls were whitewashed to cover icons of Christian saints and other Christian imagery.[120]

Despite the alterations accompanying the Parthenon’s conversion into a church and subsequently a mosque, its structure had remained basically intact.[121] In 1667, the Turkish traveller Evliya Çelebi expressed marvel at the Parthenon’s sculptures and figuratively described the building as «like some impregnable fortress not made by human agency».[122] He composed a poetic supplication stating that, as «a work less of human hands than of Heaven itself, [it] should remain standing for all time».[123] The French artist Jacques Carrey in 1674 visited the Acropolis and sketched the Parthenon’s sculptural decorations.[124] Early in 1687, an engineer named Plantier sketched the Parthenon for the Frenchman Graviers d’Ortières.[100] These depictions, particularly Carrey’s, provide important, and sometimes the only, evidence of the condition of the Parthenon and its various sculptures prior to the devastation it suffered in late 1687 and the subsequent looting of its art objects.[124]

Destruction[edit]

As part of the Morean War (1684–1699), the Venetians sent an expedition led by Francesco Morosini to attack Athens and capture the Acropolis. The Ottoman Turks fortified the Acropolis and used the Parthenon as a gunpowder magazine – despite having been forewarned of the dangers of this use by the 1656 explosion that severely damaged the Propylaea – and as a shelter for members of the local Turkish community.[125]

On 26 September 1687 a Venetian mortar round, fired from the Hill of Philopappos, blew up the magazine.[102][126] The explosion blew out the building’s central portion and caused the cella’s walls to crumble into rubble.[121] According to Greek architect and archaeologist Kornilia Chatziaslani:[100]

…three of the sanctuary’s four walls nearly collapsed and three-fifths of the sculptures from the frieze fell. Nothing of the roof apparently remained in place. Six columns from the south side fell, eight from the north, as well as whatever remained from the eastern porch, except for one column. The columns brought down with them the enormous marble architraves, triglyphs, and metopes.

About three hundred people were killed in the explosion, which showered marble fragments over nearby Turkish defenders[125] and sparked fires that destroyed many homes.[100]

Accounts written at the time conflict over whether this destruction was deliberate or accidental; one such account, written by the German officer Sobievolski, states that a Turkish deserter revealed to Morosini the use to which the Turks had put the Parthenon; expecting that the Venetians would not target a building of such historic importance. Morosini was said to have responded by directing his artillery to aim at the Parthenon.[100][125] Subsequently, Morosini sought to loot sculptures from the ruin and caused further damage in the process. Sculptures of Poseidon and Athena’s horses fell to the ground and smashed as his soldiers tried to detach them from the building’s west pediment.[108][127]

In 1688 the Venetians abandoned Athens to avoid a confrontation with a large force the Turks had assembled at Chalcis; at that time, the Venetians had considered blowing up what remained of the Parthenon along with the rest of the Acropolis to deny its further use as a fortification to the Turks, but that idea was not pursued.[125]

Once the Turks had recaptured the Acropolis, they used some of the rubble produced by this explosion to erect a smaller mosque within the shell of the ruined Parthenon.[128] For the next century and a half, parts of the remaining structure were looted for building material and especially valuable objects.[129]

The 18th century was a period of Ottoman stagnation—so that many more Europeans found access to Athens, and the picturesque ruins of the Parthenon were much drawn and painted, spurring a rise in philhellenism and helping to arouse sympathy in Britain and France for Greek independence. Amongst those early travellers and archaeologists were James Stuart and Nicholas Revett, who were commissioned by the Society of Dilettanti to survey the ruins of classical Athens. They produced the first measured drawings of the Parthenon, published in 1787 in the second volume of Antiquities of Athens Measured and Delineated. In 1801, the British Ambassador at Constantinople, the Earl of Elgin, claimed that he obtained a firman (edict) from the kaymakam, whose existence or legitimacy has not been proved to this day, to make casts and drawings of the antiquities on the Acropolis, and to remove sculptures that were lying on the ground.[9]

Independent Greece[edit]

When independent Greece gained control of Athens in 1832, the visible section of the minaret was demolished; only its base and spiral staircase up to the level of the architrave remain intact.[130] Soon all the medieval and Ottoman buildings on the Acropolis were destroyed. The image of the small mosque within the Parthenon’s cella has been preserved in Joly de Lotbinière’s photograph, published in Lerebours’s Excursions Daguerriennes in 1842: the first photograph of the Acropolis.[131] The area became a historical precinct controlled by the Greek government. In the later 19th century, the Parthenon was widely considered by Americans and Europeans to be the pinnacle of human architectural achievement, and became a popular destination and subject of artists, including Frederic Edwin Church and Sanford Robinson Gifford.[132][133] Today it attracts millions of tourists every year, who travel up the path at the western end of the Acropolis, through the restored Propylaea, and up the Panathenaic Way to the Parthenon, which is surrounded by a low fence to prevent damage.[citation needed]

Dispute over the marbles[edit]

The dispute centres around those of the Parthenon Marbles removed by Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin, from 1801 to 1803, which are in the British Museum.[14] A few sculptures from the Parthenon are also in the Louvre in Paris, in Copenhagen, and elsewhere, while more than half are in the Acropolis Museum in Athens.[19][134] A few can still be seen on the building itself. The Greek government has campaigned since 1983 for the British Museum to return the sculptures to Greece.[134] The British Museum has consistently refused to return the sculptures,[135] and successive British governments have been unwilling to force the museum to do so (which would require legislation). Talks between senior representatives from Greek and British cultural ministries and their legal advisors took place in London on 4 May 2007. These were the first serious negotiations for several years, and there were hopes that the two sides might move a step closer to a resolution.[136]

In December 2022, the British newspaper The Guardian published a story with quotes from Greek government officials that suggested negotiations to return the marbles were underway and a «credible» solution was being discussed.[137]

Four pieces of the sculptures have been repatriated to Greece: 3 from the Vatican, and 1 from a museum in Sicily.[138]

Restoration[edit]

An organized effort to preserve and restore buildings on the Acropolis began in 1975, when the Greek government established the Committee for the Conservation of the Acropolis Monuments (ESMA). That group of interdisciplinary specialist scholars oversees the academic understanding of the site to guide restoration efforts.[139] The project later attracted funding and technical assistance from the European Union. An archaeological committee thoroughly documented every artefact remaining on the site, and architects assisted with computer models to determine their original locations. Particularly important and fragile sculptures were transferred to the Acropolis Museum.

A crane was installed for moving marble blocks; the crane was designed to fold away beneath the roofline when not in use.[140] In some cases, prior re-constructions were found to be incorrect. These were dismantled, and a careful process of restoration began.[141]

Originally, various blocks were held together by elongated iron H pins that were completely coated in lead, which protected the iron from corrosion. Stabilizing pins added in the 19th century were not so coated, and corroded. Since the corrosion product (rust) is expansive, the expansion caused further damage by cracking the marble.[142]

In 2019, Greece’s Central Archaeological Council approved a restoration of the interior cella’s north wall (along with parts of others). The project will reinstate as many as 360 ancient stones, and install 90 new pieces of Pentelic marble, minimizing the use of new material as much as possible. The eventual result of these restorations will be a partial restoration of some or most of each wall of the interior cella.[143]

See also[edit]

- Palermo Fragment

- Ancient Greek architecture

- List of Ancient Greek temples

- National Monument of Scotland, Edinburgh

- Walhalla temple Regensburg – Exterior modelled on the Parthenon, but the interior is a hall of fame for distinguished Germans

- Parthenon, Nashville – Full-scale replica

- Stripped Classicism

- Temple of Hephaestus

References[edit]

- ^ a b Parthenon Archived 5 March 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Academic.reed.edu. Retrieved on 4 September 2013.

- ^ a b The Parthenon Archived 2 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Ancientgreece.com. Retrieved on 4 September 2013.

- ^ Penprase, Bryan E. (2010). The Power of Stars: How Celestial Observations Have Shaped Civilization. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 221. ISBN 978-1-4419-6803-6. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- ^ Sakoulas, Thomas. «The Parthenon». Ancient-Greece.org. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

- ^ Wilson, Benjamin Franklin (1920). The Parthenon at Athens, Greece and at Nashville, Tennessee. Nashville, Tennessee: Stephen Hutcheson and the Online Distributed. Archived from the original on 6 June 2021. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Barletta, Barbara A. (2005). «The Architecture and Architects of the Classical Parthenon». In Jenifer Neils (ed.). The Parthenon: From Antiquity to the Present. Cambridge University Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-521-82093-6.

The Parthenon (Plate 1, Fig. 17) is probably the most celebrated of all Greek temples.

- ^ Sacks, David. «Parthenon.» Encyclopedia of the Ancient Greek World, David Sacks, Facts On File, 3rd edition, 2015. Accessed 15 July 2022.

- ^ Beard, Mary (2010). The Parthenon. Profile Books. p. 118. ISBN 978-1-84765-063-4.

- ^ a b c Titi, Catharine (2023). The Parthenon Marbles and International Law. pp. 42, 45. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-26357-6. ISBN 978-3-031-26356-9. S2CID 258846977.

- ^ a b Bury, J. B.; Meiggs, Russell (1956). A history of Greece to the death of Alexander the Great, 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 367–369.

- ^ Robertson, Miriam (1981). A Shorter History of Greek Art. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 90. ISBN 978-0-521-28084-6.

- ^ Davison, Claire Cullen; Lundgreen, Birte (2009). Pheidias:The Sculptures and Ancient Sources. Vol. 105. London: Institute of Classical Studies, University of London. p. 209. ISBN 978-1-905670-21-5. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ «Lord Elgin and the Parthenon Sculptures». British Museum. Archived from the original on 3 February 2013.

- ^ a b «How the Parthenon Lost Its Marbles». History Magazine. 28 March 2017. Archived from the original on 17 April 2019. Retrieved 17 April 2019.

- ^ «Reasons of Interventions». ysma.gr.

- ^ Magazine, Smithsonian. «Unlocking Mysteries of the Parthenon». Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 23 July 2022.

- ^ «Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, παρθεν-ών». www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 27 July 2022.

- ^ Hurwit 200, pp. 161–163.

- ^ a b «Parthenon». Encyclopædia Britannica.[edition needed]

- ^ Whitley, The Archaeology of Ancient Greece, p. 352.

- ^ François Queyrel, Le Parthénon. Un monument dans l’Histoire, Paris, Éditions Bartillat, 2020, pp. 199–200.

- ^ Hélène (4 March 2021). «Everlasting Glory in Athens». The Kosmos Society. Retrieved 10 July 2023.

- ^ a b «Harpocration, Valerius, Lexicon in decem oratores Atticos, λεττερ ε, ἙΚΑΤΟΜΠΕΔΟΝ». www.perseus.tufts.edu.

- ^ Demosthenes, Against Androtion 22.13 οἱ τὰ προπύλαια καὶ τὸν παρθενῶν᾽

- ^ Plutarch, Pericles 13.4.

- ^ van Rookhuijzen, Jan Z. (2020). «The Parthenon Treasury on the Acropolis of Athens». American Journal of Archaeology. 124 (1): 3–35. doi:10.3764/aja.124.1.0003. S2CID 213405037.

- ^ Kampouris, Nick (3 October 2021). «The Parthenon Has Had the Wrong Name for Centuries, Theory Claims». GreekReporter.com. Retrieved 24 July 2022.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica, 1878

- ^ Freely 2004, p. 69 Archived 17 November 2022 at the Wayback Machine «Some modern writers maintain that the Parthenon was converted into a Christian sanctuary during the reign of Justinian (527–565)…But there is no evidence to support this in the ancient sources. The existing evidence suggests that the Parthenon was converted into a Christian basilica in the last decade of the sixth century.»

- ^ a b Susan Deacy, Athena, Routledge, 2008, p. 111.

- ^ a b Burkert, Greek Religion, Blackwell, 1985, p. 143.

- ^ Joan Breton Connelly, Portrait of a Priestess: Women and Ritual in Ancient Greece

- ^ MC. Hellmann, L’Architecture grecque. Architecture religieuse et funéraire, Picard, 2006, p. 118.

- ^ a b B. Nagy, «Athenian Officials on the Parthenon Frieze», AJA, Vol. 96, No. 1 (January 1992), p. 55.

- ^ Thucydides 2.13.5. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- ^ S. Eddy, «The Gold in the Athena Parthenos», AJA, Vol. 81, No. 1 (Winter, 1977), pp. 107–111.

- ^ «Aristotle, Athenian Constitution, chapter 47». www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- ^ «Aristotle, Athenian Constitution, chapter 47 (Note 1)». www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- ^ B. Holtzmann and A. Pasquier, Histoire de l’art antique : l’art grec, École du Louvre, Réunion des musées nationaux, and Documentation française, 1998, p. 177.

- ^ Connelly, Joan Breton (2014). The Parthenon Enigma: a New Understanding of the West’s Most Iconic Building and the People Who Made It. New York: Vintage. ISBN 978-0-307-47659-3.

- ^ «Welcome to Joan Breton Connelly». Welcome to Joan Breton Connelly. Archived from the original on 21 September 2015. Retrieved 18 August 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Connelly, Joan Breton (28 January 2014). The Parthenon Enigma (1st ed.). New York: Knopf. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-307-59338-2.

- ^ Mendelsohn, Daniel (7 April 2014). «Deep Frieze». The New Yorker. ISSN 0028-792X. Retrieved 10 July 2023.

- ^ Beard, Mary. «The Latest Scheme for the Parthenon | Mary Beard». The New York Review of Books. ISSN 0028-7504. Retrieved 10 July 2023.

- ^ Beard, Mary; Hammond, Norman; Wuletich-Brinberg, Sybil; Wills, Garry; Green, Peter. «‘The Parthenon Enigma’—An Exchange | Peter Green». The New York Review of Books. ISSN 0028-7504. Retrieved 10 July 2023.

- ^ «Decoding the Parthenon by J.J. Pollitt». The New Criterion. Retrieved 18 August 2015.

- ^ «Rethinking the West’s Most Iconic Building». Bryn Mawr Alumnae Bulletin. Archived from the original on 8 September 2015. Retrieved 18 August 2015.

- ^ Spivey, Nigel (October 2014). «Art and Archaeology» (PDF). Greece & Rome. 61 (2): 287–290. doi:10.1017/S0017383514000138. S2CID 232181203.

- ^ Alexander, Caroline (23 January 2014). «If It Pleases the Gods». The New York Times (Review). ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 18 August 2015.

- ^ «Deep Frieze Meaning». The Weekly Standard. Retrieved 18 August 2015.

- ^ Ioanna Venieri. «Acropolis of Athens». Hellenic Ministry of Culture. Archived from the original on 24 October 2019. Retrieved 4 May 2007.

- ^ Hurwit 2005, p. 135

- ^ Herodotus Histories, 8.53

- ^ W. Dörpfeld, «Der aeltere Parthenon», Ath. Mitteilungen, XVII, 1892, pp. 158–189 and W. Dörpfeld, «Die Zeit des alteren Parthenon», AM 27, 1902, 379–416

- ^ P. Kavvadis, G. Kawerau, Die Ausgabung der Acropolis vom Jahre 1885 bis zum Jahre 1890, 1906.

- ^ NM Tod, A Selection of Greek Historical Inscriptions II, 1948, no. 204, lines 46–51, The authenticity of this is disputed, however; see also P. Siewert, Der Eid von Plataia (Munich 1972) 98–102

- ^ Kerr, Minott (23 October 1995). «‘The Sole Witness’: The Periclean Parthenon». Reed College Portland, Oregon, US. Archived from the original on 8 June 2007.

- ^ B. H. Hill, «The Older Parthenon», AJA, XVI, 1912, 535–558

- ^ B. Graef, E. Langlotz, Die Antiken Vasen von der Akropolis zu Athen, Berlin 1925–1933

- ^ W. Dinsmoor, «The Date of the Older Parthenon», AJA, XXXVIII, 1934, 408–448

- ^ W. Dörpfeld, «Parthenon I, II, III», AJA, XXXIX, 1935, 497–507, and W. Dinsmoor, AJA, XXXIX, 1935, 508–509

- ^ a b c Woodford, S. (2008). The Parthenon. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Singh, Ravi. «Acropolis Tickets». Retrieved 22 September 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ «Parthenon.» Britannica Library, Encyclopædia Britannica, 10 September 2021. Accessed 16 July 2022.

- ^ Senseney, John R. (2021). «The Architectural Origins of the Parthenon Frieze». Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. University of California Press. 80 (1): 12–29. doi:10.1525/jsah.2021.80.1.12. S2CID 233818539.

- ^ American Architect and Architecture. American Architect. 1892.

- ^ «LacusCurtius • Roman Architecture – Roof Tiles (Smith’s Dictionary, 1875)». penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- ^ John Julius Norwich, Great Architecture of the World, 2001, p. 63.

- ^ And in the surviving foundations of the preceding Older Parthenon (Penrose, Principles of Athenian Architecture 2nd ed. ch. II.3, plate 9).

- ^ «How Greek Temples Correct Visual Distortion – Architecture Revived». 15 October 2015.

- ^ Penrose op. cit. pp. 32–34, found the difference motivated by economies of labour; Gorham P. Stevens, «Concerning the Impressiveness of the Parthenon» American Journal of Archaeology 66.3 (July 1962: 337–338).

- ^ Archaeologists discuss similarly curved architecture and offer the theory. Nova, «Secrets of the Parthenon,» PBS. http://video.yahoo.com/watch/1849622/6070405[permanent dead link]

- ^ Hadingham, Evan (February 2008), Unlocking Mysteries of the Parthenon, Washington, DC: Smithsonian Magazine, p. 42

- ^ Van Mersbergen, Audrey M., «Rhetorical Prototypes in Architecture: Measuring the Acropolis,» Philosophical Polemic Communication Quarterly, Vol. 46, 1998.

- ^ George Markowsky (January 1992). «Misconceptions about the Golden Ratio» (PDF). The College Mathematics Journal. 23 (1). Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 April 2008. Retrieved 4 February 2008.

- ^ Livio, Mario (2003) [2002]. The Golden Ratio: The Story of Phi, the World’s Most Astonishing Number (First trade paperback ed.). New York City: Broadway Books. pp. 74–75. ISBN 0-7679-0816-3.

- ^ «Tarbell, F.B. A History of Ancient Greek Art. (online book)». Ellopos.net. Retrieved 18 April 2009.

- ^ Sideris, Athanasios (1 January 2004). «The Parthenon». Strolling Through Athens: 112–119.

- ^ «The Parthenon Frieze». Greek Ministry of Culture and Sports, Acropolis Museum, Acropolis Restoration Service. Retrieved 26 July 2022.

- ^ Harris, Beth; Zucker, Steven. «Parthenon (Acropolis)». Khan Academy. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- ^ Barringer, Judith M (2008). Art, myth, and ritual in classical Greece. Cambridge. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-521-64647-5. OCLC 174134120.

- ^ Pollini 2007, pp. 212–216; Brommer 1979, pp. 23, 30, pl. 41

- ^ Tenth metope from the south façade of the Parthenon, retrieved 30 January 2018

- ^ «Discovery Reveals Ancient Greek Theaters Used Moveable Stages Over 2,000 Years Ago». greece.greekreporter.com.

- ^ De la Croix, Horst; Tansey, Richard G.; Kirkpatrick, Diane (1991). Gardner’s Art Through the Ages (9th ed.). Thomson/Wadsworth. pp. 158–59. ISBN 0-15-503769-2.

- ^ Connelly, Parthenon and Parthenoi, 53–80.

- ^ Connelly, The Parthenon Enigma, chapters 4, 5, and 7.

- ^ St Clair, William (24 August 2022). Barnes, Lucy; St Clair, David (eds.). The Classical Parthenon: Recovering the Strangeness of the Ancient World. Open Book Publishers. doi:10.11647/obp.0279. ISBN 978-1-80064-344-4. S2CID 251787123.

- ^ «PAUSANIAS, DESCRIPTION OF GREECE 1.17–29 – Theoi Classical Texts Library». www.theoi.com. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- ^ Jeffrey M. Hurwit. «Helios Rising: The Sun, the Moon, and the Sea in the Sculptures of the Parthenon.» American Journal of Archaeology, vol. 121, no. 4, 2017, pp. 527–558. JSTOR, doi:10.3764/aja.121.4.0527. Accessed 22 July 2022.

- ^ «The Parthenon Sculptures by Mark Cartwright 2014». World History Encyclopedia.

- ^ «The British Museum: The Parthenon sculptures».

- ^ «Athenians and Eleusinians in the West Pediment of the Parthenon» (PDF).

- ^ a b «statue; pediment | British Museum». The British Museum.

- ^ Palagia, Olga (1998). The Pediments of the Parthenon by Olga Palagia. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-11198-1.

- ^ Lapatin, Kenneth D.S. (2001). Chryselephantine Statuary in the Ancient Mediterranean World. Oxford: OUP. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-19-815311-5.

- ^ N. Leipen, Athena Parthenos: a huge reconstruction, 1972.

- ^ «Introduction to the Parthenon Frieze». National Documentation Centre (Greek Ministry of Culture). Archived from the original on 28 October 2012. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- ^ Freely, John (23 July 2004). Strolling Through Athens: Fourteen Unforgettable Walks Through Europe’s Oldest City. I. B. Tauris. p. 69. ISBN 978-1-85043-595-2.

According to one authority, John Travlos, this occurred when Athens was sacked by the Heruli in AD 267, at which time the two-tiered colonnade in the cella was destroyed.

- ^ a b c d e f Chatziaslani, Kornilia. «Morosini in Athens». Archaeology of the City of Athens. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- ^ O’Donovan, Connell. «Pirates, marauders, and homos, oh my!». Retrieved 10 December 2015.

- ^ a b c «The Parthenon». Acropolis Restoration Service. Archived from the original on 28 August 2012. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- ^ Freely, John (23 July 2004). Strolling Through Athens: Fourteen Unforgettable Walks Through Europe’s Oldest City. I. B. Tauris. p. 69. ISBN 978-1-85043-595-2.

- ^ Trombley (1 May 2014). Hellenic Religion and Christianization c. 370-529, Volume I. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-27677-2.

- ^ Cremin, Aedeen (2007). Archaeologica. Frances Lincoln Ltd. p. 170. ISBN 978-0-7112-2822-1.

- ^ Stephenson, Paul (2022). New Rome: Empire in the East. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. p. 177. ISBN 9780674659629.

- ^ a b c d Freely, John (23 July 2004). Strolling Through Athens: Fourteen Unforgettable Walks Through Europe’s Oldest City. I. B. Tauris. p. 70. ISBN 978-1-85043-595-2.

- ^ a b Hollis, Edward (2009). The secret lives of buildings: from the ruins of the Parthenon to the Vegas Strip in thirteen stories. Internet Archive. New York, N.Y.: Metropolitan Books/Henry Holt. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-8050-8785-7.

- ^ Hurwit, Jeffrey M. (13 January 2000). The Athenian Acropolis: History, Mythology, and Archaeology from the Neolithic Era to the Present. CUP Archive. p. 293. ISBN 978-0-521-42834-7.

- ^ a b c Kaldellis, Anthony (2007). «A Heretical (Orthodox) History of the Parthenon» (PDF). University of Michigan. p. 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 August 2009.

- ^ Hurwit, Jeffrey M. (19 November 1999). The Athenian Acropolis: History, Mythology, and Archaeology from the Neolithic Era to the Present. CUP Archive. ISBN 9780521417860 – via Google Books.

- ^ E.W. Bodnar, Cyriacus of Ancona and Athens, Brussels-Berchem, 1960.

- ^ Babinger, Franz (1992). Mehmed the Conqueror and His Time. Princeton University Press. pp. 159–160. ISBN 978-0-691-01078-6.

- ^ Tomkinson, John L. «Ottoman Athens I: Early Ottoman Athens (1456–1689)». Anagnosis Books. Archived from the original on 29 July 2012. Retrieved 14 August 2012. «In 1466 the Parthenon was referred to as a church, so it seems likely that for some time at least, it continued to function as a cathedral, being restored to the use of the Greek archbishop.»

- ^ Tomkinson, John L. «Ottoman Athens I: Early Ottoman Athens (1456–1689)». Anagnosis Books. Archived from the original on 29 July 2012. Retrieved 14 August 2012. «Some time later – we do not know exactly when – the Parthenon was itself converted into a mosque.»

- ^ D’Ooge, Martin Luther (1909). The acropolis of Athens. Robarts – University of Toronto. New York: Macmillan. p. 317.

The conversion of the Parthenon into a mosque is first mentioned by another anonymous writer, the Paris Anonymous, whose manuscript dating from the latter half of the fifteenth century was discovered in the library of Paris in 1862.

- ^ Miller, Walter (1893). «A History of the Akropolis of Athens». The American Journal of Archaeology and of the History of the Fine Arts. 8 (4): 546–547. doi:10.2307/495887. JSTOR 495887.

- ^ Hollis, Edward (2009). The secret lives of buildings: from the ruins of the Parthenon to the Vegas Strip in thirteen stories. Internet Archive. New York, N.Y.: Metropolitan Books/Henry Holt. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-8050-8785-7.

- ^ Bruno, Vincent J. (1974). The Parthenon. W.W. Norton & Company. p. 172. ISBN 978-0-393-31440-3.

- ^ D’Ooge, Martin Luther (1909). The acropolis of Athens. Robarts — University of Toronto. New York: Macmillan. p. 317.

- ^ a b Fichner-Rathus, Lois (2012). Understanding Art (10 ed.). Cengage Learning. p. 305. ISBN 978-1-111-83695-5.

- ^ Stoneman, Richard (2004). A Traveller’s History of Athens. Interlink Books. p. 209. ISBN 978-1-56656-533-2.

- ^ Holt, Frank L. (November–December 2008). «I, Marble Maiden». Saudi Aramco World. 59 (6): 36–41. Archived from the original on 1 August 2012. Retrieved 3 December 2012.

- ^ a b T. Bowie, D. Thimme, The Carrey Drawings of the Parthenon Sculptures, 1971

- ^ a b c d Tomkinson, John L. «Venetian Athens: Venetian Interlude (1684–1689)». Anagnosis Books. Archived from the original on 4 October 2013. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- ^ Theodor E. Mommsen, The Venetians in Athens and the Destruction of the Parthenon in 1687, American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 45, No. 4 (October – December 1941), pp. 544–556

- ^ Palagia, Olga (1998). The Pediments of the Parthenon (2 ed.). Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-11198-1. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- ^ Tomkinson, John L. «Ottoman Athens II: Later Ottoman Athens (1689–1821)». Anagnosis Books. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- ^ Grafton, Anthony; Glenn W. Most; Salvatore Settis (2010). The Classical Tradition. Harvard University Press. p. 693. ISBN 978-0-674-03572-0.

- ^ Murray, John (1884). Handbook for travellers in Greece, Volume 2. Oxford University Press. p. 317.

- ^ Neils, The Parthenon: From Antiquity to the Present, 336– the picture was taken in October 1839

- ^ Carr, Gerald L. (1994). Frederic Edwin Church: Catalogue Raisonne of Works at Olana State Historic Site, Volume I. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 342–343. ISBN 978-0521385404.

- ^ «Collection: Ruins of the Parthenon». National Gallery of Art. Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- ^ a b Greek Premier Says New Acropolis Museum to Boost Bid for Parthenon Sculptures Archived 21 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine, International Herald Tribune

- ^ «The Parthenon sculptures: The Trustees’ statement». The British Museum. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- ^ «Talks held on Elgin Marbles row». 10 May 2007. Retrieved 10 July 2023.

- ^ Smith, Helena (3 December 2022). «Greece in ‘preliminary’ talks with British Museum about Parthenon marbles». The Observer.

- ^ «Pope returns Greece’s Parthenon Sculptures in ecumenical nod». ICT News. Associated Press. 16 December 2022. Retrieved 10 July 2023.

- ^ «Acropolis Restoration Service». YSMA. Retrieved 18 July 2022.

- ^ «Crane Shifts Masonry of Ancient Parthenon in Restoration Program». AP NEWS. Retrieved 14 May 2022.

- ^ «The Surface Conservation Project» (pdf file). Once they had been conserved, the West Frieze blocks were moved to the museum, and copies cast in artificial stone were reinstalled in their places.

- ^ Hadingham, Evan (2008). «Unlocking the Mysteries of the Parthenon». Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 22 February 2008.

- ^ Sakis, Ioannidis (5 May 2019). «Parthenon’s Inner Sanctum to be Restored». Greece Is. Retrieved 31 January 2022.

Sources[edit]

Printed sources[edit]

- Burkert, Walter (1985). Greek Religion. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-36281-9.

- Connelly, Joan Breton (1 January 1996). «Parthenon and Parthenoi: A Mythological Interpretation of the Parthenon Frieze» (PDF). American Journal of Archaeology. 100 (1): 53–80. doi:10.2307/506297. JSTOR 506297. S2CID 41120274. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 August 2018.

- Connelly, Joan Breton (2014). The Parthenon Enigma: A New Understanding of the West’s Most Iconic Building and the People who Made It. Random House. ISBN 978-0-307-47659-3.

- D’Ooge, Martin Luther (1909). The Acropolis of Athens. Macmillan.

- Frazer, Sir James George (1998). «The King of the Woods». The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-283541-3.

- Freely, John (2004). Strolling Through Athens: Fourteen Unforgettable Walks through Europe’s Oldest City (2 ed.). Tauris Parke Paperbacks. ISBN 978-1-85043-595-2.

- Hollis, Edward (2009). The Secret Lives of Buildings: From the Ruins of the Parthenon to the Vegas Strip in Thirteen Stories. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-8050-8785-7.

- Hurwit, Jeffrey M. (2000). The Athenian Acropolis: History, Mythology, and Archeology from the Neolithic Era to the Present. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-42834-7.

- Hurwit, Jeffrey M. (2005). «The Parthenon and the Temple of Zeus at Olympia». In Judith M. Barringer; Jeffrey M. Hurwit; Jerome Jordan Pollitt (eds.). Periklean Athens and Its Legacy: Problems and Perspectives. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-70622-4.

- Neils, Jenifer (2005). The Parthenon: From Antiquity to the Present. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-82093-6.

- «Parthenon». Encyclopædia Britannica. 2002.

- Pelling, Christopher (1997). «Tragedy and Religion: Constructs and Readings». Greek Tragedy and the Historian. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-814987-3.

- Tarbell, F.B. A History of Ancient Greek Art.

- Whitley, James (2001). «The Archaeology of Democracy: Classical Athens». The Archaeology of Ancient Greece. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-62733-7.

Online sources[edit]

- «Greek Premier Says New Acropolis Museum to Boost Bid for Parthenon Sculptures». International Herald Tribune. 9 October 2006. Archived from the original on 21 February 2007. Retrieved 23 April 2007.

- «Parthenon». Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 5 May 2007.

- Ioanna Venieri. «Acropolis of Athens – History». Acropolis of Athens. Οδυσσεύς. Archived from the original on 24 October 2019. Retrieved 4 May 2007.

- Nova – PBS. «Secrets of the Parthenon – History». Acropolis of Athens. PBS. Retrieved 14 October 2010.

Further reading[edit]

- Beard, Mary. The Parthenon. Harvard University: 2003. ISBN 0-674-01085-X.

- Vinzenz Brinkmann (ed.): Athen. Triumph der Bilder. Exhibition catalogue Liebieghaus Skulpturensammlung, Frankfurt, 2016, ISBN 978-3-7319-0300-0.

- Connelly, Joan Breton Connelly. «The Parthenon Enigma: A New Understanding of the West’s Most Iconic Building and the People Who Made It.» Archived 28 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine Knopf: 2014. ISBN 0-307-47659-6.

- Cosmopoulos, Michael (editor). The Parthenon and its Sculptures. Cambridge University: 2004. ISBN 0-521-83673-5.

- Holtzman, Bernard (2003). L’Acropole d’Athènes : Monuments, Cultes et Histoire du sanctuaire d’Athèna Polias (in French). Paris: Picard. ISBN 978-2-7084-0687-2.

- King, Dorothy «The Elgin Marbles» Hutchinson / Random House, 2006. ISBN 0-09-180013-7

- Osada, T. (ed.) The Parthenon Frieze. The Ritual Communication between the Goddess and the Polis. Parthenon Project Japan 2011–2014 Phoibos Verlag, Wien 2016, ISBN 978-3-85161-124-3.

- Queyrel, François (2008). Le Parthénon: un monument dans l’histoire. Bartillat. ISBN 978-2-84100-435-5..

- Papachatzis, Nikolaos D. Pausaniou Ellados Periegesis – Attika Athens, 1974.

- Tournikio, Panayotis. Parthenon. Abrams: 1996. ISBN 0-8109-6314-0.

- Traulos, Ioannis N. I Poleodomike ekselikses ton Athinon Athens, 1960 ISBN 960-7254-01-5

- Woodford, Susan. The Parthenon. Cambridge University, 1981. ISBN 0-521-22629-5

- Catharine Titi, The Parthenon Marbles and International Law, Springer, 2023, ISBN 978-3-031-26356-9.

External links[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Parthenon.

Look up parthenon in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

- The Acropolis of Athens: The Parthenon Archived 18 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine (official site with a schedule of its opening hours, tickets, and contact information)

- (Hellenic Ministry of Culture) The Acropolis Restoration Project Archived 24 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- (Hellenic Ministry of Culture) The Parthenon Frieze (in Greek)

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre – Acropolis, Athens

- Metropolitan Government of Nashville and Davidson County – The Parthenon Archived 28 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- The Athenian Acropolis by Livio C. Stecchini (Takes the heterodox view of the date of the proto-Parthenon, but a useful summary of the scholarship.)

- The Friends of the Acropolis

- Illustrated Parthenon Marbles – Janice Siegel, Department of Classics, Hampden–Sydney College, Virginia

- Parthenon:description, photo album

- View a digital reconstruction of the Parthenon in virtual reality from Sketchfab

Videos[edit]

- A Wikimedia video of the main sights of the Athenian Acropolis

- Secrets of the Parthenon video by Public Broadcasting Service, on YouTube

- Parthenon by Costas Gavras

- The history of Acropolis and Parthenon from the Greek tv show Η Μηχανή του Χρόνου (Time machine) (in Greek), on YouTube

- The Acropolis of Athens in ancient Greece – Dimensions and proportions of Parthenon on Youtube

- Institute for Advanced Study: The Parthenon Sculptures

Все словари русского языка: Толковый словарь, Словарь синонимов, Словарь антонимов, Энциклопедический словарь, Академический словарь, Словарь существительных, Поговорки, Словарь русского арго, Орфографический словарь, Словарь ударений, Трудности произношения и ударения, Формы слов, Синонимы, Тезаурус русской деловой лексики, Морфемно-орфографический словарь, Этимология, Этимологический словарь, Грамматический словарь, Идеография, Пословицы и поговорки, Этимологический словарь русского языка.

фидий

Энциклопедический словарь

Фи́дий (начало V в. до н. э. — около 432-431 до н. э.), древнегреческий скульптор периода высокой классики. Главный помощник Перикла при реконструкции Акрополя в Афинах. Грандиозные статуи — Афины Промахос на Акрополе (бронза, около 460 до н. э.), Зевса Олимпийского и Афины Парфенос (обе — золото, слоновая кость) — не сохранились. Под руководством Фидия исполнено скульптурное убранство Парфенона. Творчество Фидия — одно из высших достижений мирового искусства, его образы сочетают жизненность с возвышенной классической гармонией и красотой.

* * *

ФИДИЙ — ФИ́ДИЙ (нач. 5 в. до н. э. — ок. 432-431 до н. э.), древнегреческий скульптор периода высокой классики. Главный помощник Перикла (см. ПЕРИКЛ) при реконструкции Акрополя в Афинах (см. АКРОПОЛЬ). Грандиозные статуи — Афины Промахос на Акрополе (бронза, ок. 460 до н. э.), Зевса Олимпийского и Афины Парфенос (см. АФИНА Парфенос) (обе — золото, слоновая кость) — не сохранились. Статуя Зевса для храма в Олимпии — одно из Семи чудес древнего мира. Образы Фидия возвышены и прекррасны, соразмерны человеку, но и близки к представлению о божествах, справедливых, могучих, идеально красивых.

оводством Фидия исполнено скульптурное убранство Парфенона (см. ПАРФЕНОН) (фризы и фронтонные группы).

Творчество Фидия — одно из высших достижений мирового искусства, его образы сочетают жизненность с возвышенной классической гармонией и красотой.

Большой энциклопедический словарь

ФИДИЙ (нач. 5 в. до н. э. — ок. 432-431 до н. э.) — древнегреческий скульптор периода высокой классики. Главный помощник Перикла при реконструкции Акрополя в Афинах. Грандиозные статуи — Афины Промахос на Акрополе (бронза, ок. 460 до н. э.), Зевса Олимпийского и Афины Парфенос (обе — золото, слоновая кость) — не сохранились. Под руководством Фидия исполнено скульптурное убранство Парфенона. Творчество Фидия — одно из высших достижений мирового искусства, его образы сочетают жизненность с возвышенной классической гармонией и красотой.

Энциклопедия Кольера

ФИДИЙ (р. ок. 490 до н.э.), древнегреческий скульптор, которого многие считают величайшим художником древности. Фидий был уроженцем Афин, его отца звали Хармидом. Мастерству скульптора Фидий учился в Афинах в школе Гегия и в Аргосе в школе Агелада (в последней, возможно, одновременно с Поликлетом). Среди существующих ныне статуй нет ни одной, которая бы несомненно принадлежала Фидию. Наши знания о его творчестве основаны на описаниях античных авторов, на изучении поздних копий, а также сохранившихся работ, которые с большей или меньшей достоверностью приписываются Фидию. Среди ранних работ Фидия, созданных ок. 470-450 до н.э., следует назвать культовую статую Афины Ареи в Платеях, сделанную из позолоченного дерева (одежда) и пентелийского мрамора (лицо, руки и ноги). К тому же периоду, ок. 460 до н.э., относится мемориальный комплекс в Дельфах, сооруженный в честь победы афинян над персами в Марафонской битве. Тогда же (ок. 456 до н.э.), и тоже на средства от добычи, захваченной в Марафонской битве, Фидий установил на Акрополе колоссальную бронзовую статую Афины Промахос (Заступницы). Другая бронзовая статуя Афины на Акрополе, т.н. Афина Лемния, которая держит шлем в руке, была создана Фидием ок. 450 до н.э. по заказу аттических колонистов, отплывавших на остров Лемнос. Возможно, две статуи, находящиеся в Дрездене, а также голова Афины из Болоньи являются ее копиями. Хрисоэлефантинная (из золота и слоновой кости) статуя Зевса в Олимпии считалась в древности шедевром Фидия. У Диона Хрисостома и Квинтилиана (1 в. н.э.) говорится, что благодаря непревзойденной красоте и богоугодности творения Фидия обогатилась сама религия, а Дион добавляет, что всякий, кому довелось увидеть эту статую, забывает все свои печали и невзгоды. Подробное описание статуи, считавшейся одним из семи чудес света, имеется у Павсания. Зевс был изображен сидящим. На ладони правой его руки стояла богиня Ника, а в левой он держал скипетр, наверху которого сидел орел. Зевс был бородатым и длинноволосым, с лавровым венком на голове. Сидящая фигура едва не касалась потолка головой, так что возникало впечатление, что если Зевс встанет, то снесет с храма крышу. Трон был богато украшен золотом, слоновой костью и драгоценными камнями. В верхней части трона над головой статуи помещались с одной стороны фигуры трех Харит, а с другой — трех времен года (Ор); на ножках трона были изображены танцующие Ники. На перекладинах между ножками трона стояли статуи, представлявшие олимпийские состязания и битву греков (возглавляемых Гераклом и Тесеем) с амазонками. Выполненный из черного камня пьедестал трона украшали золотые рельефы, на которых были изображены боги, в частности Эрот, который встречает выходящую из морских волн Афродиту, и увенчивающая ее венком Пейто (богиня убеждения). Статуя Зевса Олимпийского или одна его голова изображались на монетах, которые чеканились в Элиде. Относительно времени создания статуи ясности не было уже в античности, но, поскольку строительство храма было завершено ок. 456 до н.э., вероятнее всего, статуя была поставлена не позднее ок. 450 до н.э. (теперь возобновились попытки отнести Зевса из Олимпии ко времени после Афины Парфенос). Когда Перикл развернул в Афинах широкое строительство, Фидий возглавил все работы на Акрополе, среди прочего и возведение Парфенона, которое вели архитекторы Иктин и Калликрат в 447-438 до н.э. Парфенон, храм богини-покровительницы города Афины, одно из наиболее прославленных созданий античной архитектуры, представлял собой дорический периптер. Обильное пластическое убранство храма выполнила большая группа скульпторов, работавшая под началом Фидия и, вероятно, по его эскизам (наиболее знамениты находящиеся теперь в Британском музее рельефные фризы Парфенона и фрагментарно сохранившиеся статуи с фронтонов). Стоявшую в храме культовую хрисоэлефантинную статую Афины Парфенос, которая была закончена в 438 до н.э., изваял сам Фидий. Описание Павсания и многочисленные копии дают о ней достаточно ясное представление. Афина изображалась стоящей в полный рост, на ней был длинный, свисавшей тяжелыми складками хитон. На ладони правой руки Афины стояла крылатая богиня Ника; на груди Афины была эгида с головой Медузы; в левой руке богиня держала копье, а к ее ногам был прислонен щит. Около копья свернулась священная змея Афины (Павсаний называет ее Эрихтонием). На постаменте статуи было изображено рождение Пандоры (первой женщины). Как пишет Плиний Старший, на внешней стороне щита была вычеканена битва с амазонками, на внутренней — борьба богов с гигантами, а на сандалиях Афины имелось изображение кентавромахии. На голове богини был шлем, увенчанный тремя гребнями, средний из которых представлял собой сфинкса, а боковые грифонов. У Афины имелись украшения: ожерелья, серьги, браслеты. Близость стиля со скульптурами и рельефами Парфенона чувствуется в статуях Деметры (ее копии находятся в Берлине и Шершеле, Алжир) и Коры (копия на вилле Альбани). Мотивы обеих статуй использованы в знаменитом большом вотивном рельефе из Элевсина (Афины, Археологический музей), римская копия которого имеется в музее Метрополитен в Нью-Йорке. Складки одеяния Коры близки по стилю драпировкам статуи стоящего Зевса, копия которой хранится в Дрездене, а торс, возможно, являющийся фрагментом оригинала, — в Олимпии. К фризу Парфенона близок по стилю Анадумен (юноша, завязывающий повязку вокруг головы); возможно, она была создана в качестве ответа Диадумену Поликлета. Статуя Фидия гораздо естественнее в смысле позы и жеста, но несколько грубее. Вместе с Поликлетом и Кресилаем Фидий принимал участие в конкурсе на статую раненной амазонки для храма Артемиды в Эфесе и занял второе место после Поликлета; копией с его статуи считается т.н. Амазонка Маттеи (Ватикан). Раненная в бедро, амазонка заткнула хитон за пояс; чтобы уменьшить боль, она опирается на копье, ухватившись за него обеими руками, причем правая поднята выше головы. Как и в случае Афины Парфенос и рельефов Парфенона, богатое содержание помещено здесь в простую форму. Творения Фидия грандиозны, величественны и гармоничны; форма и содержание находятся в них в совершенном равновесии. Ученики мастера, Алкамен и Агоракрит, продолжали работать в его стиле в последней четверти 5 в. до н.э., а многие другие скульпторы, среди них Кефисодот, — и в первой четверти 4 в. до н.э.

ЛИТЕРАТУРА

Нюберг С. Фидий. М., 1941

Иллюстрированный энциклопедический словарь

Фидий или кpуг Фидия. «Мойpы». Фpагмент скульптуpы восточного фpонтона Паpфенона в Афинах. Мpамоp. 438-432 до н.э. Британский музей. Лондон.

ФИДИЙ (начало 5 в. до нашей эры — около 432 — 431 до нашей эры), древнегреческий скульптор. Главный помощник Перикла при реконструкции Акрополя в Афинах. Грандиозные статуи — Афины Промахос на Акрополе (бронза, около 460 до нашей эры, Зевса Олимпийского и Афины Парфенос (обе — золото, слоновая кость) — не сохранились. Под руководством Фидия исполнено скульптурное убранство Парфенона. Творчество Фидия — одно из высших достижений мирового искусства, его образы сочетают жизненность с возвышенной классической гармонией и совершенной красотой.

Грамматический словарь

Словарь древнегреческих имен

Фидий

(ок. 490-ок. 415 до н. э.)

Афинский ваятель. Автор скульптур из бронзы, кости с золотом и мрамора. До нас дошли оригинальные скульптуры Фидия или выполненные под руководством скульптора его учениками, — мраморные фигуры из афинского Парфенона (Элджинские мраморы). Уцелели также копии некоторых работ Фидия — например, статуи девы Афины. К сожалению, почти невозможно себе представить, какой была знаменитая статуя Зевса работы Фидия, которую Павсаний видел в Олимпии: она сгорела в Константинополе во время пожара 475. Не сохранилось также копий Фидиевой Афины Промахос (Победительницы), стоявшей на пропилеях Акрополя (ее высота достигала 17 м), однако копии статуи Афины, находившейся на острове Лемносе, дошли до наших дней (одна из них сейчас находится в Дрездене). Известно, что в 432 Фидий был изгнан из Афин политическими противниками Перикла, и, возможно, умер он в ссылке.

Сканворды для слова фидий

— Отец Архимеда.

— Древнегреческий скульптор, архитектор, главный помощник Перикла при реконструкции Акрополя в Афинах, автор статуи Афина Промахос на Акрополе, Зевс Олимпийский и Афина Парфенос, скульптурного убранства Парфенона.

— Он создал одно из чудес света — статую Зевса в Афинах.

— Плутарх утверждает, что этот человек включил самого себя в число персонажей композиции, изображающей битву с амазонками — в храме Парфенон.

Полезные сервисы

Парфенон.

Парфенон

выстроен в дорическом ордере, каждая

из окружающих его

колонн стоит непосредственно без базы,

на плоскости стилобата, имеет

каннелюры с острыми ребрами и венчается

капителью, включающей

эхин и абаку. Над колоннадой размещена

несомая часть здания — антаблемент,

состоящий из архитрава — балки, лежащей

на капителях, фриза,

разделенного на триглифы и метопы,

украшенные рельефами, и карниза.

В центре огромных для божества ступеней

восточной и западной

сторон сделаны невысокие ступени для

входа в храм человека. За торцовыми

колоннами расположена вторая колоннада,

образующая про-наос

— преддверие храма. Высокие стены

ограничивают внутреннее убранство

здания. За высокой дверью открывалась

целла, или наос,— основное

пространство с двухъярусной колоннадой,