Подготовлены редакции документа с изменениями, не вступившими в силу

(в ред. Федерального закона от 07.12.2011 N 420-ФЗ)

(см. текст в предыдущей редакции)

Дискриминация, то есть нарушение прав, свобод и законных интересов человека и гражданина в зависимости от его пола, расы, национальности, языка, происхождения, имущественного и должностного положения, места жительства, отношения к религии, убеждений, принадлежности к общественным объединениям или каким-либо социальным группам, совершенное лицом с использованием своего служебного положения, —

наказывается штрафом в размере от ста тысяч до трехсот тысяч рублей или в размере заработной платы или иного дохода осужденного за период от одного года до двух лет, либо лишением права занимать определенные должности или заниматься определенной деятельностью на срок до пяти лет, либо обязательными работами на срок до четырехсот восьмидесяти часов, либо исправительными работами на срок до двух лет, либо принудительными работами на срок до пяти лет, либо лишением свободы на тот же срок.

|

|

This article needs to be updated. Please help update this article to reflect recent events or newly available information. (November 2022) |

Russia has consistently been criticized by international organizations and independent domestic media outlets for human rights violations.[1][2][3] Some of the most commonly cited violations include deaths in custody,[4] the systemic and widespread use of torture by security forces and prison guards,[5][6][7][8][9][10] the existence of hazing rituals within the Russian Army —referred to as dedovshchina («reign of grandfathers»)— as well as prevalent breaches of children’s rights, instances of violence and prejudice against ethnic minorities,[11][12] and the targeted killings of journalists.[13][14]

As the successor state to the Soviet Union, the Russian Federation is beholden to the same human rights agreements that were signed and ratified by its predecessor, such as the international covenants on civil and political rights as well as economic, social, and cultural rights.[15] In the late 1990s, Russia also ratified the European Convention on Human Rights (with reservations), and from 1998 onwards the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg became a last court of appeal for Russian citizens from their national system of justice. According to Chapter 1, Article 15 of the 1993 Constitution, these embodiments of international law take precedence over national federal legislation.[note 1][16][17]

As a former member of the Council of Europe and a signatory of the European Convention on Human Rights, Russia carried international obligations related to the issue of human rights.[18] In the introduction to the 2004 report on the situation in Russia, the Commissioner for Human Rights of the Council of Europe noted the «sweeping changes since the collapse of the Soviet Union undeniable».[19]

However, starting from Vladimir Putin’s second presidential term (2004–2008), there were increasing reports of human rights violations. Following the 2011 State Duma elections and Putin’s subsequent return to the presidency in spring 2012, there has been a legislative onslaught on many international and constitutional rights, e.g. Article 20 (Freedom of Assembly and Association) of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which is embodied in Articles 30 and 31 of the Constitution of the Russian Federation (1993). In December 2015, a law was enacted that empowers the Constitutional Court of Russia to determine the enforceability or disregard of resolutions from intergovernmental bodies, such as the European Court of Human Rights.[20] As of 16 March 2022, Russia is no longer a member state of the Council of Europe.

Background[edit]

|

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (August 2020) |

Human rights were severely restricted within the Soviet Union. From 1927 to 1953, it operated as a totalitarian regime, and until 1990, as a single-party state. The government commonly silenced freedom of speech and used harsh measures against any dissent. Any independent political efforts, including labor unions, private businesses, churches, and opposing political parties, were not tolerated. Citizens’ movement was strictly controlled both within the country and internationally, and private property rights were heavily limited.

In practice, the Soviet government significantly curtailed many of the principles of the rule of law, civil liberties, legal protections, and property rights, considering them representative of «bourgeois morality,» according to Soviet legal thinker Andrey Vyshinsky. Despite officially signing human rights agreements, like the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights in 1973, these documents were mostly unknown and unavailable to people living under Communist rule. Furthermore, the Communist authorities showed little respect for these commitments. Human rights activists in the Soviet Union consistently faced harassment, suppression, and arrest.

The Putin presidency[edit]

Ratings[edit]

During Putin’s first term as President (2000–2004), Freedom House rated Russia as «partially free» with poor scores of 4 on both political rights and civil liberties (1 being most free, and 7 least free). In the period from 2005 to 2008, Freedom House rated Russia as «not free» with scores of 6 for political rights and 5 for civil liberties according to its Freedom in the World reports.[21]

In 2006, The Economist published a democracy rating, which placed Russia at 102nd among 167 countries and defined it as a «hybrid regime with a trend towards curtailment of media and other civil liberties».[22]

According to the Human Rights Watch 2016 report, the human rights situation in the Russian Federation continues to deteriorate.[23]

By 2016, four years into Putin’s third term as president, the Russian Federation had sunk further on the Freedom House rating:[24]

[T]he Kremlin continued a crackdown on civil society, ramping up pressure on domestic nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and branding the U.S.-based National Endowment for Democracy and two groups backed by billionaire philanthropist George Soros as ‘undesirable organizations’. The regime also intensified its tight grip on the media, saturating the information landscape with nationalist propaganda while suppressing the most popular alternative voices.

Reportedly in 2019, with France and Germany’s constant efforts in saving Moscow from being expelled from the Europe’s human rights watchdog, Russia might retain its seat if it resumes its membership fees payment.[25]

Overview of issues[edit]

International monitors and domestic observers have listed numerous, often deeply-rooted problems in the country and, with their advocacy, citizens have directed a flood of complaints to the European Court of Human Rights since 1998. By 1 June 2007, 22.5% of its pending cases were complaints against the Russian Federation by its citizens.[26] This proportion had risen steadily since 2002 as in 2006 there were 151 admissible applications against Russia (out of 1,634 for all the countries) while in 2005 it was 110 (of 1,036), in 2004 it was 64 (of 830), in 2003 it was 15 (of 753) and in 2002 it was 12 (of 578).[27][28][29]

Chechnya posed a separate problem and during the Second Chechen War, which lasted from September 1999 to 2005, there were numerous instances of summary execution and forced disappearance of civilians there.[30][31][32] According to the ombudsman of the Chechen Republic, Nurdi Nukhazhiyev, the most complex and painful problem as of March 2007 was to trace over 2,700 abducted and forcefully held citizens; analysis of the complaints of citizens of Chechnya shows that social problems were ever more frequently coming to the foreground; two years earlier, he said, complaints mostly concerned violations of the right to life.[33]

NGOs[edit]

The Federal Law of 10 January 2006 changed the rules affecting registration and operation of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) in Russia.[34][35][36] The Russian-Chechen Friendship Society, among others, was closed.[37] A detailed report by Olga Gnezdilova demonstrated that small, genuinely volunteer organisations were disproportionately hit by the demands of the new procedures: for the time being, larger NGOs with substantial funding were not affected.[38]

Following Putin’s re-election in May 2012 for a third term as president, a new Federal Law was passed, requiring all NGOs in receipt of foreign funding and «engaged in political activities» to register as «foreign agents» with the RF Ministry of Justice. By September 2016 144 NGOs were listed on the Register, including many of the oldest, most well-known and respected organisations, both internationally and domestically.[39]

Government can brand NGOs as «undesirable» to fine and shut them down. Members of «undesirable organisations» can be fined and imprisoned.[23]

These restrictive policies (Russian funders were also deterred) were a denial of the Freedom of Association embodied in Article 30 of the 1993 Constitution of the Russian Federation.[citation needed]

Assassinations[edit]

The deepest concern was reserved for the periodic unsolved assassinations of leading opposition politicians, lawmakers, journalists, and critics of the government, at home and sometimes abroad. According to a BuzzFeed News report in 2017, current and former US and UK intelligence agents told the outlet that they believe that Russian assassins, possibly on government orders, could be linked to 14 deaths on British soil that were dismissed as not suspicious by police.[40]

In 1998, human rights advocate Galina Starovoitova was shot dead in St. Petersburg at the entrance of her apartment.[41] In 2003, Yuri Schekochikhin mysteriously died from illness, causing speculation into his death, such as poisoning.[42] In 2003, the liberal politician Sergei Yushenkov was shot dead.[43] In 2006, Alexander Litvinenko was poisoned with polonium and died. A British inquiry concluded that President Putin had «probably» approved his murder.[44] In 2006, investigative journalist Anna Politkovskaya was shot dead.[45] In 2009, human rights advocate Stanislav Markelov and journalist Anastasia Baburova were shot dead in Moscow. In 2015, opposition politician Boris Nemtsov was shot dead near the Kremlin.[46] In 2017, journalist Nikolay Andrushchenko was beaten to death.[47]

The only deaths, in the view of Russian observers, to be convincingly investigated and successfully prosecuted, were the 2010 killings of Markelov and Baburova and the 2004 murder of anthropologist Nikolai Girenko, both the work of right-wing extremists. The perpetrators of certain other killings have been charged and convicted: since 1999 none of the instigators, the men who ordered the killing, have been identified or brought to justice.[citation needed]

Political prisoners[edit]

The right to a fair trial and freedom from political or religious persecution has been violated ever more frequently over the past decade.[clarification needed]

The numbers reliably considered to be political prisoners have risen sharply in the last four years. In May 2016, the Memorial Human Rights Centre put the total at 89.[48] By May 2017, Memorial considered there were at least 117 political prisoners or prisoners of conscience (66 accused of belonging to the Muslim organisation Hizb ut-Tahrir al-Islami which has been banned in Russia since 2010). Among these prisoners is also human rights defender Emir-Usein Kuku from Crimea who was accused of belonging to Hizb ut-Tahrir although he denies any involvement in this organization. Amnesty International has called for his immediate liberation.[49][50]

At various times those imprisoned have included human rights defenders, journalists like Mikhail Trepashkin,[51] and scientists such as Valentin Danilov.[52] Since 2007, loosely-worded laws against «extremism» or «terrorism» have been used to incarcerate the often youthful activists who have protested in support of freedom of assembly, against the alleged mass falsification of elections in 2011 and, since 2014, against the occupation of Crimea, the conflict in eastern Ukraine and corruption in the highest echelons of the government and State. Political prisoners are often subjected to torture in prisons and penal colonies.[53][4][54][55][56]

On 10 May 2014, Ukrainian filmmaker Oleg Sentsov was arrested in Simferopol, Crimea. He was taken to Russia, where he was sentenced to 20 years in prison for alleged terrorist activities. Amnesty International considered the trial unfair and called for the release of Sentsov.[57] Human Rights Watch described the trial as a political show trial calling for the liberation of the filmmaker.[58] On 7 September 2019 Sentsov was released in a prisoner swap.[59]

In May 2018 Server Mustafayev, the founder and coordinator of the human rights movement Crimean Solidarity was imprisoned by Russian authorities and charged with «membership of a terrorist organisation». Amnesty International and Front Line Defenders demand his immediate release.[60][61]

There were cases of attacks on demonstrators organized by local authorities.[62]

With the passing of time some of these prisoners have been released or, like Igor Sutyagin, exchanged with other countries for Russian agents held abroad. Nevertheless, the numbers continue to mount. According to some organisations there are now more than 300 individuals who have either been sentenced to terms of imprisonment in Russia, or are currently detained awaiting trial (in custody or under home arrest), or have fled abroad or gone into hiding, because of persecution for their beliefs and their attempts to exercise their rights under the Russian Constitution and international agreements.[63]

In April 2019, an Israeli citizen who carried 9.6 grams of hashish was detained in Russia and sentenced to more than seven years in prison in October 2019. This sentence had political reasons.[64] She was pardoned in January 2020.[65]

On 22 June 2020, Human Rights Organization along with Amnesty International wrote a joint-letter to the Prosecutor General of the Russian Federation, Igor Viktorovich Krasnov. In their letter, they asked for the release of six human rights defender who were convicted and sentenced in November 2019 to prison terms ranging from seven to 19 years on groundless terror-related charges.[66]

On 17 January 2021, Amnesty International declared Alexei Navalny to be a prisoner of conscience following his detention after returning to Russia and called on the Russian authorities to release him.[67]

As of June 2020, per Memorial Human Rights Center, there were 380 political prisoners in Russia, including 63 individuals prosecuted, directly or indirectly, for political activities (including Alexey Navalny) and 245 prosecuted for their involvement with one of the Muslim organizations that are banned in Russia. 78 individuals on the list, i.e. more than 20% of the total, are residents of Crimea.[68][69]

Russia has been accused of hostage diplomacy and has exchanged prisoners with the United States.[70]

On 4 March 2022, Russian President Vladimir Putin signed into law a bill introducing prison sentences of up to 15 years for those who publish «knowingly false information» about the Russian armed forces and their operations, leading to some media outlets in Russia to stop reporting on Ukraine or shutting their media outlet.[71] As of December 2022, more than 4,000 people were prosecuted under «fake news» laws in connection with the war in Ukraine.[72]

Judicial system[edit]

The judiciary of Russia is subject to manipulation by political authorities according to Amnesty International.[1][73] According to Constitution of Russia, top judges are appointed by the Federation Council, following nomination by the President of Russia.[74] Anna Politkovskaya described in her book Putin’s Russia stories of judges who did not follow «orders from the above» and were assaulted or removed from their positions.[75] In an open letter written in 2005, former judge Olga Kudeshkina criticized the chairman of the Moscow city court O. Egorova for «recommending judges to make right decisions» which allegedly caused more than 80 judges in Moscow to retire in the period from 2002 to 2005.[76]

In the 1990s, Russia’s prison system was widely reported by media and human rights groups as troubled. There were large case backlogs and trial delays, resulting in lengthy pre-trial detention. Prison conditions were viewed as well below international standards.[77] Tuberculosis was a serious, pervasive problem.[7] Human rights groups estimated that about 11,000 inmates and prison detainees die annually, most because of overcrowding, disease, and lack of medical care.[78] A media report dated 2006 points to a campaign of prison reform that has resulted in apparent improvements in conditions.[79] The Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation has been working to reform Russia’s prisons since 1997, in concert with reform efforts by the national government.[80]

The rule of law has made very limited inroads in the criminal justice since the Soviet time, especially in the deep provinces.[81]

The courts generally follow the non-acquittals policy; in 2004 acquittals constituted only 0.7 percent of all judgments. Judges are dependent on administrators, bidding prosecutorial offices in turn. The work of public prosecutors varies from poor to dismal. Lawyers are mostly court appointed and low paid. There was a rapid deterioration of the situation characterized by abuse of the criminal process, harassment and persecution of defense bar members in politically sensitive cases in recent years. The principles of adversariness and equality of the parties to criminal proceedings are not observed.[82]

In 1996, President Boris Yeltsin pronounced a moratorium on the death penalty in Russia. However, the Russian government still violates many promises it made upon entering the Council of Europe.[73] According to Politkovskaya, citizens who appeal to European Court of Human Rights are often prosecuted by Russian authorities.[83]

The court system has been widely used to suppress political opposition [84][85][86] as in the cases of Pussy Riot,[87][88] Alexei Navalny,[88][89] Zarema Bagavutdinova,[90] and Vyacheslav Maltsev[91] and to block candidatures of Kremlin’s political enemies.[92][93]

A 2019 report by Zona Prava NGO titled «Violence by Security Forces: Crime Without Punishment» highlighted disproportionately large number of acquittals and dropped cases against law enforcement officers when compared to overall rate of acquittals in Russian courts. The latter is only 0.43%, while in case of law enforcement and military officials accused of violent abuse of power, including ending in death of the suspect, it’s almost 4%. At the same time those convicted also receive disproportionately lenient convictions — almost half of them were suspended sentences or fines.[94]

In 2021 a massive cache of videos from Russian prisons and penal colonies were published by NGO Gulagu.net with thousands of hours of first-hand recordings of torture of inmates by prison officials, involving rape and other forms of sexual assault like penetration with sticks. The videos cover years 2015-2020 and were exfiltrated by a former inmate Sergei Savelyev who was put in charge of the video recording system prison authorities as an IT specialist. Russian authorities fired a few prison officials incriminated in these videos and also placed Savelyev on wanted list for «illegally accessing sensitive information». The abuse was described as part of systematic and countrywide technique for extortion of money and false witness statements by the FSB and law enforcement.[95][96][97]

Torture and abuse[edit]

The Constitution of Russia forbids arbitrary detention, torture and ill-treatment. Chapter 2, Article 21 of the constitution states, «No one may be subjected to torture, violence or any other harsh or humiliating treatment or punishment.»[98][99] However, in practice, Russian police, Federal Security Service[100][101] and prison and jail guards are regularly observed practicing torture with impunity — including beatings with many different types of batons, sticks and truncheons, water battles, sacks with sand etc., the «Elephant Method» which is beating a victim wearing a gas mask with cut airflow and the «Supermarket Method» which is the same but with a plastic bag on head, electric shocks including to genitals, nose, and ears (known as «Phone call to Putin»), binding in stress positions, cigarette burns,[102] needles and electric needles hammered under nails,[103] prolonged suspension, sleep deprivation, food deprivation, rape, penetration with foreign objects, asphyxiation — in interrogating arrested suspects.[103][1][7][8][104]

Another torture method is the «Television» which involves forcing the victim to stand in a mid-squat with extended arms in front of them holding a stool or even two stools, with the seat facing them. Former serviceman Andrei Sychev had to have both legs and genitals amputated after this torture due to gangrene caused by cut bloodflow. Other torture methods include the «Rack» or «Stretch» which involves hanging a victim on hands tied behind the back, the «Refrigerator» which involves subjecting a naked victim sometimes doused in cold water to subzero temperatures, the «Furnace» where the victim is left in heat in a small space and «Chinese torture» where the feet of the victim laying on a tabletop are beaten with clubs.

In 2000, human rights Ombudsman Oleg Mironov estimated that 50% of prisoners with whom he spoke claimed to have been tortured. Amnesty International reported that Russian military forces in Chechnya engage in torture.[98]

Torture at police stations, jails, prisons and penal colonies is common and widespread. Doctors and nurses sometimes also take part in torturing and beating prisoners and suspects.[5][6][7][8][9][10][105]

Russian police is known to be using torture as a means to extract forced confessions of guilt.[106][102][107][108][109][110]

Sometimes police or jail guards employ trusted inmates to beat, torture, and rape suspects in order to force confessions of guilt. This torture method is called «Pressing Room» or «Press Hut». Those trustees receive special prison privileges for torturing other prisoners.[111]

In the most extreme cases, hundreds of innocent people from the street were arbitrarily arrested, beaten, tortured, and raped by special police forces. Such incidents took place not only in Chechnya, but also in Russian towns of Blagoveshensk, Bezetsk, Nefteyugansk, and others.[112][113][114] In 2007 Radio Svoboda («Radio Freedom», part of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty) reported that an unofficial movement «Russia the Beaten» was created in Moscow by human rights activists and journalists who «suffered from beatings in numerous Russian cities».[115]

In June 2013, construction worker Martiros Demerchyan claimed that he was tortured by Sochi police. Demerchyan, who spent seven weeks constructing housing for the 2014 Winter Olympics, was accused by his supervisor of stealing wiring. Demerchyan denied the allegations but when the victim returned to work to collect his pay, he was met by several police officers who beat him all night, breaking two of his teeth and sexually assaulted him with a crow bar. He was treated in hospital, but doctors told his family they had found no serious injuries on his body.[116]

Torture and humiliation are also widespread in the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation. The term dedovshchina refers to systematic abuse of new conscripts by more long-serving soldiers.[117] Many young men are killed, raped or commit suicide every year because of it.[118] It is reported that some young male conscripts are forced to work as prostitutes for «outside clients».[119] Union of the Committees of Soldiers’ Mothers of Russia works to protect rights of young soldiers.

The current phenomenon of dedovschina is closely linked to the division of Soviet and now Russian junior soldiers into four ‘classes,’ each reflecting a group called up every six months for a total two-year service period. This system stemmed from the adoption of two-year service in 1967. The reduction in the term of service to one year and the increasing number of contract servicemen in the Armed Forces may change the character of dedovschina somewhat.

Crime[edit]

In the 1990s, the growth of organized crime (see Russian mafia and Russian oligarchs) and the fragmentation and corruption of law enforcement agencies in Russia coincided with a sharp rise in violence against business figures, administrative and state officials, and other public figures.[120] The second President of Russia Vladimir Putin inherited these problems when he took office, and during his election campaign in 2000, the new president won popular support by stressing the need to restore law and order and to bring the rule of law to Russia as the only way of restoring confidence in the country’s economy.[121]

According to data by Demoscope Weekly, the Russian homicide rate showed a rise from the level of 15 murders per 100,000 people in 1991, to 32.5 in 1994. Then it fell to 22.5 in 1998, followed by a rise to a maximum rate of 30.5 in 2002, and then a fall to 20 murders per 100,000 people in 2006.[122] Despite positive tendency to reduce, Russia’s index of murders per capita remains one of the highest in the world with the fifth highest of 62 nations.[123]

With a prison population rate of 611 per 100,000 population, Russia was second only to the United States (2006 data).[124] Furthermore, criminology studies show that for the first five years since 2000 compared with the average for 1992 to 1999, the rate of robberies is up by 38.2% and the rate of drug-related crimes is higher by 71.7%.[125]

Domestic violence[edit]

Russia has a high rate of domestic violence compared to other European countries like the UK.[126] Russia decriminalized first-offense domestic violence in 2017, making the maximum penalty an administrative fine for an injury that did not result in hospitalization.[126] Victims describe difficulties in getting protection from police that have resulted in severe mutilation or death, and cultural conservatism which considers domestic violence a family rather than a government matter, and denies the concept of marital rape.[126] The Russian Orthodox Church helped defeat a 2019 bill that would have introduced restraining orders for the first time in Russia, and adding prison sentences for first-offence domestic abuse. The church called the law «antifamily» and blamed it on «radical feminist ideology».[127]

During the COVID-19 pandemic in Russia, some women were fined for breaking quarantine rules when they fled their abuses, leading to changes in the regulations.[127] In 2020, the government cut funding for anti-domestic violence efforts by 88% from the previous year.[127] Any anti-domestic violence organization that receives international funding is subject to registration with the government and must label all of its materials «foreign agent».[126] The advertising agency Room 485 in 2020 launched a campaign against the popular sentiment «if he beats you, it means he loves you».[127]

Political freedom[edit]

Elections[edit]

Russia held elections on 4 December 2011. European Parliament called for new free and fair elections and an immediate and full investigation of all reports of fraud. According to MEPs Russia did not meet election standards as defined by the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). The preliminary findings of the OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR) report on procedural violations, lack of media impartiality, harassment of independent monitors and lack of separation between party and state.[128]

Persecution of scientists[edit]

There were several cases where the FSB accused scientists of allegedly revealing state secrets to foreign nationals, while the defendants and their colleagues claimed that the information or technology was based on already published and declassified sources. Even though the cases often garnered public reaction, the cases themselves were in most cases held in closed chambers, with no press coverage or public oversight.

The scientists in question are:

- Igor Sutyagin (sentenced to 15 years).[129]

- Evgeny Afanasyev and Svyatoslav Bobyshev, (sentenced to 12 and a half and 12 years).[130]

- Scientist Igor Reshetin and his associates at the Russian rocket and space researcher TsNIIMash-Export.

- Physicist Valentin Danilov (sentenced to 14 years).[52]

- Physical chemist Oleg Korobeinichev (held under a written pledge not to leave city from 2006.[131] In May 2007 the case against him was closed by FSB for «absence of body of crime». In July 2007 prosecutors publicly apologized to Korobeinichev[132] for «the image of spy»).

- Academic Oskar Kaibyshev (given a 6-year suspended sentence and a fine of $132,000).[133][134]

Ecologist and journalist Alexander Nikitin, who worked with the Bellona Foundation, was likewise accused of espionage. He published material exposing hazards posed by the Russian Navy’s nuclear fleet. He was acquitted in 1999 after spending several years in prison (his case was sent for re-investigation 13 times while he remained in prison). Other cases of prosecution are the cases of investigative journalist and ecologist Grigory Pasko, sentenced to three years’ imprisonment and later released under a general amnesty,[135][136] Vladimir Petrenko who described dangers posed by military chemical warfare stockpiles and was held in pretrial confinement for seven months, and Nikolay Shchur, chairman of the Snezhinskiy Ecological Fund who was held in pretrial confinement for six months.[137]

Viktor Orekhov, a former KGB captain who assisted Soviet dissidents and was sentenced to eight years of prison in the Soviet era, was sentenced in 1995 to three years of prison for alleged possession of a pistol and magazines. After one year he was released and left the country.[138]

Vil Mirzayanov was prosecuted for a 1992 article in which he has claimed that Russia was working on chemical weapons of mass destruction, but won the case and later emigrated to the United States[139]

Vladimir Kazantsev who disclosed illegal purchases of eavesdropping devices from foreign firms was arrested in August 1995, and released at the end of the year, however the case was not closed.[137][140] Investigator Mikhail Trepashkin was sentenced in May 2004 to four years of prison.[51]

On 9 January 2006, journalist Vladimir Rakhmankov was sentenced for alleged defamation of the President in his article «Putin as phallic symbol of Russia» to fine of 20,000 roubles (about 695 USD).[141][142]

Political dissidents from the former Soviet republics, such as authoritarian Tajikistan and Uzbekistan, are often arrested by the FSB and extradited to these countries for prosecution, despite the protests from international human rights organizations.[143][144] The special security services of Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan and Azerbaijan also kidnap people in Russian territory, with the implicit approval of the FSB.[145]

Many people were also held in detention to prevent them from demonstrating during the G8 Summit in 2006.[146]

[edit]

There has been a number of high-profile cases of human rights abuses connected to business in Russia. Among other abuses, this most obviously involves abuse of article 17 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.[147] These include the case of the former heads of the oil company Yukos, Mikhail Khodorkovsky, and Platon Lebedev whom Amnesty International declared prisoners of conscience,[148] and the case of the lawyer Sergei Magnitsky, whose efforts to expose a conspiracy of criminals and corrupt law-enforcement officials earned him sustained abuse in prison which led to his death.[149][150][151] An analogous case was the death in custody of the businesswoman Vera Trifonova, who was in jail for alleged fraud.[152] Cases such as these have contributed to suspicion in other countries about the Russian justice system, which has manifested itself in the refusal to grant Russian extradition requests for businessmen fleeing abroad.[153] Notable instances of this are the cases of the tycoon Boris Berezovsky and former Yukos vice president Alexander Temerko in the UK, the media magnate Vladimir Gusinsky in Spain[154] and Greece,[155] Leonid Nevzlin in Israel[156] and Ivan Kolesnikov in Cyprus.[157] A case that will test the attitude of the French authorities to this issue is that of the shipping magnate Vitaly Arkhangelsky. The WikiLeaks revelations indicated the low level of confidence other governments have in the Russian government on such issues.[158] Cases involving major companies may gain coverage in the world media, but there are many further cases equally worthy of attention: a typical case involves the expropriation of assets, with criminals and corrupt law-enforcement officials collaborating to bring false charges against businesspeople, who are told that they must hand over assets to avoid criminal proceedings against them. A prominent campaigner against such abuses is Yana Yakovleva, herself a victim who set up the group Business Solidarity in the aftermath of her ordeal.[159][160]

Suspicious killings[edit]

Some Russian opposition lawmakers and investigative journalists are suspected to be assassinated while investigating corruption and alleged crimes conducted by state authorities or FSB: Sergei Yushenkov, Yuri Shchekochikhin, Alexander Litvinenko, Galina Starovoitova, Anna Politkovskaya, Paul Klebnikov.[42][43]

USA and UK intelligence services believe Russian government and secret services are behind at least fourteen targeted killings on British soil.[40]

Situation in Chechnya[edit]

The Russian Government’s policies in Chechnya are a cause of international concern.[31][32] It has been reported that Russian military forces have abducted, tortured, and killed numerous civilians in Chechnya,[161] but Chechen separatists have also committed abuses and acts of terrorism,[162] such as abducting people for ransom[163] and bombing Moscow metro stations.[164] Human rights groups are critical of cases of people disappearing in the custody of Russian officials. Systematic illegal arrests and torture conducted by the armed forces under the command of Ramzan Kadyrov and Federal Ministry of Interior have also been reported.[165] There are reports about repressions, information blockade, and atmosphere of fear and despair in Chechnya.[166]

According to Memorial reports,[167][168] there is a system of «conveyor of violence» in Chechen Republic, as well as in neighbouring Ingushetiya. People are suspected in crimes connected with activity of separatists squads, are unlawfully detained by members of security agencies, and then disappear. After a while some detainees are found in preliminary detention centers, while some allegedly disappear forever, and some are tortured to confess to a crime or/and to slander somebody else. Psychological pressure is also in use.[169] Known Russian journalist Anna Politkovskaya compared this system with Gulag and claimed the number of several hundred cases.[170]

A number of journalists were killed in Chechnya purportedly for reporting on the conflict.[13][171] List of names includes less and more famous: Cynthia Elbaum, Vladimir Zhitarenko, Nina Yefimova, Jochen Piest, Farkhad Kerimov,[172] Natalya Alyakina,[173] Shamkhan Kagirov,[174] Viktor Pimenov, Nadezhda Chaikova, Supian Ependiyev, Ramzan Mezhidov and Shamil Gigayev, Vladimir Yatsina,[175] Aleksandr Yefremov,[176] Roddy Scott, Paul Klebnikov, Magomedzagid Varisov,[177] Natalya Estemirova and Anna Politkovskaya.[178]

As reported by the Commissioner for Human Rights of the Council of Europe Thomas Hammarberg in 2009, «prior military conflicts, recurrent terrorist attacks (including suicide bombings), as well as widespread corruption and a climate of impunity have all plagued the region.»[179]

According to the Human Rights Centre Memorial, the total number of alleged abductions in Chechnya was 42 during the entire year 2008, whereas already in the first four months of 2009 there were 58 such cases. Of these 58 persons, 45 had been released, 2 found dead, 4 were missing and 7 had been found in police detention units.[179] In the course of 2008, 164 criminal complaints concerning acts by the security forces were made, 111 of which were granted. In the first half of 2009, 52 such complaints were made, 18 of which were granted.[179]

On 16 April 2009 the counter-terrorism operation (CTO) regime in Chechnya was lifted by the federal authorities. After that, the Chechen authorities bear primary responsibility for the fight against terrorism in the Republic. However, the lifting of the CTO regime has not been accompanied by a diminishment of activity of illegal armed groups in Chechnya.[179]

There are reports on practices of collective punishment of relatives of alleged terrorists or insurgents: punitive house-burning has continued to be among the tactics against families of alleged insurgents. Chechen authorities confirmed such incidents and pointed out that «such practices were difficult to prevent as they stemmed from prevalent customs of revenge», however, educational efforts are undertaken to prevent such incidents, with the active involvement of village elders and Muslim clerics, and compensation had been paid to many of the victims of punitive house burnings.[179]

Current situation[edit]

Chechen leader Ramzan Kadyrov rules the Chechen Republic through despotism and repression.[180]

There are gay concentration camps in Chechnya where homosexuals are tortured and executed.[181][182][183] In September 2017 Tatyana Moskalkova, an official representative of government on human rights, met with Chechnen authorities to discuss a list of 31 people recently extrajudicially killed in the republic.[184]

Governmental organizations[edit]

Efforts to institutionalize official human rights bodies have been mixed. In 1996, human rights activist Sergei Kovalev resigned as chairman of the Presidential Human Rights Commission to protest the government’s record, particularly the war in Chechnya. Parliament in 1997 passed a law establishing a «human rights ombudsman,» a position that is provided for in Russia’s constitution and is required of members of the Council of Europe, to which Russia was admitted in February 1996. The State Duma finally selected Duma deputy Oleg Mironov in May 1998. A member of the Communist Party of the Russian Federation, Mironov resigned from both the Party and the Duma after the vote, citing the law’s stipulation that the Ombudsman be nonpartisan. Because of his party affiliation, and because Mironov had no evident expertise in the field of human rights, his appointment was widely criticized at the time by human rights activists.[citation needed]

Non-governmental organizations[edit]

See also: Russian foreign agent law, Russian undesirable organizations law

The lower house of the Russian parliament passed a bill by 370-18 requiring local branches of foreign non-governmental organizations (NGOs) to re-register as Russian organizations subject to Russian jurisdiction, and thus stricter financial and legal restrictions. The bill gives Russian officials oversight of local finances and activities. The bill has been highly criticized by Human Rights Watch, Memorial organization, and the INDEM Foundation for its possible effects on international monitoring of the status of human rights in Russia.[185] In October 2006 the activities of many foreign non-governmental organizations were suspended using this law; officials said that «the suspensions resulted simply from the failure of private groups to meet the law’s requirements, not from a political decision on the part of the state. The groups would be allowed to resume work once their registrations are completed.»[36] Another crackdown followed in 2007.[186]

The year 2015 saw the dissolution of several NGOs following their registration as foreign agents under the 2012 Russian foreign agent law and the shutdown of NGOs under the 2015 Russian undesirable organizations law.

In March 2016, Russia announced the closure of the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights in Moscow.[187]

Freedom of religion[edit]

The Constitution of Russian Federation provides for freedom of religion and the equality of all religions before the law as well as the separation of church and state. Vladimir Putin claimed in his 2005 Ombudsman’s report that «the Russian state has achieved significant progress in the observance of religious freedom and lawful activity of religious associations, overcoming a heritage of totalitarianism, domination of a single ideology and party dictatorship.»[188] However, reports of religious abuse continue to come out of Russia. According to International Christian Concern, during 2021 «crackdowns on religious freedom have intensified in Russia.»[189] During June 2021, Forum 18 highlighted that «twice as many prisoners of conscience are serving sentences or are in detention awaiting appeals for exercising freedom of religion or belief as in November 2020.»[190] Many religious scholars and human right organizations have recently spoken up about the abuses taking place in Russia against minorities.[191][192] The U.S. State Department considers Russia one of the worlds’ «worst violators» of religious freedom.[193]

Alvaro Gil-Robles emphasized the amount of state support provided by both federal and regional authorities varies for the different religious communities.[19] In harmony with that, Catholics are not always heeded as well as other religions by federal and local authorities.[19]

Vladimir Lukin noted back in 2005, that citizens of Russia rarely experience violations of freedom of conscience (guaranteed by the article 28 of the Constitution)then.[188] The Commissioner’s Office annually accepted between 200 and 250 complaints dealing with violations of rights, usually from worshipers, who represent various confessions: Orthodox (but not belonging to the Moscow patriarchy), Old-believers, Muslim, Protestant and others.[188] Anna Politkovskaya described cases of prosecution and even murders of Muslims by Russia’s law enforcement bodies at the North Caucasus.[194][195] However, there are plenty of Muslims in higher government, Duma, and business.[196]

Additional concerns arise over restrictions of citizens’ right to association (article 30 of the Constitution).[188] As Vladimir Lukin noted over 15 years ago, that the number of registered religious organizations were constantly growing (22,144 in 2005), however presently an increasing number of religious organization fail to achieve legal recognition or are striped of the legal recognition previously given: e.g. Jehovah’s Witnesses, the International Society for Krishna Consciousness, and others.[188]

The influx of missionaries over the past several years has also led to pressure by groups in Russia, specifically nationalists and the Russian Orthodox Church, to limit the activities of these «nontraditional» religious groups.[citation needed] In response, the Duma passed a new, restrictive, and potentially discriminatory law in October 1997. The law is very complex, with many ambiguous and contradictory provisions. The law’s most controversial provisions separates religious «groups» and «organizations» and introduces a 15-year rule, which allows groups that have existed for 15 years or longer to obtain accredited status. According to Russian priest and dissident Gleb Yakunin, new religion law «heavily favors the Russian Orthodox Church at the expense of all other religions, including Judaism, Catholicism, and Protestantism.», and it is «a step backward in Russia’s process of democratization.»[197] Since 2017, Jehovah’s Witnesses have faced persecution for unclear reasons.[198][199]

The claim to guarantee «the exclusion of any legal, administrative and fiscal discrimination against so-called non-traditional confessions» was adopted by PACE in June 2005.[200]

Freedom of movement[edit]

More than four million employees tied to the military and security services were banned from traveling abroad under rules issued during 2014.[201]

In September 2022, Vladimir Putin signed a decree introducing prison terms of up to 15 years for wartime acts, including voluntary surrender and desertion during mobilization or war.[202][203]

Media freedom[edit]

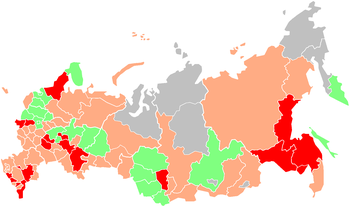

Green: Fairly free

Orange: Not very free

Red: Unfree

Grey: No data. Free regions were not found.

Source: Glasnost Defense Foundation

Reporters Without Borders put Russia at 147th place in the World Press Freedom Index (from a list of 168 countries).[204] According to the Committee to Protect Journalists, 47 journalists have been killed in Russia for their professional activity, since 1992 (as of 15 January 2008). Thirty were killed during President Boris Yeltsin’s reign, and the rest were killed under the president Vladimir Putin.[13][205] According to the Glasnost Defence Foundation, there were 8 cases of suspicious deaths of journalists in 2007, as well as 75 assaults on journalists, and 11 attacks on editorial offices.[206] In 2006, the figures were 9 deaths, 69 assaults, and 12 attacks on offices.[207] In 2005, the list of all cases included 7 deaths, 63 assaults, 12 attacks on editorial offices, 23 incidents of censorship, 42 criminal prosecutions, 11 illegal layoffs, 47 cases of detention by militsiya, 382 lawsuits, 233 cases of obstruction, 23 closings of editorial offices, 10 evictions, 28 confiscations of printed production, 23 cases of stopping broadcasting, 38 refusals to distribute or print production, 25 acts of intimidation, and 344 other violations of Russian journalist’s rights.[208]

Russian journalist Anna Politkovskaya, famous for her criticisms of Russia’s actions in Chechnya, and the pro-Kremlin Chechya government, was assassinated in Moscow. Former KGB officer Oleg Gordievsky believes that the murders of writers Yuri Shchekochikhin (author of Slaves of KGB), Anna Politkovskaya, and Aleksander Litvinenko show that the FSB has returned to the practice of political assassinations,[209] practised in the past by the Thirteenth Department of the KGB.[210]

Opposition journalist Yevgenia Albats in interview with Eduard Steiner has claimed: «Today the directors of the television channels and the newspapers are invited every Thursday into the Kremlin office of the deputy head of administration, Vladislav Surkov to learn what news should be presented, and where. Journalists are bought with enormous salaries.»[211]

According to Amnesty International during and after the 2014 Winter Olympics the Russian authorities adopted an increasingly attacking anti-Western and anti-Ukrainian rhetoric, which was widely echoed in the government-controlled mainstream media. This was followed by the Russo-Ukrainian War and the imposition of international sanctions.[212]

On 28 May 2020, seven journalists and a writer were detained during a peaceful protest. They were holding single person pickets in support of the journalists who had previously been detained. On 29 May 2020, the Moscow police arrested 30 more people, including journalists, activists and district council representatives.[213]

On 6 July 2020, journalist Svetlana Prokopyeva was sentenced by Russian court on fake terrorism charges. She was fined with 500,000 rubles (approximately US$7000). She works for the Echo of Moscow and Radio Free Europe. In her November 2018 radio broadcast on suicide bomber attack on Federal Security Service (FSB) building in Arkhangelsk, she criticized the government on its repressive policies and crackdown on free assembly & free speech that has made peaceful activism impossible. In July 2019, she was listed as «terrorists and extremists» and the authority freezes her assets. In September 2019, she was formally accused of «propaganda of terrorism» that was completely based on her Radio broadcast.[214]

The Russian censorship apparatus Roskomnadzor ordered media organizations to delete stories that describe the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine as an «assault», an «invasion», or a «declaration of war».[215] Roskomnadzor launched an investigation against the Novaya Gazeta, Echo of Moscow, inoSMI, MediaZona, New Times, TV Rain, and other Russian media outlets for publishing «inaccurate information about the shelling of Ukrainian cities and civilian casualties in Ukraine as a result of the actions of the Russian Army».[216] On 1 March 2022, Russian authorities blocked access to Echo of Moscow and TV Rain, Russia’s last independent TV station,[217] claiming that they were spreading «deliberately false information about the actions of Russian military personnel».[218] Additionally, Roskomnadzor threatened to block access to the Russian Wikipedia in Russia over the article «Вторжение России на Украину (2022)» («Russia’s invasion of Ukraine (2022)»), claiming that the article contains «illegally distributed information», including «reports about numerous casualties among service personnel of the Russian Federation and also the civilian population of Ukraine, including children».[219][220]

On 4 March 2022, Roskomnadzor blocked access to several foreign media outlets, including BBC News Russian, Voice of America, RFE/RL, Deutsche Welle and Meduza,[221][222] as well as Facebook and Twitter.[223]

On 4 March 2022, President Vladimir Putin signed into law a bill introducing prison sentences of up to 15 years for those who publish «knowingly false information» about the Russian military and its operations, leading to some media outlets to stop reporting on Ukraine.[224] More than 1,000 Russian journalists have fled Russia since February 2022.[225] Hugh Williamson, Europe and Central Asia director at Human Rights Watch, said that «These new laws are part of Russia’s ruthless effort to suppress all dissent and make sure the [Russian] population does not have access to any information that contradicts the Kremlin’s narrative about the invasion of Ukraine.»[226] In February 2023, Russian journalist Maria Ponomarenko [sv] was sentenced to six years in prison for publishing information about the Mariupol theatre airstrike.[227]

In March 2022, Russian journalist Alexander Nevzorov wrote to the Chairman of Russia’s Investigative Committee Alexander Bastrykin that Russia’s 2022 war censorship laws violate the freedom of speech provisions of the Constitution of Russia.[228] The Russian Constitution expressly prohibits censorship in Article 29 of Chapter 2, Rights and Liberties of Man and Citizen.[229][230] As of December 2022, more than 4,000 people were prosecuted under «fake news» laws.[72]

On 13 July 2022, the United Nations’ human rights experts condemned Russia’s continued and heightened crackdown on civil society groups, human rights defenders and media outlets. Most independent Russian media outlets were closed down to avoid prosecution, or had been blocked along with dozens of foreign media. Of the many thousands of Russians who protested peacefully against the Russian invasion of Ukraine, over 16,000 of them, including many human rights defenders, have been detained.[231]

On 5 September 2022, Russian journalist Ivan Safranov was sentenced to 22 years in prison in relation to the «treason» charges.[232] Russian daily newspaper Kommersant called the charges of treason «absurd».[233] In June 2019, Kommersant was accused in Russian courts with disclosing state secrets; according to BBC News, the case was based on an article co-authored by Safronov[233] about Russian sales of fighter jets to Egypt.[232]

Freedom of assembly[edit]

Russian Constitution (1993) states of the Freedom of assembly that citizens of the Russian Federation shall have the right to gather peacefully, without weapons, and to hold meetings, rallies, demonstrations, marches and pickets.[234]

According to Amnesty International (2013 report) peaceful protests across Russia, including gatherings of small groups of people who presented no public threat or inconvenience, were routinely dispersed by police, often with excessive force. The day before the inauguration of President Putin, peaceful protesters against elections to Bolotnaya Square in Moscow were halted by police. 19 protesters faced criminal charges in connection with events characterized by authorities as «mass riots». Several leading political activists were named as witnesses in the case and had their homes searched in operations that were widely broadcast by state-controlled television channels. Over 6 and 7 May, hundreds of peaceful individuals were arrested across Moscow.[235] According to Amnesty International police used excessive and unlawful force against protestors during the Bolotnaya Square protest on 6 May 2012. Hundreds of peaceful protesters were arrested.[236]

According to a Russian law introduced in 2014, a fine or detention of up to 15 days may be given for holding a demonstration without the permission of authorities and prison sentences of up to five years may be given for three breaches. Single-person pickets have resulted in fines and a three-year prison sentence.[237][238][239][240]

On 9 June 2020, a feminist blogger Yulia Tsvetkova was charged with «pornography dissemination.» She runs a social media group that encourages body positivity and protested against the social taboos related to women. She was put under a 5-month house arrest and banned from traveling. On 27 June 2020, 50 Russian media outlets organized a «Media Strike for Yulia,» appealing the government to drop all charges against Yulia. During the campaign, the activists were peacefully protesting against the government in a single person pickets. The police detained 40 activists for supporting Yulia Tsvetkova. Human Rights Watch urged the authorities to drop all the charges against Yulia for being a feminist and an activist of LGBTQ people.[241]

On 10 July 2020, Human Rights Watch said, several journalists in Russia were detained in a crackdown on peaceful protests and are facing fines. HRW urges Russian authorities to drop the charges against the protesters, journalists and end attacks on freedom of expression.[242]

On 4 August 2020, Human Rights Watch urged the Russian authorities to drop the charges against Yulia Galyamina, a municipal assembly member, who is accused of organizing and participating in unauthorized demonstrations, even though they were peaceful. Her prosecution violated respect for freedom of assembly.[243]

On 12 August 2021, report «RUSSIA: NO PLACE FOR PROTEST» from Amnesty International in which stated that Russian authorities made it almost impossible for protesters to exercise their right to freedom of peaceful assembly. The organization also accused Russia of suppressing peaceful protests using heavy-handed police tactics and by deploying the use of restrictive laws.[244][245]

Ethnic minorities[edit]

Russian Federation is a multi-national state with over 170 ethnic groups designated as nationalities, population of these groups varying enormously, from millions in the case of Russians and Tatars to under ten thousand in the case of Nenets and Samis.[19] Among 83 subjects which constitute the Russian Federation, there are 21 national republics (meant to be home to a specific ethnic minority), 5 autonomous okrugs (usually with substantial or predominant ethnic minority) and an autonomous oblast. However, as Commissioner for Human Rights of the Council of Europe Gil-Robles noted in a 2004 report, whether or not the region is «national», all the citizens have equal rights and no one is privileged or discriminated against on account of their ethnic affiliation.[19]

As Gil-Robles noted, although co-operation and good relations are still generally the rule in most of regions, tensions do arise, whose origins vary. Their sources include problems related to peoples that suffered Stalinist repressions, social and economic problems provoking tensions between different communities, and the situation in Chechnya and the associated terrorist attacks with resulting hostility towards people from the Caucasus and Central Asia, which takes the form of discrimination and overt racism towards the groups in question.[19]

Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe[246] in May 2007 expressed concern that Russia still has not adopted comprehensive anti-discrimination legislation, and the existing anti-discrimination provisions are seldom used in spite of reported cases of discrimination.[247]

As Gil-Robles noted in 2004, minorities are generally represented on local and regional authorities, and participate actively in public affairs. Gil-Robles emphasized the degree of co-operation and understanding between the various nationalities living in the same area, as well as the role of regional and local authorities in ethnic dialogue and development.[19] Along with that, Committee of Ministers in 2007 noted certain setbacks in minority participation in public life, including the abrogation of federal provisions for quotas for indigenous people in regional legislatures.[247]

Although the Constitution of the Russian Federation recognises Russian as the official language, the individual republics may declare one or more official languages. Most subjects have at least two – Russian and the language of the «eponymous» nationality.[19] As Ministers noted in 2007, there is a lively minority language scene in most subjects of the federation, with more than 1,350 newspapers and magazines, 300 TV channels and 250 radio stations in over 50 minority languages. Moreover, new legislation allows usage of minority languages in federal radio and TV broadcasting.[247]

In 2007, there were 6,260 schools which provided teaching in 38 minority languages. Over 75 minority languages were taught as a discipline in 10,404 schools. Ministers of the Council of Europe have noted efforts to improve the supply of minority language textbooks and teachers, as well as greater availability of minority language teaching. However, as Ministers have noted, there remain shortcomings in the access to education of persons belonging to certain minorities.[247]

There are more than 2,000 national minorities’ public associations and 560 national cultural autonomies, however the Committee of Ministers has noted that, in many regions, the amount of state support for the preservation and development of minority cultures is still inadequate.[247] Alvaro Gil-Robles noted in 2004 that there is a significant difference between «eponymous» ethnic groups and nationalities without their own national territory, as resources of the latter are relatively limited.[19]

Russia is also home to a particular category of minority peoples, i.e. small indigenous peoples of the North and Far East, who maintain very traditional lifestyles, often in a hazardous climatic environment, while adapting to the modern world.[19] After the fall of the Soviet Union, the Russian Federation passed legislation to protect the rights of small northern indigenous peoples.[19] Gil-Robles has noted agreements between indigenous representatives and oil companies, which are to compensate for potential damage to people’s habitats due to oil exploration.[19] As the Committee of Ministers of Council of Europe noted in 2007, despite some initiatives for development, the social and economic situation of numerically small indigenous peoples was affected by recent legislative amendments at the federal level, removing some positive measures as regards their access to land and other natural resources.[247]

Alvaro Gil-Robles noted in 2004 that, like many European countries, the Russian Federation is also host to many foreigners who, when concentrated in a particular area, make up so-called new minorities, who experience troubles e.g. with medical treatment due to the absence of registration. Those who are registered encounter other integration problems because of language barriers.[19]

The Committee of Ministers noted in 2007 that, despite efforts to improve access to residency registration and citizenship for national minorities, those measures still have not regularised the situation of all concerned.[247]

Foreigners and migrants[edit]

In October 2002 the Russian Federation has introduced new legislation on legal rights of foreigners, designed to control immigration and clarify foreigners’ rights. Despite this legal achievement, as of 2004, numerous foreign communities in Russia faced difficulties in practice (according to Álvaro Gil-Robles).[19]

As of 2007, almost 8 million migrants were officially registered in Russia,[248] while some 5-7 million migrants do not have legal status.[249]

Most of foreigners arriving in Russia are seeking jobs. In many cases they have no preliminary contracts or other agreements with a local employer. A typical problem is the illegal status of many foreigners (i.e., they are not registered and have no identity papers), what deprives them of any social assistance (as of 2004) and often leads to their exploitation by the employer. Despite that, foreigner workers still benefit, what with seeming reluctance of regional authorities to solve the problem forms a sort of modus vivendi.[19] As Gil-Robles noted, it’s easy to imagine that illegal status of many foreigners creates grounds for corruption. Illegal immigrants, even if they have spent several years in Russia may be arrested at any moment and placed in detention centres for illegal immigrants for further expulsion. As of 2004, living conditions in detention centers are very bad, and expulsion process lacks of funding, what may extend detention of immigrants for months or even years.[19] Along with that, Gil-Robles detected a firm political commitment to find a satisfactory solution among authorities he spoke with.[19]

There’s a special case of former Soviet citizens (currently Russian Federation nationals). With the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russian Federation declared itself a continuation of the Soviet Union and even took the USSR’s seat at the UN Security Council. Accordingly, 1991 Nationality Law recognised all former Soviet citizens permanently resident in the Russian Federation as Russian citizens. However, people born in Russia who weren’t on the Russian territory when the law came into force, as well as some people born in the Soviet Union who lived in Russia but weren’t formally domiciled there weren’t granted Russian citizenship. When at 31 December 2003 former Soviet passports became invalid, those people overnight become foreigners, although many of them considered Russia their home. The majority were deprived their de facto status of Russian Federation nationals, they lost their right to remain in Russian Federation, they were even deprived of retirement benefits and medical assistance. Their morale has also been seriously affected since they feel rejected.[19]

Another special case are Meskhetian Turks. Victims of both Stalin deportation from South Georgia and 1989 pogroms in the Fergana valley in Uzbekistan, some of them were eventually dispersed in Russia. While in most regions of Russia Meskhetian Turks were automatically granted Russian citizenship, in Krasnodar Krai some 15,000 Meskhetian Turks were deprived of any legal status since 1991.[19] Unfortunately, even measures taken by Alvaro Gil-Robles in 2004 didn’t make Krasnodar authorities to change their position; Vladimir Lukin in the 2005 report called it «campaign initiated by local authorities against certain ethnic groups».[188] The way out for a significant number of Meskhetian Turks in the Krasnodar Krai became resettlement in the United States.[250] As Vladimir Lukin noted in 2005, there was similar problem with 5.5 thousand Yazidis who before the disintegration of the USSR moved to the Krasnodar Krai from Armenia. Only one thousand of them were granted citizenship, the others could not be legalized.[188]

In 2006 Russian Federation after initiative proposed by Vladimir Putin adopted legislation which in order to «protect interests of native population of Russia» provided significant restrictions on presence of foreigners on Russian wholesale and retail markets.[251]

There was a short campaign of frequently arbitrary and illegal detention and expulsion of ethnic Georgians on charges of visa violations and a crackdown on Georgian-owned or Georgian-themed businesses and organizations in 2006, as a part of 2006 Georgian-Russian espionage controversy.[252]

Newsweek reported that «[In 2005] some 300,000 people were fined for immigration violations in Moscow alone. [In 2006], according to Civil Assistance, numbers are many times higher.»[253]

A journalist for The Wall Street Journal, Evan Gershkovich, was arrested in March 2023 in Russia on allegations of espionage. The Biden administration identified at least 2 US citizens who are wrongfully detained in Russia.[254]

Racism and xenophobia[edit]

As Álvaro Gil-Robles noted in 2004, the main communities targeted by xenophobia are the Jewish community, groups originating from the Caucasus, migrants and foreigners.[19]

In his 2006 report, Vladimir Lukin had noted rise of nationalistic and xenophobic sentiments in Russia, as well as more frequent cases of violence and mass riots on the grounds of racial, nationalistic or religious intolerance.[34][12][255]

Human rights activists point out that 44 people were murdered and close to 500 assaulted on racial grounds in 2006.[256] According to official sources, there were 150 «extremist groups» with over 5000 members in Russia in 2006.[257]

The Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe has noted in 2007, that high-level representatives of the federal administration have publicly endorsed the fight against racism and intolerance, and a number of programmes have been adopted to implement these objectives. This has been accompanied by an increase in the number of convictions aimed at inciting national, racial or religious hatred. However, there has been an alarming increase in the number of racially motivated violent assaults in the Russian Federation in four years, yet many law enforcement officials still often appear reluctant to acknowledge racial or nationalist motivation in these crimes. Hate speech has become more common in the media and in political discourse. The situation of persons originating in the Northern Caucasus is particularly disturbing.[247]

Vladimir Lukin noted that inactivity of the law enforcement bodies may cause severe consequences, like September 2006 inter-ethnic riot in the town in the Republic of Karelia. Lukin noted provocative role of the so-called Movement Against Illegal Immigration. As the result of the Kondopoga events, all heads of the «enforcement bloc» of the republic were fired from their positions, several criminal cases were opened.[34]

According to nationwide opinion poll carried by VCIOM in 2006, 44% of respondents consider Russia «a common house of many nations» where all must have equal rights, 36% think that «Russians should have more rights since they constitute the majority of the population», 15% think «Russia must be the state of Russian people». However the question is also what exactly does the term «Russian» denote. For 39% of respondents Russians are all who grew and were brought up in Russia’s traditions; for 23% Russians are those who works for the good of Russia; 15% respondents think that only Russians by blood may be called Russians; for 12% Russians are all for who Russian language is native, for 7% Russians are adepts of Russian Christian Orthodox tradition.[258]

According to statistics published by Russian Ministry of Internal Affairs, in 2007 in Russia foreign citizens and people without citizenship has committed 50,1 thousand crimes, while the number of crimes committed against this social group was 15985.[259]

As reported by the Associated Press, in 2010 SOVA Center noted a significant drop of racially motivated violence in Russia in 2009, related to 2008: «71 people were killed and 333 wounded in racist attacks last [2009] year, down from 110 killed and 487 wounded in 2008». According to a SOVA Center report, the drop was mostly «due to police efforts to break up the largest and most aggressive extremist groups in Moscow and the surrounding region». Most of the victims were «dark-skinned, non-Slavic migrant laborers from former Soviet republics in Central Asia … and the Caucasus». As Associated Press journalist Peter Leonard commended, «The findings appear to vindicate government claims it is trying to combat racist violence».[260] In 2018, there were

Under serious police pressure, the number of racist acts started to decline in Russia from 2009.[261]

In 2016, it was reported that racism in Russia has seen «impressive» decrease in hate crimes.[262]

Sexual orientation and gender identity[edit]

Neither same-sex marriages nor civil unions of same-sex couples are allowed in Russia. Article 12 of the Family Code de facto states that marriage is a union of a man and a woman.[263]

In June 2013, parliament unanimously adopted the Russian gay propaganda law, banning promotion among children of «propaganda of nontraditional sexual relationships,» meaning lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender (LGBT) relationships.[264] Violators risk stiff fines, and in the case of foreigners, up to 15 days’ detention and deportation. Beginning in 2006, similar laws outlawing «propaganda of homosexuality» among children were passed in 11 Russian regions. Critics contend the law makes illegal holding any sort of public demonstration in favour of gay rights, speak in defence of LGBT rights, and distribute material related to LGBT culture, or to state that same-sex relationships are equal to heterosexual relationships.[265]

Also in June, parliament passed a law banning adoption of Russian children by foreign same-sex couples and by unmarried individuals from countries where marriage for same-sex couples is legal.[266] In September, several deputies introduced a bill that would make a parent’s homosexuality legal grounds for denial of parental rights. It was withdrawn later for revision.

Homophobic rhetoric, including by officials, and rising homophobic violence accompanied debate about these laws. Three homophobic murders were reported in various regions of Russia in May 2013.[267]

Vigilante groups, consisting of radical nationalists, and neo-Nazis, lure men or boys to meetings, accuse them of being gay, humiliate and beat them, and post videos of the proceedings on social media. For example, in September 2013 a video showed the rape of an Uzbek migrant in Russia who was threatened with a gun and forced to say he was gay. A few investigations were launched, but have not yet resulted in effective prosecution.[268]

In a report issued on 13 April 2017, a panel of five expert advisors to the United Nations Human Rights Council—Vitit Muntarbhorn, Sètondji Roland Adjovi, Agnès Callamard, Nils Melzer and David Kaye—condemned the wave of torture and killings of gay men in Chechnya.[269][270]

Psychiatric institutions[edit]

There are numerous cases in which people who are problematic for Russian authorities have been imprisoned in psychiatric institutions during the past several years.[271][272][273]

Little has changed in the Moscow Serbsky Institute where many prominent Soviet dissidents had been incarcerated after having been diagnosed with sluggishly progressing schizophrenia. This Institute conducts more than 2,500 court-ordered evaluations per year. When war criminal Yuri Budanov was tested there in 2002, the panel conducting the inquiry was led by Tamara Pechernikova, who had condemned the poet Natalya Gorbanevskaya in the past. Budanov was found not guilty by reason of «temporary insanity». After public outrage, he was found sane by another panel that included Georgi Morozov, the former Serbsky director who had declared many dissidents insane in the 1970s and 1980s.[274] Serbsky Institute also made an expertise of mass poisoning of hundreds of Chechen school children by an unknown chemical substance of strong and prolonged action, which rendered them completely incapable for many months.[275] The panel found that the disease was caused simply by «psycho-emotional tension».[276][277]

Disabled people and children’s rights[edit]

|

|

This section needs to be updated. Please help update this article to reflect recent events or newly available information. (August 2021) |

Currently, an estimated 2 million children live in Russian orphanages, with another 4 million children on the streets.[278] According to a 1998 Human Rights Watch report,[279] «Russian children are abandoned to the state at a rate of 113,000 a year for the past two years, up dramatically from 67,286 in 1992. Of a total of more than 600,000 children classified as being ‘without parental care,’ as many as one-third reside in institutions, while the rest are placed with a variety of guardians. From the moment the state assumes their care, orphans in Russia – of whom 95 percent still have a living parent – are exposed to shocking levels of cruelty and neglect.» Once officially labelled as retarded, Russian orphans are «warehoused for life in psychoneurological institutions. In addition to receiving little to no education in such institutions, these orphans may be restrained in cloth sacks, tethered by a limb to furniture, denied stimulation, and sometimes left to lie half-naked in their own filth. Bedridden children aged five to seventeen are confined to understaffed lying-down rooms as in the baby houses, and in some cases are neglected to the point of death.» Life and death of disabled children in the state institutions was described by writer Rubén Gallego.[280][281]

Despite these high numbers and poor quality of care, recent[when?] laws have made adoption of Russian children by foreigners considerably more difficult.

Human trafficking[edit]

The end of communism and collapse of the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia has contributed to an increase in human trafficking, with the majority of victims being women forced into prostitution.[282][283] Russia is a country of origin for persons, primarily women and children, trafficked for the purpose of sexual exploitation. Russia is also a destination and transit country for persons trafficked for sexual and labour exploitation from regional and neighbouring countries into Russia and beyond. Russia accounted for one-quarter of the 1,235 identified victims reported in 2003 trafficked to Germany. The Russian government has shown some commitment to combat trafficking but has been criticised for failing to develop effective measures in law enforcement and victim protection.[284][285]

See also[edit]

- International Human Rights Film Festival «Stalker», a Russian film festival

- Judiciary of Russia

- Moscow Helsinki Group

- Politics of Russia

- Presidential Council for Civil Society and Human Rights

- Russian war crimes

- LGBT rights in Russia

Notes[edit]

- ^ The Constitution of the Russian Federation should not to be confused with its national legislation.

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Rough Justice: The law and human rights in the Russian Federation (PDF). Amnesty International. 2003. ISBN 0-86210-338-X. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 December 2003. Retrieved 16 March 2008.

- ^ Amnesty International Report 2020/21. Amnesty International. 2021. pp. 302–307. ISBN 9780862105013. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ^ «Russia: Events of 2019». World Report 2020: Russia. 2020. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ^ a b «Dozens of Russian Prisoners Tortured, Found Dead in Jail — Washington Free Beacon». Freebeacon.com. 14 January 2016. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ^ a b «Torture by police in Russia is an everyday occurrence—and it isn’t going to stop». Newsweek.com. 29 March 2016. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ^ a b «Russia: Peaceful Protester Alleges Torture». Hrw.org. 27 February 2017. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ^ a b c d «Torture and ill-treatment». Amnesty International. Archived from the original on 4 November 2002. Retrieved 16 March 2008.

- ^ a b c «Chechnya: Research Shows Widespread and Systematic Use of Torture: UN Committee against Torture Must Get Commitments From Russia to Stop Torture». Human Rights Watch. 12 November 2006. Archived from the original on 11 November 2008. Retrieved 26 September 2015.

- ^ a b «There is torture at penal colony number 7: Prisoners and their relatives talk about the situation in the Segezha prison». Meduza.io. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ^ a b «Russian prisons are essentially torture chambers». Dw.com. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ^ «Ethnic minorities under attack». Amnesty International. Archived from the original on 4 November 2002. Retrieved 16 March 2008.

- ^ a b ‘Dokumenty!’: Discrimination on grounds of race in the Russian Federation (PDF). Amnesty International. 2003. ISBN 0-86210-322-3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 April 2003. Retrieved 16 March 2008.

- ^ a b c «Journalists killed: Statistics and Background». Committee to Protect Journalists. Archived from the original on 7 July 2009. Retrieved 9 July 2009. (As of 9 July 2009).

- ^ «Partial Justice: An Enquiry into Deaths of Journalists in Russia 1993 — 2009». Ifj.org. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ^ Ratified, respectively, in 1973 and 1975 by the USSR. Although a Soviet lawyer helped to draft the UN’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights (198), the Communist bloc abstained as a whole from that voluntary affirmation, see A Chronicle of Current Events, «International Agreements».

- ^ The Constitution of the Russian Federation. Washington, D.C.: Embassy of the Russian Federation. Archived from the original on 30 January 2004. Retrieved 16 March 2008.

- ^ «The Constitution of the Russian Federation». www.russianembassy.org. Archived from the original on 10 February 2004. Retrieved 24 June 2019.

Article 15. 4. The commonly recognized principles and norms of the international law and the international treaties of the Russian Federation shall be a component part of its legal system. If an international treaty of the Russian Federation stipulates other rules than those stipulated by the law, the rules of the international treaty shall apply.