Почему в Китае внезапно сменился командующий стратегическими ядерными силами

Его предшественник и зам ранее надолго «исчезли» из публичного поля, как и смещенный глава МИДа

Новым командующим Ракетных войск (аналог российских РВСН) Народно-освободительной армии Китая (НОАК) назначен генерал-полковник Ван Хоубинь, до того занимавший пост заместителя командующего Военно-морских сил (ВМС) НОАК. Его заместителем стал генерал-полковник, член Центрального комитета Коммунистической партии Китая (КПК) Сюй Сишэн.

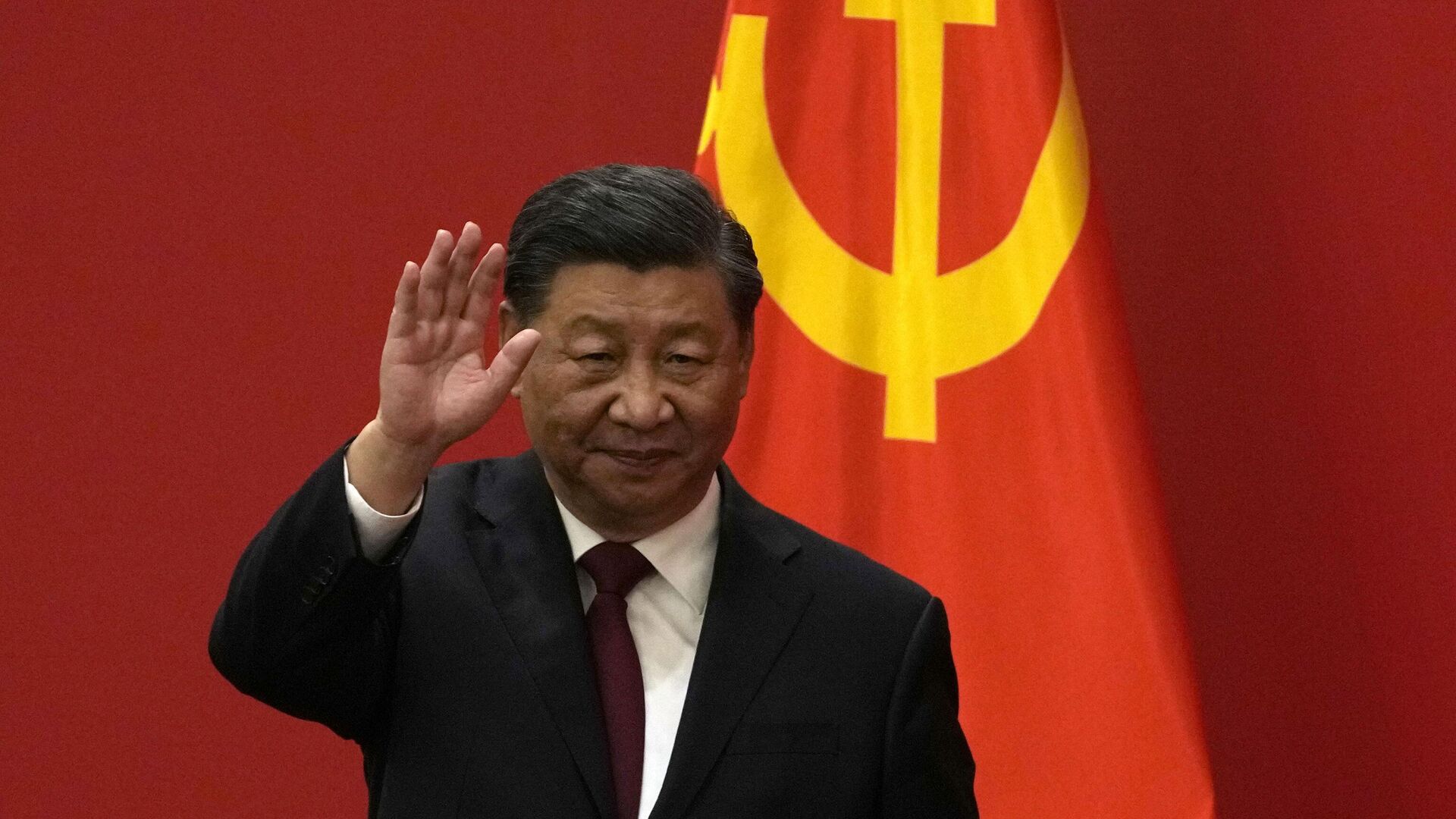

Соответствующее решение 1 августа принял председатель КНР Си Цзиньпин, о чем было объявлено по Центральному телевидению Китая. Ван заменил генерала Ли Юйчао, а Сюй – Лю Гуанбиня, которые последние несколько месяцев не появлялись на публике. Это самая крупная незапланированная перестановка в военном руководстве Китая за последнее десятилетие.

За день до назначения Вану и Сюю присвоены звания генерал-полковников – высшие в НОАК, следует из сообщения минобороны КНР. Соответствующие грамоты им вручил председатель КНР Си Цзиньпин.

Позже китайские Caixin и Beijing Youth Daily отметили, что церемония присвоения званий генерал-полковников Вану и Сюю – уже третья, проведенная Центральным военным советом в 2023 г. (его возглавляет председатель КНР). Ван и Сюй ранее занимали должности замкомандующего ВМС НОАК и заместителя политкомиссара командования Южного ТВД соответственно и не имели отношения к стратегическим ядерным силам.

Это самая необычная перестановка с 2014 г., которая, скорее всего, призвана подчеркнуть полный контроль китайской компартии над вооруженными силами страны.

Гонконгская South China Morning Post (SCMP) ранее сообщала, что снятые с постов руководители могли столкнуться с обвинениями в коррупции при работе с оборонными предприятиями в Пекине. Кроме них под преследование мог попасть и заместитель начальника Объединенного штаба Центрального военного совета КНР Чжан Чжэньчжун. Расследование, по данным газеты, могло начаться после смены министра обороны КНР в марте 2023 г. – тогда Вэй Фэнхэ сменил Ли Шанфу.

Эксперты пекинского аналитического центра военной науки «Юань Ван» в комментарии SCMP отметили, что переход Ван Хоубиня из ВМС в Ракетные войска можно назвать беспрецедентным, но с другой стороны – свидетельствующим об уверенности НОАК в своих возможностях по ведению боевых действий разного вида. Упор на интеграцию ядерных систем воздушного, наземного и морского базирования может быть направлен на усиление координации всех боевых подразделений. Кроме того, перестановки могут быть ставкой на приток «свежей крови» в руководство армии.

Ли Юйчао /CCTV

Смещенный с поста 60-летний Ли Юйчао окончил Университет национальной обороны НОАК и поступил на службу во Второй артиллерийский корпус, который в 2016 г. и был преобразован в Ракетные войска. С апреля 2020 г. по январь 2022 г. Ли был начальником штаба Ракетных войск, а затем получил там главный пост. В ноябре он 2022 г. был избран в состав ЦК КПК.

Покинувший пост 60-летний Лю Гуанбинь с 2016 по 2019 г. был ректором Инженерного университета ракетных войск НОАК, в 2018 г. получил еще и пост начальника управления по оснащению Ракетных войск, а последнее повышение получил в июне 2022 г.

Ван Хоубинь /mod.gov.ch

Назначенный командующим Ракетных войск 62-летний Ван Хоубинь находится на военно-морской службе НОАК с 1979 г. В январе 2016 г. он получил должность начальника штаба Южного флота ВМС, а в 2018 г. был повышен до замначальника штаба ВМС. С декабря 2019 г. до нового назначения в 2023 г. Ван был замкомандующего всего флота Китая.

25 июля после еще одного «исчезновения» из публичного поля длиной ровно в месяц со своего поста был снят министр иностранных дел КНР Цинь Ган. Его преемником стал уже ранее занимавший почти 10 лет министерское кресло Ван И, который при этом сохранил пост заведующего канцелярией Комиссии ЦК КПК по иностранным делам (куратор всей внешней политики). Среди самых обсуждаемых версий об истинной причине отставки экс-министра в западных СМИ – его возможная внебрачная связь с телеведущей гонконгской Phoenix TV Фу Сяотянь, которой он давал интервью в марте 2022 г.

Китайский флот за последнее время заметно расширился: например, он имеет в своем составе как ядерный компонент в виде атомных ракетных подводных лодок, так и значительное количество береговых комплексов тяжелых противокорабельных ракет, говорит директор ЦКЕМИ НИУ ВШЭ Василий Кашин. Ван Хоубинь как раз имеет бэкграунд в сфере береговых ракетных войск и потому может понимать необходимую техническую специфику на новой позиции. Кроме того, само по себе командование в НОАК любыми войсками подразумевает не оперативное командование и управление войсками, а ответственность за развитие – закупки, научно-техническая политика и т. п., говорит эксперт.

Прошлые же руководители Ракетных войск, вероятней всего, исчезли из публичного поля именно из-за расследования в связи с злоупотреблением полномочиями, предполагает Кашин. Логично, что новый руководитель в такой ситуации – человек извне, да еще и в тандеме с политкомиссаром Сюй Сишэном, который отвечает во многом за надзор и дисциплину, заключил Кашин.

| People’s Liberation Army | |

|---|---|

| 中国人民解放军 Zhōngguó Rénmín Jiěfàngjūn |

|

Emblem of the People’s Liberation Army |

|

Flag of the People’s Liberation Army |

|

| Motto | 为人民服务 («Serve the People») |

| Founded | 1 August 1927; 96 years ago |

| Current form | 10 October 1947; 75 years ago[1][2][3] |

| Service branches |

|

| Headquarters | August First Building (ceremonial), etc., Fuxing Road, Haidian District, Beijing |

| Website | eng |

| Leadership | |

| Governing body | |

| CMC leadership | Chairman: Vice Chairmen:

|

| Minister of National Defense | |

| Director of the Political Work Department | |

| Chief of the Joint Staff Department | |

| Secretary of Discipline Inspection Commission | |

| Personnel | |

| Military age | 18 |

| Conscription | Yes by law, but not enforced in practice. All adult males must register for the draft.[4] |

| Active personnel | 2,035,000 (2022)[5] (ranked 1st) |

| Reserve personnel | 510,000 (2022)[5] |

| Expenditures | |

| Budget | US$293 billion (2022)[6] (ranked 2nd) |

| Percent of GDP | 1.7% (2022)[6] |

| Industry | |

| Domestic suppliers |

|

| Foreign suppliers |

Historical:

|

| Annual imports | US$14.858 billion (2010–2021)[8] |

| Annual exports | US$18.121 billion (2010–2021)[8] |

| Related articles | |

| History | History of the PLA Modernization of the PLA Historical Chinese wars and battles Military engagements |

| Ranks | Army ranks Navy ranks Air force ranks |

| Chinese People’s Liberation Army | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 中国人民解放军 | ||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 中國人民解放軍 | ||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | «China People Liberation Army» | ||||||||||||||||

|

The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) is the principal military force of the People’s Republic of China and the armed wing of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). The PLA consists of five service branches: the Ground Force, Navy, Air Force, Rocket Force, and Strategic Support Force. It is under the leadership of the Central Military Commission (CMC) with its chairman as commander-in-chief.

The PLA can trace its origins during the Republican Era to the left-wing units of the National Revolutionary Army (NRA) of the Kuomintang (KMT) when they broke away in 1927 in an uprising against the nationalist government as the Chinese Red Army, before being reintegrated into the NRA as units of New Fourth Army and Eighth Route Army during the Second Sino-Japanese War. The two NRA communist units were reconstituted as the PLA in 1947.[9] Since 1949, the PLA has used nine different military strategies, which it calls «strategic guidelines». The most important came in 1956, 1980, and 1993.[10] In times of national emergency, the People’s Armed Police (PAP) and the China Militia act as a reserve and support element for the PLAGF. Politically, the PLA and PAP are represented in the National People’s Congress (NPC) through a delegation of 285 deputies, all of whom are CCP members. Since the formation of the NPC, the joint PLA–PAP delegation has always constituted the largest delegation and today comprises just over 9% of the NPC.[11]

PRC law explicitly asserts the leadership of the CCP over the armed forces of China and designates the CMC as the nationwide military command of the People’s Republic of China. The Party CMC operates under the name of the State CMC for legal and governmental functions and as the ceremonial Ministry of National Defense (MoD) for diplomatic functions. The PLA is obliged to follow the principle of the CCP’s absolute civilian control of the military under the doctrine of «the party commands the gun» (Chinese: 党指挥枪; pinyin: Dǎng zhǐhuī qiāng)[10] In this sense, the PLA is not a national army of the type of traditional nation-states, but a political army or the armed branch of the CCP itself since its allegiance is to the party only and not the state or any constitution. At present, the CMC chairman is customarily also the CCP general secretary.[12]

Today, the majority of military units around the country are assigned to one of five theater commands by geographical location. The PLA is the world’s largest military force (not including paramilitary or reserve forces) and has the second largest defense budget in the world. China’s military expenditure was US$292 billion in 2022, accounting for 13 percent of the world’s defense expenditures.[13] It is also one of the fastest modernizing militaries in the world, and has been termed as a potential military superpower, with significant regional defense and rising global power projection capabilities.[14][15]

Stated mission[edit]

In 2004, paramount leader Hu Jintao stated the mission of the PLA as:[16]

- The insurance of CCP leadership

- The protection of the sovereignty, territorial integrity, internal security and national development of the People’s Republic of China

- Safeguarding the country’s interests

- Maintaining and safeguarding world peace

History[edit]

Early history[edit]

The CCP founded its military wing on 1 August 1927 during the Nanchang uprising, beginning the Chinese Civil War. Communist elements of the National Revolutionary Army rebelled under the leadership of Zhu De, He Long, Ye Jianying, Zhou Enlai, and other leftist elements of the Kuomintang (KMT), after the Shanghai massacre of 1927.[17] They were then known as the Chinese Workers’ and Peasants’ Red Army, or simply the Red Army.[18]

In 1934 and 1935, the Red Army survived several campaigns led against it by Chiang Kai-Shek’s KMT and engaged in the Long March.[19]

During the Second Sino-Japanese War from 1937 to 1945, the CCP’s military forces were nominally integrated into the National Revolutionary Army of the Republic of China forming two main units, the Eighth Route Army and the New Fourth Army.[9] During this time, these two military groups primarily employed guerrilla tactics, generally avoiding large-scale battles with the Japanese, at the same time consolidating by recruiting KMT troops and paramilitary forces behind Japanese lines into their forces.[20]

After the Japanese surrender in 1945, the CCP continued to use the National Revolutionary Army unit structures until the decision was made in February 1947 to merge the Eighth Route Army and New Fourth Army, renaming the new million-strong force the People’s Liberation Army (PLA).[9] The reorganization was completed by late 1948. The PLA eventually won the Chinese Civil War, establishing the People’s Republic of China in 1949.[21] It then underwent a drastic reorganization, with the establishment of the Air Force leadership structure in November 1949, followed by the Navy leadership structure the following April.[22][23]

In 1950, the leadership structures of the artillery, armored troops, air defense troops, public security forces, and worker–soldier militias were also established. The chemical warfare defense forces, the railroad forces, the communications forces, and the strategic forces, as well as other separate forces (like engineering and construction, logistics and medical services), were established later on.

In this early period, the People’s Liberation Army overwhelmingly consisted of peasants.[24] Its treatment of soldiers and officers was egalitarian[24] and formal ranks were not adopted until 1955.[25] As a result of its egalitarian organization, the early PLA overturned strict traditional hierarchies that governed the lives of peasants.[24] As sociologist Alessandro Russo summarizes, the peasant composition of the PLA hierarchy was a radical break with Chinese societal norms and «overturned the strict traditional hierarchies in unprecedented forms of egalitarianism[.]»[24]

Modernization and conflicts[edit]

During the 1950s, the PLA with Soviet assistance began to transform itself from a peasant army into a modern one.[26] Since 1949, China has used nine different military strategies, which the PLA calls «strategic guidelines». The most important came in 1956, 1980, and 1993.[10] Part of this process was the reorganization that created thirteen military regions in 1955. The PLA also contained many former National Revolutionary Army units and generals who had defected to the PLA.[citation needed]

In November 1950, some units of the PLA under the name of the People’s Volunteer Army intervened in the Korean War as United Nations forces under General Douglas MacArthur approached the Yalu River.[27] Under the weight of this offensive, Chinese forces drove MacArthur’s forces out of North Korea and captured Seoul, but were subsequently pushed back south of Pyongyang north of the 38th Parallel.[27] The war also catalyzed the rapid modernization of the PLAAF.[28]

In 1962, the PLA ground force also fought India in the Sino-Indian War, achieving limited objectives.[29][30] In a series of border clashes in 1967 with Indian troops, the PLA suffered heavy numerical and tactical losses.[31][32][33]

Before the Cultural Revolution, military region commanders tended to remain in their posts for long periods. As the PLA took a stronger role in politics, this began to be seen as somewhat of a threat to the CCP’s (or, at least, civilian) control of the military.[citation needed] The longest-serving military region commanders were Xu Shiyou in the Nanjing Military Region (1954–74), Yang Dezhi in the Jinan Military Region (1958–74), Chen Xilian in the Shenyang Military Region (1959–73), and Han Xianchu in the Fuzhou Military Region (1960–74).[34]

In the early days of the Cultural Revolution, the PLA abandoned the use of the military ranks that it had adopted in 1955.[35]

The establishment of a professional military force equipped with modern weapons and doctrine was the last of the Four Modernizations announced by Zhou Enlai and supported by Deng Xiaoping.[36][37] In keeping with Deng’s mandate to reform, the PLA has demobilized millions of men and women since 1978 and has introduced modern methods in such areas as recruitment and manpower, strategy, and education and training.[38] In 1979, the PLA fought Vietnam over a border skirmish in the Sino-Vietnamese War where both sides claimed victory.[39] However, western analysts agree that Vietnam handily outperformed the PLA.[34]

During the Sino-Soviet split, strained relations between China and the Soviet Union resulted in bloody border clashes and mutual backing of each other’s adversaries.[40] China and Afghanistan had neutral relations with each other during the King’s rule.[41] When the pro-Soviet Afghan Communists seized power in Afghanistan in 1978, relations between China and the Afghan communists quickly turned hostile.[42][better source needed] The Afghan pro-Soviet communists supported China’s enemies in Vietnam and blamed China for supporting Afghan anticommunist militants.[43] China responded to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan by supporting the Afghan mujahideen and ramping up their military presence near Afghanistan in Xinjiang.[43] China acquired military equipment from the United States to defend itself from Soviet attacks.[44]

The People’s Liberation Army Ground Force trained and supported the Afghan Mujahideen during the Soviet-Afghan War, moving its training camps for the mujahideen from Pakistan into China itself.[45] Hundreds of millions of dollars worth of anti-aircraft missiles, rocket launchers, and machine guns were given to the Mujahideen by the Chinese.[46] Chinese military advisors and army troops were also present with the Mujahideen during training.[47]

Since 1980[edit]

In 1981, the PLA conducted its largest military exercise in North China since the founding of the People’s Republic.[10][48] In the 1980s, China shrunk its military considerably to free up resources for economic development, resulting in the relative decline in resources devoted to the PLA.[49] Following the PLA’s suppression of the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and massacre, ideological correctness was temporarily revived as the dominant theme in Chinese military affairs.[50]

Reform and modernization have today resumed their position as the PLA’s primary objectives, although the armed forces’ political loyalty to the CCP has remained a leading concern.[51][52] Another area of concern to the political leadership was the PLA’s involvement in civilian economic activities. These activities were thought to have impacted PLA readiness and have led the political leadership to attempt to divest the PLA from its non-military business interests.[53][54]

Beginning in the 1980s, the PLA tried to transform itself from a land-based power centered on a vast ground force to a smaller, more mobile, high-tech one capable of mounting operations beyond its borders.[10] The motivation for this was that a massive land invasion by Russia was no longer seen as a major threat, and the new threats to China are seen to be a declaration of independence by Taiwan, possibly with assistance from the United States, or a confrontation over the Spratly Islands.[55]

In 1985, under the leadership of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party and the CMC, the PLA changed from being constantly prepared to «hit early, strike hard and to fight a nuclear war» to developing the military in an era of peace.[10] The PLA reoriented itself to modernization, improving its fighting ability, and becoming a world-class force. Deng Xiaoping stressed that the PLA needed to focus more on quality rather than on quantity.[55]

The decision of the Chinese government in 1985 to reduce the size of the military by one million was completed by 1987. Staffing in military leadership was cut by about 50 percent. During the Ninth Five Year Plan (1996–2000) the PLA was reduced by a further 500,000. The PLA had also been expected to be reduced by another 200,000 by 2005. The PLA has focused on increasing mechanization and informatization to be able to fight a high-intensity war.[55]

Former CMC chairman Jiang Zemin in 1990 called on the military to «meet political standards, be militarily competent, have a good working style, adhere strictly to discipline, and provide vigorous logistic support» (Chinese: 政治合格、军事过硬、作风优良、纪律严明、保障有力; pinyin: zhèngzhì hégé, jūnshì guòyìng, zuòfēng yōuliáng, jìlǜ yánmíng, bǎozhàng yǒulì).[56] The 1991 Gulf War provided the Chinese leadership with a stark realization that the PLA was an oversized, almost-obsolete force.[57][58]

The possibility of a militarized Japan has also been a continuous concern to the Chinese leadership since the late 1990s.[59] In addition, China’s military leadership has been reacting to and learning from the successes and failures of the American military during the Kosovo War,[60] the 2001 invasion of Afghanistan,[61] the 2003 invasion of Iraq,[62] and the Iraqi insurgency.[62] All these lessons inspired China to transform the PLA from a military based on quantity to one based on quality. Chairman Jiang Zemin officially made a «Revolution in Military Affairs» (RMA) part of the official national military strategy in 1993 to modernize the Chinese armed forces.[63]

A goal of the RMA is to transform the PLA into a force capable of winning what it calls «local wars under high-tech conditions» rather than a massive, numbers-dominated ground-type war.[63] Chinese military planners call for short decisive campaigns, limited in both their geographic scope and their political goals. In contrast to the past, more attention is given to reconnaissance, mobility, and deep reach. This new vision has shifted resources towards the navy and air force. The PLA is also actively preparing for space warfare and cyber-warfare.[64][65][66]

In 2002, the PLA began holding military exercises with militaries from other countries.[67]: 242 From 2018 to 2023, more than half of these exercises have focused on military training other than war, generally antipiracy or antiterrorism exercises involving combatting non-state actors.[67]: 242 In 2009, the PLA held its first military exercise in Africa, a humanitarian and medical training practice conducted in Gabon.[67]: 242

For the past 10 to 20 years, the PLA has acquired some advanced weapons systems from Russia, including Sovremenny class destroyers,[68] Sukhoi Su-27[69] and Sukhoi Su-30 aircraft,[70] and Kilo-class diesel-electric submarines.[71] It has also started to produce several new classes of destroyers and frigates including the Type 052D class guided-missile destroyer.[72][73] In addition, the PLAAF has designed its very own Chengdu J-10 fighter aircraft[74] and a new stealth fighter, the Chengdu J-20.[75] The PLA launched the new Jin class nuclear submarines on 3 December 2004 capable of launching nuclear warheads that could strike targets across the Pacific Ocean[76] and have three aircraft carriers, with the latest, the Fujian, launched in 2022.[77][78][79]

From 2014 to 2015, the PLA deployed 524 medical staff on a rotational basis to combat the Ebola virus outbreak in Liberia, Sierra Leone, Guinea, and Guinea-Bissau.[67]: 245 As of 2023, this was the PLA’s largest medical assistance mission in another country.[67]: 245

In 2015, the PLA formed new units including the PLA Ground Force, the PLA Rocket Force and the PLA Strategic Support Force.[80]

The PLA on 1 August 2017 marked its 90th anniversary.[81] Before the big anniversary it mounted its biggest parade yet and the first outside of Beijing, held in the Zhurihe Training Base in the Northern Theater Command (within the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region).[82]

Overseas deployments and peacekeeping operations[edit]

The People’s Republic of China has sent the PLA to various hotspots as part of China’s role as a prominent member of the United Nations.[83] Such units usually include engineers and logistical units and members of the paramilitary People’s Armed Police and have been deployed as part of peacekeeping operations in Lebanon,[84][85] the Republic of the Congo,[84] Sudan,[86] Ivory Coast,[87] Haiti,[88][89] and more recently, Mali and South Sudan.[84][90]

Engagements[edit]

- 1927–1950: Chinese Civil War[91]

- 1937–1945: Second Sino-Japanese War[92]

- 1949: Yangtze incident against British warships on the Yangtze River[93]

- 1949: Incorporation of Xinjiang into the People’s Republic of China[94]

- 1950: Annexation of Tibet by the People’s Republic of China[95]

- 1950–1953: Korean War under the banner of the Chinese People’s Volunteer Army[96]

- 1954–1955: First Taiwan Strait Crisis[97]

- 1955–1970: Vietnam War[98]

- 1958: Second Taiwan Strait Crisis at Quemoy and Matsu[99]

- 1962: Sino-Indian War[100]

- 1967: Border skirmishes with India[101]

- 1969: Sino-Soviet border conflict[102]

- 1974: Battle of the Paracel Islands with South Vietnam[103]

- 1979: Sino-Vietnamese War[104]

- 1979–1990: Sino-Vietnamese conflicts 1979–1990[105]

- 1988: Johnson South Reef Skirmish with Vietnam[106]

- 1989: Enforcement of martial law in Beijing during the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and massacre[107]

- 1990: Baren Township riot[108]

- 1995–1996: Third Taiwan Strait Crisis[109]

- 1997: PLA establishes Hong Kong Garrison

- 1999: PLA establishes Macau Garrison

- 2007–present: UNIFIL peacekeeping operations in Lebanon[84]

- 2009–present: Anti-piracy operations in the Gulf of Aden[110]

- 2014: Search and rescue efforts for Flight MH370[111]

- 2014: UN peacekeeping operations in Mali[112]

- 2015: UNMISS peacekeeping operations in South Sudan[113]

- 2020–present: China–India skirmishes[114]

Organization[edit]

National military command[edit]

The state military system upholds the principle of the CCP’s absolute leadership over the armed forces. The party and the State jointly established the CMC that carries out the task of supreme military leadership over the armed forces. The 1954 Constitution stated that the State President directs the armed forces and made the State President the chairman of the National Defense Commission. The National Defense Commission is an advisory body and does not hold any actual power over the armed forces.

On 28 September 1954, the Central Committee of the CCP re-established the CMC as the commanding organ of the PLA.[citation needed] From that time onward, the current system of a joint system of party and state leadership of the military was established. The Central Committee of the CCP leads in all military affairs. The State President directs the state military forces and the development of the military forces which is managed by the State Council.

To ensure the absolute leadership of the CCP over the armed forces, every level of the party committee in the military forces implements the principles of democratic centralism.[citation needed] In addition, division-level and higher units establish political commissars and political organizations, ensuring that the branch organizations are in line. These systems combined the party organization with the military organization to achieve the party’s leadership and administrative leadership. This is seen as the key guarantee to the absolute leadership of the CCP over the military.

In October 2014 the People’s Liberation Army Daily reminded readers of the Gutian Congress, which stipulated the basic principle of CCP control of the military, and called for vigilance as «[f]oreign hostile forces preach the nationalization and de-politicization of the military, attempting to muddle our minds and drag our military out from under the Party’s flag.»[115]

Leadership[edit]

The leadership by the CCP is a fundamental principle of the Chinese military command system. The PLA reports not to the State Council but rather to two Central Military Commissions, one belonging to the state and one belonging to the CCP.

In practice, the two central military commissions usually do not contradict each other because their membership is usually identical. Often, the only difference in membership between the two occurs for a few months every five years, during the period between a party congress, when Party CMC membership changes, and the next ensuing National People’s Congress, when the state CMC changes. The CMC carries out its responsibilities as authorised by the Constitution and National Defense Law.[116]

The leadership of each type of military force is under the leadership and management of the corresponding part of the Central Military Commission of the CCP Central Committee. Forces under each military branch or force such as the subordinate forces, academies and schools, scientific research and engineering institutions and logistical support organisations are also under the leadership of the CMC. This arrangement has been especially useful as China over the past several decades has moved increasingly towards military organisations composed of forces from more than one military branch.

In September 1982, to meet the needs of modernisation and to improve coordination in the command of forces including multiple service branches and to strengthen unified command of the military, the CMC ordered the abolition of the leadership organisation of the various military branches. Today, the PLA has an air force, navy and second artillery leadership organs.

In 1986, the People’s Armed Forces Department, except in some border regions, was placed under the joint leadership of the PLA and the local authorities.[citation needed] Although the local party organizations paid close attention to the People’s Armed Forces Department, as a result of some practical problems, the CMC decided that from 1 April 1996, the People’s Armed Forces Department would once again fall under the jurisdiction of the PLA.[citation needed]

According to the Constitution of the People’s Republic of China, the CMC is composed of the following: the chairman, Vice-chairmen and Members. The Chairman of the Central Military Commission has overall responsibility for the commission.

The Central Military Commission of the Chinese Communist Party and the Central Military Commission of the People’s Republic of China

- Chairman

- Xi Jinping (also General Secretary, President and Commander-in-chief of Joint Battle Command)

- Vice Chairmen

- General Zhang Youxia

- General He Weidong

- Members

- Minister of National Defense – General Li Shangfu

- Chief of the Joint staff – General Liu Zhenli

- Director of the Political Work Department – Admiral Miao Hua

- Secretary of the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection – General Zhang Shengmin

Central Military Commission[edit]

In December 1982, the fifth National People’s Congress revised the state constitution to state that the State Central Military Commission (CMC) leads all the armed forces of the state. The chairman of the State CMC is chosen and removed by the full NPC while the other members are chosen by the NPC standing committee. However, the CMC of the Central Committee of the CCP remained the party organization that directly commands the military and all the other armed forces.

In actual practice, the party CMC, after consultation with political representatives, proposes the names of the State CMC members of the NPC so that these people after going through the legal processes can be elected by the NPC to the State Central Military Commission (CMC). That is to say, the CMC of the Central Committee and the CMC of the State are one group and one organisation. However, looking at it organizationally, these two CMCs are subordinate to two different systems – the party system and the state system.

Therefore, the armed forces are under the absolute leadership of the CCP and are also the armed forces of the state. This is a unique joint leadership system that reflects the origin of the PLA as the military branch of the CCP. It only became the national military when the People’s Republic of China was established in 1949.

By convention, the chairman and vice-chairman of the Central Military Commission (CMC) are civilian members of the CCP, but they are not necessarily the heads of the civilian government. Both Jiang Zemin and Deng Xiaoping retained the office of chairman even after relinquishing their other positions. All of the other members of the CMC are uniformed active military officials. Unlike other nations, the Minister of National Defense is not the head of the military but is usually a vice-chairman of the CMC.

2016 military reforms[edit]

On 1 January 2016, the CMC released guidelines[117] on deepening national defense and military reform, about a month after Xi Jinping called for an overhaul of the military administration and command system.[citation needed]

On 11 January 2016, the PLA was restructured and a joint staff department directly attached to the CMC.[citation needed] The previous four general headquarters of the PLA were disbanded. They were divided into 15 functional departments instead – an expansion from the domain of the General Office, which is now a single department within the Central Military Commission.[citation needed]

- General Office (办公厅)

- Joint Staff Department (联合参谋部)

- Political Work Department (政治工作部)

- Logistic Support Department (后勤保障部)

- Equipment Development Department (装备发展部)

- Training and Administration Department (训练管理部)

- National Defense Mobilization Department (国防动员部)

- Discipline Inspection Commission (纪律检查委员会)

- Politics and Legal Affairs Commission (政法委员会)

- Science and Technology Commission (科学技术委员会)

- Office for Strategic Planning (战略规划办公室)

- Office for Reform and Organizational Structure (改革和编制办公室)

- Office for International Military Cooperation (国际军事合作办公室)

- Audit Office (审计署)

- Agency for Offices Administration (机关事务管理总局)

Included among the 15 departments are three commissions. The CMC Discipline Inspection Commission is charged with rooting out corruption.

| Central Military Commission | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Departments | Commissions | Offices | Forces Directly under the CMC | Research institutes | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| General Office | Discipline Inspection Commission | Office for Strategic Planning | Joint Logistic Support Force[118] | Academy of Military Science | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Joint Staff Department | Politics and Legal Affairs Commission | Office for Reform and Organizational Structure | National Defence University | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Political Work Department | Science and Technology Commission | Office for International Military Cooperation | National University of Defense Technology | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Logistic Support Department | Audit Office | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Equipment Development Department | Agency for Offices Administration | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Training and Administration Department | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| National Defense Mobilization Department | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Theater commands | Service Branches | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Eastern Theater Command | PLA Ground Force | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Western Theater Command | PLA Navy | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Southern Theater Command | PLA Air Force | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Northern Theater Command | PLA Rocket Force | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Central Theater Command | PLA Strategic Support Force | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| People’s Liberation Army | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Theater commands[edit]

Until 2016, China’s territory was divided into seven military regions, but they were reorganized into five theater commands in early 2016. This reflects a change in their concept of operations from primarily ground-oriented to mobile and coordinated movement of all services.[120] The five new theatre commands, in order of stated significance are:

- Eastern Theater Command

- Southern Theater Command

- Western Theater Command

- Northern Theater Command

- Central Theater Command[121]

The PLA garrisons in Hong Kong and Macau both come under the Southern Theater Command.[citation needed]

The military reforms have also introduced a major change in the areas of responsibility. Rather than separately commanding their troops, service branches are now primarily responsible for administrative tasks (like equipping and maintaining the troops). It is the theater commands now that have the command authority. This should, in theory, facilitate the implementation of joint operations across all service branches.[122]

Coordination with civilian national security groups such as the Ministry of Foreign Affairs is achieved primarily by the leading groups of the CCP. Particularly important are the leading groups on foreign affairs, which include those dealing with Taiwan.[citation needed]

Ranks[edit]

Officers[edit]

| Rank group | General / flag officers | Senior officers | Junior officers | Officer cadet | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| 上将 Shàngjiàng |

中将 Zhōngjiàng |

少将 Shàojiàng |

大校 Dàxiào |

上校 Shàngxiào |

中校 Zhōngxiào |

少校 Shàoxiào |

上尉 Shàngwèi |

中尉 Zhōngwèi |

少尉 Shàowèi |

学员 Xuéyuán |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| 海军上将 Hǎijūn shàngjiàng |

海军中将 Hǎijūn zhōngjiàng |

海军少将 Hǎijūn shàojiàng |

海军大校 Hǎijūn dàxiào |

海军上校 Hǎijūn shàngxiào |

海军中校 Hǎijūn zhōngxiào |

海军少校 Hǎijūn shàoxiào |

海军上尉 Hǎijūn shàngwèi |

海军中尉 Hǎijūn zhōngwèi |

海军少尉 Hǎijūn shàowèi |

海军学员 Hǎijūn xuéyuán |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| 空军上将 Kōngjūn shàngjiàng |

空军中将 Kōngjūn zhōngjiàng |

空军少将 Kōngjūn shàojiàng |

空军大校 Kōngjūn dàxiào |

空军上校 Kōngjūn shàngxiào |

空军中校 Kōngjūn zhōngxiào |

空军少校 Kōngjūn shàoxiào |

空军上尉 Kōngjūn shàngwèi |

空军中尉 Kōngjūn zhōngwèi |

空军少尉 Kōngjūn shàowèi |

空军学员 Kōngjūn xuéyuán |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| 上将 Shàngjiàng |

中将 Zhōngjiàng |

少将 Shàojiàng |

大校 Dàxiào |

上校 Shàngxiào |

中校 Zhōngxiào |

少校 Shàoxiào |

上尉 Shàngwèi |

中尉 Zhōngwèi |

少尉 Shàowèi |

学员 Xuéyuán |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| 上将 Shàngjiàng |

中将 Zhōngjiàng |

少将 Shàojiàng |

大校 Dàxiào |

上校 Shàngxiào |

中校 Zhōngxiào |

少校 Shàoxiào |

上尉 Shàngwèi |

中尉 Zhōngwèi |

少尉 Shàowèi |

学员 Xuéyuán |

Other ranks[edit]

| Rank group | Senior NCOs | Junior NCOs | Enlisted | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 一级军士长 Yījí jūnshìzhǎng |

二级军士长 Èrjí jūnshìzhǎng |

三级军士长 Sānjí jūnshìzhǎng |

四级军士长 Sìjí jūnshìzhǎng |

上士 Shàngshì |

中士 Zhōngshì |

下士 Xiàshì |

上等兵 Shàngděngbīng |

列兵 Lièbīng |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 海军一级军士长 Hǎijūn yījí jūnshìzhǎng |

海军二级军士长 Hǎijūn èrjí jūnshìzhǎng |

海军三级军士长 Hǎijūn sānjí jūnshìzhǎng |

海军四级军士长 Hǎijūn sìjí jūnshìzhǎng |

海军上士 Hǎijūn shàngshì |

海军中士 Hǎijūn zhōngshì |

海军下士 Hǎijūn xiàshì |

海军上等兵 Hǎijūn shàngděngbīng |

海军列兵 Hǎijūn lièbīng |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 空军一级军士长 Kōngjūn yījí jūnshìzhǎng |

空军二级军士长 Kōngjūn èrjí jūnshìzhǎng |

空军三级军士长 Kōngjūn sānjí jūnshìzhǎng |

空军四级军士长 Kōngjūn sìjí jūnshìzhǎng |

空军上士 Kōngjūn shàngshì |

空军中士 Kōngjūn zhōngshì |

空军下士 Kōngjūn xiàshì |

空军上等兵 Kōngjūn shàngděngbīng |

空军列兵 Kōngjūn lièbīng |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

No equivalent |

|

|

| Master sergeant class one 一级军士长 yījí jūnshìzhǎng |

Master sergeant class two 二级军士长 èrjí jūnshìzhǎng |

Master sergeant class three 三级军士长 sānjí jūnshìzhǎng |

Master sergeant class four 四级军士长 sìjí jūnshìzhǎng |

Sergeant first class 上士 shàngshì |

Sergeant 中士 zhōngshì |

Corporal 下士 xiàshì |

Private first class 上等兵 shàngděngbīng |

Private 列兵 lièbīng |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 一级军士长 Yījí jūnshìzhǎng |

二级军士长 Èrjí jūnshìzhǎng |

三级军士长 Sānjí jūnshìzhǎng |

四级军士长 Sìjí jūnshìzhǎng |

上士 Shàngshì |

中士 Zhōngshì |

下士 Xiàshì |

上等兵 Shàngděngbīng |

列兵 Lièbīng |

Service branches[edit]

The PLA encompasses five main service branches (Chinese: 军种; pinyin: jūnzhǒng): the Ground Force, the Navy, the Air Force, the Rocket Force, and the Strategic Support Force. Following the 200,000 troop reduction announced in 2003, the total strength of the PLA has been reduced from 2.5 million to just under 2.3 million. Further reforms will see an additional 300,000 personnel reduction from its current strength of 2.28 million personnel. The reductions will come mainly from non-combat ground forces, which will allow more funds to be diverted to naval, air, and strategic missile forces. This shows China’s shift from ground force prioritisation to emphasising air and naval power with high-tech equipment for offensive roles over disputed coastal territories.[124]

In recent years, the PLA has paid close attention to the performance of US forces in Afghanistan and Iraq. As well as learning from the success of the US military in network-centric warfare, joint operations, C4ISR, and hi-tech weaponry, the PLA is also studying unconventional tactics that could be used to exploit the vulnerabilities of a more technologically advanced enemy. This has been reflected in the two parallel guidelines for the PLA ground forces development. While speeding up the process of introducing new technology into the force and retiring the older equipment, the PLA has also emphasized asymmetric warfare, including exploring new methods of using existing equipment to defeat a technologically superior enemy.[citation needed]

In addition to the four main service branches, the PLA is supported by two paramilitary organizations: the People’s Armed Police (including the China Coast Guard, CCG) and the Militia (including the maritime militia).[citation needed]

Ground Force (PLAGF)[edit]

The PLA Ground Force (PLAGF) is the largest of the PLA’s five services with 975,000 active duty personnel, approximately half of the PLA’s total manpower of around 2 million personnel.[125] The PLAGF is organized into twelve active duty group armies sequentially numbered from the 71st Group Army to the 83rd Group Army which are distributed to each of the PRC’s five theatre commands, receiving two to three group armies per command. In wartime, numerous PLAGF reserve and paramilitary units may be mobilized to augment these active group armies. The PLAGF reserve component comprises approximately 510,000 personnel divided into thirty infantry and twelve anti-aircraft artillery (AAA) divisions. The PLAGF is led by Commander Liu Zhenli and Political Commissar Qin Shutong.[126][127]

While much of the PLA Ground Force was being reduced over the past few years, technology-intensive elements such as special operations forces (SOF), army aviation, surface-to-air missiles (SAMs), and electronic warfare units have all experienced rapid expansion. The latest operational doctrine of the PLA ground forces highlights the importance of information technology, electronic and information warfare, and long-range precision strikes in future warfare. The older generation telephone/radio-based command, control, and communications (C3) systems are being replaced by an integrated battlefield information networks featuring local/wide-area networks (LAN/WAN), satellite communications, unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV)-based surveillance and reconnaissance systems, and mobile command and control centers.[128][unreliable source?]

Navy (PLAN)[edit]

Until the early 1990s, the PLA Navy (PLAN) performed a subordinate role to the PLA Ground Force (PLAGF). Since then it has undergone rapid modernisation. The 300,000 strong PLAN is organised into three major fleets: the North Sea Fleet headquartered at Qingdao, the East Sea Fleet headquartered at Ningbo, and the South Sea Fleet headquartered in Zhanjiang.[129] Each fleet consists of a number of surface ship, submarine, naval air force, coastal defence, and marine units.[130][131]

The navy includes a 25,000 strong Marine Corps (organised into seven brigades), a 26,000 strong Naval Aviation Force operating several hundred attack helicopters and fixed-wing aircraft.[132] As part of its overall programme of naval modernisation, the PLAN is in the stage of developing a blue water navy.[133] In November 2012, then Party General Secretary Hu Jintao reported to the CCP’s 18th National Congress his desire to «enhance our capacity for exploiting marine resource and build China into a strong maritime power».[134] According to the United States Department of Defense, the PLAN has numerically the largest navy in the world.[135] The PLAN is led by Commander Dong Jun and Political Commissar Yuan Huazhi.[136][137]

Air Force (PLAAF)[edit]

The 395,000 strong People’s Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF) is organised into five Theater Command Air Forces (TCAF) and 24 air divisions.[138] The largest operational units within the Aviation Corps is the air division, which has 2 to 3 aviation regiments, each with 20 to 36 aircraft. The surface-to-air missile (SAM) Corps is organised into SAM divisions and brigades. There are also three airborne divisions manned by the PLAAF. J-XX and XXJ are names applied by Western intelligence agencies to describe programs by the People’s Republic of China to develop one or more fifth-generation fighter aircraft.[139][140] The PLAAF is led by Commander Chang Dingqiu and Political Commissar Guo Puxiao.[141][142]

Rocket Force (PLARF)[edit]

The People’s Liberation Army Rocket Force (PLARF) is the main strategic missile force of the PLA and consists of at least 120,000 personnel.[143] It controls China’s nuclear and conventional strategic missiles.[144] China’s total nuclear arsenal size is estimated to be between 100 and 400 thermonuclear warheads. The PLARF is organised into bases sequentially numbered from 61 through 67, wherein the first six are operational and allocated to the nation’s theater commands while Base 67 serves as the PRC’s central nuclear weapons storage facility.[145] The PLARF is led by Command Li Yuchao and Political Commissar Xu Zhongbo.[146][147]

Strategic Support Force (PLASSF)[edit]

Founded on 31 December 2015 as part of the first wave of reforms of the PLA, the People’s Liberation Army Strategic Support Force (PLASSF) was established as the newest and latest branch of the PLA. Personnel numbers are estimated at 175,000.[143] Initial announcements regarding the Strategic Support Force did not provide much detail, but Yang Yujun of the Chinese Ministry of Defense described it as an integration of all current combat support forces including but limited to space, cyber, electronic and intelligence branches. Additionally, commentators have speculated that the new service branch will include high-tech operations forces such as space, cyberspace and electronic warfare operations units, independent of other branches of the military.[148]

Yin Zhuo, rear admiral of the People’s Liberation Army Navy and member of the eleventh Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC) said that «the major mission of the PLA Strategic Support Force is the provision of support to the combat operations so that the PLA can gain regional advantages in the aerospace, space, network and electromagnetic space warfare and ensure integrated operations in the conduction of US joint warfare style operations.»[149]

Conscription and terms of service[edit]

Technically, military service with the PLA is obligatory for all Chinese citizens. In practice, mandatory military service has not been implemented since 1949 as the People’s Liberation Army has been able to recruit sufficient numbers voluntarily.[150] All 18-year-old males have to register themselves with the government authorities, in a way similar to the Selective Service System of the United States. In practice, registering does not mean that the person doing so must join the People’s Liberation Army.[citation needed]

Article 55 of the Constitution of the People’s Republic of China prescribes conscription by stating: «It is a sacred duty of every citizen of the People’s Republic of China to defend his or her motherland and resist invasion. It is an honoured obligation of the citizens of the People’s Republic of China to perform military service and to join the militia forces.»[151] The 1984 Military Service Law spells out the legal basis of conscription, describing military service as a duty for «all citizens without distinction of race … and religious creed». This law has not been amended since it came into effect. Technically, those 18–22 years of age enter selective compulsory military service, with a 24-month service obligation. In reality, numbers of registering personals are enough to support all military posts in China, creating «volunteer conscription».[152][better source needed]

Residents of the Special administrative regions, Hong Kong and Macau, are exempted from joining the military.

Departments[edit]

Joint Staff Department[edit]

The Joint Staff Department carries out staff and operational functions for the PLA and had major responsibility for implementing military modernisation plans. Headed by the chief of the joint staff (formerly chief of the general staff), the department serves as the headquarters for the entire PLA and contained directorates for the five armed services: Ground Forces, Air Force, Navy, Rocket Forces and Support Forces.

The Joint Staff Department included functionally organised subdepartments for operations, training, intelligence, mobilisation, surveying, communications and politics. The departments for artillery, armoured units, quartermaster units and joint forces engineering units were later dissolved, with the former two forming now part of the Ground Forces. The engineering formations are now split amongst the service branches and the quartermaster formations today form part of the Joint Logistics Forces.

Navy Headquarters controls the North Sea Fleet, East Sea Fleet, and South Sea Fleet. Air Force Headquarters generally exercised control through the commanders of the five theater commands. Nuclear forces were directly subordinate to the Joint Staff Department through the Rocket Forces commander and political commissar. Conventional main, regional, and militia units were controlled administratively by the theater commanders, but the Joint Staff Department in Beijing could assume direct operational control of any main-force unit at will.

Thus, broadly speaking, the Joint Staff Department exercises operational control of the main forces, and the theater commanders controlled as always the regional forces and, indirectly, the militia. The post of principal intelligence official in the top leadership of the Chinese military has been taken up by several people of several generations, from Li Kenong in the 1950s to Xiong Guangkai in the late 1990s; and their public capacity has always been assistant to the deputy chief of staff or assistant to the chief of staff.

Ever since the CCP officially established the system of «theater commands» for its army in the 2010s as a successor to the «major military regions» policy of the 1950s, the intelligence agencies inside the Army have, after going through several major evolutions, developed into the present three major military intelligence setups:

- The central level is composed of the Second and Third Departments under the Joint Staff Headquarters and the Liaison Department under the Political Work Department.

- At the Theater Command level intelligence activities consist of the Second Bureau established at the same level as the Operation Department under the headquarters, and the Liaison Department established under the Political Work Department.

- The third system includes several communications stations directly established in the garrison areas of all the theater commands by the Third Department of the Joint Staff Headquarters.

The Second Bureau under the headquarters and the Liaison Department under the Political Work Departments of the theater commands are only subjected to the «professional leadership» of their «counterpart» units under the Central Military Commission (CMC) and are still considered the direct subordinate units of the major military region organizationally. Those entities whose names include the word «institute», all research institutes under the charge of the Second and the Third Departments of the Joint Staff Headquarters, including other research organs inside the Army, are at least of the establishment size of brigade level. Among the deputy commanders of a major Theater command in China, there is always one who is assigned to take charge of intelligence work, and the intelligence agencies under his charge are directly affiliated to the headquarters and the political department of the corresponding theater command.

The Conference on Strengthening Intelligence Work was held 3–18 September 1996 at the Xishan Command Center of the Ministry of State Security and the General Staff Department. Chi Haotian delivered a report entitled «Strengthen Intelligence Work in a New International Environment To Serve the Cause of Socialist Construction.» The report emphasised the need to strengthen the following four aspects of intelligence work:

- Efforts must be made to strengthen understanding of the special nature and role of intelligence work, as well as an understanding of the close relationship between strengthening intelligence work on the one hand, and of the Four Modernizations of the motherland, the reunification of the motherland, and opposition to hegemony and power politics on the other.

- The United States and the West have all along been engaged in infiltration, intervention, sabotage, and intelligence gathering against China on the political, economic, military, and ideological fronts. The response must strengthen the struggle against their infiltration, intervention, sabotage, and intelligence gathering.

- Consolidating intelligence departments and training a new generation of intelligence personnel who are politically reliable, honest and upright in their ways, and capable of mastering professional skills, the art of struggle, and advanced technologies.

- Strengthening the work of organising intelligence in two international industrial, commercial, and financial ports – Hong Kong and Macau.

Although the four aspects emphasised by Chi Haotian appeared to be defensive measures, they were both defensive and offensive in nature.

Second Department[edit]

The Second Department of the Joint Staff Headquarters is responsible for collecting military intelligence. Activities include military attachés at Chinese embassies abroad, clandestine special agents sent to foreign countries to collect military information, and the analysis of information publicly published in foreign countries. This section of the PLA Joint Staff Headquarters act in a similar capacity to its civilian counterpart the Ministry of State Security.

The Second Department oversees military human intelligence (HUMINT) collection, widely exploits open source (OSINT) materials, fuses HUMINT, signals intelligence (SIGINT), and imagery intelligence data, and disseminates finished intelligence products to the CMC and other consumers. Preliminary fusion is carried out by the Second Department’s Analysis Bureau which mans the National Watch Center, the focal point for national-level indications and warning. In-depth analysis is carried out by regional bureaus. Although traditionally the Second Department of the Joint Staff Department was responsible for military intelligence, it is beginning to increasingly focus on scientific and technological intelligence in the military field, following the example of Russian agencies in stepping up the work of collecting scientific and technological information.

The research institute under the Second Department of the Joint Staff Headquarters is publicly known as the Institute for International Strategic Studies; its internal classified publication «Foreign Military Trends» (Chinese: 外军动态, Wai Jun Dongtai) is published every 10 days and transmitted to units at the division level.

The PLA Institute of International Relations at Nanjing comes under the Second Department of the Joint Staff Department and is responsible for training military attachés, assistant military attachés and associate military attachés as well as secret agents to be posted abroad. It also supplies officers to the military intelligence sections of various military regions and group armies. The institute was formed from the PLA «793» Foreign Language Institute, which moved from Zhangjiakou after the Cultural Revolution and split into two institutions at Luoyang and Nanjing.

The Institute of International Relations was known in the 1950s as the School for Foreign Language Cadres of the Central Military Commission (CMC), with the current name being used since 1964. The training of intelligence personnel is one of several activities at the institute. While all graduates of the Moscow Institute of International Relations were employed by the KGB, only some graduates of the Beijing Institute of International Relations are employed by the Ministry of State Security.

The former Institute of International Relations, since being renamed the Foreign Affairs College, is under the administration of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and is not involved in secret intelligence work. The former Central Military Commission (CMC) foreign language school had foreign faculty members who were either CCP sympathizers or were members of foreign communist parties. But the present Institute of International Relations does not hire foreign teachers, to avoid the danger that its students might be recognised when sent abroad as clandestine agents.

Those engaged in professional work in military academies under the Second Department of the Joint Staff Headquarters usually have a chance to go abroad, either for advanced studies or as military officers working in the military attaché’s office of Chinese embassies in foreign countries. People working in the military attaché’s office of embassies are usually engaged in collecting military information under the cover of «military diplomacy». As long as they refrain from directly subversive activities, they are considered as well-behaved «military diplomats».

Some bureaus under the Second Department are responsible for espionage in different regions, of which the First Bureau is responsible for collecting information in the Special Administrative Regions of Hong Kong and Macau, and also in Taiwan. Agents are dispatched by the Second Department to companies and other local corporations to gain cover.

The «Autumn Orchid» intelligence group assigned to Hong Kong and Macau in the mid-1980s mostly operated in the mass media, political, industrial, commercial, and religious circles, as well as in universities and colleges. The «Autumn Orchid» intelligence group was mainly responsible for the following three tasks:

- Finding out and keeping abreast of the political leanings of officials of the Hong Kong and Macau governments, as well as their views on major issues, through social contact with them and information provided by them.

- Keeping abreast of the developments of foreign governments’ political organs in Hong Kong, as well as of foreign financial, industrial, and commercial organisations.

- Finding out and having a good grasp of the local media’s sources of information on political, military, economic, and other developments on the mainland, and deliberately releasing false political or military information to the media to test the outside response.

The «Autumn Orchid» intelligence group was awarded a Citation for Merit, Second Class, in December 1994. It was further awarded another Citation for Merit, Second Class, in 1997. Its current status is not publicly known. During the 2008 Chinese New Year celebration CCTV held for Chinese diplomatic establishments, the head of the Second Department of the Joint Headquarters was revealed for the first time to the public: the current head was Major General Yang Hui (Chinese: 杨晖).

Third Department[edit]

The Third Department of the Joint Staff Department is responsible for monitoring the telecommunications of foreign armies and producing finished intelligence based on the military information collected.

The communications stations established by the Third Department of the Joint Staff Headquarters are not subject to the jurisdiction of the provincial military district and the major theater command of where they are based. The communications stations are entirely the agencies of the Third Department of the Joint Staff Headquarters which have no affiliations to the provincial military district and the military region of where they are based. The personnel composition, budgets, and establishment of these communications stations are entirely under the jurisdiction of the Third Department of the General PLA General Staff Headquarters and are not related at all with local troops.

China maintains the most extensive SIGINT network of all the countries in the Asia-Pacific region. As of the late 1990s, SIGINT systems included several dozen ground stations, half a dozen ships, truck-mounted systems, and airborne systems. Third Department headquarters is in the vicinity of the GSD First Department (Operations Department), AMS, and NDU complex in the hills northwest of the Summer Palace. As of the late 1990s, the Third Department was allegedly manned by approximately 20,000 personnel, with most of their linguists trained at the Luoyang Institute of Foreign Languages.

Ever since the 1950s, the Second and Third Departments of the Joint Staff Headquarters have established several institutions of secondary and higher learning for bringing up «special talents». The PLA Foreign Language Institute at Luoyang comes under the Third Department of the Joint Staff Department and is responsible for training foreign language officers for the monitoring of foreign military intelligence. The institute was formed from the PLA «793» Foreign Language Institute, which moved from Zhangjiakou after the Cultural Revolution and split into two institutions at Luoyang and Nanjing.

Though the distribution order they received upon graduation indicated the «Joint Staff Headquarters», many of the graduates of these schools found themselves being sent to all parts of the country, including remote and uninhabited backward mountain areas. The reason is that the monitoring and control stations under the Third Department of the PLA General Staff Headquarters are scattered in every corner of the country.

The communications stations located in the Shenzhen base of the PLA Hong Kong Garrison started their work long ago. In normal times, these two communications stations report directly to the Central Military Commission (CMC) and the Joint Staff Headquarters. Units responsible for coordination are the communications stations established in the garrison provinces of the military regions by the Third Department of the PLA General Staff Headquarters.

By taking direct command of military communications stations based in all parts of the country, the CCP Central Military Commission (CMC) and the Joint Staff Headquarters can not only ensure a successful interception of enemy radio communications, but can also make sure that none of the wire or wireless communications and contacts among major military regions can escape the detection of these communications stations, thus effectively attaining the goal of imposing direct supervision and control over all the theater commands, all provincial military districts, and all group armies.

Monitoring stations[edit]

China’s main SIGINT effort is in the Third Department of the Joint Staff Department of the Central Military Commission (CMC), with additional capabilities, primarily domestic, in the Ministry of State Security (MSS). SIGINT stations, therefore, are scattered through the country, for domestic as well as international interception. Prof. Desmond Ball, of the Australian National University, described the largest stations as the main Technical Department SIGINT net control station on the northwest outskirts of Beijing, and the large complex near Lake Kinghathu in the extreme northeast corner of China.

As opposed to other major powers, China focuses its SIGINT activities on its region rather than the world. Ball wrote, in the eighties, that China had several dozen SIGINT stations aimed at the Soviet Union, Japan, Taiwan, Southeast Asia and India, as well as internally. Of the stations apparently targeting Russia, there are sites at Jilemutu and Jixi in the northeast, and at Erlian and Hami near the Mongolian border. Two Russian-facing sites in Xinjiang, at Qitai and Korla may be operated jointly with resources from the US CIA’s Office of SIGINT Operations, probably focused on missile and space activity.

Other stations aimed at South and Southeast Asia are on a net controlled by Chengdu, Sichuan. There is a large facility at Dayi, and, according to Ball, «numerous» small posts along the Indian border. Other significant facilities are located near Shenyang, near Jinan and in Nanjing and Shanghai. Additional stations are in the Fujian and Guangdong military districts opposite Taiwan.

On Hainan Island, there is a naval SIGINT facility that monitors the South China sea, and a ground station targeting US and Russian satellites. China also has ship and aircraft platforms in this area, under the South Sea Fleet headquarters at Zhanjiang immediately north of the island. Targeting here seems to have an ELINT as well as COMINT flavor. There are also truck-mounted mobile ground systems, as well as ship, aircraft, and limited satellite capability. There are at least 10 intelligence-gathering auxiliary vessels.

As of the late nineties, the Chinese did not appear to be trying to monitor the United States Pacific Command to the same extent as does Russia. In future, this had depended, in part, on the status of Taiwan.

Fourth Department[edit]

The Fourth Department (ECM and Radar) of the Joint Staff Headquarters Department has the electronic intelligence (ELINT) portfolio within the PLA’s SIGINT apparatus. This department is responsible for electronic countermeasures, requiring them to collect and maintain databases on electronic signals. 25 ELINT receivers are the responsibility of the Southwest Institute of Electronic Equipment (SWIEE). Among the wide range of SWIEE ELINT products is a new KZ900 airborne ELINT pod. The GSD 54th Research Institute supports the ECM Department in the development of digital ELINT signal processors to analyze parameters of radar pulses.

Special forces[edit]

China’s special ground force is called PLASF (People’s Liberation Army Special Operations Forces). Typical units include consist of highly trained soldiers, a team commander, assistant commander, sniper, spotter, machine-gun support, bomber, and a pair of assault groups.[citation needed] China’s counter-terrorism unit members are drawn from the public security apparatus rather than the military. The name of such units change frequently. As of 2020, it is known as the Immediate Action Unit (IAU).[153]

China has reportedly developed a force capable of carrying out long-range airborne operations, long-range reconnaissance, and amphibious operations. Formed in China’s Guangzhou military region and known by the nickname «South Blade», the force supposedly receives army, air force, and naval training, including flight training, and is equipped with «hundreds of high-tech devices», including global-positioning satellite systems. All force members officers are military staff college graduates, and 60 percent are said to have university degrees.

Soldiers are reported to be cross-trained in various specialties, and training encompassing a wide range of operating environments. It is far from clear whether this unit is considered operational by the Chinese. It is also not clear how such a force would be employed. Among the missions stated missions include: «responding to contingencies in various regions» and «cooperating with other services in attacks on islands».

According to the limited reporting, the organisation appears to be in a phase of testing and development and may constitute an experimental unit. While no size for the force has been revealed, there have been Chinese media claims that «over 4,000 soldiers of the force are all-weather and versatile fighters and parachutists who can fly airplanes and drive terrain vehicles and amphibious boats».[citation needed]

Other branches[edit]

- The Third Department and the Navy co-operate on shipborne intelligence collection platforms.

- PLAAF Sixth Research Institute: Air Force SIGINT collection is managed by the PLAAF Sixth Research Institute in Beijing.

Weapons and equipment[edit]

According to the United States Department of Defense, China is developing kinetic-energy weapons, high-powered lasers, high-powered microwave weapons, particle-beam weapons, and electromagnetic pulse weapons with its increase of military fundings.[154]

The PLA has said of reports that its modernisation is dependent on sales of advanced technology from American allies, senior leadership have stated «Some have politicized China’s normal commercial cooperation with foreign countries, damaging our reputation.» These contributions include advanced European diesel engines for Chinese warships, military helicopter designs from Eurocopter, French anti-submarine sonars and helicopters,[155] Australian technology for the Houbei class missile boat,[156] and Israeli supplied American missile, laser and aircraft technology.[157]

According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute’s data, China became the world’s third largest exporter of major arms in 2010–14, an increase of 143 percent from the period 2005–2009.[158] SIPRI also calculated that China surpassed Russia to become the world’s second largest arms exporter by 2020.[159]

China’s share of global arms exports hence increased from 3 to 5 percent. China supplied major arms to 35 states in 2010–14. A significant percentage (just over 68 percent) of Chinese exports went to three countries: Pakistan, Bangladesh and Myanmar. China also exported major arms to 18 African states. Examples of China’s increasing global presence as an arms supplier in 2010–14 included deals with Venezuela for armoured vehicles and transport and trainer aircraft, with Algeria for three frigates, with Indonesia for the supply of hundreds of anti-ship missiles and with Nigeria for the supply of several unmanned combat aerial vehicles.[160]

Following rapid advances in its arms industry, China has become less dependent on arms imports, which decreased by 42 percent between 2005–09 and 2010–14. Russia accounted for 61 percent of Chinese arms imports, followed by France with 16 percent and Ukraine with 13 per cent. Helicopters formed a major part of Russian and French deliveries, with the French designs produced under licence in China.[160]

Over the years, China has struggled to design and produce effective engines for combat and transport vehicles. It continued to import large numbers of engines from Russia and Ukraine in 2010–14 for indigenously designed combat, advanced trainer and transport aircraft, and naval ships. It also produced British-, French- and German-designed engines for combat aircraft, naval ships and armoured vehicles, mostly as part of agreements that have been in place for decades.[160]

In August 2021, China tested a nuclear-capable hypersonic missile that circled the globe before speeding towards its target.[161] The Financial Times reported that «the test showed that China had made astounding progress on hypersonic weapons and was far more advanced than U.S. officials realized.»[162] During the Exercise Zapad-81 in 2021 with Russian forces, most of the gear were novel Chinese arms such as the KJ-500 airborne early warning and control aircraft, J-20 and J-16 fighters, Y-20 transport planes, and surveillance and combat drones.[163] Another joint forces exercise took place in August 2023 near Alaska.[164]

Cyberwarfare[edit]

There is a belief in the Western military doctrines that the PLA have already begun engaging countries using cyber-warfare.[165] There has been a significant increase in the number of presumed Chinese military initiated cyber events from 1999 to the present day.[166]

Cyberwarfare has gained recognition as a valuable technique because it is an asymmetric technique that is a part of information operations and information warfare. As is written by two PLAGF Colonels, Qiao Liang and Wang Xiangsui in the book Unrestricted Warfare, «Methods that are not characterized by the use of the force of arms, nor by the use of military power, nor even by the presence of casualties and bloodshed, are just as likely to facilitate the successful realization of the war’s goals, if not more so.[167]

While China has long been suspected of cyber spying, on 24 May 2011 the PLA announced the existence of having ‘cyber capabilities’.[168]

In February 2013, the media named «Comment Crew» as a hacker military faction for China’s People’s Liberation Army.[169] In May 2014, a Federal Grand Jury in the United States indicted five Unit 61398 officers on criminal charges related to cyber attacks on private companies based in the United States after alleged investigations by the Federal Bureau of Investigation who exposed their identities in collaboration with US intelligence agencies such as the CIA.[170][171]

In February 2020, the United States government indicted members of China’s People’s Liberation Army for the 2017 Equifax data breach, which involved hacking into Equifax and plundering sensitive data as part of a massive heist that also included stealing trade secrets, though the CCP denied these claims.[172][173]

Nuclear capabilities[edit]

In 1955, China decided to proceed with a nuclear weapons program. The decision was made after the United States threatened the use of nuclear weapons against China should it take action against Quemoy and Matsu, coupled with the lack of interest of the Soviet Union for using its nuclear weapons in defense of China.[citation needed]

After their first nuclear test (China claims minimal Soviet assistance before 1960) on 16 October 1964, China was the first state to pledge no-first-use of nuclear weapons. On 1 July 1966, the Second Artillery Corps, as named by Premier Zhou Enlai, was formed. In 1967, China tested a fully functional hydrogen bomb, only 32 months after China had made its first fission device. China thus produced the shortest fission-to-fusion development known in history.

China became a major international arms exporter during the 1980s. Beijing joined the Middle East arms control talks, which began in July 1991 to establish global guidelines for conventional arms transfers, and later announced that it would no longer participate because of the US decision to sell 150 F-16A/B aircraft to Taiwan on 2 September 1992.

It joined the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) in 1984 and pledged to abstain from further atmospheric testing of nuclear weapons in 1986. China acceded to the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) in 1992 and supported its indefinite and unconditional extension in 1995. Nuclear weapons tests by China ceased in 1996, when it signed the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty and agreed to seek an international ban on the production of fissile nuclear weapons material.

In 1996, China committed[clarification needed] to assisting unsafeguarded nuclear facilities.[citation needed] China attended the May 1997 meeting of the NPT Exporters (Zangger) Committee as an observer and became a full member in October 1997. The Zangger Committee is a group that meets to list items that should be subject to IAEA inspections if exported by countries, which have, as China has signed the Non-Proliferation Treaty. In September 1997, China issued detailed nuclear export control regulations.

China began implementing regulations[which?] establishing controls over nuclear-related dual-use items in 1998.[citation needed] China also has decided not to engage in new nuclear cooperation with Iran (even under safeguards) and will complete existing cooperation, which is not of proliferation concern, within a relatively short period. Based on significant, tangible progress with China on nuclear nonproliferation, President Clinton in 1998 took steps to bring into force the 1985 US-China Agreement on Peaceful Nuclear Cooperation.[citation needed]

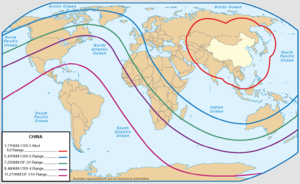

Beijing has deployed a modest ballistic missile force, including land and sea-based intermediate-range and intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs). It was estimated in 2007 that China has about 100–160 liquid-fuelled ICBMs capable of striking the United States with approximately 100–150 IRBMs able to strike Russia or Eastern Europe, as well as several hundred tactical SRBMs with ranges between 300 and 600 km.[174] Currently, the Chinese nuclear stockpile is estimated to be between 50 and 75 land and sea based ICBMs.[175]

China’s nuclear program has historically followed a doctrine of minimal deterrence, which involves having the minimum force needed to deter an aggressor from launching a first strike. The current efforts of China appear to be aimed at maintaining a survivable nuclear force by, for example, using solid-fuelled ICBMs in silos rather than liquid-fuelled missiles. China’s 2006 published deterrence policy states that they will «uphold the principles of counterattack in self-defense and limited development of nuclear weapons», but «has never entered, and will never enter into a nuclear arms race with any country». It goes on to describe that China will never undertake a first strike, or use nuclear weapons against a non-nuclear state or zone.[174]