Arvind Krishna, Chairman and Chief Executive Officer

Jonathan H. Adashek, Chief Communications Officer and Senior Vice President, Marketing and Communications

Simon J. Beaumont, Vice President, Tax and Treasurer

Michelle H. Browdy, Senior Vice President, Legal and Regulatory Affairs, and General Counsel

Kelly C. Chambliss, Senior Vice President and Chief Operating Officer, IBM Consulting

Gary D. Cohn, Vice Chairman

Nicolas A. Fehring, Vice President and Controller

Darío Gil, Senior Vice President and Director IBM Research

John Granger, Senior Vice President, IBM Consulting

James J. Kavanaugh, Senior Vice President and Chief Financial Officer

Sebastian Krause, Senior Vice President and Chief Revenue Officer

Nickle J. LaMoreaux, Senior Vice President and Chief Human Resources Officer

Ric Lewis, Senior Vice President, Infrastructure

Robert W. Lord, Senior Vice President, The Weather Company and Alliances

Dinesh Nirmal, Senior Vice President, Products, IBM Software

Paul Papas, Senior Vice President, IBM Consulting, Americas

Frank Sedlarcik, Vice President, Assistant General Counsel and Secretary

Alexander F. Stern, Senior Vice President, Strategy and M&A

Robert D. Thomas, Senior Vice President, Software and Chief Commercial Officer

Joanne Wright, Senior Vice President, Transformation and Operations

Kareem Yusuf, Ph.D, Senior Vice President, Product Management and Growth, IBM Software

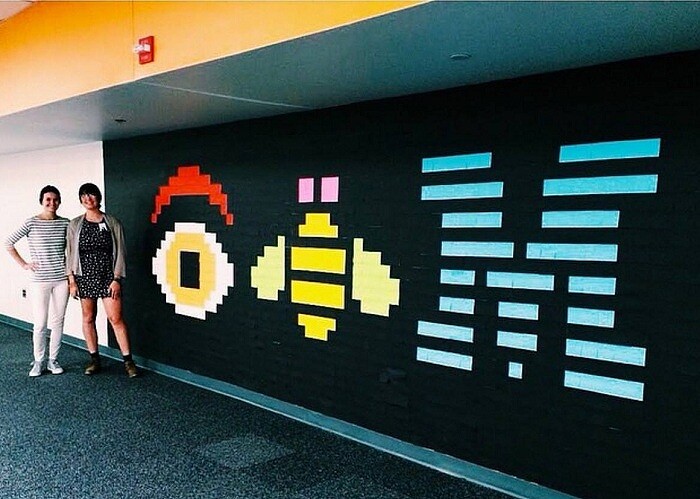

Logo since 1972, designed by Paul Rand |

|

|

Trade name |

IBM |

|---|---|

| Formerly | Computing-Tabulating-Recording Company (1911-1924) |

| Type | Public |

|

Traded as |

|

| ISIN | US4592001014 |

| Industry | Information technology |

| Predecessors | Bundy Manufacturing Company Computing Scale Company of America International Time Recording Company Tabulating Machine Company Computing-Tabulating-Recording Company |

| Founded | June 16, 1911; 112 years ago (as Computing-Tabulating-Recording Company) Endicott, New York, U.S.[1] |

| Founders | Herman Hollerith Charles Ranlett Flint Thomas J. Watson, Sr. |

| Headquarters | 1 Orchard Road,

Armonk, New York , United States |

|

Area served |

177 countries[2] |

|

Key people |

|

| Products | Automation Robotics Artificial intelligence Cloud computing Consulting Blockchain Computer hardware Software Quantum computing |

| Brands |

|

| Services |

|

| Revenue | |

|

Operating income |

|

|

Net income |

|

| Total assets | |

| Total equity | |

|

Number of employees |

288,300 (December 2022)[5] |

| Subsidiaries | List of subsidiaries |

| Website | www |

The International Business Machines Corporation (doing business as IBM), nicknamed Big Blue,[6] is an American multinational technology corporation headquartered in Armonk, New York and is present in over 175 countries.[7][8] It specializes in computer hardware, middleware, and software, and provides hosting and consulting services in areas ranging from mainframe computers to nanotechnology. IBM is the largest industrial research organization in the world, with 19 research facilities across a dozen countries, and has held the record for most annual U.S. patents generated by a business for 29 consecutive years from 1993 to 2021.[9][10][11]

IBM was founded in 1911 as the Computing-Tabulating-Recording Company (CTR), a holding company of manufacturers of record-keeping and measuring systems. It was renamed «International Business Machines» in 1924 and soon became the leading manufacturer of punch-card tabulating systems. For the next several decades, IBM would become an industry leader in several emerging technologies, including electric typewriters, electromechanical calculators, and personal computers. During the 1960s and 1970s, the IBM mainframe, exemplified by the System/360, was the dominant computing platform, and the company produced 80 percent of computers in the U.S. and 70 percent of computers worldwide.[12]

After pioneering the multipurpose microcomputer in the 1980s, which set the standard for personal computers, IBM began losing its market dominance to emerging competitors. Beginning in the 1990s, the company began downsizing its operations and divesting from commodity production, most notably selling its personal computer division to the Lenovo Group in 2005. IBM has since concentrated on computer services, software, supercomputers, and scientific research. Since 2000, its supercomputers have consistently ranked among the most powerful in the world, and in 2001 it became the first company to generate more than 3,000 patents in one year, beating this record in 2008 with over 4,000 patents.[12] As of 2022, the company held 150,000 patents.[13]

As one of the world’s oldest and largest technology companies, IBM has been responsible for several technological innovations, including the automated teller machine (ATM), dynamic random-access memory (DRAM), the floppy disk, the hard disk drive, the magnetic stripe card, the relational database, the SQL programming language, and the UPC barcode. The company has made inroads in advanced computer chips, quantum computing, artificial intelligence, and data infrastructure. IBM employees and alumni have won various recognitions for their scientific research and inventions, including six Nobel Prizes and six Turing Awards.[14]

IBM is a publicly traded company and one of 30 companies in the Dow Jones Industrial Average. It is among the world’s largest employers, with over 297,900 employees worldwide in 2022.[15] Despite its relative decline within the technology sector,[16] IBM remains the seventh largest technology company by revenue, and 49th largest overall, according to the 2022 Fortune 500.[15] It is also consistently ranked among the world’s most recognizable, valuable, and admired brands.[17]

History[edit]

IBM was founded in 1911 in Endicott, New York; as the Computing-Tabulating-Recording Company (CTR) and was renamed «International Business Machines» in 1924.[18] IBM is incorporated in New York and has operations in over 170 countries.[8]

In the 1880s, technologies emerged that would ultimately form the core of International Business Machines (IBM). Julius E. Pitrap patented the computing scale in 1885;[19] Alexander Dey invented the dial recorder (1888);[20] Herman Hollerith (1860–1929) patented the Electric Tabulating Machine;[21] and Willard Bundy invented a time clock to record workers’ arrival and departure times on a paper tape in 1889.[22] On June 16, 1911, their four companies were amalgamated in New York State by Charles Ranlett Flint forming a fifth company, the Computing-Tabulating-Recording Company (CTR) based in Endicott, New York.[1][23] The five companies had 1,300 employees and offices and plants in Endicott and Binghamton, New York; Dayton, Ohio; Detroit, Michigan; Washington, D.C.; and Toronto.[citation needed]

They manufactured machinery for sale and lease, ranging from commercial scales and industrial time recorders, meat and cheese slicers, to tabulators and punched cards. Thomas J. Watson, Sr., fired from the National Cash Register Company by John Henry Patterson, called on Flint and, in 1914, was offered a position at CTR.[24] Watson joined CTR as general manager and then, 11 months later, was made President when antitrust cases relating to his time at NCR were resolved.[25] Having learned Patterson’s pioneering business practices, Watson proceeded to put the stamp of NCR onto CTR’s companies.[26] He implemented sales conventions, «generous sales incentives, a focus on customer service, an insistence on well-groomed, dark-suited salesmen and had an evangelical fervor for instilling company pride and loyalty in every worker».[27][28] His favorite slogan, «THINK», became a mantra for each company’s employees.[27] During Watson’s first four years, revenues reached $9 million ($152 million today) and the company’s operations expanded to Europe, South America, Asia and Australia.[27] Watson never liked the clumsy hyphenated name «Computing-Tabulating-Recording Company» and on February 14, 1924, chose to replace it with the more expansive title «International Business Machines» which had previously been used as the name of CTR’s Canadian Division.[29] By 1933, most of the subsidiaries had been merged into one company, IBM.[30]

The Nazis reportedly made extensive use of Hollerith punch card and alphabetical accounting equipment and IBM’s majority-owned German subsidiary, Deutsche Hollerith Maschinen GmbH (Dehomag), supplied this equipment from the early 1930s. This equipment was critical to Nazi efforts to categorize citizens of both Germany and other nations that fell under Nazi control through ongoing censuses. This census data was used to facilitate the round-up of Jews and other targeted groups, and to catalog their movements through the machinery of the Holocaust, including internment in the concentration camps.[31] Nazi concentration camps operate a Hollerith department called Hollerith Abteilung, which had IBM machineries that also included calculating and sorting machines.[32] There is much debate amongst the history community about whether IBM was complicit in the use of these machines, whether the machines used were IBM branded, and even whether tabulating machines were used for this purpose at all.[33]

IBM has several leadership development and recognition programs to acknowledge and foster employee potential and achievements. For early-career high potential employees, IBM sponsors leadership development programs by discipline (e.g., general management (GMLDP), human resources (HRLDP), finance (FLDP)). Each year, the company also selects 500 IBM employees for the IBM Corporate Service Corps (CSC),[34] which gives top employees a month to do humanitarian work abroad.[35] For certain interns, IBM also has a program called Extreme Blue that partners top business and technical students to develop high-value technology and compete to present their business case to the company’s CEO at internship’s end.[36]

The company also has various designations for exceptional individual contributors such as Senior Technical Staff Member (STSM), Research Staff Member (RSM), Distinguished Engineer (DE), and Distinguished Designer (DD).[37] Prolific inventors can also achieve patent plateaus and earn the designation of Master Inventor. The company’s most prestigious designation is that of IBM Fellow. Since 1963, the company names a handful of Fellows each year based on technical achievement. Other programs recognize years of service such as the Quarter Century Club established in 1924, and sellers are eligible to join the Hundred Percent Club, composed of IBM salesmen who meet their quotas, convened in Atlantic City, New Jersey. Each year, the company also selects 1,000 IBM employees annually to award the Best of IBM Award, which includes an all-expenses-paid trip to the awards ceremony in an exotic location.

IBM built the Automatic Sequence Controlled Calculator, an electromechanical computer, during World War II. It offered its first commercial stored-program computer, the vacuum tube based IBM 701, in 1952. The IBM 305 RAMAC introduced the hard disk drive in 1956. The company switched to transistorized designs with the 7000 and 1400 series, beginning in 1958.

In 1956, the company demonstrated the first practical example of artificial intelligence when Arthur L. Samuel of IBM’s Poughkeepsie, New York, laboratory programmed an IBM 704 not merely to play checkers but «learn» from its own experience. In 1957, the FORTRAN scientific programming language was developed. In 1961, IBM developed the SABRE reservation system for American Airlines and introduced the highly successful Selectric typewriter.

In 1963, IBM employees and computers helped NASA track the orbital flights of the Mercury astronauts. A year later, it moved its corporate headquarters from New York City to Armonk, New York. The latter half of the 1960s saw IBM continue its support of space exploration, participating in the 1965 Gemini flights, 1966 Saturn flights, and 1969 lunar mission. IBM also developed and manufactured the Saturn V’s Instrument Unit and Apollo spacecraft guidance computers.

On April 7, 1964, IBM launched the first computer system family, the IBM System/360. It spanned the complete range of commercial and scientific applications from large to small, allowing companies for the first time to upgrade to models with greater computing capability without having to rewrite their applications. It was followed by the IBM System/370 in 1970. Together the 360 and 370 made the IBM mainframe the dominant mainframe computer and the dominant computing platform in the industry throughout this period and into the early 1980s. They and the operating systems that ran on them such as OS/VS1 and MVS, and the middleware built on top of those such as the CICS transaction processing monitor, had a near-monopoly-level market share and became the thing IBM was most known for during this period.[38]

In 1969, the United States of America alleged that IBM violated the Sherman Antitrust Act by monopolizing or attempting to monopolize the general-purpose electronic digital computer system market, specifically computers designed primarily for business, and subsequently alleged that IBM violated the antitrust laws in IBM’s actions directed against leasing companies and plug-compatible peripheral manufacturers. Shortly after, IBM unbundled its software and services in what many observers believed was a direct result of the lawsuit, creating a competitive market for software. In 1982, the Department of Justice dropped the case as «without merit».[39]

Also in 1969, IBM engineer Forrest Parry invented the magnetic stripe card that would become ubiquitous for credit/debit/ATM cards, driver’s licenses, rapid transit cards, and a multitude of other identity and access control applications. IBM pioneered the manufacture of these cards, and for most of the 1970s, the data processing systems and software for such applications ran exclusively on IBM computers. In 1974, IBM engineer George J. Laurer developed the Universal Product Code.[40] IBM and the World Bank first introduced financial swaps to the public in 1981, when they entered into a swap agreement.[41] The IBM PC, originally designated IBM 5150, was introduced in 1981, and it soon became an industry standard.

In 1991 IBM began spinning off its many divisions into autonomous subsidiaries (so-called «Baby Blues») in an attempt to make the company more manageable and to streamline IBM by having other investors finance those companies.[42][43] These included AdStar, dedicated to disk drives and other data storage products; IBM Application Business Systems, dedicated to mid-range computers; IBM Enterprise Systems, dedicated to mainframes; Pennant Systems, dedicated to mid-range and large printers; Lexmark, dedicated to small printers; and more.[44] Lexmark was acquired by Clayton & Dubilier in a leveraged buyout shortly after its formation.[45]

In September 1992, IBM completed the spin-off of their various non-mainframe and non-midrange, personal computer manufacturing divisions, combining them into an autonomous wholly owned subsidiary known as the IBM Personal Computer Company (IBM PC Co.).[46][47] This corporate restructuring came after IBM reported a sharp drop in profit margins during the second quarter of fiscal year 1992; market analysts attributed the drop to a fierce price war in the personal computer market over the summer of 1992.[48] The corporate restructuring was one of the largest and most expensive in history up to that point.[49] By the summer of 1993, the IBM PC Co. had divided into multiple business units itself, including Ambra Computer Corporation and the IBM Power Personal Systems Group, the former an attempt to design and market «clone» computers of IBM’s own architecture and the latter responsible for IBM’s PowerPC-based workstations.[50][51]

In 1993, IBM posted an $8 billion loss – at the time the biggest in American corporate history.[52] Lou Gerstner was hired as CEO from RJR Nabisco to turn the company around.[53] In 2002 IBM acquired PwC Consulting, the consulting arm of PwC which was merged into its IBM Global Services.[54][55]

In 1998, IBM merged the enterprise-oriented Personal Systems Group of the IBM PC Co. into IBM’s own Global Services personal computer consulting and customer service division. The resulting merged business units then became known simply as IBM Personal Systems Group.[56] In 1999, IBM stopped selling their computers at retail outlets after their market share in this sector had fallen considerably behind competitors Compaq and Dell.[57] Immediately afterwards, the IBM PC Co. was dissolved and merged into IBM Personal Systems Group.[58]

On September 14, 2004, LG and IBM announced that their business alliance in the South Korean market would end at the end of that year. Both companies stated that it was unrelated to the charges of bribery earlier that year.[59][60][61][62] Xnote was originally part of the joint venture and was sold by LG in 2012.[63]

In 2005, the company sold all of its personal computer business to Chinese technology company Lenovo[64] and, in 2009, it acquired software company SPSS Inc. Later in 2009, IBM’s Blue Gene supercomputing program was awarded the National Medal of Technology and Innovation by U.S. President Barack Obama. In 2011, IBM gained worldwide attention for its artificial intelligence program Watson, which was exhibited on Jeopardy! where it won against game-show champions Ken Jennings and Brad Rutter. The company also celebrated its 100th anniversary in the same year on June 16. In 2012, IBM announced it had agreed to buy Kenexa and Texas Memory Systems,[65] and a year later it also acquired SoftLayer Technologies, a web hosting service, in a deal worth around $2 billion.[66] Also that year, the company designed a video surveillance system for Davao City.[67]

In 2014, IBM announced it would sell its x86 server division to Lenovo for $2.1 billion.[68][better source needed] while continuing to offer Power ISA-based servers. Also that year, IBM began announcing several major partnerships with other companies, including Apple Inc.,[69][70] Twitter,[71] Facebook,[72] Tencent,[73] Cisco,[74] UnderArmour,[75] Box,[76] Microsoft,[77] VMware,[78] CSC,[79] Macy’s,[80] Sesame Workshop,[81] the parent company of Sesame Street, and Salesforce.com.[82]

In 2015, IBM announced three major acquisitions: Merge Healthcare for $1 billion,[83] data storage vendor Cleversafe, and all digital assets from The Weather Company, including Weather.com and the Weather Channel mobile app.[84][85] Also that year, IBM employees created the film A Boy and His Atom, which was the first molecule movie to tell a story. In 2016, IBM acquired video conferencing service Ustream and formed a new cloud video unit.[86][87] In April 2016, it posted a 14-year low in quarterly sales.[88] The following month, Groupon sued IBM accusing it of patent infringement, two months after IBM accused Groupon of patent infringement in a separate lawsuit.[89]

In 2015, IBM bought the digital part of The Weather Company,[90] Truven Health Analytics for $2.6 billion in 2016, and in October 2018, IBM announced its intention to acquire Red Hat for $34 billion,[91][92][93] which was completed on July 9, 2019.[94]

IBM announced in October 2020 that it would divest the Managed Infrastructure Services unit of its Global Technology Services division into a new public company.[95] The new company, Kyndryl, will have 90,000 employees, 4,600 clients in 115 countries, with a backlog of $60 billion.[96][97][98] IBM’s spin off was greater than any of its previous divestitures, and welcomed by investors.[99][100][101] IBM appointed Martin Schroeter, who had been IBM’s CFO from 2014 through the end of 2017, as CEO of Kyndryl.[102][103]

On March 7, 2022, a few days after the start of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, IBM CEO Arvind Krishna published a Ukrainian flag and announced that «we have suspended all business in Russia». All Russian articles were also removed from the IBM website.[104] On June 7, Krishna announced that IBM would carry out an «orderly wind-down» of its operations in Russia.[105]

Headquarters and offices[edit]

IBM is headquartered in Armonk, New York, a community 37 miles (60 km) north of Midtown Manhattan.[106] A nickname for the company is the «Colossus of Armonk«.[107] Its principal building, referred to as CHQ, is a 283,000-square-foot (26,300 m2) glass and stone edifice on a 25-acre (10 ha) parcel amid a 432-acre former apple orchard the company purchased in the mid-1950s.[108] There are two other IBM buildings within walking distance of CHQ: the North Castle office, which previously served as IBM’s headquarters; and the Louis V. Gerstner, Jr., Center for Learning[109] (formerly known as IBM Learning Center (ILC)), a resort hotel and training center, which has 182 guest rooms, 31 meeting rooms, and various amenities.[110]

IBM operates in 174 countries as of 2016,[2] with mobility centers in smaller market areas and major campuses in the larger ones. In New York City, IBM has several offices besides CHQ, including the IBM Watson headquarters at Astor Place in Manhattan. Outside of New York, major campuses in the United States include Austin, Texas; Research Triangle Park (Raleigh-Durham), North Carolina; Rochester, Minnesota; and Silicon Valley, California.

IBM’s real estate holdings are varied and globally diverse. Towers occupied by IBM include 1250 René-Lévesque (Montreal, Canada) and One Atlantic Center (Atlanta, Georgia, US). In Beijing, China, IBM occupies Pangu Plaza,[111] the city’s seventh tallest building and overlooking Beijing National Stadium («Bird’s Nest»), home to the 2008 Summer Olympics.

IBM India Private Limited is the Indian subsidiary of IBM, which is headquartered at Bangalore, Karnataka. It has facilities in Coimbatore, Chennai, Kochi, Ahmedabad, Delhi, Kolkata, Mumbai, Pune, Gurugram, Noida, Bhubaneshwar, Surat, Visakhapatnam, Hyderabad, Bangalore and Jamshedpur.

Other notable buildings include the IBM Rome Software Lab (Rome, Italy), Hursley House (Winchester, UK), 330 North Wabash (Chicago, Illinois, United States), the Cambridge Scientific Center (Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States), the IBM Toronto Software Lab (Toronto, Canada), the IBM Building, Johannesburg (Johannesburg, South Africa), the IBM Building (Seattle) (Seattle, Washington, United States), the IBM Hakozaki Facility (Tokyo, Japan), the IBM Yamato Facility (Yamato, Japan), the IBM Canada Head Office Building (Ontario, Canada) and the Watson IoT Headquarters[112] (Munich, Germany). Defunct IBM campuses include the IBM Somers Office Complex (Somers, New York), Spango Valley (Greenock, Scotland), and Tour Descartes (Paris, France). The company’s contributions to industrial architecture and design include works by Marcel Breuer, Eero Saarinen, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, I.M. Pei and Ricardo Legorreta. Van der Rohe’s building in Chicago was recognized with the 1990 Honor Award from the National Building Museum.[113]

IBM was recognized as one of the Top 20 Best Workplaces for Commuters by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in 2005, which recognized Fortune 500 companies that provided employees with excellent commuter benefits to help reduce traffic and air pollution.[114] In 2004, concerns were raised related to IBM’s contribution in its early days to pollution in its original location in Endicott, New York.[115][116]

Finance[edit]

| Year | Revenue in mil. US$ |

Net income in mil. US$ |

Employees |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | 102,874 |

16,604 | 434,246 |

| 2013 | 98,367 |

16,483 | 431,212 |

| 2014 | 92,793 |

12,022 | 379,592 |

| 2015 | 81,741 |

13,190 | 377,757 |

| 2016 | 79,919 |

11,872 | 380,300 |

| 2017 | 79,139 |

5,753 | 366,600 |

| 2018 | 79,591 |

8,723 | 350,600 |

| 2019 | 77,100 |

9,400 | 352,600 |

| 2020 | 73,620 |

5,590 | 345,900 |

| 2021 | 57,350† |

5,743 | 282,100 |

| 2022 | 60,530 |

1,639 | 288,300 |

For the fiscal year 2020, IBM reported earnings of $5.6 billion, with an annual revenue of $73.6 billion. IBM’s revenue has fallen for 8 of the last 9 years.[117] IBM’s market capitalization was valued at over $127 billion as of April 2021.[118] IBM ranked No. 38 on the 2020 Fortune 500 rankings of the largest United States corporations by total revenue.[119] In 2014, IBM was accused of using «financial engineering» to hit its quarterly earnings targets rather than investing for the longer term.[120][121][122]

Products and services[edit]

IBM has a large and diverse portfolio of products and services. As of 2016, these offerings fall into the categories of cloud computing, artificial intelligence, commerce, data and analytics, Internet of things (IoT),[123] IT infrastructure, mobile, digital workplace[124] and cybersecurity.[125]

IBM Cloud includes infrastructure as a service (IaaS), software as a service (SaaS) and platform as a service (PaaS) offered through public, private and hybrid cloud delivery models. For instance, the IBM Bluemix PaaS enables developers to quickly create complex websites on a pay-as-you-go model. IBM SoftLayer is a dedicated server, managed hosting and cloud computing provider, which in 2011 reported hosting more than 81,000 servers for more than 26,000 customers.[126] IBM also provides Cloud Data Encryption Services (ICDES), using cryptographic splitting to secure customer data.[127]

IBM also hosts the industry-wide cloud computing and mobile technologies conference InterConnect each year.[128]

Hardware designed by IBM for these categories include IBM’s Power microprocessors, which are employed inside many console gaming systems, including Xbox 360,[129] PlayStation 3, and Nintendo’s Wii U.[130][131] IBM Secure Blue is encryption hardware that can be built into microprocessors,[132] and in 2014, the company revealed TrueNorth, a neuromorphic CMOS integrated circuit and announced a $3 billion investment over the following five years to design a neural chip that mimics the human brain, with 10 billion neurons and 100 trillion synapses, but that uses just 1 kilowatt of power.[133] In 2016, the company launched all-flash arrays designed for small and midsized companies, which includes software for data compression, provisioning, and snapshots across various systems.[134]

IT outsourcing also represents a major service provided by IBM, with more than 60 data centers worldwide.[135] alphaWorks is IBM’s source for emerging software technologies, and SPSS is a software package used for statistical analysis. IBM’s Kenexa suite provides employment and retention solutions[buzzword], and includes the BrassRing, an applicant tracking system used by thousands of companies for recruiting.[136] IBM also owns The Weather Company, which provides weather forecasting and includes weather.com and Weather Underground.[137]

Smarter Planet is an initiative that seeks to achieve economic growth, near-term efficiency, sustainable development, and societal progress,[138][139] targeting opportunities such as smart grids,[140] water management systems,[141] solutions to traffic congestion,[142] and greener buildings.[143]

Services provisions include Redbooks, which are publicly available online books about best practices with IBM products, and developerWorks, a website for software developers and IT professionals with how-to articles and tutorials, as well as software downloads, code samples, discussion forums, podcasts, blogs, wikis, and other resources for developers and technical professionals.[144]

IBM Watson is a technology platform that uses natural language processing and machine learning to reveal insights from large amounts of unstructured data.[145] Watson was debuted in 2011 on the American gameshow Jeopardy!, where it competed against champions Ken Jennings and Brad Rutter in a three-game tournament and won. Watson has since been applied to business, healthcare, developers, and universities. For example, IBM has partnered with Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center to assist with considering treatment options for oncology patients and for doing melanoma screenings.[146] Also, several companies have begun using Watson for call centers, either replacing or assisting customer service agents.[147]

In January 2019, IBM introduced its first commercial quantum computer IBM Q System One.[148]

IBM also provides infrastructure for the New York City Police Department through their IBM Cognos Analytics to perform data visualizations of CompStat crime data.[149]

In March 2020, it was announced that IBM will build the first quantum computer in Germany. The computer should allow researchers to harness the technology without falling foul of the EU’s increasingly assertive stance on data sovereignty.[150]

In June 2020, IBM announced that it was exiting the facial recognition business. In a letter to congress,[151] IBM’s Chief Executive Officer Arvind Krishna told lawmakers, «now is the time to begin a national dialogue on whether and how facial recognition technology should be employed by domestic law enforcement agencies.»[152]

In May 2022, IBM announced the company had signed a multi-year Strategic Collaboration Agreement with Amazon Web Services to make a wide variety of IBM software available as a service on AWS Marketplace. Additionally, the deal includes both companies making joint investments that make it easier for companies to consume IBM’s offering and integrate them with AWS, including developer training and software development for select markets.[153]

In November 2022, the company came out with a chip called the 433-qubit Osprey. Time called it «the world’s most powerful quantum processor» and noted that if the processor’s speed were represented in bits, the number would be larger than the total number of atoms in the universe.[154]

In an effort to streamline its products and services, beginning in the 1990s, IBM has regularly sold off low margin assets while shifting its focus to higher-value, more profitable markets. In 1991, the company spun off its printer and keyboard manufacturing division to Lexmark, in 2005 it sold its personal computer (ThinkPad/ThinkCentre) business to Lenovo, in 2015 it adopted a «fabless» model with semiconductors design and offloaded manufacturing to GlobalFoundries, and in 2021 it spun-off its managed infrastructure services unit into a new public company named Kyndryl.[155][156] IBM also announced the acquisition of the enterprise software company Turbonomic for $1.5 billion.[157] In 2022, IBM announced it would sell Watson Health to private equity firm Francisco Partners.[158] IBM also started a collaboration with new Japanese manufacturer Rapidus in late 2022,[159] which led GlobalFoundries to file a lawsuit against IBM the following year.[160]

Research[edit]

Research has been part of IBM since its founding, and its organized efforts trace their roots back to 1945, when the Watson Scientific Computing Laboratory was founded at Columbia University in New York City, converting a renovated fraternity house on Manhattan’s West Side into IBM’s first laboratory. Now, IBM Research constitutes the largest industrial research organization in the world, with 12 labs on 6 continents.[161] IBM Research is headquartered at the Thomas J. Watson Research Center in New York, and facilities include the Almaden lab in California, Austin lab in Texas, Australia lab in Melbourne, Brazil lab in São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, China lab in Beijing and Shanghai, Ireland lab in Dublin, Haifa lab in Israel, India lab in Delhi and Bangalore, Tokyo lab, Zurichlab and Africa lab in Nairobi.

In terms of investment, IBM’s R&D expenditure totals several billion dollars each year. In 2012, that expenditure was approximately $6.9 billion.[162] Recent allocations have included $1 billion to create a business unit for Watson in 2014, and $3 billion to create a next-gen semiconductor along with $4 billion towards growing the company’s «strategic imperatives» (cloud, analytics, mobile, security, social) in 2015.[163]

IBM has been a leading proponent of the Open Source Initiative, and began supporting Linux in 1998.[164] The company invests billions of dollars in services and software based on Linux through the IBM Linux Technology Center, which includes over 300 Linux kernel developers.[165] IBM has also released code under different open-source licenses, such as the platform-independent software framework Eclipse (worth approximately $40 million at the time of the donation),[166] the three-sentence International Components for Unicode (ICU) license, and the Java-based relational database management system (RDBMS) Apache Derby. IBM’s open source involvement has not been trouble-free, however (see SCO v. IBM).

Famous inventions and developments by IBM include: the automated teller machine (ATM), dynamic random access memory (DRAM), the electronic keypunch, the financial swap, the floppy disk, the hard disk drive, the magnetic stripe card, the relational database, RISC, the SABRE airline reservation system, SQL, the Universal Product Code (UPC) bar code, and the virtual machine. Additionally, in 1990 company scientists used a scanning tunneling microscope to arrange 35 individual xenon atoms to spell out the company acronym, marking the first structure assembled one atom at a time.[167] A major part of IBM research is the generation of patents. Since its first patent for a traffic signaling device, IBM has been one of the world’s most prolific patent sources. In 2021, the company held the record for most patents generated by a business for 29 consecutive years for the achievement.[9]

Five IBM employees have received the Nobel Prize: Leo Esaki, of the Thomas J. Watson Research Center in Yorktown Heights, N.Y., in 1973, for work in semiconductors; Gerd Binnig and Heinrich Rohrer, of the Zurich Research Center, in 1986, for the scanning tunneling microscope;[168] and Georg Bednorz and Alex Müller, also of Zurich, in 1987, for research in superconductivity. Six IBM employees have won the Turing Award, including the first female recipient Frances E. Allen.[169] Ten National Medals of Technology (USA) and five National Medals of Science (USA) have been awarded to IBM employees.

Brand and reputation[edit]

IBM is nicknamed Big Blue partly due to its blue logo and color scheme,[170][171] and also in reference to its former de facto dress code of white shirts with blue suits.[170][172] The company logo has undergone several changes over the years, with its current «8-bar» logo designed in 1972 by graphic designer Paul Rand.[173] It was a general replacement for a 13-bar logo, since period photocopiers did not render narrow (as opposed to tall) stripes well. Aside from the logo, IBM used Helvetica as a corporate typeface for 50 years, until it was replaced in 2017 by the custom-designed IBM Plex.

IBM has a valuable brand as a result of over 100 years of operations and marketing campaigns. Since 1996, IBM has been the exclusive technology partner for the Masters Tournament, one of the four major championships in professional golf, with IBM creating the first Masters.org (1996), the first course cam (1998), the first iPhone app with live streaming (2009), and first-ever live 4K Ultra High Definition feed in the United States for a major sporting event (2016).[174] As a result, IBM CEO Ginni Rometty became the third female member of the Master’s governing body, the Augusta National Golf Club.[175] IBM is also a major sponsor in professional tennis, with engagements at the U.S. Open, Wimbledon, the Australian Open, and the French Open.[176] The company also sponsored the Olympic Games from 1960 to 2000,[177] and the National Football League from 2003 to 2012.[178]

In 2012, IBM’s brand was valued at $75.5 billion and ranked by Interbrand as the third-best brand worldwide.[179] That same year, it was also ranked the top company for leaders (Fortune), the number two green company in the U.S. (Newsweek),[180] the second-most respected company (Barron’s),[181] the fifth-most admired company (Fortune), the 18th-most innovative company (Fast Company), and the number one in technology consulting and number two in outsourcing (Vault).[182] In 2015, Forbes ranked IBM as the fifth-most valuable brand,[183] and for 2020, the Drucker Institute named IBM the No. 3 best-managed company.[184] During the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, IBM donated $250,000 to Polish Humanitarian Action and the same amount to People in Need, Czech Republic.[185]

In terms of ESG, IBM reported its total CO2e emissions (direct and indirect) for the twelve months ending December 31, 2020 at 621 kilotons (-324 /-34.3% year-on-year).[186] In February 2021, IBM committed to achieve net zero greenhouse gas emissions by the year 2030.[187]

People and culture[edit]

Employees[edit]

IBM has one of the largest workforces in the world, and employees at Big Blue are referred to as «IBMers». The company was among the first corporations to provide group life insurance (1934), survivor benefits (1935), training for women (1935), paid vacations (1937), and training for disabled people (1942). IBM hired its first black salesperson in 1946, and in 1952, CEO Thomas J. Watson, Jr. published the company’s first written equal opportunity policy letter, one year before the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Brown vs. Board of Education and 11 years before the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The Human Rights Campaign has rated IBM 100% on its index of gay-friendliness every year since 2003,[188] with IBM providing same-sex partners of its employees with health benefits and an anti-discrimination clause. Additionally, in 2005, IBM became the first major company in the world to formally commit to not using genetic information in employment decisions. In 2017, IBM was named to Working Mother‘s 100 Best Companies List for the 32nd consecutive year.[189]

IBM has several leadership development and recognition programs to recognize employee potential and achievements. For early-career high potential employees, IBM sponsors leadership development programs by discipline (e.g., general management (GMLDP), human resources (HRLDP), finance (FLDP)). Each year, the company also selects 500 IBM employees for the IBM Corporate Service Corps (CSC),[190] which gives top employees a month to do humanitarian work abroad.[35] For certain interns, IBM also has a program called Extreme Blue that partners with top business and technical students to develop high-value technology and compete to present their business case to the company’s CEO at internship’s end.[191]

The company also has various designations for exceptional individual contributors such as Senior Technical Staff Member (STSM), Research Staff Member (RSM), Distinguished Engineer (DE), and Distinguished Designer (DD).[37] Prolific inventors can also achieve patent plateaus and earn the designation of Master Inventor. The company’s most prestigious designation is that of IBM Fellow. Since 1963, the company names a handful of Fellows each year based on technical achievement. Other programs recognize years of service such as the Quarter Century Club established in 1924, and sellers are eligible to join the Hundred Percent Club, composed of IBM salesmen who meet their quotas, convened in Atlantic City, New Jersey. Each year, the company also selects 1,000 IBM employees annually to award the Best of IBM Award, which includes an all-expenses-paid trip to the awards ceremony in an exotic location.

IBM’s culture has evolved significantly over its century of operations. In its early days, a dark (or gray) suit, white shirt, and a «sincere» tie constituted the public uniform for IBM employees.[192] During IBM’s management transformation in the 1990s, CEO Louis V. Gerstner Jr. relaxed these codes, normalizing the dress and behavior of IBM employees.[193] The company’s culture has also given to different plays on the company acronym (IBM), with some saying it stands for «I’ve Been Moved» due to relocations and layoffs,[194] others saying it stands for «I’m By Myself» pursuant to a prevalent work-from-anywhere norm,[195] and others saying it stands for «I’m Being Mentored» due to the company’s open door policy and encouragement for mentoring at all levels.[196] In terms of labor relations, the company has traditionally resisted labor union organizing,[197] although unions represent some IBM workers outside the United States.[198] In Japan, IBM employees also have an American football team complete with pro stadium, cheerleaders and televised games, competing in the Japanese X-League as the «Big Blue».[199]

In 2015, IBM started giving employees the option of choosing Mac as their primary work device, next to the option of a PC or a Linux distribution.[200] In 2016, IBM eliminated forced rankings and changed its annual performance review system to focus more on frequent feedback, coaching, and skills development.[201]

IBM alumni[edit]

Many IBM employees have achieved notability outside of work and after leaving IBM. In business, former IBM employees include Apple Inc. CEO Tim Cook,[202] former EDS CEO and politician Ross Perot, Microsoft chairman John W. Thompson, SAP co-founder Hasso Plattner, Gartner founder Gideon Gartner, Advanced Micro Devices (AMD) CEO Lisa Su,[203] Cadence Design Systems CEO Anirudh Devgan,[204] former Citizens Financial Group CEO Ellen Alemany, former Yahoo! chairman Alfred Amoroso, former AT&T CEO C. Michael Armstrong, former Xerox Corporation CEOs David T. Kearns and G. Richard Thoman,[205] former Fair Isaac Corporation CEO Mark N. Greene,[206] Citrix Systems co-founder Ed Iacobucci, ASOS.com chairman Brian McBride, former Lenovo CEO Steve Ward, and former Teradata CEO Kenneth Simonds.

In government, alumna Patricia Roberts Harris served as United States Secretary of Housing and Urban Development, the first African American woman to serve in the United States Cabinet.[207] Samuel K. Skinner served as U.S. Secretary of Transportation and as the White House Chief of Staff. Alumni also include U.S. Senators Mack Mattingly and Thom Tillis; Wisconsin governor Scott Walker;[208] former U.S. Ambassadors Vincent Obsitnik (Slovakia), Arthur K. Watson (France), and Thomas Watson Jr. (Soviet Union); and former U.S. Representatives Todd Akin,[209] Glenn Andrews, Robert Garcia, Katherine Harris,[210] Amo Houghton, Jim Ross Lightfoot, Thomas J. Manton, Donald W. Riegle Jr., and Ed Zschau.

Other former IBM employees include NASA astronaut Michael J. Massimino, Canadian astronaut and former Governor General Julie Payette, noted musician Dave Matthews,[211] Harvey Mudd College president Maria Klawe, Western Governors University president emeritus Robert Mendenhall, former University of Kentucky president Lee T. Todd Jr., NFL referee Bill Carollo,[212] former Rangers F.C. chairman John McClelland, and recipient of the Nobel Prize in Literature J. M. Coetzee. Thomas Watson Jr. also served as the 11th national president of the Boy Scouts of America.

Board and shareholders[edit]

The company’s 15-member board of directors are responsible for overall corporate management and includes the current or former CEOs of Anthem, Dow Chemical, Johnson and Johnson, Royal Dutch Shell, UPS, and Vanguard as well as the president of Cornell University and a retired U.S. Navy admiral.[213]

In 2011, IBM became the first technology company Warren Buffett’s holding company Berkshire Hathaway invested in.[214] Initially he bought 64 million shares costing $10.5 billion. Over the years, Buffet increased his IBM holdings, but by the end of 2017 had reduced them by 94.5% to 2.05 million shares; by May 2018, he was completely out of IBM.[215]

See also[edit]

- IBM SkillsBuild

- List of electronics brands

- List of largest Internet companies

- List of largest manufacturing companies by revenue

- Tech companies in the New York City metropolitan region

- Top 100 US Federal Contractors

References[edit]

- ^ a b «Certificate of Incorporation of Computing-Tabulating-Recording-Co», Appendix to Hearings Before the Committee on Patents, House of Representatives, Seventy-Fourth Congress, on H. R. 4523, Part III, United States Government Printing Office, 1935 [Incorporation paperwork filed June 16, 1911], archived from the original on August 3, 2020, retrieved July 18, 2019

- ^ a b «IBM Is Blowing Up Its Annual Performance Review». Fortune. February 1, 2016. Archived from the original on October 29, 2020. Retrieved July 22, 2016.

- ^ «IBM – Arvind Krishna – Chief Executive Officer». www.ibm.com. Archived from the original on March 8, 2022. Retrieved March 8, 2022.

- ^ «IBM Newsroom — Gary Cohn». IBM Newsroom. Retrieved March 8, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f «IBM Reports 2022 Fourth-Quarter and Full-Year Results» (PDF). IBM.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 24, 2022. Retrieved February 19, 2022.

- ^ «IBM100 — The Making of International Business Machines». www-03.ibm.com. March 7, 2012. Retrieved December 30, 2022.

- ^ «Trust and responsibility. Earned and practiced daily». IBM Impact. June 27, 2019. Retrieved December 30, 2022.

- ^ a b «10-K». 10-K. Archived from the original on December 5, 2019. Retrieved June 1, 2019.

- ^ a b Bajpai, Prableen (January 29, 2021). «Top Patent Holders of 2020». nasdaq.com. Nasdaq. Archived from the original on January 30, 2021. Retrieved February 2, 2021.

- ^ «2021 Top 50 US Patent Assignees». IFI CLAIMS Patent Services. January 5, 2022. Retrieved August 22, 2022.

- ^ Gil, Darío (January 6, 2023). «Why IBM is no longer interested in breaking patent records–and how it plans to measure innovation in the age of open source and quantum computing». Fortune. Archived from the original on January 27, 2023. Retrieved February 3, 2023.

- ^ a b «IBM | Founding, History, & Products | Britannica». www.britannica.com. Retrieved December 30, 2022.

- ^ «IBM Tops U.S. Patent List for 28th Consecutive Year with Innovations in Artificial Intelligence, Hybrid Cloud, Quantum Computing and Cyber-Security». IBM Newsroom. Retrieved July 14, 2023.

- ^ «About us». IBM Research. February 9, 2021. Retrieved December 30, 2022.

- ^ a b «Fortune 500». Fortune. Retrieved December 30, 2022.

- ^ Schofield, Jack (January 21, 2018). «IBM shows growth after 22 straight quarters of declining revenues, but has it turned the corner?». ZDNET. Ziff-Davis. Archived from the original on March 10, 2023.

- ^ «IBM Brand Ranking | All Brand Rankings where IBM is listed!». www.rankingthebrands.com. Retrieved December 30, 2022.

- ^ Aswad, Ed; Meredith, Suzanne (2005). IBM in Endicott. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing. p. 8. ISBN 0-7385-3700-4.

- ^ Aswad, Ed; Meredith, Suzanne (2005). Images of America: IBM in Endicott. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 0-7385-3700-4. Archived from the original on January 8, 2021. Retrieved October 22, 2020.

- ^ «Dey dial recorder, early 20th century». scienceandsociety.co.uk. UK Science Museum. Archived from the original on October 23, 2020. Retrieved December 30, 2010.

- ^ «Hollerith 1890 Census Tabulator». columbia.edu. Columbia University. Archived from the original on April 20, 2011. Retrieved December 30, 2010.

- ^ «Employee Punch Clocks». floridatimeclock.com. Florida Time Clock. Archived from the original on July 11, 2011. Retrieved December 30, 2010.

- ^ «Tabulating Concerns Unite: Flint & Co. Bring Four Together with $19,000,000 capital» (PDF). The New York Times. June 10, 1911. p. 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 25, 2021. Retrieved June 14, 2018.

- ^ Belden, Thomas Graham; Belden, Marva Robins (1962). The Lengthening Shadow: The Life of Thomas J. Watson. Little, Brown and Co. pp. 89–93.

- ^ Campbell-Kelly, Martin; Aspray, William F.; Yost, Jeffrey R.; Tinn, Honghong; Díaz, Gerardo Con (2023). Computer: A History of the Information Machine. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-000-87875-2.

- ^ Belden (1962) p. 105

- ^ a b c «Chronological History of IBM, 1910s». ibm.com. IBM. January 23, 2003. Archived from the original on August 26, 2018. Retrieved January 30, 2015.

- ^ Marcosson, Isaac F. (1945). Wherever Men Trade: The Romance of the Cash Register. New York (NY): Dodd, Mead & Co. ISBN 9780405047138. OCLC 243101.

- ^ Belden (1962) p. 125

- ^ (Rodgers, THINK, p. 83)

- ^ Black, Edwin (2008). IBM and the Holocaust: The Strategic Alliance Between Nazi Germany and America’s Most Powerful Corporation. Dialog Press. ISBN 9780914153108.

- ^ Pauwels, Jacques R. (2017). Big Business and Hitler (in German). James Lorimer & Company. ISBN 978-1-4594-0987-3.

- ^ Allen, Michael (January 1, 2002). ««Stranger than Science Fiction: Edwin Black, IBM, and the Holocaust.»«. Johns Hopkins University Press. 43 (1): 150–154. JSTOR 25147861. Retrieved March 7, 2022.

- ^ «The IBM Corporate Service Corps». ibm.org. IBM CSC. August 12, 2016. Archived from the original on November 24, 2019. Retrieved August 12, 2016.

- ^ a b Chong, Rachael; Fleming, Melissa (November 5, 2014). «Why IBM Gives Top Employees a Month to Do Service Abroad». Harvard Business Review. Archived from the original on November 26, 2020. Retrieved August 12, 2016.

- ^ «Extreme Blue web page». ibm.com. 01.ibm.com. September 7, 2007. Archived from the original on February 13, 2019. Retrieved May 23, 2010.

- ^ a b Taft, Derryl (April 25, 2016). «IBM Launches Distinguished Designer Program». eWeek. Retrieved August 12, 2016.

- ^ Campbell-Kelly, Martin (2003). From Airline Reservations to Sonic the Hedgehog: A History of the Software Industry. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. pp. 140–143, 175–176, 237.

- ^ Sullivan, Lawrence A. (April 1982). «Monopolization: Corporate Strategy, the IBM Cases, and the Transformation of the Law». Texas Law Review. 60 (4): 587–647. Archived from the original on January 14, 2022. Retrieved January 14, 2022.

- ^ «The history of the UPC bar code and how the bar code symbol and system became a world standard». cummingsdesign.com. Cummingsdesign. Archived from the original on November 9, 2020. Retrieved May 17, 2011.

- ^ Ross; Westerfield; Jordan (2010). Fundamentals of Corporate Finance (9th, alternate ed.). McGraw Hill. p. 746.

- ^ Miller, Michael W. (November 10, 1992). «‘Break Up IBM,’ Cry Some Investors Who See Value in Those Baby Blues». The Wall Street Journal. Dow Jones & Company: C1 – via ProQuest.

- ^ Ziegler, Bart (September 6, 1992). «Big Blue still breaking up its bureaucracy». Colorado Springs-Gazette: E3 – via ProQuest.

- ^ «Facts, Figures on IBM’s 13 Decentralized Firms». The Salt Lake Tribune. Associated Press: D14. September 6, 1992 – via ProQuest.

- ^ Lewis, Peter H. (December 22, 1991). «The Executive Computer; Can I.B.M. Learn From a Unit It Freed?». The New York Times.

- ^ Burgess, John (September 3, 1992). «IBM Plans Division For Its PC Business; One Executive Expected to Be Put in Control». The Washington Post. p. B11. Archived from the original on May 12, 2023.

- ^ Burgess, John (November 26, 1992). «With New Approach and Executive Team, IBM Seeks a Rebirth». The Washington Post. p. D1. Archived from the original on May 12, 2023.

- ^ Hooper, Lawrence (September 3, 1992). «IBM to Unveil New Structure of PC Business». The Wall Street Journal. Dow Jones & Company: A3 – via ProQuest.

- ^ «IBM reports record loss of $8 billion». Austin American-Statesman. Knight-Ridder Tribune Service. Associated Press: B6. July 28, 1993 – via ProQuest.

- ^ Lohr, Steve (August 2, 1993). «I.B.M. and Dell Stake Out the Little Picture in PC’s». The New York Times: D2. Archived from the original on May 26, 2015.

- ^ Burke, Steven (September 11, 1995). «IBM Power Personal Systems group to be folded into PC Co». Computer Reseller News. CMP Publications (648): 7 – via ProQuest.

- ^ Lefever, Guy; Pesanello, Michele; Fraser, Heather; Taurman, Lee (2011). «Life science: Fade or flourish ?» (PDF). IBM Institute for Business Value. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 23, 2014. Retrieved July 6, 2013.

- ^ «IBM Archives: Louis V. Gerstner, Jr». www.ibm.com. January 23, 2003. Archived from the original on September 20, 2020. Retrieved July 10, 2019.

- ^ Linda Rosencrance (July 30, 2002). «IBM to acquire PwC Consulting for $3.5 billion». Computerworld. Retrieved October 4, 2022.

- ^ Stephen Shankland (July 31, 2002). «IBM grabs consulting giant for $3.5 billion». Retrieved October 4, 2022.

- ^ Zimmerman, Michael R.; Lisa Dicarlo (December 14, 1998). «Not Your Father’s PC Company Anymore». PC Week. Ziff-Davis. 15 (50): 1 – via ProQuest.

- ^ Hansell, Saul (October 25, 1999). «The Strategy For I.B.M.: Loss-Leader PC Sales». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 29, 2023.

- ^ Greiner, Lynn (October 22, 1999). «Big Blue to combine PC division with PSG». Computing Canada. Plesman Publications. 25 (40): 6 – via ProQuest.

- ^ Won Choi, Hae (September 15, 2004). «IBM, LG Electronics Call Halt To PC Joint Venture in Korea». The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved November 25, 2022.

- ^ Sung-ha, Park (August 30, 2004). «LG, IBM to split by end of year». Korea JoongAng Daily. Retrieved November 25, 2022.

- ^ «IBM, LG Electronics to End Joint Venture». Forbes. Archived from the original on October 22, 2004.

- ^ Vance, Ashlee. «South Korea slams IBM with server slush fund charges». www.theregister.com. Retrieved November 25, 2022.

- ^ «Laptop Retrospective». Laptop Retrospective. Retrieved April 16, 2023.

- ^ «Lenovo Completes Acquisition Of IBM’s Personal Computing Division». 03.ibm.com. IBM. Archived from the original on November 10, 2020. Retrieved March 1, 2019.

- ^ «IBM Plans to Acquire Texas Memory Systems». IBM. Archived from the original on October 12, 2020. Retrieved August 17, 2012.

- ^ Saba, Jennifer (June 5, 2013). «IBM to buy website hosting service SoftLayer». Reuters. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved July 1, 2017.

- ^ Joseph, George (March 20, 2019). «Inside the Video Surveillance Program IBM Built for Philippine Strongman Rodrigo Duterte». The Intercept. Archived from the original on January 4, 2021. Retrieved January 17, 2020.

- ^ «Lenovo says $2.1 billion IBM x86 server deal to close on Wednesday» (Press release). Reuters. September 29, 2014. Archived from the original on November 17, 2015. Retrieved July 1, 2017.

- ^ «Apple + IBM». ibm.com. IBM. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved July 18, 2014.

- ^ Etherington, Darrell (July 15, 2014). «Apple Teams Up With IBM For Huge, Expansive Enterprise Push». marketbusinessnews.com. Tech Crunch. Archived from the original on December 15, 2020. Retrieved July 18, 2014.

- ^ Nordqvist, Christian (November 2, 2014). «Landmark IBM Twitter partnership to help businesses make decisions». Market Business News. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved November 2, 2014.

- ^ Ha, Anthony (May 6, 2015). «IBM Announces Marketing Partnership With Facebook». TechCrunch. Archived from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved August 13, 2016.

- ^ Kyung-Hoon, Kim (November 3, 2014). «Tencent teams up with IBM to offer business software over the cloud». Reuters. Archived from the original on October 23, 2020. Retrieved August 13, 2016.

- ^ Vanian, Jonathan. «Cisco and IBM’s New Partnership Is a Lot About Talk». Fortune. Archived from the original on October 27, 2020. Retrieved August 13, 2016.

- ^ Terdiman, Daniel (January 6, 2016). «IBM, Under Armour Team Up To Bring Cognitive Computing To Fitness Apps». Fast Company. Archived from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved August 13, 2016.

- ^ Franklin, Curtis Jr. (June 26, 2015). «IBM, Box Cloud Partnership: What It Means». Information Week. Archived from the original on November 21, 2020. Retrieved August 13, 2016.

- ^ Weinberger, Matt. «Microsoft just made a deal with IBM – and Apple should be nervous». Business Insider. Archived from the original on August 9, 2020. Retrieved August 13, 2016.

- ^ Forrest, Conner (June 14, 2016). «VMware and SugarCRM expand partnerships with IBM, make services available on IBM Cloud». Tech Republic. Archived from the original on August 23, 2020. Retrieved August 13, 2016.

- ^ Taft, Darryl (July 25, 2016). «IBM, CSC Expand Their Cloud Deal to the Mainframe». eWeek. Retrieved August 13, 2016.

- ^ Taft, Darryl (July 22, 2016). «Macy’s Taps IBM, Satisfi for In-Store Shopping Companion». eWeek. Retrieved August 13, 2016.

- ^ Toppo, Greg. «Sesame Workshop, IBM partner to use Watson for preschoolers». USA Today. Archived from the original on October 15, 2020. Retrieved August 13, 2016.

- ^ Nusca, Andrea. «IBM, Salesforce Strike Global Partnership on Cloud, AI». Fortune. Archived from the original on November 11, 2020. Retrieved March 7, 2017.

- ^ «IBM Buys Merge Healthcare to Boost Watson Health Cloud». Bloomberg. August 6, 2015. Archived from the original on September 25, 2020. Retrieved March 7, 2017.

- ^ «IBM Agrees to Acquire Weather Channel’s Digital Assets». Bloomberg. Archived from the original on October 13, 2020. Retrieved October 28, 2015.

- ^ Hardy, Quentin (October 28, 2015). «IBM to Acquire the Weather Company». The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 14, 2020. Retrieved October 28, 2015.

- ^ «IBM acquires Ustream, launches cloud video unit». USA Today. January 21, 2016. Archived from the original on October 15, 2020. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- ^ McLain, Tilly (January 21, 2016). «IBM Acquires Ustream: Behind the Acquisition». Ustream Online Video Blog. Archived from the original on January 22, 2016. Retrieved August 22, 2016.

- ^ Egan, Matt (April 19, 2016). «Big Blue isn’t so big anymore». CNN Money. Archived from the original on October 31, 2020. Retrieved April 22, 2016.

- ^ Stempel, Jonathan (May 9, 2016). «Groupon sues ‘once-great’ IBM over patent». Reuters. Archived from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved May 9, 2016.

- ^ Goldman, David (October 28, 2015). «IBM Buys Digital Part of The Weather Company». CNN Money. Archived from the original on December 30, 2020. Retrieved November 27, 2019.

- ^ Greene, Jay; McMillan, Robert (October 28, 2018). «IBM to Acquire Red Hat for About $33 Billion». The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on November 9, 2020. Retrieved October 29, 2018.

- ^ Hammond, Ed; Porter, Kiel; Barinka, Alex (October 28, 2018). «IBM Nears Deal to Acquire Software Maker Red Hat». Bloomberg.com. Archived from the original on September 2, 2020. Retrieved October 28, 2018.

- ^ «IBM to Acquire Red Hat». Archived from the original on October 28, 2018. Retrieved October 28, 2018.

- ^ «IBM Closes Landmark Acquisition of Red Hat for $34 Billion; Defines Open, Hybrid Cloud Future». www.redhat.com. July 9, 2019. Archived from the original on December 16, 2020. Retrieved July 9, 2019.

- ^ «IBM To Accelerate Hybrid Cloud Growth Strategy And Execute Spin-Off Of Market-Leading Managed Infrastructure Services Unit». ibm.com. IBM Corporation. Archived from the original on January 7, 2021. Retrieved October 10, 2020.

- ^ Vengattil, Munsif (October 9, 2020). «IBM to break up 109-year old company to focus on cloud growth». www.reuters.com. Reuters. Archived from the original on October 15, 2020. Retrieved October 10, 2020.

- ^ Goodwin, Jazmin (October 8, 2020). «IBM spins off a quarter of the company to focus on the cloud». cnn.com. CNN. Archived from the original on November 26, 2020. Retrieved October 10, 2020.

- ^ Bursztynsky, Jessica (October 8, 2020). «IBM shares rise on plans to spin off its IT infrastructure unit and focus on the cloud business». cnbc.com. CNBC. Archived from the original on November 11, 2020. Retrieved October 10, 2020.

- ^ Asa Fitch and Dave Sebastian (October 8, 2020). «IBM to Spin Off Services Unit to Accelerate Cloud-Computing Pivot». Wall Street Journal. The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved October 10, 2020.

- ^ Bendor-Samuel, Peter. «IBM Splits Into Two Companies». Forbes. Archived from the original on November 29, 2020. Retrieved October 10, 2020.

- ^ Moorhead, Patrick. «IBM Spinning Off Infrastructure Managed Services Group To Focus On Cloud Is A Good Move». Forbes. Archived from the original on November 9, 2020. Retrieved October 10, 2020.

- ^ Deutscher, Maria (January 7, 2021). «IBM names Martin Schroeter as CEO of $19B NewCo services spinoff». SiliconANGLE. Archived from the original on January 11, 2021. Retrieved February 23, 2021.

- ^ «IBM names former financial chief Martin Schroeter as head of new IT infrastructure services company». ETCIO. Reuters. January 8, 2021. Archived from the original on June 14, 2021. Retrieved February 23, 2021.

- ^ Arvind Krishna (March 7, 2022). «Update on Our Actions: War in Ukraine». IBM. Retrieved March 7, 2022.

- ^ «IBM finally shutters Russian operations, lays off staff». The Register. June 7, 2022.

- ^ «Contact Us». IBM. Archived from the original on December 30, 2020. Retrieved October 20, 2009.

- ^ Salmans, Sandra (January 9, 1982). «Dominance Ended, I.B.M. Fights Back». The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 27, 2020. Retrieved January 2, 2015.

- ^ Zuckerman, Laurence (September 17, 1997). «IBM’s New Headquarters Reflects A Change in Corporate Style». The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved August 22, 2016.

- ^ «On the Dedication of the Louis V. Gerstner, Jr., Center for Learning – THINK Blog». IBM. October 2, 2018. Archived from the original on August 31, 2020. Retrieved October 2, 2018.

- ^ «Property Overview». Dolce Hotels and Resorts. Archived from the original on September 17, 2016. Retrieved August 12, 2016.

- ^ «Company Overview of IBM China Company Limited». Bloomberg. Archived from the original on June 26, 2020. Retrieved September 19, 2018.

- ^ «Watson IoT Headquarters». IBM. May 17, 2017. Archived from the original on October 12, 2020. Retrieved October 6, 2018.

- ^ Forgey, Benjamin (March 24, 1990). «In the IBM Honoring the Corporation’s Buildings». The Washington Post.

- ^ «Environmental Protection». IBM. May 3, 2008. Archived from the original on September 3, 2007. Retrieved May 17, 2008.

- ^ «Village of Endicott Environmental Investigations». Archived from the original on October 25, 2020. Retrieved January 28, 2015.

- ^ Chittum, Samme (March 15, 2004). «In an I.B.M. Village, Pollution Fears Taint Relations With Neighbors». New York Times Online. Archived from the original on August 8, 2020. Retrieved May 1, 2008.

- ^ Owens, Jeremy C. «IBM earnings and revenue continue to shrink, stock falls 6%». MarketWatch. Archived from the original on April 28, 2021. Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- ^ «IBM Market Cap 2006–2021 | IBM». www.macrotrends.net. Archived from the original on April 29, 2021. Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- ^ «Fortune 500». Fortune. Archived from the original on December 31, 2020. Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- ^ Sorkin, Andrew Ross (October 20, 2014). «The Truth About IBM’s Buybacks». DealBook. Archived from the original on April 10, 2021. Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- ^ Saft, James (October 21, 2014). «IBM and the financial engineering economy: James Saft». Reuters. Archived from the original on April 29, 2021. Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- ^ «Boring IBM Just Got a Lot More Interesting». Bloomberg.com. October 8, 2020. Archived from the original on April 29, 2021. Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- ^ «IBM Investing $3B in Internet of Things». PCMAG. Archived from the original on August 9, 2020. Retrieved May 28, 2015.

- ^ «Digital workplace services | IBM». Digital workplace services | IBM. Archived from the original on December 19, 2020. Retrieved March 27, 2020.

- ^ «IBM Products». IBM. Archived from the original on June 13, 2017. Retrieved August 13, 2016.

- ^ «Data Center Knowledge – SoftLayer: $78 Million in First Quarter Revenue». May 17, 2011. Archived from the original on October 25, 2020. Retrieved August 14, 2016.

- ^ «Cloud computing news: Security». ibm.com. October 21, 2015. Archived from the original on December 29, 2017. Retrieved September 23, 2016.

- ^ Lunden, Ingrid (February 22, 2016). «IBM Inks VMware, GitHub, Bitly Deals, Expands Apple Swift Use As It Doubles Down On The Cloud». TechCrunch. Archived from the original on November 27, 2020. Retrieved August 14, 2016.

- ^ «IBM delivers Power-based chip for Microsoft Xbox 360 worldwide launch». IBM. October 25, 2005. Archived from the original on December 17, 2006. Retrieved March 22, 2007.

- ^ Staff Writer (June 8, 2011). «IBM microprocessors drive the new Nintendo WiiU console». mybroadband.co.za. Archived from the original on September 26, 2020. Retrieved June 17, 2011.

- ^ Leung, Isaac (June 8, 2011). «IBM’s 45nm SOI microprocessors at core of Nintendo Wii U». Electronics News. Archived from the original on July 14, 2011. Retrieved June 17, 2011.

- ^ «Building a smarter planet». Asmarterplanet.com. Archived from the original on October 15, 2018. Retrieved May 23, 2010.

- ^ «New research initiative sees IBM commit $3 bn». San Francisco News.Net. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved July 10, 2014.

- ^ Dignan, Larry (August 23, 2016). «IBM launches flash arrays for smaller enterprises, aims to court EMC, Dell customers». ZDNet. Archived from the original on October 21, 2020. Retrieved August 23, 2016.

- ^ «IBM. Global locations for your global business». IBM. Archived from the original on November 11, 2020. Retrieved December 9, 2019.

- ^ «Kenexa Corporation | Company Profile from Hoover’s». Hoovers.com. Archived from the original on June 15, 2012. Retrieved October 8, 2015.

- ^ Hardy, Quentin (October 28, 2015). «IBM to Acquire the Weather Company». The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 14, 2020. Retrieved September 19, 2018.

- ^ Lohr, Steve (January 12, 2010). «Big Blue’s Smarter Marketing Playbook». The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 16, 2010. Retrieved August 8, 2010.

- ^ Terdiman, Daniel (August 2, 2010). «At IBM Research, a constant quest for the bleeding edge». CNET News. Retrieved August 8, 2010.[dead link]

- ^ «Smart Grid». IBM. Archived from the original on April 9, 2011.

- ^ «Smarter Water Management». IBM. Archived from the original on April 18, 2010.

- ^ «Smart traffic». IBM. Archived from the original on May 4, 2010.

- ^ «Smarter Buildings». IBM. Archived from the original on June 14, 2011.

- ^ «About developerWorks». IBM developerWorks. Archived from the original on May 19, 2018. Retrieved August 22, 2016.

- ^ «What is Watson?». IBM. Archived from the original on October 30, 2016. Retrieved August 13, 2016.

- ^ «Watson Oncology». Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. Archived from the original on October 13, 2016. Retrieved August 13, 2016.

- ^ Upbin, Bruce. «IBM’s Watson Now A Customer Service Agent, Coming To Smartphones Soon». Forbes. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved August 13, 2016.

- ^ «IBM Unveils Q System One Quantum Computer». ExtremeTech. January 10, 2019. Archived from the original on December 24, 2020. Retrieved February 25, 2019.

- ^ «NYPD changes the crime control equation by transforming the way it uses information» (PDF). Road Armonk, NY: IBM Corporation. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 8, 2021. Retrieved June 8, 2019.

- ^ Miller, Joe (March 13, 2020). «IBM to build Europe’s first quantum computer in Germany». Financial Times. Archived from the original on November 19, 2020. Retrieved July 20, 2021.

- ^ «IBM Policy». IBM.

- ^ «IBM exits facial recognition business, calls for police reform». Reuters. June 9, 2020.

- ^ «IBM steps up its cloud partnership strategy with AWS deal». Tech Target. May 13, 2022. Retrieved May 18, 2022.

- ^ «How Quantum Computing Will Transform Our World». Time. Retrieved February 7, 2023.

- ^ «IBM to Spin off $19B Business to Focus on Cloud Computing». Associated Press. October 8, 2020. Retrieved October 13, 2020.

- ^ «IBM to name infrastructure services business ‘Kyndryl’ after spinoff». Reuters. April 12, 2021. Archived from the original on July 25, 2021. Retrieved July 25, 2021 – via www.reuters.com.

- ^ «IBM to Acquire Software Provider Turbonomic for Over $1.5 Billion». NDTV Gadgets 360. April 30, 2021. Archived from the original on May 1, 2021. Retrieved May 1, 2021.

- ^ Condon, Stephanie (January 21, 2022). «IBM sells Watson Health assets to investment firm Francisco Partners». ZDNet. Archived from the original on January 21, 2022. Retrieved January 21, 2022.

- ^ «IBM and Rapidus Form Strategic Partnership to Build Advanced Semiconductor Technology and Ecosystem in Japan». IBM Newsroom. December 12, 2023.

- ^ «GlobalFoundries sues IBM, says trade secrets were unlawfully given to Japan’s Rapidus». CNBC. April 20, 2023.

- ^ «IBM Research: Global labs». Archived from the original on December 16, 2020. Retrieved May 28, 2015.

- ^ «IBM’s expenditure on research and development from 2005 to 2015 (in billion U.S. dollars)». Statista. Archived from the original on November 11, 2020. Retrieved August 12, 2016.

- ^ Bort, Julie. «Ginni Rometty just set a big goal for IBM: spending $4 billion to bring in $40 billion». Business Insider. Archived from the original on August 9, 2020. Retrieved August 12, 2016.

- ^ «IBM launches biggest Linux lineup ever». IBM. March 2, 1999. Archived from the original on November 10, 1999.

- ^ Hamid, Farrah (May 24, 2006). «IBM invests in Brazil Linux Tech Center». LWN.net. Archived from the original on January 8, 2021. Retrieved July 21, 2016.

- ^ «Interview: The Eclipse code donation». IBM. November 1, 2001. Archived from the original on December 18, 2009.

- ^ «IBM Archives: «IBM» atoms». IBM. January 23, 2003. Archived from the original on November 11, 2020. Retrieved July 22, 2012.

- ^ «The Nobel Prize in Physics 1986 – Press Release». Nobel Media AB. October 15, 1986. Archived from the original on August 2, 2018. Retrieved January 1, 2014.

- ^ Steele, Guy L. (2011). «An interview with Frances E. Allen». Communications of the ACM. 54: 39. doi:10.1145/1866739.1866752.

- ^ a b Selinger, Evan, ed. (2006). Postphenomenology: A Critical Companion to Ihde. State University of New York Press. p. 228. ISBN 0-7914-6787-2. Archived from the original on January 9, 2021. Retrieved October 22, 2020.

- ^ Morgan, Conway Lloyd; Foges, Chris (2004). Logos, Letterheads & Business Cards: Design for Profit. Rotovision. p. 15. ISBN 2-88046-750-0.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Walters, E. Garrison (2001). The Essential Guide to Computing: The Story of Information Technology. Publisher: Prentice Hall PTR. p. 55. ISBN 0-13-019469-7.

big blue ibm.

- ^ «IBM Archives». IBM. January 23, 2003. Archived from the original on January 5, 2021. Retrieved November 24, 2009.

- ^ Clayton, Ward. «IBM and Masters Celebrate 20 Years». Masters. Archived from the original on August 8, 2020. Retrieved August 12, 2016.

- ^ Weinman, Sam. «IBM CEO Ginni Rometty is Augusta National’s third female member». Golf Digest. Archived from the original on January 9, 2021. Retrieved August 12, 2016.

- ^ Snyder, Benjamin. «Why IBM dominates the U.S. Open». Forbes. Archived from the original on October 25, 2020. Retrieved August 12, 2016.

- ^ DiCarlo, Lisa. «IBM, Olympics Part Ways After 40 Years». Forbes. Archived from the original on November 13, 2020. Retrieved August 12, 2016.

- ^ Jinks, Beth (June 5, 2012). «IBM Ends Its NFL Sponsorship Over Difference in Views». Bloomberg.com. Bloomberg L.P. Archived from the original on August 28, 2020. Retrieved August 12, 2016.

- ^ «Best Global Brands Ranking for 2012». Interbrand. Archived from the original on May 31, 2013. Retrieved June 6, 2013.

- ^ «IBM #1 in Green Rankingss for 2012». thedailybeast.com. Archived from the original on September 29, 2015. Retrieved October 22, 2012.

- ^ Santoli, Michael (June 23, 2012). «The World’s Most Respected Companies». Barron’s. Archived from the original on October 16, 2020. Retrieved June 23, 2012.

- ^ «Tech Consulting Firm Rankings 2012: Best Firms in Each Practice Area». Vault. Archived from the original on October 11, 2011. Retrieved December 29, 2011.

- ^ «The World’s Most Valuable Brands». Forbes. Archived from the original on October 6, 2012. Retrieved September 2, 2015.

- ^ Thomas, Patrick (December 12, 2020). «The Best-Managed Companies of 2020—and How They Got That Way». Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on February 21, 2021. Retrieved February 2, 2021.

- ^ Ina Fried (March 8, 2022). «Tech companies increase donations to Ukraine». AXIOS. Retrieved March 8, 2022.

- ^ «IBM’s ESG Datasheet for 2020Q4». IBM. June 30, 2021. Archived from the original on November 10, 2021. Alt URL Archived November 10, 2021, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ «IBM Commits To Net Zero Greenhouse Gas Emissions By 2030». IBM Newsroom. IBM. February 16, 2021. Retrieved July 22, 2022.

IBM today announced that it will achieve net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 to further its decades-long work to address the global climate crisis. The company will accomplish this goal by prioritizing actual reductions in its emissions, energy efficiency efforts and increased clean energy use across the more than 175 countries where it operates.

- ^ «International Business Machines Corp. (IBM) profile». HRC Corporate Equality Index Score.[permanent dead link]

- ^ «IBM». Working Mother. Archived from the original on October 16, 2020. Retrieved April 28, 2018.

- ^ «The IBM Corporate Service Corps». IBM CSC. Archived from the original on November 24, 2019. Retrieved August 12, 2016.

- ^ «Extreme Blue web page». 01.ibm.com. September 7, 2007. Archived from the original on February 13, 2019. Retrieved May 23, 2010.

- ^ Smith, Paul Russell (1999). Strategic Marketing Communications: New Ways to Build and Integrate Communications. Kogan Page. p. 24. ISBN 0-7494-2918-6. Archived from the original on January 9, 2021. Retrieved October 22, 2020.

- ^ «IBM Attire». IBM Archives. IBM Corp. January 23, 2003. Archived from the original on August 14, 2018. Retrieved May 31, 2012.

- ^ Goldman, David. «IBM stands for ‘I’ve Been Moved’«. CNN Money. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved August 12, 2016.

- ^ «IBM stands for «I’m by myself’ for teleworkers of the blue giant». African America. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved August 12, 2016.

- ^ Intelligent Mentoring. IBM Press. November 11, 2008. ISBN 9780137009497. Archived from the original on January 9, 2021. Retrieved August 12, 2016.

- ^ Logan, John (December 2006). «The Union Avoidance Industry in the United States» (PDF). British Journal of Industrial Relations. 44 (4): 651–675. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8543.2006.00518.x. S2CID 155066215. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 17, 2016. Retrieved December 17, 2010.

- ^ «IBM Global Unions Links». EndicottAlliance.org. Archived from the original on October 14, 2013. Retrieved October 12, 2013.

- ^ Bort, Julie. «In Japan, IBM employees have formed a football team complete with pro stadium, cheerleaders and televised games». Business Insider. Archived from the original on January 9, 2021. Retrieved August 12, 2016.

- ^ «Switch to Macs from PCs reportedly saves IBM $270 per user». CIO. November 5, 2015. Archived from the original on August 20, 2018. Retrieved August 12, 2016.

- ^ Lebowitz, Shana (May 20, 2016). «After overhauling its performance review system, IBM now uses an app to give and receive real-time feedback». Business Insider. Archived from the original on October 12, 2020. Retrieved May 20, 2016.

- ^ «Timothy D. Cook Profile». Forbes. Archived from the original on May 18, 2012. Retrieved November 10, 2017.

- ^ «Executive Biographies – Lisa Su». Amd.com. Archived from the original on January 3, 2018. Retrieved October 10, 2014.

- ^ «Leadership Team». www.cadence.com. Archived from the original on December 25, 2021. Retrieved December 25, 2021.

- ^ Kearns, David T (May 31, 2005). «Crossing the Bridge: Family, Business, Education, Cancer, and the Lessons Learned». Meliora Press.

- ^ La Monica, Paul R. (February 8, 2008). «Fair Isaac CEO: FICO criticism isn’t ‘fair’«. CNN Money. Archived from the original on October 22, 2020. Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- ^ DeLaat, Jacqueline (2000). «Harris, Patricia Roberts». Women in World History, Vol. 7: Harr-I. Waterford, CT: Yorkin Publications. pp. 14–17. ISBN 0-7876-4066-2.

- ^ Miller, Zeke J. (November 19, 2013). «Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker: A 2016 Contender But Not A College Graduate». TIME. Archived from the original on December 9, 2020. Retrieved May 1, 2015.

- ^ «Official Manual of the State of Missouri, 1993–1994». p. 157.[permanent dead link]

- ^ «Katherine Harris’ Biography». Project Vote Smart. Archived from the original on January 24, 2012. Retrieved April 30, 2006.

- ^ «New York Times (May 31, 1998)». The New York Times. May 31, 1998. Archived from the original on October 10, 2013. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- ^ «Board of Directors — Officers». National Association of Sports Officials. Archived from the original on September 15, 2007. Retrieved September 27, 2007.

- ^ «Board of Directors». IBM. March 9, 2020. Archived from the original on July 8, 2020. Retrieved March 11, 2020.

- ^ McFarland, Matt. «Warren Buffett never liked tech stocks. So why does he own Apple?». The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved August 11, 2016.

- ^ Belvedere, Matthew J. (May 4, 2018). «Warren Buffett says Berkshire Hathaway has sold completely out of IBM». CNBC. Archived from the original on May 4, 2018. Retrieved May 4, 2018.

Further reading[edit]

- Bakis, Henry (1987). «Telecommunications and the Global Firm». In F. E. Ian Hamilton (ed.). Industrial change in advanced economies. London: Croom Helm. pp. 130–160. ISBN 9780709938286.