| Владимир Ильич Ульянов (Ленин) | |||

| Портрет Ленина работы Н. Андреева Портрет Ленина работы Н. Андреева |

|||

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Предшественник: |

должность учреждена |

||

| Преемник: |

Алексей Иванович Рыков |

||

|

|||

| Предшественник: |

должность учреждена; Александр Фёдорович Керенский как Министр-председатель Временного правительства |

||

| Преемник: |

Алексей Иванович Рыков |

||

|

|

|||

| Имя при рождении: |

Владимир Ильич Ульянов |

||

| Псевдонимы: |

В.Ильин, В.Фрей, Ив.Петров, К.Тулин, Карпов, Ленин, Старик. |

||

| Дата рождения: |

22 апреля 1870 |

||

| Место рождения: |

Симбирск, Российская империя |

||

| Дата смерти: |

21 января 1924 |

||

| Место смерти: |

Горки Ленинские, Московская губерния РСФСР, СССР |

||

| Гражданство: |

подданый Российской империи, гражданин РСФСР, гражданин СССР |

||

| Вероисповедание: |

Атеист |

||

| Образование: |

Казанский университет, Петербургский университет |

||

| Партия: |

РСДРП → РСДРП(б) → РКП(б) |

||

| Организация: |

Петербургский «Союз борьбы за освобождение рабочего класса» |

||

| Основные идеи: |

марксизм-ленинизм |

||

| Род деятельности: |

литератор, юрист, революционер |

||

| Классовая принадлежность: |

интеллигенция |

||

| Награды и премии: |

Орден Труда Хорезмской Народной Социалистической республики |

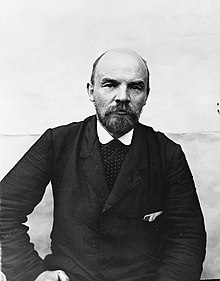

Влади́мир Ильи́ч Ле́нин (настоящая фамилия Улья́нов; 10 (22) апреля 1870 года, Симбирск — 21 января 1924 года, усадьба Горки, Московская губерния) — российский, советский политический и государственный деятель, выдающийся русский мыслитель, философ, основоположник марксизма-ленинизма, публицист, величайший пролетарский революционер, создатель партии большевиков, организатор и вождь Великой Октябрьской социалистической революции, основатель Советского государства, Председатель Совета Народных Комиссаров РСФСР и СССР, создатель III (Коммунистического) Интернационала.

Один из самых известных политических деятелей XX века, имя которого знает весь мир.

Биография[]

Детство, образование и воспитание[]

-

Основная статья: Семья Ульяновых

Владимир Ильич Ульянов родился в Симбирске (ныне Ульяновск) в 1870 году.

Дед Ленина — Н. В. Ульянов, крепостной крестьянин из Нижегородской губернии, впоследствии жил в г. Астрахани, был портным-ремесленником. Отец — И. Н. Ульянов, по окончании Казанского университета преподавал в средних учебных заведениях Пензы и Нижнего Новгорода, а затем был инспектором и директором народных училищ Симбирской губернии. И. Н. Ульянов дослужился до чина действительного статского советника и получил потомственное дворянство. Мать Ленина — М. А. Ульянова (урождённая Бланк, 1835—1916), дочь врача, получив домашнее образование, сдала экстерном экзамены на звание учительницы; всецело посвятила себя воспитанию детей.

Сестры — А. И. Ульянова-Елизарова, М. И. Ульянова и младший брат — Д. И. Ульянов впоследствии стали видными деятелями Коммунистической партии.

В 1879—1887 годах Владимир Ульянов учился в Симбирской гимназии, руководимой Ф. М. Керенским, отцом А. Ф. Керенского, будущего главы Временного правительства. В нём рано пробудился дух протеста против царского строя, социального и национального угнетения. Передовая русская литература, сочинения В. Г. Белинского, А. И. Герцена, Н. А. Добролюбова, Д. И. Писарева и особенно Н. Г. Чернышевского способствовали формированию его революционных взглядов. От старшего брата Александра Ленин узнал о марксистской литературе. В 1887 году окончил гимназию с золотой медалью и поступил на юридический факультет Казанского университета. Ф. М. Керенский был очень разочарован выбором Володи Ульянова, так как советовал ему поступать на историко-словесный факультет университета ввиду больших успехов младшего Ульянова в латыни и словесности.

В том же 1887 году 8 (20) мая, старшего брата Владимира Ильича — Александра казнили как участника народовольческого заговора с целью покушения на жизнь императора Александра III. Через три месяца после поступления Владимир Ильич был исключён за участие в студенческих беспорядках, вызванных новым уставом университета, введением полицейского надзора за студентами и кампанией по борьбе с «неблагонадёжными» студентами. По словам инспектора студентов, пострадавшего от студенческих волнений, Владимир Ильич находился в первых рядах бушевавших студентов, чуть ли не со сжатыми кулаками. В результате волнений Владимир Ильич в числе 40 других студентов оказался следующей ночью арестованным и отправленным в полицейский участок. Всех арестованных исключили из университета и выслали на «место родины». Позднее ещё одна группа студентов покинула Казанский университет в знак протеста против репрессий. В числе добровольно ушедших из университета был двоюродный брат Ленина, Владимир Александрович Ардашев. После ходатайств Любови Александровны Ардашевой, тёти Владимира Ильича, он был выслан в деревню Кокушкино Казанской губернии, где жил в доме Ардашевых до зимы 1888—1889 года. С этого времени Ленин посвятил всю свою жизнь делу борьбы против самодержавия и капитализма, делу освобождения трудящихся от гнёта и эксплуатации.

Начало революционной деятельности[]

В октябре 1888 Ленин вернулся в Казань. Здесь он вступил в один из марксистских кружков, организованных Н. Е. Федосеевым, в котором изучались и обсуждались сочинения К. Маркса, Ф. Энгельса, Г. В. Плеханова. В 1924 году Н. К. Крупская писала в «Правде»:

Шаблон:Начало цитатыПлеханова Владимир Ильич любил страстно. Плеханов сыграл крупную роль в развитии Владимира Ильича, помог ему найти правильный революционный путь, и потому Плеханов был долгое время окружен для него ореолом: всякое самое незначительное расхождение с Плехановым он переживал крайне болезненно.Шаблон:Конец цитаты

Труды Маркса и Энгельса сыграли решающую роль в формировании мировоззрения Ленина — он становится убеждённым марксистом.

Некоторое время Ленин пытался заниматься сельским хозяйством в купленном его матерью имении в Алакаевке (83,5 десятины) в Самарской губернии. При Советской власти в этом селе был создан дом-музей Ленина. Осенью 1889 года семья Ульяновых переезжает в Самару.

В 1891 году Владимир Ульянов сдал экстерном экзамены за курс юридического факультета Санкт-Петербургского университета.

В 1892-1893 гг. Владимир Ульянов работал помощником самарского присяжного поверенного (адвоката) Н. А. Хардина, ведя в большинстве уголовные дела, проводил «казенные защиты». Здесь в Самаре он организовал кружок марксистов, установил связи с революционной молодёжью других городов Поволжья, выступал с рефератами, направленными против народничества. К самарскому периоду относится первая из сохранившихся работ Ленина — статья «Новые хозяйственные движения в крестьянской жизни».

В конце августа 1893 года Ленин переехал в Петербург, где вступил в марксистский кружок, членами которого были С. И. Радченко, П. К. Запорожец, Г. М. Кржижановский и др. Легальным прикрытием революционной деятельности Ленина была работа помощником присяжного поверенного. Непоколебимая вера в победу рабочего класса, обширные знания, глубокое понимание марксизма и умение применить его к разрешению жизненных вопросов, волновавших народные массы, снискали уважение петербургских марксистов и сделали Ленина их признанным руководителем. Он устанавливает связи с передовыми рабочими (И. В. Бабушкиным, В. А. Шелгуновым и др.), руководит рабочими кружками, разъясняет необходимость перехода от кружковой пропаганды марксизма к революционной агитации в широких пролетарских массах.

Ленин первым из российских марксистов поставил задачу создания партии рабочего класса в России как неотложную практическую задачу и возглавил борьбу революционных социал-демократов за её осуществление. Он считал, что это должна быть пролетарская партия нового типа, по своим принципам, формам и методам деятельности отвечающая требованиям новой эпохи — эпохи империализма и социалистической революции.

Восприняв центральную идею марксизма об исторической миссии рабочего класса — могильщика капитализма и созидателя коммунистического общества, Ленин отдаёт все силы своего творческого гения, всеобъемлющую эрудицию, колоссальную энергию, редкостную работоспособность беззаветному служению делу пролетариата, становится профессиональным революционером, формируется как вождь рабочего класса.

В 1894 году Ленин написал труд «Что такое „друзья народа“ и как они воюют против социал-демократов?», в конце 1894 — начале 1895 гг. — работу «Экономическое содержание народничества и критика его в книге г. Струве (Отражение марксизма в буржуазной литературе)». Уже эти его первые крупные произведения отличались творческим подходом к теории и практике рабочего движения. В них Ленин подверг уничтожающей критике субъективизм народников и объективизм «легальных марксистов», показал последовательно марксистский подход к анализу российской действительности, охарактеризовал задачи пролетариата России, развил идею союза рабочего класса с крестьянством, обосновал необходимость создания в России подлинно революционной партии.

В апреле 1895 года Ленин выехал за границу для установления связи с группой «Освобождение труда». В Швейцарии познакомился с Плехановым, в Германии — с В. Либкнехтом, во Франции — с П. Лафаргом и др. деятелями международного рабочего движения. В сентябре 1895, возвратившись из-за границы, Ленин побывал в Вильнюсе, Москве и Орехово-Зуеве, где установил связи с местными социал-демократами. Осенью 1895 по его инициативе марксистские кружки Петербурга объединились в единую организацию — Петербургский «Союз борьбы за освобождение рабочего класса», который явился зачатком революционной пролетарской партии, впервые в России стал осуществлять соединение научного социализма с массовым рабочим движением.

«Союз борьбы» вёл активную пропагандистскую деятельность среди рабочих, им было выпущено более 70 листовок. В ночь с 8 (20) на 9 (21) декабря 1895 года Ленин вместе с его соратниками по «Союзу борьбы» был арестован и заключён в тюрьму, откуда продолжал руководить «Союзом». В тюрьме он пишет «Проект и объяснение программы социал-демократической партии», ряд статей и листовок, подготавливает материалы к своей книге «Развитие капитализма в России». В феврале 1897 года был выслан на 3 года в село Шушенское Минусинского округа Енисейской губернии. За активную революционную работу к ссылке была приговорена и Н. К. Крупская. Как невеста Ленина она также была направлена в Шушенское, где стала его женой. Здесь Ленин установил и поддерживал связь с социал-демократами Петербурга, Москвы, Нижнего Новгорода, Воронежа и других городов, с группой «Освобождение труда», вёл переписку с социал-демократами, находившимися в ссылке на Севере и в Сибири, сплотил вокруг себя ссыльных социал-демократов Минусинского округа. В ссылке Ленин написал свыше 30 работ, в том числе книгу «Развитие капитализма в России» и брошюру «Задачи русских социал-демократов», которые имели огромное значение для выработки программы, стратегии и тактики партии.

К концу 90-х годов под псевдонимом «К. Тулин» В. И. Ульянов приобретает известность в марксистских кругах. В ссылке Ульянов также консультировал по юридическим вопросам местных крестьян, составлял за них юридические документы.

Первая эмиграция 1900—1905[]

В 1898 году в Минске состоялся I съезд РСДРП, провозгласивший образование социал-демократической партии в России и издавший «Манифест Российской социал-демократической рабочей партии». С основными положениями «Манифеста» Ленин солидаризировался. Однако партия фактически ещё не была создана. Происходивший без участия Ленина и других видных марксистов съезд не смог выработать программу и устав партии, преодолеть разобщённость социал-демократического движения. Кроме того, все члены избранного съездом ЦК и большинство делегатов были тут же арестованы; многие представленные на съезде организации были разгромлены полицией. Находившиеся в сибирской ссылке руководители «Союза борьбы» решили объединить разбросанные по стране многочисленные социал-демократические организации и марксистские кружки с помощью общерусской нелегальной политической газеты. Борясь за создание пролетарской партии нового типа, непримиримой к оппортунизму, Ленин выступил против ревизионистов в международной социал-демократии (Э. Бернштейн и другие) и их сторонников в России («экономисты»). В 1899 году он составил «Протест российских социал-демократов», направленный против «экономизма». «Протест» был обсужден и подписан 17 ссыльными марксистами.

После окончания ссылки Ленин 29 января (10 февраля) 1900 года выехал из Шушенского. Следуя к новому месту жительства, Ленин останавливался в Уфе, Москве и других городах, нелегально посетил Петербург, всюду устанавливая связи с социал-демократами. Поселившись в феврале 1900 года в Пскове, Ленин провёл большую работу по организации газеты, в ряде городов создал для неё опорные пункты. 29 июля 1900 года выехал за границу, где наладил издание газеты «Искра». Ленин был непосредственным руководителем газеты. В редколлегию газеты вошли три представителя эмигрантской группы «Освобождение труда» — Плеханов, П. Б. Аксельрод и В. И. Засулич и три представителя «Союза борьбы» — Ленин, Мартов и Потресов. В среднем тираж газеты составлял 8000 экземпляров, а некоторых номеров — до 10 000 экземпляров. Распространению газеты способствовало создание сети подпольных организаций на территории Российской империи. «Искра» сыграла исключительную роль в идейной и организационной подготовке революционной пролетарской партии, в размежевании с оппортунистами. Она стала центром объединения партийных сил, воспитания партийных кадров.

В 1900—1905 гг. Ленин жил в Мюнхене, Лондоне, Женеве. В декабре 1901 года впервые подписал одну из своих статей, напечатанных в «Искре», псевдонимом «Ленин».

В борьбе за создание партии нового типа выдающееся значение имела ленинская работа «Что делать? Наболевшие вопросы нашего движения». В ней Ленин подверг критике «экономизм», осветил главные проблемы строительства партии, её идеологии и политики. Важнейшие теоретические вопросы были изложены им в статьях «Аграрная программа русской социал-демократии» (1902 год), «Национальный вопрос в нашей программе» (1903 год).

Участие в работе II съезда РСДРП (1903 год)[]

Шаблон:Смотри также

Шаблон:КПСС

С 17 июля по 10 августа 1903 года в Лондоне проходил II съезд РСДРП. Ленин принимал активное участие в подготовке съезда не только своими статьями в «Искре» и «Заре»; ещё с лета 1901 года вместе с Плехановым он работал над проектом программы партии, подготовил проект устава, составил план работы и проекты почти всех резолюций предстоящего съезда партии. Программа состояла из двух частей — программы-минимум и программы-максимум; первая предполагала свержение царизма и установление демократической республики, уничтожение остатков крепостничества в деревне, в частности возвращение крестьянам земель, отрезанных у них помещиками при отмене крепостного права (так называемых «отрезков»), введение восьмичасового рабочего дня, признание права наций на самоопределение и установление равноправия наций; программа-максимум определяла конечную цель партии — построение социалистического общества и условия достижения этой цели — социалистическую революцию и диктатуру пролетариата.

На самом съезде Ленин был избран в бюро, работал в программной, организационной и мандатной комиссиях, председательствовал на ряде заседаний и выступал почти по всем вопросам повестки дня.

К участию в съезде были приглашены как организации, солидарные с «Искрой» (и называвшиеся «искровскими»), так и не разделявшие её позицию. В ходе обсуждения программы возникла полемика между сторонниками «Искры» с одной стороны и «экономистами» (для которых оказалось неприемлемым положение о диктатуре пролетариата) и Бундом (по национальному вопросу) — с другой; в результате 2 «экономиста», а позже и 5 бундовцев покинули съезд.

Но обсуждение устава партии, 1-го пункта, определявшего понятие члена партии, обнаружило разногласия и среди самих искровцев, разделившихся на «твёрдых» (сторонников Ленина) и «мягких» (сторонников Мартова). «В моем проекте, — писал Ленин после съезда, — это определение было таково: „Членом Российской социал-демократической рабочей партии считается всякий, признающий ее программу и поддерживающий партию как материальными средствами, так и личным участием в одной из партийных организаций“. Мартов же вместо подчеркнутых слов предлагал сказать: работой под контролем и руководством одной из партийных организаций… Мы доказывали, что необходимо сузить понятие члена партии для отделения работающих от болтающих, для устранения организационного хаоса, для устранения такого безобразия и такой нелепости, чтобы могли быть организации, состоящие из членов партии, но не являющиеся партийными организациями, и т. д. Мартов стоял за расширение партии и говорил о широком классовом движении, требующем широкой — расплывчатой организации и т. д… „Под контролем и руководством“, — говорил я, — означают на деле не больше и не меньше, как: без всякого контроля и без всякого руководства». Предложенная Мартовым формулировка 1-го пункта была поддержана 28 голосами против 22 при 1 воздержавшемся; но после ухода бундовцев и экономистов группа Ленина получила большинство при выборах в ЦК партии; это случайное, как показали дальнейшие события, обстоятельство навсегда разделило партию на «большевиков» и «меньшевиков».

Тем не менее, несмотря на это, на съезде фактически завершился процесс объединения революционных марксистских организаций и была образована партия рабочего класса России на идейно-политических и организационных принципах, разработанных Лениным. Была создана пролетарская партия нового типа, партия большевиков. «Большевизм существует, как течение политической мысли и как политическая партия, с 1903 года», — писал Ленин в 1920 году. После съезда он развернул борьбу против меньшевизма. В работе «Шаг вперёд, два шага назад» (1904) Ленин разоблачил антипартийную деятельность меньшевиков, обосновал организационные принципы пролетарской партии нового типа.

Первая русская революция (1905—1907)[]

Шаблон:Смотри также

Революция 1905—1907 годов застала Ленина за границей, в Швейцарии. В этот период Ленин направлял работу большевистской партии по руководству массами.

На III съезде РСДРП, проходившем в Лондоне в апреле 1905 года, Ленин подчёркивал, что главная задача происходящей революции — покончить с самодержавием и остатками крепостничества в России. Несмотря на буржуазный характер революции её главной движущей силой должен был стать рабочий класс, как наиболее заинтересованный в её победе, а его естественным союзником — крестьянство. Одобрив точку зрения Ленина, съезд определил тактику партии: организация стачек, демонстраций, подготовка вооружённого восстания.

На IV (1906), V (1907) съездах РСДРП, в книге «Две тактики социал-демократии в демократической революции» (1905) и многочисленных статьях Ленин разработал и обосновал стратегический план и тактику большевистской партии в революции, подверг критике оппортунистическую линию меньшевиков.

При первой же возможности, 8 ноября 1905 года, Ленин нелегально, под чужой фамилией, прибыл в Петербург и возглавил работу избранного съездом Центрального и Петербургского комитетов большевиков; большое внимание уделял руководству газетами «Новая жизнь», «Пролетарий», «Вперёд». Под руководством Ленина партия готовила вооружённое восстание.

Летом 1906 года из-за полицейских преследований Ленин переехал в Куоккала (Финляндия), в декабре 1907 года он вновь был вынужден эмигрировать в Швейцарию, а в конце 1908 года — во Францию (Париж).

Вторая эмиграция (1908 — апрель 1917)[]

Шаблон:Заготовка раздела

В первых числах января 1908 г. Ленин вернулся в Швейцарию. Поражение революции 1905—1907 гг. не заставило его сложить руки, он считал неизбежным повторение революционного подъёма. «Разбитые армии хорошо учатся», — писал Ленин.

В 1909 году опубликовал свой главный философский труд «Материализм и эмпириокритицизм».

В 1912 году он решительно порывает с меньшевиками, настаивавшими на легализации РСДРП.

5 мая 1912 года вышел первый номер легальной большевистской газеты «Правда». Её главным редактором фактически был Ленин. Он почти ежедневно писал в «Правду» статьи, посылал письма, в которых давал указания, советы, исправлял ошибки редакции. За 2 года в «Правде» было опубликовано около 270 ленинских статей и заметок. Также в эмиграции Ленин руководил деятельностью большевиков в IV Государственной Думе, являлся представителем РСДРП во II Интернационале, писал статьи по партийным и национальным вопросам, занимался изучением философии.

С конца 1912 года Ленин жил на территории Австро-Венгрии. Здесь, в галицийском местечке Поронин, его застала Первая мировая война. Австрийские жандармы арестовали Ленина, объявив его царским шпионом. Чтобы освободить его, потребовалась помощь депутата австрийского парламента социалиста В. Адлера. На вопрос габсбургского министра «Уверены ли вы, что Ульянов — враг царского правительства?» Адлер ответил: «О, да, более заклятый, чем ваше превосходительство». 6 августа 1914 года Ленин был освобождён из тюрьмы, а через 17 дней был уже в Швейцарии. Вскоре по приезду Ленин огласил на собрании группы большевиков-эмигрантов свои тезисы о войне. Он говорил, что начавшаяся война является империалистической, несправедливой с обеих сторон, чуждой интересам трудящихся.

Многие современные историки обвиняют Ленина в пораженческих настроениях, сам же он объяснял свою позицию так: Прочного и справедливого мира — без грабежа и насилия победителей над побеждёнными, мира, при котором не был бы угнетён ни один народ, добиться невозможно, пока у власти стоят капиталисты. Покончить с войной и заключить справедливый, демократический мир может только сам народ. А для этого трудящимся надо повернуть оружие против империалистических правительств, превратив империалистическую бойню в войну гражданскую, в революцию против правящих классов и взять власть в свои руки. Поэтому кто хочет прочного, демократического мира, должен быть за гражданскую войну против правительств и буржуазии. Ленин выдвинул лозунг революционного пораженчества, сущность которого заключалась в голосовании против военных кредитов правительству (в парламенте), создании и укреплении революционных организаций среди рабочих и солдат, борьбе с правительственной патриотической пропагандой, поддержке братания солдат на фронте. Вместе с тем Ленин считал свою позицию глубоко патриотичной: «Мы любим свой язык и свою родину, мы полны чувства национальной гордости, и именно поэтому мы особенно ненавидим своё рабское прошлое… и своё рабское настоящее».

На партийных конференциях в Циммервальде (1915) и Кинтале (1916) Ленин отстаивает свой тезис о необходимости преобразования империалистической войны в войну гражданскую и одновременно утверждает, что в России может победить социалистическая революция («Империализм как высшая стадия капитализма»). В целом, отношение большевиков к войне отражалось в простом лозунге: «Поражение своего правительства».

Возвращение в Россию[]

Шаблон:Заготовка раздела

Апрель — июль 1917 года. «Апрельские тезисы»[]

Шаблон:Заготовка раздела

Июль — октябрь 1917 года[]

Шаблон:Заготовка раздела

Великая Октябрьская социалистическая революция 1917 года[]

-

Основная статья: Великая Октябрьская социалистическая революция

Шаблон:Заготовка раздела

После революции и в период Гражданской войны (1917—1921 годы)[]

Шаблон:Заготовка раздела

Последние годы (1921—1924)[]

Шаблон:Заготовка раздела

Болезнь и смерть[]

Шаблон:Заготовка раздела

Основные идеи[]

-

Основная статья: Марксизм-ленинизм

Шаблон:Заготовка раздела

Анализ капитализма и империализма как его высшей стадии[]

Шаблон:Заготовка раздела

Отношение к империалистической войне и революционное пораженчество[]

Шаблон:Заготовка раздела

Возможность первоначальной победы революции в одной стране[]

Шаблон:Заготовка раздела

Коммунизм, социализм и диктатура пролетариата[]

Шаблон:Заготовка раздела

Судьба тела Ленина[]

Шаблон:Смотри также

Шаблон:Заготовка раздела

Ленин в культуре, искусстве и языке[]

Шаблон:Заготовка раздела

Награды Ленина[]

Официальная прижизненная награда[]

Единственной официальной государственной наградой, которой был награждён В. И. Ленин, был Орден Труда Хорезмской Народной Социалистической республики (1922 год).

Других государственных наград, как РСФСР и СССР, так и иностранных государств, у Ленина не было.

Звания и премии[]

В 1917 году Норвегия выступила с инициативой присуждения Нобелевской премии мира Владимиру Ленину, с формулировкой «За торжество идей мира», как ответный шаг на изданный в Советской России «Декрет о Мире», выводивший в сепаратном порядке Россию из Первой мировой войны. Нобелевский комитет данное предложение отклонил в связи с опозданием ходатайства к установленному сроку — 1 февраля 1918 года, однако вынес решение, заключающееся в том, что комитет не будет возражать против присуждения Нобелевской премии мира В. И. Ленину, если существующее российское правительство установит мир и спокойствие в стране (как известно, путь к установлению мира в России преградила Гражданская война, начавшаяся в 1918 году). Мысль Ленина о превращении войны империалистической в войну гражданскую была сформулирована в его работе «Социализм и война», написанной ещё в июле-августе 1915 года.

В 1919 году по приказу Реввоенсовета Республики В. И. Ленин был принят в почётные красноармейцы 1 отделения 1 взвода 1 роты 195 стрелкового Ейского полка.

Псевдонимы Ленина[]

Шаблон:Заготовка раздела

Труды Ленина[]

Шаблон:Заготовка раздела

См. также[]

- Список мест, названных в честь В.И.Ленина

- Музей-мемориал В.И. Ленина

- Орден Ленина

Литература[]

Шаблон:Заготовка раздела

Примечания[]

da:Vladimir Lenin

en:Vladimir Lenin

es:Vladimir Lenin

nl:Vladimir Lenin

https://ria.ru/20170414/1491767713.html

Биография Владимира Ульянова (Ленина)

Биография Владимира Ульянова (Ленина) — РИА Новости, 03.03.2020

Биография Владимира Ульянова (Ленина)

Советский государственный и политический деятель, теоретик марксизма, основатель Коммунистической партии и Советского социалистического государства в России… РИА Новости, 14.04.2017

2017-04-14T10:30

2017-04-14T10:30

2020-03-03T03:49

/html/head/meta[@name=’og:title’]/@content

/html/head/meta[@name=’og:description’]/@content

https://cdnn21.img.ria.ru/images/147870/22/1478702220_0:0:1742:980_1920x0_80_0_0_14ff7d913a53cb5196df4abbfc68367e.jpg

россия

РИА Новости

internet-group@rian.ru

7 495 645-6601

ФГУП МИА «Россия сегодня»

https://xn--c1acbl2abdlkab1og.xn--p1ai/awards/

2017

РИА Новости

internet-group@rian.ru

7 495 645-6601

ФГУП МИА «Россия сегодня»

https://xn--c1acbl2abdlkab1og.xn--p1ai/awards/

Новости

ru-RU

https://ria.ru/docs/about/copyright.html

https://xn--c1acbl2abdlkab1og.xn--p1ai/

РИА Новости

internet-group@rian.ru

7 495 645-6601

ФГУП МИА «Россия сегодня»

https://xn--c1acbl2abdlkab1og.xn--p1ai/awards/

https://cdnn21.img.ria.ru/images/147870/22/1478702220_0:0:1742:1308_1920x0_80_0_0_cb774298bf79e5f60b05e4d3fd3b02c2.jpg

РИА Новости

internet-group@rian.ru

7 495 645-6601

ФГУП МИА «Россия сегодня»

https://xn--c1acbl2abdlkab1og.xn--p1ai/awards/

РИА Новости

internet-group@rian.ru

7 495 645-6601

ФГУП МИА «Россия сегодня»

https://xn--c1acbl2abdlkab1og.xn--p1ai/awards/

картотека — великая русская революция, владимир ленин (владимир ульянов), россия

Картотека — Великая русская революция, Владимир Ленин (Владимир Ульянов), Россия

Биография Владимира Ульянова (Ленина)

Советский государственный и политический деятель, теоретик марксизма, основатель Коммунистической партии и Советского социалистического государства в России Владимир Ильич Ульянов (Ленин) родился 22 апреля (10 апреля по старому стилю) 1870 года в Симбирске (ныне Ульяновск) в семье инспектора народных училищ, ставшего потомственным дворянином.

Его старший брат Александр — революционер-народоволец, в мае 1887 года был казнен за подготовку покушения на царя.

В том же году Владимир Ульянов окончил Симбирскую гимназию с золотой медалью, был принят в Казанский университет, но через три месяца после поступления был исключен за участие в студенческих беспорядках. В 1891 году Ульянов экстерном окончил юридический факультет Петербургского университета, после чего работал в Самаре в должности помощника присяжного поверенного.

В августе 1893 года он переехал в Санкт-Петербург, где вступил в марксистский кружок студентов Технологического института. В апреле 1895 года Владимир Ульянов выехал за границу и познакомился с группой «Освобождение труда», созданной в Женеве русскими эмигрантами во главе с Георгием Плехановым. Осенью того же года по его инициативе и под его руководством марксистские кружки Петербурга объединились в единый «Союз борьбы за освобождение рабочего класса». В декабре 1895 года Ульянов был арестован полицией. Провел более года в тюрьме, затем выслан на три года в село Шушенское Минусинского уезда Красноярского края под гласный надзор полиции.

Участниками «Союза» в 1898 году в Минске был проведен первый съезд Российской социал-демократической рабочей партии (РСДРП).

Находясь в ссылке, Владимир Ульянов продолжал теоретическую и организационную революционную деятельность. В 1897 году издал работу «Развитие капитализма в России», где пытался оспорить взгляды народников на социально-экономические отношения в стране и доказать, что в России назревает буржуазная революция. Познакомился с работами ведущего теоретика немецкой социал-демократии Карла Каутского, у которого заимствовал идею организации русского марксистского движения в виде централизованной партии «нового типа».

После окончания срока ссылки в январе 1900 года выехал за границу (последующие пять лет жил в Мюнхене, Лондоне и Женеве). Там, вместе с Георгием Плехановым, его соратниками Верой Засулич и Павлом Аксельродом, а также своим другом Юлием Мартовым, Владимир Ульянов начал издавать социал-демократическую газету «Искра». С 1901 года он стал использовать псевдоним «Ленин» и с тех пор был известен в партии под этим именем.

В 1903 году на II съезде российских социал-демократов в результате раскола на меньшевиков и большевиков Ленин возглавил «большинство», создав затем большевистскую партию.

С 1905 года по 1907 год Ленин нелегально жил в Петербурге, осуществляя руководство левыми силами. С 1907 года по 1917 год находился в эмиграции, где отстаивал свои политические взгляды во II Интернационале.

В начале Первой мировой войны, находясь на территории Австро-Венгрии, Ленин был арестован по подозрению в шпионаже в пользу Российского правительства, но благодаря участию австрийских социал-демократов был освобожден. После освобождения уехал в Швейцарию, где выдвинул лозунг о превращении империалистической войны в войну гражданскую.

Весной 1917 года Ленин вернулся в Россию. 17 апреля (4 апреля по старому стилю) 1917 года, на следующий день после прибытия в Петроград, он выступил с так называемыми «Апрельскими тезисами», где изложил программу перехода от буржуазно-демократической революции к социалистической, а также начал подготовку вооруженного восстания и свержения Временного правительства.

С апреля 1917 года Ленин становится одним из главных организаторов и руководителей Октябрьского вооруженного восстания и установления власти Советов.

В начале октября 1917 года он нелегально переехал из Выборга в Петроград. 23 октября (10 октября по старому стилю) на заседании Центрального Комитета РСДРП(б) по его предложению была принята резолюция о вооруженном восстании. 6 ноября (24 октября по старому стилю) в письме к ЦК Ленин потребовал немедленного перехода в наступление, ареста Временного правительства и захвата власти. Для непосредственного руководства вооруженным восстанием вечером он нелегально прибыл в Смольный. На следующий день, 7 ноября (25 октября по старому стилю) 1917 года в Петрограде произошло восстание и захват государственной власти большевиками. На открывшемся вечером заседании второго Всероссийского съезда Советов было провозглашено советское правительство — Совет Народных Комиссаров (СНК), председателем которого стал Владимир Ленин. Съездом были приняты первые декреты, подготовленные Лениным: о прекращении войны и о передаче частной земли в пользование трудящихся.

По инициативе Ленина в 1918 году был заключен Брестский мир с Германией.

После переноса столицы из Петрограда в Москву с марта 1918 года Ленин жил и работал в Москве. Его личная квартира и рабочий кабинет размещались в Кремле, на третьем этаже бывшего здания Сената. Ленин избирался депутатом Моссовета.

Весной 1918 года правительство Ленина начало борьбу против оппозиции закрытием анархистских и социалистических рабочих организаций, в июле 1918 года Ленин руководил подавлением вооруженного выступления левых эсеров. Противостояние ужесточилось в период Гражданской войны, эсеры, левые эсеры и анархисты, в свою очередь, наносили удары по деятелям большевистского режима; 30 августа 1918 года было совершено покушение на Ленина.

Во время Гражданской войны Ленин стал инициатором и идеологом политики «военного коммунизма». Он одобрил создание Всероссийской чрезвычайной комиссии по борьбе с контрреволюцией и саботажем (ВЧК), широко и бесконтрольно применявшей методы насилия и репрессий.

С окончанием Гражданской войны и прекращением военной интервенции в 1922 году начался процесс восстановления народного хозяйства страны. С этой целью по настоянию Ленина был отменен «военный коммунизм», продовольственная разверстка была заменена продовольственным налогом. Ленин ввел так называемую новую экономическую политику (НЭП), разрешившую частную свободную торговлю. В то же время он настаивал на развитии предприятий государственного типа, на электрификации, на развитии кооперации.

В мае и декабре 1922 года Ленин перенес два инсульта, однако продолжал диктовать заметки и статьи, посвященные партийным и государственным делам. Третий инсульт, последовавший в марте 1923 года, сделал его практически недееспособным.

21 января 1924 года Владимир Ленин скончался в подмосковном поселке Горки. 23 января гроб с его телом был перевезен в Москву и установлен в Колонном зале Дома Союзов. Официальное прощание проходило в течение пяти дней.

27 января 1924 года гроб с забальзамированным телом Ленина был помещен в специально построенном на Красной площади Мавзолее по проекту архитектора Алексея Щусева.

В годы советской власти на различных зданиях, связанных с деятельностью Ленина, были установлены мемориальные доски, в городах установлены памятники вождю. Были учреждены: орден Ленина (1930), премия имени Ленина (1925), Ленинские премии за достижения в области науки, техники, литературы, искусства, архитектуры (1957). В 1924-1991 годах в Москве работал Центральный музей Ленина. Именем Ленина был назван ряд предприятий, учреждений и учебных заведений.

В 1923 году ЦК РКП(б) создал Институт В И. Ленина, а в 1932 году в результате его объединения с Институтом Маркса и Энгельса был образован единый Институт Маркса — Энгельса — Ленина при ЦК ВКП(б) (позднее он стал называться Институтом марксизма-ленинизма при ЦК КПСС). В Центральном партийном архиве этого института (ныне — Российский государственный архив социально-политической истории) хранится более 30 тысяч документов, автором которых является Владимир Ленин.

Ленин был женат на Надежде Крупской, которую знал еще по петербургскому революционному подполью. Они обвенчались 22 июля 1898 года во время ссылки Владимира Ульянова в село Шушенское.

Материал подготовлен на основе информации РИА Новости и открытых источников

Памятник представляет собой выполненное из бетона скульптурное изображение фигуры В. И. Ленина, которая установлена на бетонный постамент.

Климашкина ул., д. 20-22

Улица 1905 года

Памятник В. И. Ленину находится в южной части парка Декабрьского восстания (сквер 1905 года) со стороны Шмитовского проезда.

Сквер им. 1905 г.

Улица 1905 года

Анадырский пр-д, д. 8 (пл. ж/д станции Лосиноостровская)

Бабушкинская

3.3

ГАУК «Парк культуры и отдыха „Красная Пресня“»

Несмотря на то, что памятник сооружен достаточно давно, он сохранился в прекрасном состоянии.

Новолужнецкий пр-д (площадь перед центральным входом в «Олимпийский комплекс „Лужники“»)

3.1

Горки Ленинские (перенесен из: Ленинградский пр-т, д. 15, территория ОАО «Кондитерская фабрика „Большевик“»)

Домодедовская

3.3

Дмитровское ш., д. 110 территория НПО «ЛЭМЗ»)

Селигерская

3.3

Лиственничная аллея (территория РГАУ-МСХА им. К. А. Тимирязева)

Петровско-Разумовская

Руставели ул., вл. 7

БутырскаяТимирязевская

Мира пр-т, д. 177

Ростокино

Мира пр-т, вл. 119 (у главного входа ВВЦ)

Народный пр-т, д. 17, стр. 28 (территория ГАУК г. Москвы «Измайловский парк культуры и отдыха» , центральная часть)

Соколиная гора

Перовская ул., д. 44а, к. 2 (на территории ГОУ СОШ № 796)

Перово

Буракова ул., д. 8, стр. 10

АвиамоторнаяШоссе ЭнтузиастовЛефортовоСоколиная гора

территория ГАУК г. Москвы ПКиО «Сокольники» (фонтанная пл.)

Матросская Тишина ул., д. 15/17

Люблинская ул., д. 48 (на территории сквера)

ЛюблиноПечатникиВолжская

Курьяновский б-р, д. 26

Марьино

3.4

1-я Карачаровская ул., д. 8 (на территории ОАО «ДОК-3»)

Волгоградский проспект

3.1

Самый удивительный памятник В.И.Ленину

Пр. Комсомольской площади, д.3Б

3.8

Природно-исторический парк»Кузьминки-Люблино»

Волжская

На излете советской власти в Москве был поставлен один из последних памятников организатору и руководителю Октябрьской революции 1917 года, председателю Совета Народных Комиссаров РСФСР, СССР, основателю Советского государства В.И. Ленину.

3.9

Мягкость линий фигуры и спокойный образ выделяют этот памятник на фоне других, посвященных вождю.

3.3

Летом 2008 года этот памятник пострадал от урагана.

Пер. Огородная слобода, д. 6

ТургеневскаяЧистые пруды

3.3

Единственный в Москве «двойной» памятник с Лениным, представляющий собой одновременно парную скульптурную группу.

Ленинский проспект, д.82/2

Проспект ВернадскогоНовые ЧерёмушкиУниверситет

3.4

Комплекс библиотеки органично включает в себя принципы и приемы архитектуры разных эпох — это и римские форумы, и асимметричные планы конструктивистов, и сдержанный стилизованный декор.

ЦАО, Воздвиженка ул., дом 3/5, корпус А-Б/В/Г, строение 2

3.4

Открыть аудиогид

Любопытное в архитектурном отношении здание Театра им. К.С. Станиславского (улица Тверская, д. 23) – один из очень романтичных памятников московской старины, история которого согласно московским преданиям тянется издалека.

ЦАО, Тверская ул., дом 23, строение 1

ПушкинскаяТверскаяЧеховская

Уникальное здание, архитектора Алексея Щусева, сложной ступенчатой формы, органично вписанное в исторический ансамбль Кремля.

Традиционное наименование памятника – «Работный дом», т.е. заведение, сочетавшее функции исправительного и благотворительного учреждения. Оно давало неимущим средства к выживанию, но препятствовало бродяжничеству и нищенству. Систему работных домов стала развивать в России Екатерина II, и они просуществовали до революции 1917 года.

ЦАО, Товарищеский пер., дом 22

3.2

Открыть аудиогид

«… а на лестнице к платформе в красноватом крымском мраморе мы видим окаменелые улитки, ракушки — остатки жизни каких-то древних южных морей, покрывавших много десятков миллионов лет тому назад весь Крым и Кавказ».

ЦАО, ул. Воздвиженка, д.3/5, стр.4(часть)

3.4

Народный университет был вузом, подобных которому не существовало ни в России, ни за рубежом.

ЦАО, Миусская пл., дом 6, строение 7

3.3

Ле́нин Влади́мир Ильи́ч (настоящая фамилия Ульянов; среди псевдонимов – В. Фрей, Ив. Петров, К. Тулин, Карпов) [10(22).4.1870, Симбирск, ныне Ульяновск – 21.1.1924, посёлок Горки Подольского уезда Московской губернии, ныне рабочий посёлок Горки Ленинские Ленинского городского округа Московской области], российский революционный, советский государственный и партийный деятель, идеолог и лидер большевиков, один из главных создателей РКП(б) (в 1952–1991 Коммунистическая партия Советского Союза) и советского государства. Потомственный дворянин (с 1877/1878). Сын И. Н. Ульянова. Брат А. И. Ульянова.

Детство и юность

Под влиянием участвовавших в подготовке покушения на императора Александра III своих старших брата и сестры – Александра (казнён в мае 1887) и Анны (в замужестве Ульяновой-Елизаровой) – воспринял непримиримость ко «всякому либерализму», отрицание значения эволюционного развития общества и плодотворности реформ. Этому также способствовали труды авторов революционной и демократической направленности, чтением которых он увлёкся. Высоко оценил попытку «Народной воли» захватить власть посредством террора, назвал её «величественной». Особое влияние на мировоззрение Ленина оказал, в частности, роман Н. Г. Чернышевского «Что делать?» (по словам Ленина, дал ему «заряд на всю жизнь»). Ленин избрал революционную борьбу за преобразование общества на социалистических началах, отказавшись от других возможностей, которые открывало перед ним пореформенное общество (в антиправительственное движение включились также его младшие брат Дмитрий и сестра Мария).

В 1887 г. Ленин поступил на юридический факультет Казанского университета, в декабре того же года участвовал в студенческой сходке протеста против «циркуляра о кухаркиных детях» И. Д. Делянова, ненадолго арестован, исключён из университета и выслан под негласный надзор полиции в Кокушкино, получил отказ на прошение о восстановлении в университете или о разрешении выехать за границу для продолжения образования. В октябре 1888 г. вернулся в Казань. В 1890 г. благодаря хлопотам матери, М. А. Ульяновой, получил разрешение сдать экстерном экзамены за весь курс юридического факультета в Санкт-Петербургском университете, сдал их в 1891 г.

Фото: Fine Art Images / Heritage Images / Getty Images

Начало революционной деятельности

По собственному признанию Ленина, он завершил марксистское самоопределение в 1892–1893 гг. в Самаре, где работал помощником присяжного поверенного. В августе 1893 г. переехал в Санкт-Петербург, вошёл в марксистский кружок студентов Технологического института. Выдвинулся среди петербургских марксистов, включившись в полемику представителей «легального марксизма» с либеральными народниками (реформистское направление в народничестве 1880–1890-х гг.), которые видели в капитализме чуждое для России явление и были сторонниками преобразования общественно-политического строя на началах социализма посредством мирных реформ. Ленин назвал их мнимыми друзьями народа за отход от революционных традиций («Что такое «друзья народа» и как они воюют против социал-демократов?», 1894). За неприятие революционных идей марксизма и стремление реформировать буржуазное общество на демократической основе критиковал и «легальных марксистов», вместе с тем солидаризировался с ними в оценке капитализма как органичного для России явления. Доказывал, что в стране сложились капиталистические социально-экономические отношения, при которых буржуазия превратила самодержавное правительство в «своего лакея» (позднее признавал, что завышал степень состоявшейся к 1890-м гг. капиталистической трансформации российского общества). Поэтому не буржуазии, а рабочему классу Ленин отводил передовую роль в борьбе с самодержавием, формой такой борьбы в соответствии с классическим марксизмом признавал буржуазно-демократическую революцию. Осуществление общедемократических требований рассматривал лишь как «расчистку дороги», ведущей к победе рабочих над «главным врагом трудящихся» – капиталом.

В апреле 1895 г. в Швейцарии встретился с членами группы «Освобождение труда» (тогда считал их, прежде всего Г. В. Плеханова, своими учителями) и деятелями западноевропейской социал-демократии. В Санкт-Петербурге руководил группой «стариков», которая в конце 1895 г. объединилась с группой Ю. О. Мартова в общегородскую марксистскую организацию (впоследствии Петербургский «Союз борьбы за освобождение рабочего класса»).

В декабре того же года арестован, как и Мартов. В 1897 г. сослан в Сибирь, отбывал ссылку [окончилась 29 января (10 февраля) 1900] в селе Шушенское Минусинского уезда Енисейской губернии. Вступил в брак с приехавшей к нему Н. К. Крупской. В ссылке закончил работу над книгой «Развитие капитализма в России» (опубликована легально в 1899 в Санкт-Петербурге под псевдонимом Владимир Ильин; 2-е изд., переработанное, – 1908), утверждал, что капиталистический прогресс ведёт к росту классовой борьбы пролетариата с буржуазией. Разделял основные идеи составленного П. Б. Струве «Манифеста…» Российской социал-демократической рабочей партии (РСДРП) (издан в 1898). Последовательно отстаивал задачи революционной социал-демократии в борьбе с реформаторским, «оппортунистическим», по словам Ленина, направлением в российском и международном социал-демократическом движении (определение «оппортунистические» впоследствии закрепилось в советской политической риторике и историографии для обозначения социал-реформистских течений). Одну из главных опасностей для дела революции видел в отвлечении рабочих от политической борьбы в пользу борьбы за их экономические права.

Первая эмиграция (1900–1905)

В 1900 г. уехал за границу; один из организаторов издания газеты «Искра», вошёл в состав её редакции наряду с Г. В. Плехановым, П. Б. Аксельродом, В. И. Засулич, Ю. О. Мартовым и А. Н. Потресовым. Опубликовал в «Искре» свыше 50 своих статей (до 1903), в декабре 1901 г. впервые подписал одну из них псевдонимом Ленин. Участвовал в корректировке разрабатывавшегося Плехановым проекта программы РСДРП, которая состояла из программы-минимум (свержение самодержавия в буржуазно-демократической революции, установление демократической республики) и программы-максимум (завоевание пролетариатом политической власти для построения социалистического общества). По предложению Ленина в программу включено положение об установлении диктатуры пролетариата (вместо «власти рабочих») после победы социалистической революции (отсутствовало в программах западноевропейских социал-демократических партий). В книге «Что делать?» (1902) изложил своё видение российской рабочей партии. Считал, что она должна вносить в рабочее движение революционное сознание [«дайте нам организацию революционеров – и мы перевернём Россию» (Ленин В. И. Полное собрание сочинений (далее ПСС). Т. 6. Москва, 1963. С. 127)], поскольку, по мнению Ленина, рабочий класс без влияния партии ограничится борьбой за свои экономические права (тред-юнионизмом), но не поднимется на политическую борьбу против самодержавия, а затем вместе с пролетариями других стран – на «победоносную коммунистическую революцию». Предложил модель построения и функционирования партии на началах, по выражению Р. Люксембург, «ультрацентрализма» (в отличие от сложившихся в Западной Европе партий парламентского типа и вразрез с типом массовых легальных социалистических партий). По мнению Ленина, партия должна быть конспиративной организацией профессиональных революционеров и властным руководящим органом. Эти идеи он использовал при составлении проекта устава РСДРП.

На II съезде РСДРП (июль – август 1903, Брюссель, Лондон) в острых дискуссиях с «экономистами» Ленин отстоял революционные положения программы РСДРП. В спорах с Ю. О. Мартовым, который стремился к созданию массовой рабочей партии и считал достаточным для члена РСДРП работу под контролем и руководством одной из партийных организаций, Ленин настаивал на том, чтобы каждый член партии лично участвовал в деятельности одной из низовых организаций (первый параграф устава РСДРП). Ленин не был поддержан большинством делегатов съезда, проголосовавших за позицию Мартова в этом вопросе. На съезде Ленин избран членом редколлегии газеты «Искра» (вместе с Г. В. Плехановым, а также Мартовым, который отказался войти в состав редколлегии, настаивая на сохранении прежних 6 редакторов). От «Искры» Ленин вошёл в Совет партии (существовал до 1905) – высший партийный орган, призванный согласовывать и объединять деятельность ЦК и редакции «Искры». При выборах в центральные органы РСДРП сторонники Ленина и партии радикально-революционного типа получили большинство, за ними закрепилось название «большевики», а за сторонниками Мартова (на их позиции перешло и большинство «экономистов») – название «меньшевики» (названия условны, поскольку соотношение сил между фракциями «большевиков» и «меньшевиков» в РСДРП постоянно менялось). Ленин оценил разделение РСДРП на фракции как «прямое и неизбежное продолжение… разделения социал-демократии на революционную и оппортунистическую…» [«Шаг вперёд, два шага назад», опубликована в 1904 (Ленин В. И. ПСС. Т. 8. Москва, 1967. С. 330)]. С раскола РСДРП на II съезде Ленин вёл отсчёт истории российской коммунистической партии; по его словам, «большевизм существует, как течение политической мысли и как политическая партия, с 1903 года» (Ленин В. И. ПСС. Т. 41. Москва, 1981. С. 6). После съезда Ленин начал борьбу с меньшевизмом внутри РСДРП. Отстаивал собственную трактовку теории К. Маркса, иные поиски в этом направлении отвергал как «ревизионизм».

Вскоре Ленин заявил о своём выходе из редакции «Искры» [19 октября (1 ноября) 1903] в знак протеста против требования Г. В. Плеханова восстановить первоначальный состав редакции (в ноябре того же года все прежние редакторы, кроме Ленина, вошли в редколлегию). 8(21) ноября 1903 г. кооптирован в состав ЦК РСДРП после того, как в нём остались только его сторонники (от ЦК отделилась Заграничная лига РСДРП, признанная на II съезде единственной заграничной организацией партии). Однако в 1904 г. руководство во всех центральных органах РСДРП перешло к меньшевикам. В конце 1904 г. по инициативе и под руководством Ленина образован большевистский партийный центр – Бюро комитетов большинства (БКБ), который стал издавать в Женеве первую большевистскую газету «Вперёд» (декабрь 1904 – май 1905). Ленин выведен из состава ЦК РСДРП 7(20) февраля 1905 г.

Участие в Первой русской революции

Для выработки тактики большевиков в начавшейся революции 1905–1907 гг. Ленин созвал III (Лондонский) съезд РСДРП, фактически являвшийся конференцией его сторонников [12–27 апреля (25 апреля – 10 мая) 1905]; меньшевики отказались на ней присутствовать и провели свою конференцию отдельно, в Женеве. Участники III съезда РСДРП избрали большевистский ЦК (в него вошёл Ленин), в формулировке Ленина приняли первый параграф устава РСДРП. Под руководством Ленина в Женеве издавалась газета «Пролетарий» (май – ноябрь 1905).

В ноябре 1905 г., после издания Манифеста 17 октября 1905 г., Ленин возвратился в Санкт-Петербург и возглавил редакцию выходившей там легальной газеты «Новая жизнь» (опубликовал в ней несколько статей). Ход первой русской революции не вполне подтвердил ранние представления Ленина: обнаружилось, что рабочие способны к политической самоорганизации, это проявилось в создании Советов (их Ленин расценил как «революционное творчество» масс). Ленин продолжал настаивать на углублении революционного кризиса и в условиях либерализации режима, последовавшей за манифестами императора Николая II 1905 г. (подтверждены Основными государственными законами 1906 г.), в частности в условиях начала деятельности законодательной Государственной думы. Ленин одновременно с А. Л. Парвусом и Л. Д. Троцким выдвинул идею непрерывной революции – сближения её буржуазно-демократического и социалистического этапов. Развивая свои ранние взгляды, Ленин подверг критике меньшевиков, которые утверждали, что руководящей силой в Революции 1905–1907 гг. должна быть буржуазия («Две тактики социал-демократии в демократической революции», 1905). Он считал необходимым сломить силой сопротивление буржуазии и парализовать неустойчивость крестьянства и мелкой буржуазии, свергнуть самодержавие путём вооружённого восстания и установить новый тип власти – революционно-демократическую диктатуру пролетариата и крестьянства с участием в новом правительстве социал-демократов, но без либералов.

Ленин участвовал в работе собравшегося для преодоления раскола РСДРП объединительного съезда (апрель/май 1906, Стокгольм; преобладали меньшевики; в состав ЦК РСДРП Ленин не был избран). Под впечатлением от крестьянских выступлений во время Революции 1905–1907 гг. Ленин (как и все социал-демократы) признал ошибочным пункт аграрной программы РСДРП с требованием вернуть крестьянам только «отрезки» земли, принадлежавшие им до крестьянской реформы 1861 г. Стал настаивать на национализации всей земли (казённой, частновладельческой и пр.); в этом вопросе разошёлся с частью своих сторонников, поддерживавших идею экспроприации только помещичьих земель, и с меньшевиками, отстаивавшими программу муниципализации помещичьей земли, которую крестьяне будут арендовать у органов местного самоуправления. Участвуя в работе объединительного съезда, Ленин в то же время отказался пойти на идейный компромисс с меньшевиками, заявив: «Объединить две части – согласны. Спутать две части – никогда» (Ленин В. И. ПСС. Т. 47. Москва, 1970. С. 80).

Летом 1906 г. Ленин переехал в сравнительно безопасный для революционеров посёлок Куоккала Выборгского уезда Выборгской губернии Великого княжества Финляндского (ныне посёлок Репино Курортного района Санкт-Петербурга), редактировал издававшиеся в Санкт-Петербурге легальные большевистские газеты. Участвовал в работе Лондонского съезда РСДРП [30 апреля – 19 мая (13 мая – 1 июня) 1907; преобладали большевики]. На съезде, вопреки позиции меньшевиков, придававших работе в Государственной думе самодовлеющее значение, Ленин предлагал использовать её прежде всего как трибуну для пропаганды революционных требований партии. Считал, что деятельность социал-демократов в Думе (65 человек в 1907 – как большевики, так и меньшевики) должна быть подчинена внедумской работе. Избран кандидатом в члены ЦК РСДРП. Ленин возглавил новый руководящий орган своей фракции – т. н. Большевистский центр (упразднён в январе 1910).

Ленин участвовал в деятельности Второго интернационала (в 1905–1912 представлял РСДРП в его Международном социалистическом бюро), возглавлял большевистскую делегацию на Штутгартском (1907) и Копенгагенском (1910) конгрессах Второго интернационала. Поддерживал левые группы в социал-демократических партиях – германских левых, трибунистов в Нидерландах, тесняков в Болгарии и отдельных социалистов, выступавших за активизацию революционной борьбы масс, в том числе путём использования политических стачек по «русскому примеру».

Вторая эмиграция (1908–1917)

В декабре 1907 г. Ленин уехал в Женеву, в конце 1908 г. – в Париж. Подвергал критике т. н. ликвидаторов (часть меньшевиков, стремившихся превратить РСДРП в легальную рабочую партию), а также т. н. отзовистов (тех большевиков, которые считали необходимым отказаться от легальной деятельности, в частности отозвать социал-демократических депутатов из Государственной думы). Призывал использовать все формы работы, предпочтение отдавал нелегальным.

Уступая идущей снизу волне объединительных настроений в крайне ослабленной и малочисленной РСДРП, Ленин формально согласился с решением пленума ЦК РСДРП (январь 1910) о восстановлении единства партии на уровне постоянно функционировавших центральных органов за границей и в России (местные организации в значительной части оставались едиными) и упразднении своего Большевистского центра. На деле он взял курс на окончательное организационное размежевание с меньшевиками, критикуя Троцкого, а также большевиков А. И. Рыкова, В. П. Ногина, Л. Б. Каменева, Г. Е. Зиновьева, призывавших к объединению фракций в РСДРП.

С точки зрения «партийности» Ленин рассматривал всякое гуманитарное знание, особенно политическую экономию, а также философию, которая должна способствовать «изменению мира», быть связанной с революционной борьбой пролетариата («Материализм и эмпириокритицизм», издана легально в Москве в 1909). Сторонник материализма, Ленин выступал против эмпириокритицизма, философских взглядов Э. Маха, Р. Авенариуса, А. А. Богданова, С. А. Суворова и других российских и западноевропейских философов.

В 1911 г. Ленин организовал большевистскую партийную школу в Лонжюмо (близ Парижа), прочитал в ней 29 лекций. В январе 1912 г. созвал в Праге вместо планировавшейся общепартийной – фракционную конференцию большевиков – только своих сторонников (на ней не были представлены другие большевистские группы, а также меньшевики и национальные социал-демократические партии). Был избран в образованный на конференции большевистский ЦК [17(30) января 1912]. По инициативе Ленина с 22 апреля (5 мая) 1912 г. в Санкт-Петербурге стала выходить ежедневная легальная большевистская газета «Правда». Чтобы быть ближе к России и успешнее руководить партийной работой, в июне 1912 г. Ленин переехал в Краков (Австро-Венгрия; летом 1913 и летом 1914 Ленин с семьёй жил в деревне Белый Дунаец, в районе Поронина, близ Кракова). В 4-й Государственной думе по требованию Ленина депутаты-большевики в 1913 г. раскололи единую до этого времени социал-демократическую фракцию. Впоследствии (в мае/июне 1917, в письменных показаниях, данных Чрезвычайной следственной комиссии Временного правительства), говоря о событиях 1912–1913 гг., Ленин утверждал, что политическая линия большевиков, «ведущая прямо и неизбежно к расколу с оппортунистами-меньшевиками, вытекала сама собой» из истории РСДРП начиная с 1903 г. (Вопросы истории КПСС. 1990. № 11), а его ближайший соратник Г. Е. Зиновьев уже в советское время утверждал, что в Праге в 1912 г. Ленин добился «создания отдельной партии» (такой же точки зрения придерживался И. В. Сталин).

Одновременно Ленин обосновал большевистскую программу по национальному вопросу. Чтобы солидаризироваться с национальными социал-демократическими партиями (многие из них в своих программах содержали требование либо отделения, либо автономии в составе Российской империи) и в то же время не расколоть рабочее движение по национальному признаку, Ленин признал за нациями право на самоопределение вплоть до государственного отделения. Вместе с тем он подчёркивал, что такое право «непозволительно смешивать с вопросом о целесообразности отделения той или иной нации» (Ленин В. И. ПСС. Т. 24. Москва, 1973. С. 59), и рассматривал отделение как исключительный случай. Предпочтительным вариантом решения национального вопроса считал создание крупными нациями национально-территориальных автономий, а не культурно-национальных автономий, противоречащих пролетарскому интернационализму («Критические заметки по национальному вопросу», 1913). Борьбу за национальные интересы народов окраин Российской империи связывал с борьбой против самодержавия (доклад на совещании партийных работников в сентябре/октябре 1913 в Поронине).

В начале Первой мировой войны, 26 июля (8 августа) 1914 г., Ленин арестован австрийскими властями в Поронине по подозрению в шпионаже в пользу России, 6(19) августа освобождён в результате вмешательства австрийских социал-демократов, объяснивших своему правительству, что Ленин – злейший враг российской монархии. Выехал в нейтральную Швейцарию 23 августа (5 сентября) (сначала жил в Берне, в феврале 1916 переехал в Цюрих, где оставался до апреля 1917). Начавшаяся война вселила в него уверенность в близкой гибели не только российского самодержавия, но и всей мировой капиталистической системы. Ленин посчитал войну последним и неопровержимым доказательством исчерпанности прогрессивного потенциала капиталистической экономики и буржуазной демократии. Он полагал, что повсеместный патриотический подъём начального этапа войны – преходящее явление, рано или поздно, но пролетариат поддержит интернационалистов. Пытался, основываясь на марксистском постулате «рабочие не имеют отечества», согласовать принятую большевиками тактику пораженчества с распространившимся народным патриотизмом («О национальной гордости великороссов», декабрь 1914). Выдвинул лозунг превратить войну империалистическую в войну гражданскую и призвал социал-демократов воевавших стран содействовать поражению своих правительств. Их переход на позиции «оборончества» (отказ на время войны от выступлений против своих правительств в революционной или легально-оппозиционной форме) Ленин расценил как крах Второго интернационала, считал, что его левые элементы – подлинные интернационалисты – должны осуществить, подобно большевикам, раскол в каждой из входивших в Интернационал партий. Он утвердился во мнении о необходимости окончательно порвать с социал-демократией – не только российской, но и всей европейской, изменившей марксизму (за «войну до победного конца» высказались конференции социалистов стран Антанты в Лондоне в феврале 1915 и стран германо-австрийского блока в Вене в апреле 1915). Отстаивал свою позицию на проходившей под его руководством Бернской конференции заграничных секций РСДРП (март 1915), на международных социалистических конференциях в Циммервальде (сентябрь 1915) и Кинтале (апрель 1916).

Пришёл к выводу, что в «эпоху империализма» (новая, сложившаяся после К. Маркса, реальность) из-за неравномерности экономического и политического развития капитализма победа социализма возможна первоначально в немногих или даже в одной, отдельно взятой, капиталистической стране – т. н. слабом звене в цепи империализма. Доказывал, что в социальной и экономической структуре передовых капиталистических стран с переходом к империализму произошли качественные изменения, которые привели «к самому всестороннему обобществлению производства»; монополистический капитализм «втаскивает… капиталистов, вопреки их воли и сознания, в какой-то новый общественный порядок, переходный от полной свободы конкуренции к полному обобществлению» (Ленин В. И. ПСС. Т. 27. Москва, 1969. С. 320–321). Капитализм, утверждал Ленин, вступил на рубеже 19–20 вв. в последнюю стадию своего развития, в империализм – «загнивающий» капитализм, канун социалистической революции («Империализм, как высшая стадия капитализма»; книга написана в 1916, впервые опубликована в 1917). Вместе с тем Ленин отводил достаточно длительный срок до начала революции. По его прогнозам, до неё оставалось 5, 10 и более лет.

В период от Февраля к Октябрю

Узнав о начале Февральской революции 1917 г., отречении 2(15) марта 1917 г. императора Николая II от престола и приходе к власти Временного правительства (действовало наряду с Советами во главе с Петросоветом, что давало Ленину основание говорить о двоевластии), Ленин вновь обратился к идее непосредственного перехода от буржуазно-демократического этапа революции к социалистическому, считал, что теперь его должны возглавить большевики («Письма из далека», март 1917). После возвращения в Россию 3(16) апреля 1917 г. (через Германию с разрешения её правительства в специальном вагоне вместе с другими политическими эмигрантами) Ленин на следующий день изложил основные положения большевистской стратегии и тактики перед своими сторонниками (т. н. Апрельские тезисы).

На 1-м Всероссийском съезде Советов рабочих и солдатских депутатов [3–24 июня (16 июня – 7 июля) 1917, Петроград] Ленин в числе большевиков и представителей других социалистических партий избран членом ВЦИК Советов, однако резолюцию большевиков о переходе власти к Советам съезд отклонил, приняв резолюцию о поддержке коалиционного (многопартийного) Временного правительства. 4(17) июня там же на съезде в ответ на заявление меньшевика И. Г. Церетели о том, что в России нет политической партии, которая одна была бы готова взять власть от Временного правительства в свои руки, Ленин, имея в виду большевиков, сказал: «Я отвечаю: «есть! Ни одна партия от этого отказаться не может, и наша партия от этого не отказывается: каждую минуту она готова взять власть целиком»» (Ленин В. И. ПСС. Т. 32. Москва, 1969. С. 267).

В обоснование идеи перехода революции в социалистическую стадию Ленин в апреле–июле 1917 г. написал свыше 170 статей, брошюр, воззваний, проектов резолюций большевистских конференций и ЦК большевиков, постоянно выступал на собраниях и митингах. После июльских событий 1917 г. (проходили под лозунгом «Вся власть Советам!») Временное правительство 7(20) июля отдало приказ об аресте Ленина, обвинив большевиков в организации восстания, соглашении с агентами Германии в целях дезорганизации фронта и тыла, использовании в своей деятельности немецкой финансовой поддержки. Ленин перешёл на нелегальное положение, до 8(21) августа скрывался у озера Разлив, близ Петрограда, затем до начала октября – в Финляндии (Ялкала, Гельсингфорс, Выборг). Продолжал осуществлять общее руководство партией большевиков в условиях, когда конфронтация с «властью буржуазии» обеспечила большевикам выигрышное положение непричастных к деятельности Временного правительства, тогда как «соглашатели» – эсеры и меньшевики – оказались в положении ответственных за замораживание главных проблем того времени. По указанию Ленина съезд партии [26 июля – 3 августа (8–16 августа) 1917, Петроград; фактически первый съезд большевиков, в советской историографии за ним утвердилось обозначение VI съезд РСДРП(б)] отказался на время от лозунга «Вся власть Советам!». Съезд принял решение о неявке Ленина на суд в связи с распоряжением Временного правительства о его аресте, а также избрал ЦК, в состав которого вновь вошёл Ленин. Во время выступления Корнилова 1917 г. (август/сентябрь) Ленин писал в ЦК: «…мы воюем с Корниловым, как и войска Керенского, но мы не поддерживаем Керенского… мы видоизменяем форму нашей борьбы с Керенским… развитие этой войны одно только может нас привести к власти» (Ленин В. И. ПСС. Т. 34. Москва, 1969. С. 120–121).

В подполье в августе–сентябре 1917 г. Ленин написал книгу «Государство и революция» (впервые опубликована в мае 1918 в Петрограде; материалы к ней Ленин готовил в январе–феврале 1917 в Швейцарии) – своё толкование взглядов К. Маркса и Ф. Энгельса в виде комментария к их высказываниям о новом государстве, которое должно быть создано взамен старого в результате социалистической революции. С переходом к империализму, утверждал он, парламентаризм изжил себя, а гражданское равенство стало формальным; по мнению Ленина, государство диктатуры пролетариата будет властью демократической для неимущих и диктаторской по отношению к буржуазии. Он писал о неизбежном отмирании государства, его началом считал привлечение всё большего числа граждан, а затем и поголовно всех к управлению государством. Это представлялось Ленину возможным, т. к. благодаря «капиталистической культуре» громадное большинство функций управления якобы упростилось настолько, что они стали доступны всем грамотным людям. Ленин считал возможным упразднить в новом государстве армию, полицию, бюрократию и пр. Он наметил экономическую программу и неотложные мероприятия по борьбе с хозяйственной разрухой после прихода большевиков к власти (рабочий контроль над производством и распределением продуктов, национализация банков и крупнейших капиталистических монополий, конфискация помещичьей земли и национализация всей земли в стране и др.) («Грозящая катастрофа и как с ней бороться», 1917).

В событиях Октябрьской революции 1917 г. Ленин сыграл главную роль. 12–14 (25–27) сентября 1917 г. он написал письмо ЦК большевиков, Петроградскому и Московскому комитетам партии «Большевики должны взять власть» и письмо в ЦК РСДРП(б) «Марксизм и восстание». В письмах Ленин, отметив, что большевики получили большинство в Петроградском и Московском Советах и что «большинство народа за нас» (в некоторых работах того же времени он писал «не народ, но авангард»), предложил начать немедленную подготовку к вооружённому восстанию для свержения Временного правительства. ЦК отклонил это предложение (Ленин в знак протеста вышел из состава ЦК), впоследствии Ленин также расценил его как преждевременное. Однако он и его соратники, уверенные, что революции во всех странах, участвовавших в войне, не за горами, не отказались от идеи вооружённого восстания в обстановке всеобщего разочарования политикой Временного правительства.

Придя к выводу, что по вопросу о восстании «замечается какое-то равнодушие» (ПСС. Т. 34. С. 391), Ленин тайно в конце сентября – начале октября приехал из Выборга в Петроград, чтобы агитировать за немедленное вооружённое восстание. При поддержке Л. Д. Троцкого (к тому времени уже примкнул к большевикам) и вопреки возражениям Л. Б. Каменева и Г. Е. Зиновьева, Ленин на заседании ЦК 10(23) октября добился принятия решения о практической подготовке вооружённого восстания (в тот же день избран членом Политбюро, созданного как временный орган на период подготовки восстания). Это решение подтверждено на расширенном заседании ЦК большевиков 16(29) октября после того, как Ленин убедил руководство и актив партии не ожидать, как предлагал Троцкий, открытия в здании бывшего Смольного института 2-го Всероссийского съезда Советов рабочих и солдатских депутатов [было назначено на 20 октября (2 ноября), а затем перенесено на 25 октября (7 ноября)]. Тогда же для руководства восстанием создан Военно-революционный центр большевиков (А. С. Бубнов, Ф. Э. Дзержинский, Я. М. Свердлов, И. В. Сталин, М. С. Урицкий), вошедший в состав образованного из большевиков, левых эсеров и представителей других революционных организаций Петроградского военно-революционного комитета (ПВРК). 24 октября (6 ноября), накануне открытия 2-го Всероссийского съезда Советов, в письме в ЦК большевиков Ленин потребовал немедленно перейти в наступление, арестовать Временное правительство и взять власть, подчёркивая, что «промедление в выступлении смерти подобно». Вечером того же дня нелегально прибыл в здание бывшего Смольного института, где находился ПВРК, настаивал на штурме Зимнего дворца и аресте Временного правительства до открытия 2-го Всероссийского съезда Советов. Написал воззвание «К гражданам России» (в нём сообщалось, что Временное правительство низложено, хотя оно ещё и оставалось у власти), с которым утром 25 октября (7 ноября) ПВРК через радиостанцию крейсера «Аврора» обратился к населению России, днём в тот же день Ленин выступил с докладом о задачах советской власти на экстренном заседании Петроградского Совета. Вечером 25 октября (7 ноября) Ленин, находившийся в Смольном, но отсутствовавший в зале заседаний 2-го Всероссийского съезда Советов, вновь потребовал от ПВРК немедленного ареста Временного правительства (ночью министров арестовали в Зимнем дворце). Автор принятого на съезде утром 26 октября (8 ноября) обращения «Рабочим, солдатам и крестьянам!», в котором сообщалось, что Временное правительство низложено, говорилось о прекращении полномочий ВЦИК Советов и переходе власти к Съезду Советов, а на местах – к Советам. По докладам Ленина в тот же день на Съезде приняты Декрет о мире и Декрет о земле. В ночь на 27 октября (9 ноября) из большевиков (получили поддержку 225 из 402 Советов, представленных на съезде) было сформировано временное, до созыва Учредительного собрания, правительство – Совет народных комиссаров (СНК) во главе с Лениным, который отказался от возможности создания правительственной коалиции социалистических партий.

В годы Гражданской войны

Ленин и его соратники удержали власть во время начавшейся Гражданской войны 1917–1922 гг., а затем и иностранной военной интервенции в России 1918–1922 гг. В первые же дни после образования СНК Ленин столкнулся с попытками отстранения большевиков от власти, с одной стороны, сторонниками Временного правительства (в ходе выступления Керенского – Краснова 1917), с другой – Всероссийским исполнительным комитетом профсоюза железнодорожников (Викжелем), потребовавшим под угрозой всеобщей забастовки на железных дорогах создания «однородного социалистического правительства» из представителей всех социалистических партий. Ленин вступил в переговоры с Викжелем (рассматривал их «как дипломатическое прикрытие военных действий»), однако после подавления выступления Керенского – Краснова в состав СНК вошли только левые эсеры. Свергая в октябре 1917 г. Временное правительство под флагом устранения последнего препятствия к созыву Учредительного собрания (один из главных программных и тактических лозунгов большевиков), Ленин выразил готовность признать любые результаты выборов в него, однако настоял на роспуске Учредительного собрания [6(19) января 1918], когда выборы дали перевес эсерам (39,5% против 22,5% у большевиков). Первостепенное значение с первых дней прихода к власти Ленин стал придавать формированию нового государственного аппарата, армии и органов подавления сопротивления революционной власти (инициатор основных решений СНК, в октябре 1917 – ноябре 1918 подписал свыше 3 тыс. декретов, автор многих из них), отодвигая всё дальше на неопределённое будущее сформулированную им накануне Октябрьской революции идею «государства-коммуны». По предложению Ленина в декабре 1917 г. создана Всероссийская чрезвычайная комиссия (ВЧК), в январе 1918 г. он возглавил разработку декрета об организации Рабоче-Крестьянской Красной Армии. Одобрил произведённый в Екатеринбурге расстрел бывшего императора Николая II и его семьи.

Новая государственная структура, вопреки заявлениям Ленина о полном разрыве с прошлым, приобретала черты традиционного государства, однако при этом уничтожались сложившиеся к 1917 г. элементы гражданского общества и правовые основы государственности. Ленин характеризовал советское государство того периода как «ничем не ограниченную, никакими законами, никакими абсолютно правилами не стеснённую, непосредственно на насилие опирающуюся власть» (Ленин В. И. ПСС. Т. 41. Москва, 1981. С. 383). Снижалась роль Советов, которые всё больше превращались в декоративное прикрытие однопартийного режима. О том, что в Советской России правят не Советы, а партия большевиков, всё чаще говорил и сам Ленин.

В момент очередной острой угрозы для власти большевиков, теперь со стороны Германии, Ленин добился заключения с ней сепаратного Брестского мира 1918 г. При этом ему удалось преодолеть сопротивление «левых коммунистов», требовавших, как и левые эсеры (в то время ещё союзники большевиков), объявить революционную войну международному империализму. В полемике с противниками подписания мира Ленин доказывал, что он будет непродолжительным в связи с неизбежностью революции в Германии и не означает отказа большевиков от идеи мировой революции (Брестский мир аннулирован РСФСР 13 ноября 1918 в связи с Ноябрьской революцией 1918 в Германии). По предложению Ленина СНК и ЦК РКП(б) переехали в марте 1918 г. в Москву, в Кремль (там же находились рабочий кабинет и квартира Ленина).

Экономическая программа, которую Ленин предложил в конце лета – начале осени 1917 г. в качестве радикального средства спасения страны, была выполнена, однако национализация банков, крупных предприятий, транспорта путём «красногвардейской атаки на капитал» и введение рабочего контроля на предприятиях не изменили к лучшему экономическое положение в стране. Ленин призвал рабочий класс организовать «крестовый поход» против «дезорганизаторов» и против «укрывателей хлеба» – зажиточных крестьян (кулаков), в которых видел главных врагов социализма. Он подписал декреты ВЦИК и СНК от 13 и 27 мая 1918 г. о введении продовольственной диктатуры, положившие начало политике «военного коммунизма». Несмотря на экономическую несостоятельность этой политики (вместе с тем она сыграла определённую роль в достижении перелома в пользу Красной Армии в Гражданской войне 1917–1922), Ленин до 1921 г. продолжал считать её единственно верной. Он одобрил апологетику политики «военного коммунизма» в книге Н. И. Бухарина «Экономика переходного периода» (1920), в том числе его тезис о «пролетарском принуждении» во всех его формах – от расстрелов до трудовой повинности – как методе «выработки коммунистического человечества из человеческого материала капиталистической эпохи» (Бухарин Н. И. Избранные произведения. Москва, 1990. С. 198). Государственное регулирование экономики, попытка регулирования социальных отношений сопровождались значительным ростом государственного аппарата (число служащих в короткий срок превысило те же показатели в дореволюционной России). Его хроническую неэффективность Ленин пытался компенсировать требовательностью к подчинённым, собственной организованностью и нечеловеческой, по словам М. Горького, работоспособностью. Он участвовал в обсуждении и проведении в жизнь бесчисленного количества дел, вплоть до мелких и мельчайших, свыше 400 раз председательствовал на заседаниях СНК. Борьба с бюрократизмом стала лейтмотивом выступлений Ленина до конца его жизни.

Насилие Ленин рассматривал как необходимую и оправданную составную часть защиты революции. Осенью 1918 г., после восстания левых эсеров 1918 г., покушений на большевистских руководителей и на самого Ленина (30 августа 1918), он возвёл террор, получивший название «красный террор», в ранг государственной политики. Расстреливали не только активных противников советской власти, но и многих представителей слоёв, которые назывались «бывшими» (дворяне, духовные лица, предприниматели и т. д.).

Ленин возглавил Совет рабочей и крестьянской обороны (с 1920 Совет труда и обороны) – главный военно-хозяйственный орган РСФСР, созданный 30 ноября 1918 г. во исполнение декрета ВЦИК от 2 сентября 1918 г., которым Советская Республика объявлялась военным лагерем. В идеологической сфере Ленин заложил основы и обосновал задачи культурной революции. Ленин подверг резкой критике основные тезисы брошюры К. Каутского «Диктатура пролетариата» (1918), обвинившего большевиков в уничтожении демократии, осуществлении диктатуры меньшинства, порождающей гражданскую войну, и утверждавшего, что социализм как средство освобождения пролетариата немыслим без демократии. Ленин утверждал, что революционное насилие пролетариата над буржуазией – абсолютно необходимое условие осуществления пролетарской революции, что она дала «невиданное в мире развитие и расширение демократии именно для гигантского большинства населения, для эксплуатируемых и трудящихся» (Ленин В. И. ПСС. Т. 37. Москва, 1969. С. 256). Выразил уверенность, что «не только общеевропейская, но мировая пролетарская революция зреет у всех на глазах, и ей помогла, её ускорила, её поддержала победа пролетариата в России» (Ленин В. И. ПСС. Т. 37. С. 305). Позднее, в речи на III Всероссийском съезде Российского коммунистического союза молодёжи 2 октября 1920 г., Ленин, говоря о коммунистической морали, подчёркивал, что «нравственность выводится из интересов классовой борьбы пролетариата».

В. И. Ленин, планы выступлений. Видео предоставлено кинокомпанией «Православная энциклопедия».

Видео предоставлено кинокомпанией «Православная энциклопедия»