| Arabic: | الجمعية العامة للأمم المتحدة |

|---|---|

| Chinese: | 联合国大会 |

| Hindi: | संयुक्त राष्ट्र महासभा |

| French: | Assemblée générale des Nations unies |

| Russian: | Генеральная Ассамблея Организации Объединённых Наций |

| Spanish: | Asamblea General de las Naciones Unidas |

Emblem of the United Nations General Assembly

United Nations General Assembly Hall at the UN Headquarters in New York City in 2006

- GA

- UNGA

- AG

Head

(President)

Parent organization

| Membership and participation |

|---|

|

For two articles dealing with the membership of and participation in the General Assembly, see:

|

The United Nations General Assembly (UNGA or GA; French: Assemblée générale, AG) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN), serving as its main deliberative, policymaking, and representative organ. Currently in its 78th session, its powers, composition, functions, and procedures are set out in Chapter IV of the United Nations Charter. The UNGA is responsible for the UN budget, appointing the non-permanent members to the Security Council, appointing the UN secretary-general, receiving reports from other parts of the UN system, and making recommendations through resolutions.[1] It also establishes numerous subsidiary organs to advance or assist in its broad mandate.[2] The UNGA is the only UN organ where all member states have equal representation.

The General Assembly meets under its President or the UN secretary-general in annual sessions at the General Assembly Building, within the UN headquarters in New York City. The main part of these meetings generally runs from September through part of January until all issues are addressed, which is often before the next session starts.[3] It can also reconvene for special and emergency special sessions. The first session was convened on 10 January 1946 in the Methodist Central Hall in London and included representatives of the 51 founding nations.

Most questions are decided in the General Assembly by a simple majority. Each member country has one vote. Voting on certain important questions—namely recommendations on peace and security; budgetary concerns; and the election, admission, suspension, or expulsion of members—is by a two-thirds majority of those present and voting. Apart from the approval of budgetary matters, including the adoption of a scale of assessment, Assembly resolutions are not binding on the members. The Assembly may make recommendations on any matters within the scope of the UN, except matters of peace and security under the Security Council’s consideration.

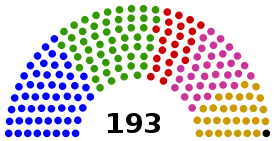

During the 1980s, the Assembly became a forum for «North-South dialogue» between industrialized nations and developing countries on a range of international issues. These issues came to the fore because of the phenomenal growth and changing makeup of the UN membership. In 1945, the UN had 51 members, which by the 21st century nearly quadrupled to 193, of which more than two-thirds are developing. Because of their numbers, developing countries are often able to determine the agenda of the Assembly (using coordinating groups like the G77), the character of its debates, and the nature of its decisions. For many developing countries, the UN is the source of much of their diplomatic influence and the principal outlet for their foreign relations initiatives.

Although the resolutions passed by the General Assembly do not have the binding forces over the member nations (apart from budgetary measures), pursuant to its Uniting for Peace resolution of November 1950 (resolution 377 (V)), the Assembly may also take action if the Security Council fails to act, owing to the negative vote of a permanent member, in a case where there appears to be a threat to the peace, breach of the peace or act of aggression. The Assembly can consider the matter immediately with a view to making recommendations to Members for collective measures to maintain or restore international peace and security.[4]

History[edit]

The first session of the UN General Assembly was convened on 10 January 1946 in the Methodist Central Hall in London and included representatives of 51 nations.[5] Until moving to its permanent home in Manhattan in 1951, the Assembly convened at the former New York City Pavilion of the 1939 New York World’s Fair in Flushing, New York.[6] On November 29, 1947, the Assembly voted to adopt the United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine at this venue.[7]

During the 1946-1951 period the General Assembly, the Security Council and the Economic Social Council also conducted proceedings at the United Nations interim headquarters at Lake Success, New York.[8][9] During this time in 1949, the CBS Television network provided live coverage of these sessions on its United Nations in Action broadcast series which was produced by the journalist Edmund Chester.[10]

It moved to the permanent Headquarters of the United Nations in New York City at the start of its seventh regular annual session, on 14 October 1952. In December 1988, in order to hear Yasser Arafat, the General Assembly organized its 29th session in the Palace of Nations, in Geneva, Switzerland.[11]

Membership[edit]

All 193 members of the United Nations are members of the General Assembly, with the addition of the Holy See and Palestine as observer states as well as the European Union (since 1974). Further, the United Nations General Assembly may grant observer status to an international organization or entity, which entitles the entity to participate in the work of the United Nations General Assembly, though with limitations.

Agenda[edit]

The agenda for each session is planned up to seven months in advance and begins with the release of a preliminary list of items to be included in the provisional agenda.[12] This is refined into a provisional agenda 60 days before the opening of the session. After the session begins, the final agenda is adopted in a plenary meeting which allocates the work to the various main committees, who later submit reports back to the Assembly for adoption by consensus or by vote.

Items on the agenda are numbered. Regular plenary sessions of the General Assembly in recent years have initially been scheduled to be held over the course of just three months; however, additional workloads have extended these sessions until just short of the next session. The routinely scheduled portions of the sessions normally commence on «the Tuesday of the third week in September, counting from the first week that contains at least one working day», per the UN Rules of Procedure.[13] The last two of these Regular sessions were routinely scheduled to recess exactly three months afterward[14] in early December but were resumed in January and extended until just before the beginning of the following sessions.[15]

Resolutions[edit]

The General Assembly votes on many resolutions brought forth by sponsoring states. These are generally statements symbolizing the sense of the international community about an array of world issues.[16] Most General Assembly resolutions are not enforceable as a legal or practical matter, because the General Assembly lacks enforcement powers with respect to most issues.[17] The General Assembly has the authority to make final decisions in some areas such as the United Nations budget.[18]

The General Assembly can also refer an issue to the Security Council to put in place a binding resolution.[19]

Resolution numbering scheme[edit]

From the First to the Thirtieth General Assembly sessions, all General Assembly resolutions were numbered consecutively, with the resolution number followed by the session number in Roman numbers (for example, Resolution 1514 (XV), which was the 1514th numbered resolution adopted by the Assembly, and was adopted at the Fifteenth Regular Session (1960)). Beginning in the Thirty-First Session, resolutions are numbered by individual session (for example Resolution 41/10 represents the 10th resolution adopted at the Forty-First Session).[citation needed]

Budget[edit]

The General Assembly also approves the budget of the United Nations and decides how much money each member state must pay to run the organization.[20]

The Charter of the United Nations gives responsibility for approving the budget to the General Assembly (Chapter IV, Article 17) and for preparing the budget to the secretary-general, as «chief administrative officer» (Chapter XV, Article 97). The Charter also addresses the non-payment of assessed contributions (Chapter IV, Article 19).

The planning, programming, budgeting, monitoring, and evaluation cycle of the United Nations has evolved over the years; major resolutions on the process include General Assembly resolutions: 41/213 of 19 December 1986, 42/211 of 21 December 1987, and 45/248 of 21 December 1990.[21]

The budget covers the costs of United Nations programmes in areas such as political affairs, international justice and law, international cooperation for development, public information, human rights, and humanitarian affairs.

The main source of funds for the regular budget is the contributions of member states. The scale of assessments is based on the capacity of countries to pay. This is determined by considering their relative shares of total gross national product, adjusted to take into account a number of factors, including their per capita incomes.

In addition to the regular budget, member states are assessed for the costs of the international tribunals and, in accordance with a modified version of the basic scale, for the costs of peacekeeping operations.[22]

Elections[edit]

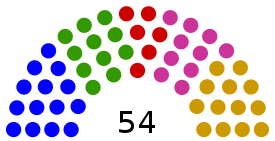

The Group of African States (54)

The Group of Asia-Pacific States (54)

The Group of Eastern European States (23)

The Group of Latin American and Caribbean States (33)

The Group of Western European and Other States (28)

No group

The General Assembly is entrusted in the United Nations Charter with electing members to various organs within the United Nations system. The procedure for these elections can be found in Section 15 of the Rules of Procedure for the General Assembly. The most important elections for the General Assembly include those for the upcoming President of the General Assembly, the Security Council, the Economic and Social Council, the Human Rights Council, the International Court of Justice, judges of the United Nations Dispute Tribunal, and United Nations Appeals Tribunal. Most elections are held annually, with the exception of the election of judges to the ICJ, which happens triennially.[23][24]

The Assembly annually elects five non-permanent members of the Security Council for two-year terms, 18 members of the Economic and Social Council for three-year terms, and 14–18 members of the Human Rights Council for three-year terms. It also elects the leadership of the next General Assembly session, i.e. the next President of the General Assembly, the 21 Vice-Presidents, and the bureaux of the six main committees.[23][25][26]

Elections to the International Court of Justice take place every three years in order to ensure continuity within the court. In these elections, five judges are elected for nine-year terms. These elections are held jointly with the Security Council, with candidates needing to receive an absolute majority of the votes in both bodies.[27]

The Assembly also, in conjunction with the Security Council, selects the next secretary-general of the United Nations. The main part of these elections is held in the Security Council, with the General Assembly simply appointing the candidate that receives the Council’s nomination.[28]

Regional groups[edit]

African States (14)

Asia-Pacific States (11)

Eastern European States (6)

Latin American and Caribbean States (10)

Western European and Other States (13)

The United Nations Regional Groups were created in order to facilitate the equitable geographical distribution of seats among the Member States in different United Nations bodies. Resolution 33/138 of the General Assembly states that «the composition of the various organs of the United Nations should be so constituted as to ensure their representative character.» Thus, member states of the United Nations are informally divided into five regions, with most bodies in the United Nations system having a specific number of seats allocated for each regional group. Additionally, the leadership of most bodies also rotates between the regional groups, such as the presidency of the General Assembly and the chairmanship of the six main committees.[28][29][30]

The regional groups work according to the consensus principle. Candidates who are endorsed by them are, as a rule, elected by the General Assembly in any subsequent elections.[30]

Sessions[edit]

Regular sessions[edit]

The General Assembly meets annually in a regular session that opens on the third Tuesday of September, and runs until the following September. Sessions are held at United Nations Headquarters in New York unless changed by the General Assembly by a majority vote.[23][31]

The regular session is split into two distinct periods, the main and resumed parts of the session. During the main part of the session, which runs from the opening of the session until Christmas break in December, most of the work of the Assembly is done. This period is the Assembly’s most intense period of work and includes the general debate and the bulk of the work of the six Main Committees. The resumed part of the session, however, which runs from January until the beginning of the new session, includes more thematic debates, consultation processes and working group meetings.[32]

General debate[edit]

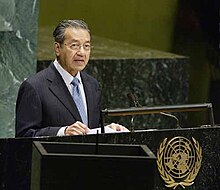

The general debate of each new session of the General Assembly is held the week following the official opening of the session, typically the following Tuesday, and is held without interruption for nine working days. The general debate is a high-level event, typically attended by Member States’ Heads of State or Government, government ministers and United Nations delegates. At the general debate, Member States are given the opportunity to raise attention to topics or issues that they feel are important. In addition to the general debate, there are also many other high-level thematic meetings, summits and informal events held during general debate week.[34][35][36]

The General debate is held in the United Nations General Assembly Hall at the United Nations Headquarters in New York.

Special sessions[edit]

Special sessions, or UNGASS, may be convened in three different ways, at the request of the Security Council, at the request of a majority of United Nations members States or by a single member, as long as a majority concurs. Special sessions typically cover one single topic and end with the adoption of one or two outcome documents, such as a political declaration, action plan or strategy to combat said topic. They are also typically high-level events with participation from heads of state and government, as well as by government ministers. There have been 30 special sessions in the history of the United Nations.[32][37][38]

Emergency special sessions[edit]

If the Security Council is unable, usually due to disagreement among the permanent members, to come to a decision on a threat to international peace and security, then emergency special sessions can be convened in order to make appropriate recommendations to Members States for collective measures. This power was given to the Assembly in Resolution 377(V) of 3 November 1950.[32][39][40]

Emergency special sessions can be called by the Security Council, if supported by at least seven members, or by a majority of Member States of the United Nations. If enough votes are had, the Assembly must meet within 24 hours, with Members being notified at least twelve hours before the opening of the session. There have been 11 emergency special sessions in the history of the United Nations.[23]

Subsidiary organs[edit]

The General Assembly subsidiary organs are divided into five categories: committees (30 total, six main), commissions (six), boards (seven), councils (four) and panels (one), working groups, and «other».

Committees[edit]

Main committees[edit]

The main committees are ordinally numbered, 1–6:[41]

- The First Committee: Disarmament and International Security is concerned with disarmament and related international security questions

- The Second Committee: Economic and Financial is concerned with economic questions

- The Third Committee: Social, Cultural, and Humanitarian deals with social and humanitarian issues

- The Fourth Committee: Special Political and Decolonisation deals with a variety of political subjects not dealt with by the First Committee, as well as with decolonization

- The Fifth Committee: Administrative and Budgetary deals with the administration and budget of the United Nations

- The Sixth Committee: Legal deals with legal matters

The roles of many of the main committees have changed over time. Until the late 1970s, the First Committee was the Political and Security Committee and there was also a sufficient number of additional «political» matters that an additional, unnumbered main committee, called the Special Political Committee, also sat. The Fourth Committee formerly handled Trusteeship and Decolonization matters. With the decreasing number of such matters to be addressed as the trust territories attained independence and the decolonization movement progressed, the functions of the Special Political Committee were merged into the Fourth Committee during the 1990s.

Each main committee consists of all the members of the General Assembly. Each elects a chairman, three vice chairmen, and a rapporteur at the outset of each regular General Assembly session.

Other committees[edit]

These are not numbered. According to the General Assembly website, the most important are:[41]

- Credentials Committee – This committee is charged with ensuring that the diplomatic credentials of all UN representatives are in order. The Credentials Committee consists of nine Member States elected early in each regular General Assembly session.

- General Committee – This is a supervisory committee entrusted with ensuring that the whole meeting of the Assembly goes smoothly. The General Committee consists of the president and vice presidents of the current General Assembly session and the chairman of each of the six Main Committees.

Other committees of the General Assembly are enumerated.[42]

Commissions[edit]

There are six commissions:[43]

- United Nations Disarmament Commission, established by GA Resolution 502 (VI) and S-10/2

- International Civil Service Commission, established by GA Resolution 3357 (XXIX)

- International Law Commission, established by GA Resolution 174 (II)

- United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL), established by GA Resolution 2205 (XXI)

- United Nations Conciliation Commission for Palestine, established by GA Resolution 194 (III)

- United Nations Peacebuilding Commission, established by GA Resolution 60/180 and UN Security Council Resolutions 1645 (2005) and 1646 (2005)

Despite its name, the former United Nations Commission on Human Rights (UNCHR) was actually a subsidiary body of ECOSOC.

Boards[edit]

There are seven boards which are categorized into two groups:

a) Executive Boards and b) Boards[44]

Executive Boards[edit]

- Executive Board of the United Nations Children’s Fund, established by GA Resolution 57 (I) and 48/162

- Executive Board of the United Nations Development Programme and of the United Nations Population Fund, established by GA Resolution 2029 (XX) and 48/162

- Executive Board of the World Food Programme, established by GA Resolution 50/8

Boards[edit]

- Board of Auditors, established by GA Resolution 74 (I)

- Trade and Development Board, established by GA Resolution 1995 (XIX)

- United Nations Joint Staff Pension Board, established by GA Resolution 248 (III)

- Advisory Board on Disarmament Matters, established by GA Resolution 37/99 K

Councils and panels[edit]

The newest council is the United Nations Human Rights Council, which replaced the aforementioned UNCHR in March 2006.

There are a total of four councils and one panel.[45]

Working Groups and other[edit]

There is a varied group of working groups and other subsidiary bodies.[46]

Seating[edit]

Countries are seated alphabetically in the General Assembly according to English translations of the countries’ names. The country which occupies the front-most left position is determined annually by the secretary-general via ballot draw. The remaining countries follow alphabetically after it.[47]

Reform and UNPA[edit]

On 21 March 2005, Secretary-General Kofi Annan presented a report, In Larger Freedom, that criticized the General Assembly for focusing so much on consensus that it was passing watered-down resolutions reflecting «the lowest common denominator of widely different opinions».[48] He also criticized the Assembly for trying to address too broad an agenda, instead of focusing on «the major substantive issues of the day, such as international migration and the long-debated comprehensive convention on terrorism». Annan recommended streamlining the General Assembly’s agenda, committee structure, and procedures; strengthening the role and authority of its president; enhancing the role of civil society; and establishing a mechanism to review the decisions of its committees, in order to minimize unfunded mandates and micromanagement of the United Nations Secretariat. Annan reminded UN members of their responsibility to implement reforms, if they expect to realize improvements in UN effectiveness.[49]

The reform proposals were not taken up by the United Nations World Summit in September 2005. Instead, the Summit solely affirmed the central position of the General Assembly as the chief deliberative, policymaking and representative organ of the United Nations, as well as the advisory role of the Assembly in the process of standard-setting and the codification of international law. The Summit also called for strengthening the relationship between the General Assembly and the other principal organs to ensure better coordination on topical issues that required coordinated action by the United Nations, in accordance with their respective mandates.[50]

A United Nations Parliamentary Assembly, or United Nations People’s Assembly (UNPA), is a proposed addition to the United Nations System that eventually could allow for direct election of UN parliament members by citizens all over the world.

In the General Debate of the 65th General Assembly, Jorge Valero, representing Venezuela, said «The United Nations has exhausted its model and it is not simply a matter of proceeding with reform, the twenty-first century demands deep changes that are only possible with a rebuilding of this organisation.» He pointed to the futility of resolutions concerning the Cuban embargo and the Middle East conflict as reasons for the UN model having failed. Venezuela also called for the suspension of veto rights in the Security Council because it was a «remnant of the Second World War [it] is incompatible with the principle of sovereign equality of States».[51]

Reform of the United Nations General Assembly includes proposals to change the powers and composition of the U.N. General Assembly. This could include, for example, tasking the Assembly with evaluating how well member states implement UNGA resolutions,[52] increasing the power of the assembly vis-à-vis the United Nations Security Council, or making debates more constructive and less repetitive.[53]

Sidelines of the General Assembly[edit]

The annual session of the United Nations General Assembly is accompanied by independent meetings between world leaders, better known as meetings taking place on the sidelines of the Assembly meeting. The diplomatic congregation has also since evolved into a week attracting wealthy and influential individuals from around the world to New York City to address various agendas, ranging from humanitarian and environmental to business and political.[54]

See also[edit]

- History of the United Nations

- List of current permanent representatives to the United Nations

- Reform of the United Nations

- United Nations Interpretation Service

- United Nations System

References[edit]

- ^ Charter of the United Nations: Chapter IV Archived 12 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine. United Nations.

- ^ General Assembly: Subsidiary organs at UN.org.

- ^ United Nations Official Document. «The annual session convenes on Tuesday of the third week in September per Resolution 57/301, Para. 1. The opening debate begins the following Tuesday». www.un.org.

- ^ General Assembly of the United Nations. United Nations. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- ^ a b «History of United Nations 1941 – 1950». United Nations. Archived from the original on 12 March 2015. Retrieved 12 March 2015.

- ^ «Queens Public Library Digital». digitalarchives.queenslibrary.org.

- ^ «United Nations, Queens: A Local History of the 1947 Israel-Palestine Partition». The Center for the Humanities.

- ^ Rosenthal, A. M. (19 May 1951). «U.N. Vacates Site at Lake Success; Peace Building Back to War Output». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 26 July 2022. Retrieved 26 July 2022.

- ^ Druckman, Bella (19 May 2021). «The United Nations Headquarters in Long Island’s Lake Success». Untapped New York.

- ^ «CBS television broadcast of a new series reporting the sessions and…» Getty Images.

- ^ (in French) «Genève renoue avec sa tradition de ville de paix», Le Temps, Thursday 16 January 2014.

- ^ «Research Guide: General Assembly». United Nations. Archived from the original on 21 October 2013.

- ^ «General Assembly of the United Nations». www.un.org.

- ^ General Assembly Adopts Work Programme for Sixty-Fourth Session, UN General Assembly Adopts Work Programme for Sixty-Fourth Session

- ^ UN Plenary Meetings of the 64th Session of the UN General Assembly, General Assembly of the UN

- ^ «Are UN resolutions binding? – Ask DAG!». ask.un.org. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- ^ «United Nations General Assembly». Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- ^ «Article 17 (1) of Charter of the United Nations». 17 June 2015.

- ^ «Articles 11 (2) and 11 (3) of Charter of the United Nations». 15 April 2016.

- ^ Population, total | Data | Table. World Bank. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- ^ UN Security Council : Resolutions, Presidential Statements, Meeting Records, SC Press Releases Archived 2 December 2012 at the Wayback Machine. United Nations. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- ^ United Nations Department of Management. United Nations. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- ^ a b c d «General Assembly of the United Nations». www.un.org. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ^ Statute of the International Court of Justice . San Francisco: United Nations. 26 June 1945 – via Wikisource.

- ^ United Nations (17 October 2019). «General Assembly Elects 14 Member States to Human Rights Council, Appoints New Under-Secretary-General for Internal Oversight Services». United Nations Meetings Coverage & Press Releases. United Nations. Retrieved 19 January 2020.

- ^ United Nations (4 June 2019). «Delegates Elect Permanent Representative of Nigeria President of Seventy-Fourth General Assembly by Acclamation, Also Choosing 20 Vice-Presidents». United Nations Meetings Coverage & Press Releases. United Nations. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- ^ «Members of the Court». International Court of Justice. n.d. Retrieved 19 January 2020.

- ^ a b Ruder, Nicole; Nakano, Kenji; Aeschlimann, Johann (2017). Aeschlimann, Johann; Regan, Mary (eds.). The GA Handbook: A practical guide to the United Nations General Assembly (PDF) (2nd ed.). New York: Permanent Mission of Switzerland to the United Nations. pp. 61–65. ISBN 978-0-615-49660-3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 November 2018.

- ^ United Nations General Assembly Session 33 E 138. Question of the composition of the relevant organs of the United Nations: amendments to rules 31 and 28 of the rules of procedure of the General Assembly to rules A/RES/33/138 19 December 1978. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

- ^ a b Winkelmann, Ingo (2010). Volger, Helmut (ed.). A Concise Encyclopedia of the United Nations (2nd ed.). Leiden: Martinus Nijhoff. pp. 592–96. ISBN 978-90-04-18004-8. S2CID 159105596.

- ^ «Ordinary sessions». United Nations General Assembly. United Nations. n.d. Retrieved 17 January 2020.

- ^ a b c Ruder, Nicole; Nakano, Kenji; Aeschlimann, Johann (2017). Aeschlimann, Johann; Regan, Mary (eds.). The GA Handbook: A practical guide to the United Nations General Assembly (PDF) (2nd ed.). New York: Permanent Mission of Switzerland to the United Nations. pp. 14–15. ISBN 978-0-615-49660-3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 November 2018.

- ^ Llenas, Bryan (4 January 2017). «Brazil’s President Rousseff to be First Woman to Open United Nations». Fox News. New York. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- ^ Manhire, Vanessa, ed. (2019). «United Nations Handbook 2019–20» (PDF). United Nations Handbook (Wellington, N.z.). (57th ed.). Wellington: Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade of New Zealand: 17. ISSN 0110-1951. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- ^ «What is the general debate of the General Assembly? What is the order of speakers at the general debate?». Dag Hammarskjöld Library. United Nations. 10 July 2019. Retrieved 17 January 2020.

- ^ «Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)». United Nations General Assembly. United Nations. n.d. Retrieved 17 January 2020.

- ^ Charter of the United Nations . San Francisco: United Nations. 26 June 1945 – via Wikisource.

- ^ «Special sessions». United Nations General Assembly. United Nations. n.d. Retrieved 17 January 2020.

- ^ «Emergency Special sessions». United Nations General Assembly. United Nations. n.d. Retrieved 17 January 2020.

- ^ United Nations General Assembly Session 5 Resolution 377. Uniting for Peace A/RES/377(V) 3 November 1950. Retrieved 17 January 2020.

- ^ a b «Main Committees». United Nations General Assembly. United Nations. Retrieved 19 June 2018.

- ^ «Subsidiary Organs of the General Assembly: Committees». United Nations General Assembly. United Nations. Retrieved 19 June 2018.

- ^ «Subsidiary Organs of the General Assembly: Commissions». United Nations General Assembly. United Nations. Retrieved 19 June 2018.

- ^ «Subsidiary Organs of the General Assembly: Boards». United Nations General Assembly. United Nations. Retrieved 19 June 2018.

- ^ «Subsidiary Organs of the General Assembly: Assemblies and Councils». United Nations General Assembly. United Nations. Retrieved 19 June 2018.

- ^ «Subsidiary Organs of the General Assembly: Working Groups». United Nations General Assembly. United Nations. Retrieved 19 June 2018.

- ^ The PGA Handbook: A practical guide to the United Nations General Assembly (PDF). Permanent Mission of Switzerland to the United Nations. 2011. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-615-49660-3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 November 2017. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- ^ «Report of the Secretary-General in Larger Freedom towards development, security and human rights for all».

- ^ «In Larger Freedom, Chapter 5». United Nations.

- ^ Johnstone, Ian (2008). «Legislation and Adjudication in the UN Security Council: Bringing down the Deliberative Deficit». American Journal of International Law. 102. No 2 (2): 275–308. doi:10.2307/30034539. JSTOR 30034539. S2CID 144268191.

- ^ Assembly, General. «Venezuela, Bolivarian Republic of H.E. Mr. Jorge Valero Briceño, Chairman of the Delegation». www.un.org.

- ^ «Revitalization of the Work of the General Assembly» (PDF). Globalpolicy.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 July 2009. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

- ^ «The Role of the UN General Assembly». Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

- ^ David Gelles (21 September 2017). «It’s the U.N.’s Week, but Executives Make It a High-Minded Mingle». The New York Times. Retrieved 22 September 2017.

External links[edit]

- United Nations General Assembly

- Webcast archive for the UN General Assembly

- Subsection of the overall UN webcast site

- Verbatim record of the 1st session of the UN General Assembly, Jan. 1946

- UN Democracy: hyper linked transcripts of the United Nations General Assembly and the Security Council

- UN General Assembly – Documentation Research Guide

- Council on Foreign Relations: The Role of the UN General Assembly

01:19 23.09.2023

(обновлено: 09:32 23.09.2023)

https://ria.ru/20230923/davlenie-1898148214.html

Лавров обсудил с главой ГА ООН деструктивность давления на страны

Лавров обсудил с главой ГА ООН деструктивность давления на страны — РИА Новости, 23.09.2023

Лавров обсудил с главой ГА ООН деструктивность давления на страны

Министр иностранных дел России Сергей Лавров на полях 78-й сессии Генассамблеи ООН обсудил с председателем ГА Дэннисом Фрэнсисом деструктивность давления на… РИА Новости, 23.09.2023

2023-09-23T01:19

2023-09-23T01:19

2023-09-23T09:32

россия

нью-йорк (город)

сергей лавров

оон

генеральная ассамблея оон

в мире

/html/head/meta[@name=’og:title’]/@content

/html/head/meta[@name=’og:description’]/@content

https://cdnn21.img.ria.ru/images/07e7/09/17/1898168789_200:507:2940:2048_1920x0_80_0_0_b52fe2b3251f33953337a7ad34260510.jpg

МОСКВА, 23 сен — РИА Новости. Министр иностранных дел России Сергей Лавров на полях 78-й сессии Генассамблеи ООН обсудил с председателем ГА Дэннисом Фрэнсисом деструктивность давления на страны на площадке организации, сообщает российский МИД. «Двадцать второго сентября в Нью-Йорке на полях недели высокого уровня 78-й сессии Генассамблеи ООН министр иностранных дел Российской Федерации Сергей Лавров провел встречу с избранным в июне председателем ГА Дэннисом Фрэнсисом… В ходе переговоров акцентирована важность поддержания в Генассамблее атмосферы конструктивного сотрудничества, а также неприемлемость привнесения в нее деструктивных инициатив конфронтационной природы, нацеленных на оказание давления на те или иные государства», — говорится в сообщении ведомства на сайте. Отмечается, что в ходе встречи министр и председатель выразили необходимость соблюдать закрепленный в Уставе ООН принцип «разделения труда» между ГА и другими главными органами. Лавров выразил надежду, что Фрэнсис будет «придерживаться сбалансированной и равноудаленной линии», а также учитывать мнение всех государств-членов, «не позволяя известной группе стран использовать площадку одного из уставных органов ООН в своих корыстных геополитических интересах», добавили в МИД.

https://ria.ru/20230912/oon-1895943770.html

россия

нью-йорк (город)

РИА Новости

internet-group@rian.ru

7 495 645-6601

ФГУП МИА «Россия сегодня»

https://xn--c1acbl2abdlkab1og.xn--p1ai/awards/

2023

РИА Новости

internet-group@rian.ru

7 495 645-6601

ФГУП МИА «Россия сегодня»

https://xn--c1acbl2abdlkab1og.xn--p1ai/awards/

Новости

ru-RU

https://ria.ru/docs/about/copyright.html

https://xn--c1acbl2abdlkab1og.xn--p1ai/

РИА Новости

internet-group@rian.ru

7 495 645-6601

ФГУП МИА «Россия сегодня»

https://xn--c1acbl2abdlkab1og.xn--p1ai/awards/

https://cdnn21.img.ria.ru/images/07e7/09/17/1898168789_171:0:2903:2048_1920x0_80_0_0_31a7e1184daee4db2105c40070ae9504.jpg

РИА Новости

internet-group@rian.ru

7 495 645-6601

ФГУП МИА «Россия сегодня»

https://xn--c1acbl2abdlkab1og.xn--p1ai/awards/

РИА Новости

internet-group@rian.ru

7 495 645-6601

ФГУП МИА «Россия сегодня»

https://xn--c1acbl2abdlkab1og.xn--p1ai/awards/

россия, нью-йорк (город), сергей лавров, оон, генеральная ассамблея оон, в мире

Россия, Нью-Йорк (город), Сергей Лавров, ООН, Генеральная Ассамблея ООН, В мире

Лавров обсудил с главой ГА ООН деструктивность давления на страны

Лавров и глава ГА ООН Фрэнсис обсудили деструктивность давления на страны

МОСКВА, 23 сен — РИА Новости. Министр иностранных дел России Сергей Лавров на полях 78-й сессии Генассамблеи ООН обсудил с председателем ГА Дэннисом Фрэнсисом деструктивность давления на страны на площадке организации, сообщает российский МИД.

«

«Двадцать второго сентября в Нью-Йорке на полях недели высокого уровня 78-й сессии Генассамблеи ООН министр иностранных дел Российской Федерации Сергей Лавров провел встречу с избранным в июне председателем ГА Дэннисом Фрэнсисом… В ходе переговоров акцентирована важность поддержания в Генассамблее атмосферы конструктивного сотрудничества, а также неприемлемость привнесения в нее деструктивных инициатив конфронтационной природы, нацеленных на оказание давления на те или иные государства», — говорится в сообщении ведомства на сайте.

Отмечается, что в ходе встречи министр и председатель выразили необходимость соблюдать закрепленный в Уставе ООН принцип «разделения труда» между ГА и другими главными органами.

Лавров выразил надежду, что Фрэнсис будет «придерживаться сбалансированной и равноудаленной линии», а также учитывать мнение всех государств-членов, «не позволяя известной группе стран использовать площадку одного из уставных органов ООН в своих корыстных геополитических интересах», добавили в МИД.

Зеленский раскритиковал ООН, заявив о недостаточном давлении на Россию

Генеральная Ассамблея ООН – главный директивный, совещательный и представительный орган Организации Объединенных Наций. Состав Ассамблеи формируется из представителей всех государств членов ООН. На сегодняшний день в состав Организации Объединенных Наций входят 193 государства, каждое из которых представлено своей делегацией на заседаниях Генеральной Ассамблеи. Сессии Ассамблеи проходят в штаб-квартире ООН в Нью-Йорке.

История создания Организации Объединенных Наций

Идея создания международной организации, главной задачей которой было поддержание мира и безопасности зародилась во время Второй мировой войны. Первым шагом к созданию ООН стало подписание Соединенными Штатами Америки и Великобритании документа, в котором были изложены основные принципы международной безопасности. Он был подписан 14 августа 1941 года президентом США Ф. Д. Рузвельтом и премьер-министром Великобритании У. Черчиллем на военно-морской базе Арджентия в Ньюфаундленде. Документ получил название Атлантической хартии.

Вскоре к Атлантической хартии присоединились 26 стран входящих в антигитлеровскую коалицию. 1 января 1942 года ими была подписана декларация Объединенных Наций, в которой выражалась поддержка основным пунктам хартии.

На московской конференции, проходившей с 19 по 30 октября 1943 года, представители СССР, США, Великобритании и Китая подписали декларацию, в которой призывали создать международную организацию, которая занималась решениями проблем мировой безопасности. Вопрос по созданию такой организации также поднимался на встрече руководителей стран-союзников 1 декабря 1943 года в Тегеране.

С 21 сентября по 7 октября 1944 года на заседаниях проходивших в Вашингтоне, дипломаты СССР, США, Великобритании и Китая договорились о структуре, целях и функциях новой организации. 11 февраля 1945 года на Ялтинской конференции Сталин, Черчилль и Рузвельт высказались о готовности создать «всеобщую международную организацию для поддержания мира и безопасности».

Итогом этой договоренности стала Конференция прошедшая в Сан-Франциско 25 апреля 1945 года. На этой конференции делегаты от 50 стран подготовили Устав новой организации. 24 октября 1945 года Устав ООН был ратифицирован странами – постоянными участниками Совета Безопасности (СССР, США, Великобритания, Китай, Франция) и таким образом была создана Организация Объединенных Наций.

Первое заседание Генеральной Ассамблеи ООН состоялось 10 января 1946 года в Центральном зале Вестминстерского дворца в Лондоне. На ней присутствовали делегации 51 государства. Первая резолюция Генеральной Ассамблеей была принята 24 января 1946 года. Она касалась мирного использования атомной энергии и ликвидации ядерного и другого оружия массового поражения.

Динамика увеличения стран-членов ООН

Структура Генеральной Ассамблеи ООН

Генеральная Ассамблея была учреждена в соответствии с Уставом Организации Объединенных Наций в 1945 году. Руководит Ассамблеей председатель, который выбирается голосованием. Также методом голосования выбирается 21 заместитель председателя. При голосовании каждое государство-участник ООН имеет 1 голос. Председатель и его заместители избираются на одну сессию и выполняют свои обязанности в течение той сессии на которой они были выбраны. Действующий председатель Генеральной Ассамблеи ООН – Сэм Кутеса (Уганда).

Каждая новая сессия Генеральной Ассамблеи ООН начинается с решения организационных вопросов, после чего начинаются общие прения. В ходе проведения общих прений представители всех государств имеющих членство в ООН получают возможность высказать свою позицию на тему международных вопросов. Как правило, общие прения проходят 7 дней, после чего Ассамблея переходит к решению вопросов стоящих на ее повестке. Поскольку вопросов, находящихся в рассмотрении Генеральной Ассамблеи ООН очень много, для оптимизации ее работы были созданы специальные комитеты. Комитеты разделены по тематике вопросов и занимаются непосредственным их обсуждением. После чего резолюции вынесенные комитетами рассматриваются на пленарных заседаниях Генеральной Ассамблеи ООН. На сегодняшний функционирует 6 главных комитетов:

- Первый комитет рассматривает вопросы посвященные разоружению и международной безопасности. Действующий председатель комитета — Кортни Рэттри (Ямайка);

- Второй комитет рассматривает вопросы касающиеся экономической и финансовой деятельности. Действующий председатель комитета – Себастьяно Карди (Италия);

- Третий комитет рассматривает вопросы связанные с социальными и гуманитарными проблемами, а также рассматривает вопросы культуры. Действующий председатель комитета – София Мескита Боргес (Тимор Лешти);

- Четвертый комитет занимается рассмотрением политических вопросов, которые не входят в юрисдикцию других комитетов. В их числе вопросы деколонизации и деятельности БАПОР (Ближневосточное агентство ООН для помощи палестинским беженцам и организации работ). Действующий председатель комитета – Дурга Прасад Бхаттараи (Непал);

- Пятый комитет рассматривает административные и бюджетные вопросы Организации Объединенных Наций. Действующий председатель комитета –Франтишек Ружечка (Словакия);

- Шестой комитет рассматривает вопросы международного права. Действующий председатель комитета – Тувако Натэниел Манонги (Танзания);

Помимо шести основных комитетов функционируют комитет по проверке полномочий и генеральный комитет. Комитет по проверке полномочий насчитывает 9 членов, назначаемых Генеральной Ассамблеей в задачу которых входит проверка полномочий представителей государств-членов ООН.

Генеральный комитет занимается организационными вопросами Ассамблеи. В его задачу входит оказывать содействие Председателю в составлении повестки дня для каждого пленарного заседания, устанавливать очередность рассматриваемых вопросов и координировать работу основных шести комитетов. Кроме этого, генеральный комитет предоставляет рекомендации по дате закрытия сессии Генеральной Ассамблеи. В состав комитета входит председатель, 21 его заместитель и руководители шести основных комитетов.

Кроме комитетов, действуют другие вспомогательные органы, решающие более узкий круг вопросов. Вспомогательные органы подразделяются на советы, комиссии и рабочие группы. Советы и комиссии делятся на исполнительные и консультационные. На сегодняшний день действуют Исполнительные совет Детского фонда ООН, Исполнительные совет Мировой продовольственной программы, Исполнительный совет Программы развития ООН в области народонаселения. К консультационным органам относятся Совет по вопросам разоружения и консультационная комиссия БАПОР. Кроме этого, в структуре Генеральной Ассамблеи функционируют:

- Комиссия международного права. Занимается вопросами прогрессивного развития международного права и его кодификацией;

- Комиссия ООН по праву международной торговли. Занимается вопросами содействия унификации права международной торговли;

- Комиссия по разоружению;

- Комиссия по международной гражданской службе. Занимается вопросами создания единой международной гражданской службы путем применения общих норм и методов в отношении персонала;

- Комиссия по миростроительству. Занимается вопросами предотвращения военных конфликтов;

- Комиссия ревизоров. Оказывает независимые аудиторские услуги.

Рабочие группы создаются Генеральной Ассамблеей в соответствии с принятыми резолюциями и решениями на пленарных заседаниях. Группы подразделяются на группы открытого состава и специальные рабочие группы. К группам отрытого состава относятся группы рассматривающие вопросы: защиты прав пожилых людей, финансового положения ООН, импорта и экспорта обычных видов вооружений и пр. Специальные рабочие группы занимаются вопросами: активизации деятельности Генеральной Ассамблеи, обеспечению мира в Африке, координации встреч на самом высоком уровне касающихся экономического развития государств и пр.

Задачи и функции Генеральной Ассамблеи

Генеральная Ассамблея ООН является наиболее представительным органом этой организации, так как в нее входят делегации всех стран-членов ООН. По своей сути Генеральная Ассамблея является консультационным международным органом. Ведь в отличие от резолюций Совета Безопасности ООН, резолюции Генеральной ассамблеи носят не обязательный, а рекомендательный характер.

Но в то же время, принятые Ассамблеей резолюции имеют большое морально-политическое значение для международных отношений. Нынешний генеральный секретарь ООН Пан Ги Мун заявил, что хотя резолюции Генеральной Ассамблеи не носят обязательный характер, ООН в своей работе будет руководствоваться их положениями.

Такое заявление Пан Ги Муна связано в первую очередь с тем, что на резолюцию Генеральной Ассамблеи не налагается вето. Это отличает резолюции ГА от резолюций Совета Безопасности ООН. Хотя решения СовБеза являются обязательными к выполнению для всех стран-участниц ООН, резолюция может быть принята только в том случае если ни один из постоянных участников Совета Безопасности не проголосовал «против». Резолюции Генеральной Ассамблеи принимаются при условии 50% большинства при голосовании. При рассмотрении особо важных вопросов, для принятия положительного решения, необходимо согласие 2/3 делегатов.

Генеральная Ассамблея ООН является форумом для обсуждения всех проблем международной политики прописанных в Уставе организации. Согласно действующего Устава, Генеральная Ассамблея призвана выполнять следующие функции:

- Обсуждение вопросов касающихся поддержания мира и безопасности, вопросов разоружения. Вынесение рекомендаций по этим вопросам;

- Обсуждение и вынесение рекомендаций по вопросам касающихся организации и Устава ООН.

- Организация исследований в областях международного права и международного сотрудничества в различных областях. Содействие осуществлению прав и свобод человека;

- Вынесение рекомендаций по мирному урегулированию конфликтов;

- Рассмотрение и утверждение бюджета ООН;

- Избрание и утверждение представителей в руководящие органы ООН.

Кроме этого, Генеральная Ассамблея ООН может принимать необходимые меры, в случае когда имеется угроза безопасности мира, а Совет Безопасности ООН не может принять решение из-за его ветирования одним из своих постоянных членов. Это прописано в резолюции «Единство в пользу мира» от 3 ноября 1950 года.

Порядок работы Генеральной Ассамблеи

Генеральная Ассамблея ООН является сессионным органом. Сессии бывают ежегодные очередные и внеочередные специальные. Очередные сессии Генеральной Ассамблеи начинаются в третий вторник сентября. При этом Генеральный секретарь извещает всех участников, как минимум за 60 дней до начала заседаний. Также Генеральным секретарем составляется предварительная повестка дня очередной сессии и любая из стран-участниц имеют право не менее чем за 30 дней до открытия сессии внести на рассмотрение дополнительные пункты.

На первом заседании в обязательном порядке проводятся выборы Председателя Генеральной Ассамблеи ООН, его заместителей, глав шести основных комитетов, а также оговаривается дата закрытия сессии.

Внеочередные сессии Ассамблеи созываются Генеральным Секретарем ООН по требованию Совета Безопасности или в случае получения от большинства членов ООН уведомлений о созыве такой сессии. Направить уведомление о созыве внеочередной сессии может любой член ООН, а Генеральный Секретарь обязан известить других участников. Сессия созывается, если в течение 30 дней большинство участников дадут свое согласие на проведение заседаний.

https://inosmi.ru/20230923/oon-265776267.html

В США назвали «главного болвана» Генассамблеи ООН. И это не Зеленский

В США назвали «главного болвана» Генассамблеи ООН. И это не Зеленский

В США назвали «главного болвана» Генассамблеи ООН. И это не Зеленский

Несмотря на то, что во время заседания Генассамблеи ООН Байден выставил себя идиотом, а Зеленский – подхалимом, приз за глупость достается президенту Колумбии… | 23.09.2023, ИноСМИ

2023-09-23T00:45

2023-09-23T00:45

2023-09-23T00:45

american thinker

политика

джо байден

владимир зеленский

колумбия

/html/head/meta[@name=’og:title’]/@content

/html/head/meta[@name=’og:description’]/@content

https://cdnn1.inosmi.ru/img/07e6/0b/14/258032205_0:160:3073:1888_1920x0_80_0_0_ec7a6debb48459e20459f400d0b8bfd0.jpg

Из-за слабости руководства Соединенных Штатов сессия Генеральной Ассамблеи ООН в этом году проходит хуже, чем обычно.Конечно же, со своей стороны, Джо Байден постарался выставить себя идиотом, когда принялся расхваливать лидерство Организации Объединенных Наций – не Америки, – которое позволило вывести миллиард человек из нищеты и тому подобное.Читайте ИноСМИ в нашем канале в TelegramНе отставал от него и Владимир Зеленский, который, попросив мировое сообщество предоставить его стране военную помощь и иную поддержку, заявил, что наиболее остро стоящей мировой проблемой является глобальное потепление.Каков подхалим!Но главный приз за глупость достается ультраправому и антиамерикански настроенному президенту Колумбии Густаво Петро (Gustavo Petro) – близкому союзнику покойного и никем не оплакиваемого Уго Чавеса. Он пригрозил отправить еще больше нелегалов в Соединенные Штаты – в страну, которую он без тени иронии сравнил с нацистской Германией. Затем он сурово отчитал США, предъявив им сразу несколько ложных обвинений в отношении того, как Америка обращается с нелегалами, на всякий случай приплетя к этому еще и тему расы.Он был похож на грубую сатирическую пародию на какого-нибудь номинального интеллектуала от движения «смятения и негодования» в странах третьего мира, которая сошла к нам прямо со страниц книг В.С. Найпола (V.S. Naipaul).Вот что пишет по этому поводу издание Washington Examiner:»Президент Колумбии Густаво Петро спрогнозировал, что „миллиарды людей уклонятся от службы в армиях” и мигрируют в Соединенные Штаты и другие западные демократии, которые он ранее сравнил с нацистской Германией.„Миллиарды людей уклонятся от службы в армиях и для этого меняют страны проживания, – заявил Петро на Генассамблее ООН. – Отток населения через границы усилился. Они натравливают на иммигрантов собак. Они сажают людей на лошадей и дают им в руки кнуты, палки и цепи, чтобы те преследовали [иммигрантов]. Они построили тюрьмы”».Кнуты? Нацисты? Неужели, с вашей точки зрения, Гус, это объясняет, почему иммигранты продолжают ехать в Америку?А потом номинальный союзник Соединенных Штатов и получатель многомиллионной американской помощи решил вытащить еще и расовую карту:»Они даже построили тюрьмы в море, чтобы эти женщины и мужчины не смогли ступить на землю белых людей, которые до сих пор считают себя высшей расой, – сказал Петро во вторник. – Они питают ностальгию по прежним временам, и своими решениями и выборами они возрождают лидера, который так говорил и в результате убил миллионы людей».Когда мы вообще успели перейти на эту тему?Все началось со лжи о том, что Соединенные Штаты охраняют свою границу и стараются не допустить мигрантов на свою территорию.О чем он вообще говорит?Администрация Байдена придерживается тактики «поймал-отпустил», в результате чего в страну попадают все, кто туда приезжает. Сейчас число прибывающих в Соединенные Штаты является одним из самых высоких за всю историю. За время президентства Байдена в Америку пустили около шести миллионов нелегалов. Аргумент Петро о том, что пограничники применяют «кнуты» в отношении мигрантов – это еще более чудовищная ложь. Даже издание Politico сообщило об этом более года назад. Однако Петро все равно повторил это заявление под запись, решив тем самым подстегнуть тех, кто тоже питает антипатию к Америке, – хотя при этом он продолжает призывать людей въезжать в Соединенные Штаты нелегальным образом.Кто там говорил, что волна нелегалов, пересекающих границу, – это не вторжение? Заявления Петро доказывают, что именно вторжением она и является, и он хочет, чтобы волна стала больше, поскольку он хорошо знает, – бесконтрольная нелегальная иммиграция – это отличный способ уничтожить суверенитет страны. Сидя у себя в Колумбии, этот ультралевый социалист и бывший партизан-террорист теперь подначивает нелегалов.Его упоминание о расовых предрассудках тоже прозвучало довольно странно с учетом того, что у него абсолютно белая кожа, голубые глаза, а Википедия утверждает, что его предки были выходцами из Италии. Этот человек является одним из тех белых людей, о которых он нас предупреждает. А еще он представитель изнеженной элиты.Каков лицемер!Однако широкая картина вызывает еще больше тревоги. Своим выступлением Петро ясно продемонстрировал, что перемещения мигрантов – это спланированный процесс и что за пределами границ Соединенных Штатов социалисты, подобные ему, активно этим пользуются. Кто-нибудь обсуждает эту тему здесь, в Америке? Нет, потому что мы, должно быть, ошибочно полагаем, что это всего лишь мигранты, а вовсе не организованное завоевание. Вместо того чтобы постыдиться, что его собственная страна отправила в Америку огромное число нелегалов, которые пойдут на все, лишь бы не вернуться обратно в Колумбию, Петро открыто радуется их притоку и называет это победой темнокожих людей над белыми. При этом он совершенно игнорирует мнение жителей во многом латиноамериканского штата Техас, где последствия этого притока ощущаются острее всего. Он рассматривает приток мигрантов как свою «победу».Разумеется, если только Соединенные Штаты не заплатят ему за глобальное потепление.Ему очень хотелось бы получить эти деньги на создание зеленой экономики, учитывая, что он уже уничтожил ведущую экспортоориентированную отрасль Колумбии, а именно нефтедобычу, во имя охраны окружающей среды. Место нефтяных вышек заняли вовсе не ветряные генераторы, а кокаин – это же Колумбия.Просто потрясающе, как эти страны начинают наглеть, когда чувствуют слабость руководства Соединенных Штатов. Петро отлично знал, что США ему не ответят – и, конечно же, они не ответили: их представители просто сидели и делали вид, что все в порядке. Соединенные Штаты должны были указать, что с момента прихода Петро к власти жизнь в Колумбии стала очень тяжелой, в результате чего показатели миграции подскочили практически с нуля при президенте Альваро Урибе до десятков тысяч колумбийцев, которые теперь бегут от социализма в его стране.Но было бы слишком требовать такого от Джо Байдена, поэтому Петро открыто наносит удар по стране, которую он ненавидит, записывая себе в заслугу то, что толпы людей пытаются бежать из Колумбии и любыми способами попасть в Соединенные Штаты.Автор статьи: Моника Шоуолтер (Monica Showalter)

/20230922/oon-265772395.html

/20230907/bayden-265540064.html

колумбия

ИноСМИ

info@inosmi.ru

+7 495 645 66 01

ФГУП МИА «Россия сегодня»

2023

ИноСМИ

info@inosmi.ru

+7 495 645 66 01

ФГУП МИА «Россия сегодня»

Новости

ru-RU

https://inosmi.ru/docs/about/copyright.html

https://xn--c1acbl2abdlkab1og.xn--p1ai/

ИноСМИ

info@inosmi.ru

+7 495 645 66 01

ФГУП МИА «Россия сегодня»

https://cdnn1.inosmi.ru/img/07e6/0b/14/258032205_170:0:2901:2048_1920x0_80_0_0_46d86a54559b45332125a89d53679678.jpg

ИноСМИ

info@inosmi.ru

+7 495 645 66 01

ФГУП МИА «Россия сегодня»

american thinker, политика, джо байден, владимир зеленский, колумбия

Материалы ИноСМИ содержат оценки исключительно зарубежных СМИ и не отражают позицию редакции ИноСМИ

Несмотря на то, что во время заседания Генассамблеи ООН Байден выставил себя идиотом, а Зеленский – подхалимом, приз за глупость достается президенту Колумбии Густаво Петро, пишет AT. Он проявил завидное лицемерие в том, что касается «завоевания США», подчеркивает автор статьи.

Из-за слабости руководства Соединенных Штатов сессия Генеральной Ассамблеи ООН в этом году проходит хуже, чем обычно.

Конечно же, со своей стороны, Джо Байден постарался выставить себя идиотом, когда принялся расхваливать лидерство Организации Объединенных Наций – не Америки, – которое позволило вывести миллиард человек из нищеты и тому подобное.

Не отставал от него и Владимир Зеленский, который, попросив мировое сообщество предоставить его стране военную помощь и иную поддержку, заявил, что наиболее остро стоящей мировой проблемой является глобальное потепление.

Но главный приз за глупость достается ультраправому и антиамерикански настроенному президенту Колумбии Густаво Петро (Gustavo Petro) – близкому союзнику покойного и никем не оплакиваемого Уго Чавеса. Он пригрозил отправить еще больше нелегалов в Соединенные Штаты – в страну, которую он без тени иронии сравнил с нацистской Германией. Затем он сурово отчитал США, предъявив им сразу несколько ложных обвинений в отношении того, как Америка обращается с нелегалами, на всякий случай приплетя к этому еще и тему расы.

Он был похож на грубую сатирическую пародию на какого-нибудь номинального интеллектуала от движения «смятения и негодования» в странах третьего мира, которая сошла к нам прямо со страниц книг В.С. Найпола (V.S. Naipaul).

Вот что пишет по этому поводу издание Washington Examiner:

«Президент Колумбии Густаво Петро спрогнозировал, что „миллиарды людей уклонятся от службы в армиях” и мигрируют в Соединенные Штаты и другие западные демократии, которые он ранее сравнил с нацистской Германией.

„Миллиарды людей уклонятся от службы в армиях и для этого меняют страны проживания, – заявил Петро на Генассамблее ООН. – Отток населения через границы усилился. Они натравливают на иммигрантов собак. Они сажают людей на лошадей и дают им в руки кнуты, палки и цепи, чтобы те преследовали [иммигрантов]. Они построили тюрьмы”».

Кнуты? Нацисты? Неужели, с вашей точки зрения, Гус, это объясняет, почему иммигранты продолжают ехать в Америку?

А потом номинальный союзник Соединенных Штатов и получатель многомиллионной американской помощи решил вытащить еще и расовую карту:

«Они даже построили тюрьмы в море, чтобы эти женщины и мужчины не смогли ступить на землю белых людей, которые до сих пор считают себя высшей расой, – сказал Петро во вторник. – Они питают ностальгию по прежним временам, и своими решениями и выборами они возрождают лидера, который так говорил и в результате убил миллионы людей».

Когда мы вообще успели перейти на эту тему?

Все началось со лжи о том, что Соединенные Штаты охраняют свою границу и стараются не допустить мигрантов на свою территорию.

Администрация Байдена придерживается тактики «поймал-отпустил», в результате чего в страну попадают все, кто туда приезжает. Сейчас число прибывающих в Соединенные Штаты является одним из самых высоких за всю историю. За время президентства Байдена в Америку пустили около шести миллионов нелегалов. Аргумент Петро о том, что пограничники применяют «кнуты» в отношении мигрантов – это еще более чудовищная ложь. Даже издание Politico сообщило об этом более года назад. Однако Петро все равно повторил это заявление под запись, решив тем самым подстегнуть тех, кто тоже питает антипатию к Америке, – хотя при этом он продолжает призывать людей въезжать в Соединенные Штаты нелегальным образом.

Кто там говорил, что волна нелегалов, пересекающих границу, – это не вторжение? Заявления Петро доказывают, что именно вторжением она и является, и он хочет, чтобы волна стала больше, поскольку он хорошо знает, – бесконтрольная нелегальная иммиграция – это отличный способ уничтожить суверенитет страны. Сидя у себя в Колумбии, этот ультралевый социалист и бывший партизан-террорист теперь подначивает нелегалов.

Его упоминание о расовых предрассудках тоже прозвучало довольно странно с учетом того, что у него абсолютно белая кожа, голубые глаза, а Википедия утверждает, что его предки были выходцами из Италии. Этот человек является одним из тех белых людей, о которых он нас предупреждает. А еще он представитель изнеженной элиты.

Однако широкая картина вызывает еще больше тревоги. Своим выступлением Петро ясно продемонстрировал, что перемещения мигрантов – это спланированный процесс и что за пределами границ Соединенных Штатов социалисты, подобные ему, активно этим пользуются. Кто-нибудь обсуждает эту тему здесь, в Америке? Нет, потому что мы, должно быть, ошибочно полагаем, что это всего лишь мигранты, а вовсе не организованное завоевание. Вместо того чтобы постыдиться, что его собственная страна отправила в Америку огромное число нелегалов, которые пойдут на все, лишь бы не вернуться обратно в Колумбию, Петро открыто радуется их притоку и называет это победой темнокожих людей над белыми. При этом он совершенно игнорирует мнение жителей во многом латиноамериканского штата Техас, где последствия этого притока ощущаются острее всего. Он рассматривает приток мигрантов как свою «победу».

Разумеется, если только Соединенные Штаты не заплатят ему за глобальное потепление.

Ему очень хотелось бы получить эти деньги на создание зеленой экономики, учитывая, что он уже уничтожил ведущую экспортоориентированную отрасль Колумбии, а именно нефтедобычу, во имя охраны окружающей среды. Место нефтяных вышек заняли вовсе не ветряные генераторы, а кокаин – это же Колумбия.

Просто потрясающе, как эти страны начинают наглеть, когда чувствуют слабость руководства Соединенных Штатов. Петро отлично знал, что США ему не ответят – и, конечно же, они не ответили: их представители просто сидели и делали вид, что все в порядке. Соединенные Штаты должны были указать, что с момента прихода Петро к власти жизнь в Колумбии стала очень тяжелой, в результате чего показатели миграции подскочили практически с нуля при президенте Альваро Урибе до десятков тысяч колумбийцев, которые теперь бегут от социализма в его стране.

Но было бы слишком требовать такого от Джо Байдена, поэтому Петро открыто наносит удар по стране, которую он ненавидит, записывая себе в заслугу то, что толпы людей пытаются бежать из Колумбии и любыми способами попасть в Соединенные Штаты.

Автор статьи: Моника Шоуолтер (Monica Showalter)